“In our time of environmental disaster and urgent demands for social justice, we need to acknowledge our senses and talk about our feelings.”

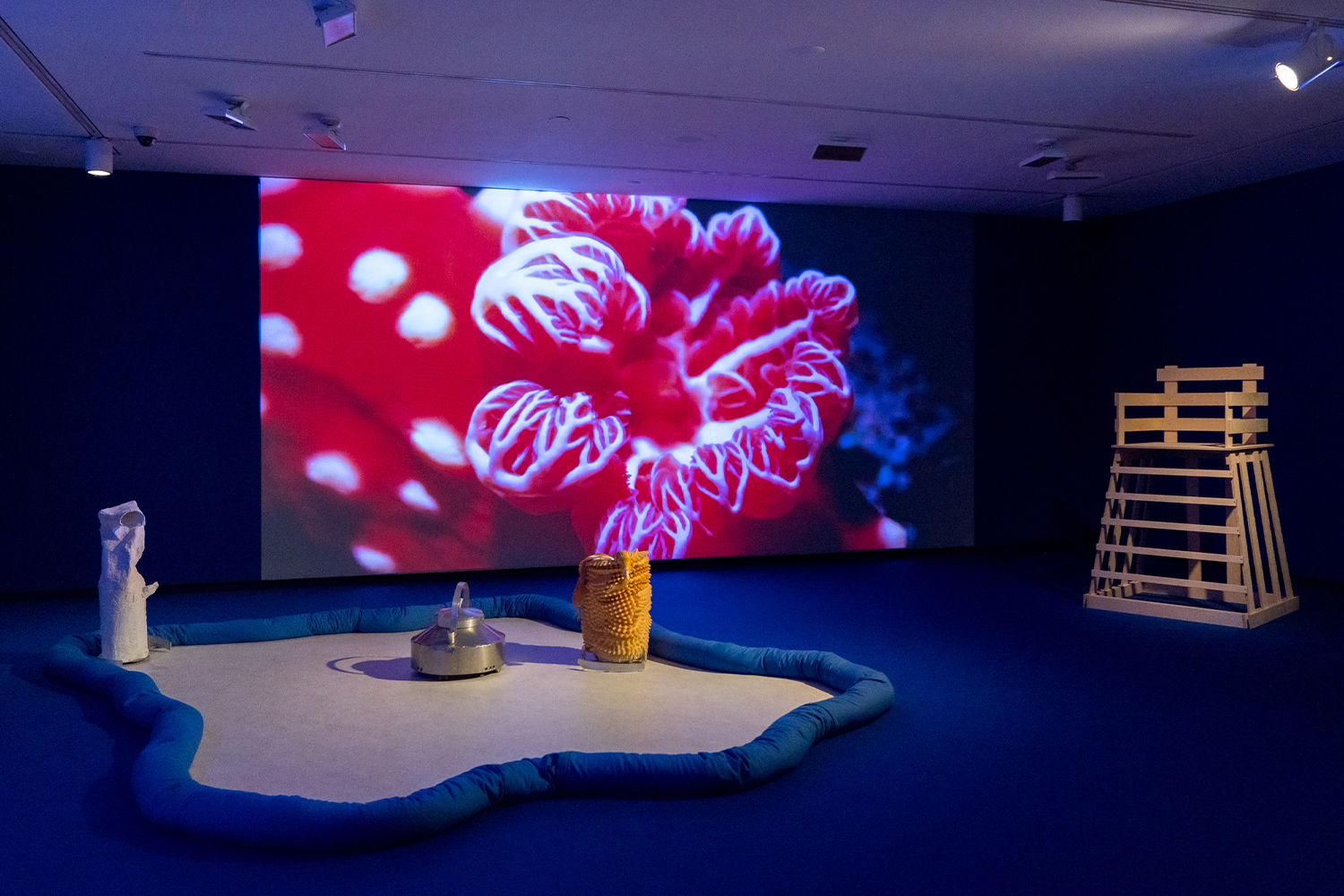

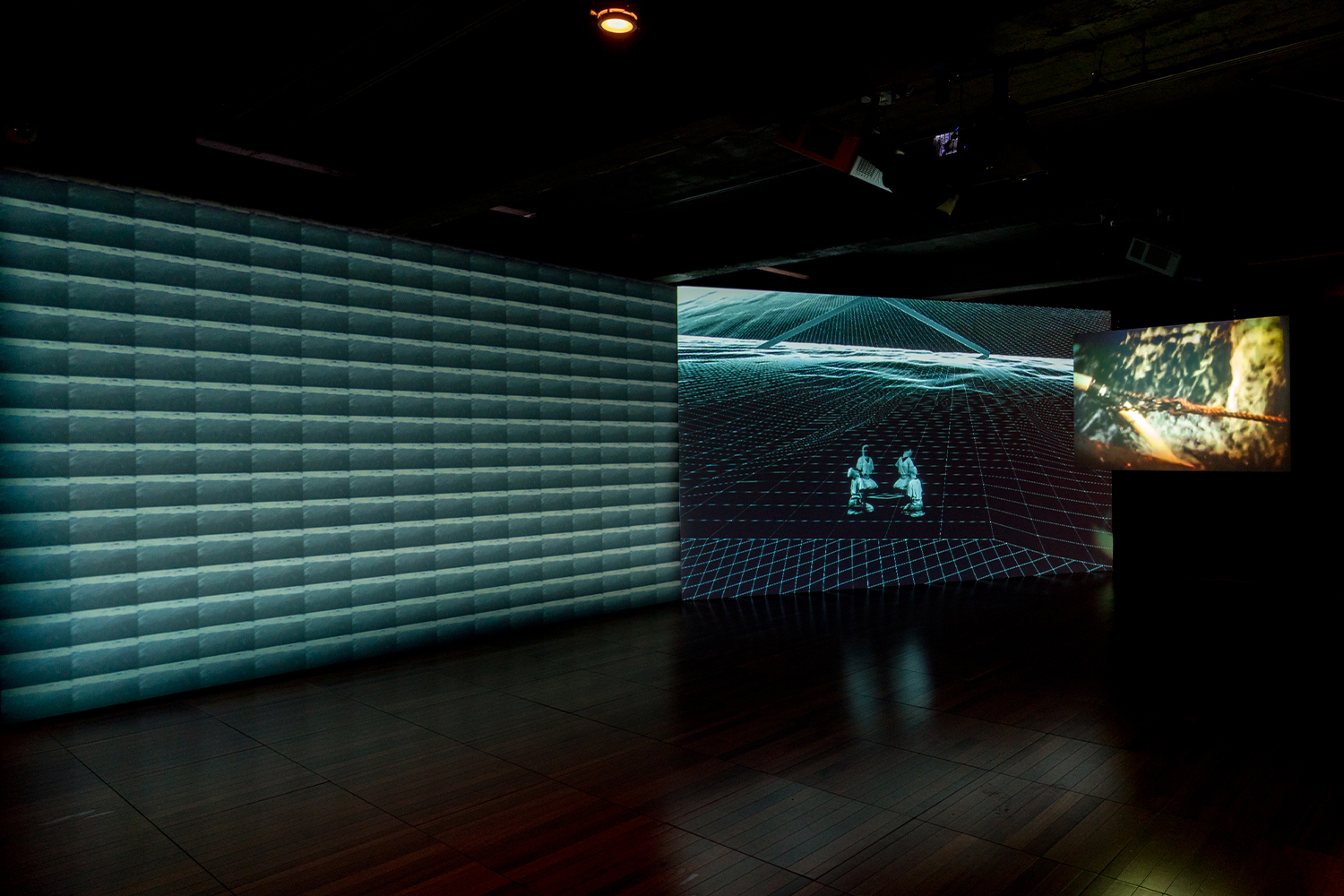

In Stefanie Hessler’s expanded curatorial text, she opens with the mise-en-scène of her eating a juicy blueberry — so many, in fact, that her hands drip with their juices. Following recent trends in social and environmental justice oriented toward the somatic, embodied, and transformative, Hessler inverts the Western valuation of analytical and critical thought to foreground feeling, sensing, and care. Evoking both duration and the privilege of immersion, the implications of hands so immersed in the eating of blueberries that they become saturated is a useful image for thinking through the series of exhibitions, texts, workshops, and special projects that make up “Sensing Nature.” Within the biennial, duration and immersion are qualities created through the predominance of video and installation and the sheer volume of exhibitions and projects.

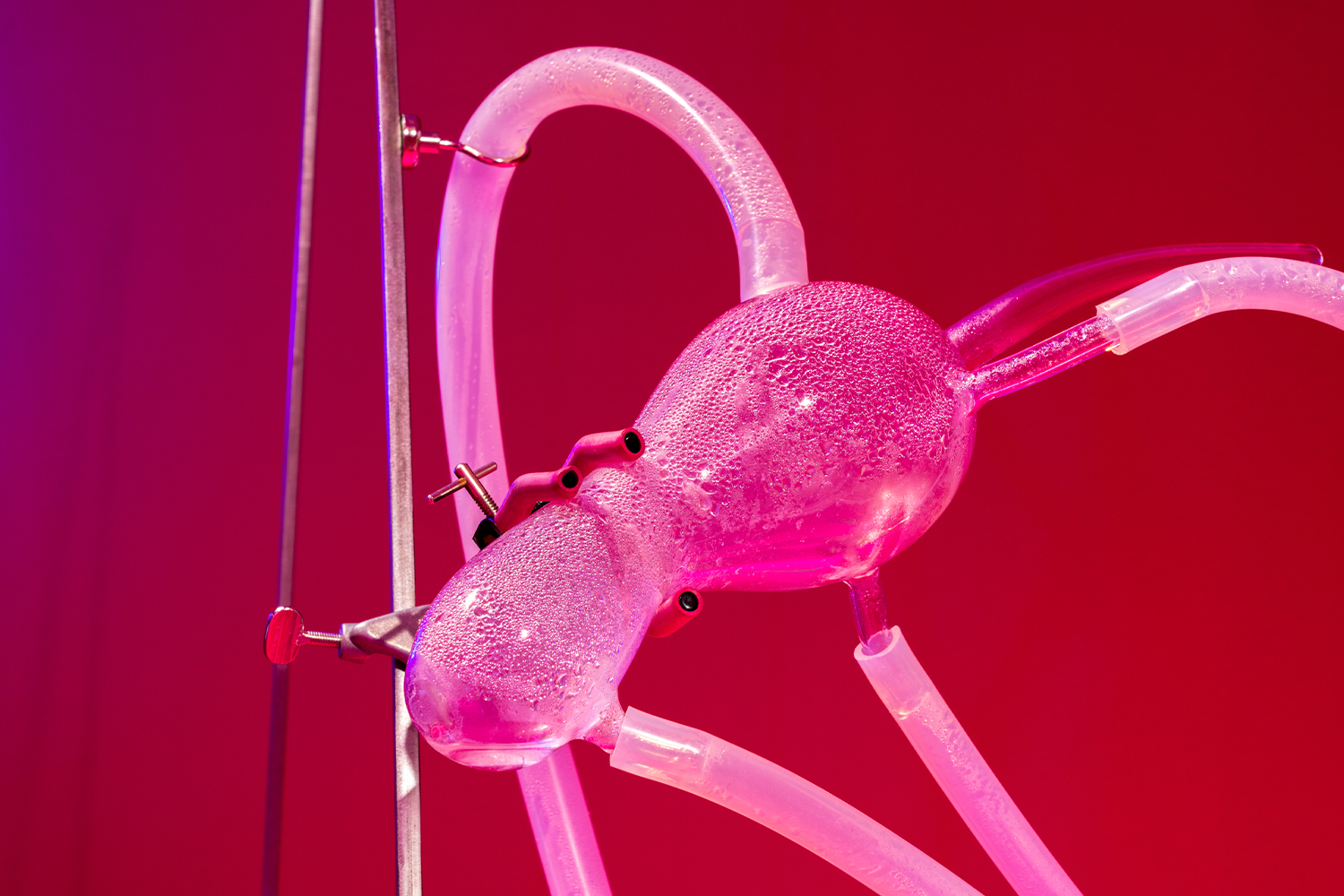

Reflective of the theoretical and spiritual underpinnings of “Sensing Nature” is Hessler’s suggestion that the blueberry can be an active participant in the experience of being eaten. This mirrors the centering of reciprocity between humans and nature, and is registered as a felt sense, a kind of undulating frequency between the artists and their subjects, collaborators, and curators. This quality is verified in the methodology and orientation of the Biennale, which acts as an invitation into a series of well-established sets of relations, visible in both the rhizomatic curatorial approach — initiated by Hessler, but clearly built in tandem with her primary collaborators, Camille Georgeson-Usher, Himali Singh Soin, and Maude Johnson — as well as in the artists’ mannerisms and tendencies. Here exhibitions are built on exchanges of letters, soundscapes, sketches, and photos (Laura Ortman and Caroline Monnet, From My Home to Yours, 2021); dogs and children who are named as collaborators (BUSH gallery’s “Diffracting: Of Light and of Land” 2021); and new habitats developed for local insects and Indigenous communities (T’uy’t’tanat-Cease Wyss, TEIONHENKWEN Supporters of Life, 2021).

Last night I spoke to Camille, who is a close friend and collaborator. We mused over the term “sensing” and how there is a kind of distance or intangibility built into it: Does it have depth or just hit the surface? What does it mean to be in relationship with nature, to be of it, as Hessler suggests, while simultaneously respecting it as an “enigmatic, active Other,”1 existing, as artist Abbas Akhavan proposes, “beyond our desires”?2 Unlike smell, sight, touch, or hearing, sensing evokes that which is imperceptible to physical ways of knowing. As Camille pointed out, we sense danger, for example. Sensing requires us to be slower, more attuned. It is work. Hard work. And worth it. From the brief time I have been involved in somatic practices as a trauma-informed healing modality, what I understand is that we need to become attuned to our nervous systems, that our nervous systems are like portals that hold all the wisdom and trauma of our ancestors, that the more able we are to regulate and tap into the power of our systems, the more we can create balance and connection through how we co-regulate with others. Also relevant to this context is to learn how to grow our capacities for holding pleasure as much as holding pain, grief, and despair.

Hessler’s call to “acknowledge our senses and talk about our feelings” is a call to being more integrated in our approach to major climate uncertainty, to centering the sociopolitical and relational. Collaboration means knowing who we are, where we come from, and what informs our subject position, so that we can be in right relation with those around us;3 it is to be clear and humble enough to know where to let go, how to learn without being extractive, how to get close without crushing.

If “Sensing Nature” is at once a set of exhibitions, texts, performances, workshops, and dialogues, it is also, perhaps more importantly, a framework for another way of being together in the face of our uncertain futures that might allow us, as Camille writes, “to imagine, even briefly, that we live somewhere built in tenderness and respect between all beings.”4