Kraftwerk Berlin is an astounding structural site, made up of a cavernous interior enclosed by an intricate layout for the distribution of electrical power. Until 1997, the once fully functioning power plant generated heat for the eastern sector of Berlin’s streets and housing blocks. Following its completion in the early 1960s, around the same time as the Berlin Wall, it became a GDR architectural landmark.

Prior to the ongoing and sometimes wavering pandemic restrictions, I would frequent the sectioned-off parts of this nightclub locus, either going to parties in the former battery room, now known as the cozy and intimate nightclub Ohm, or in the building’s basement that houses the well-known mega club Tresor. The latter was founded shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, marking the early developments of the city’s metamorphosis — an underground clubbing revolution while the fractured city tried to piece itself together again. Before the opening of this legendary club, Berlin Atonal — the annual sound art and music festival — took place between 1982 and 1990 in West Berlin’s Kreuzberg neighborhood. In 2013, Atonal relocated to Kraftwerk, just over a kilometer away from its original site in Kreuzberg. During Atonal’s first edition the power plant would have been impossible to reach because of the Wall dividing the city into East and West localities.

In response to the mandatory and necessary break from such all-night excursions throughout Berlin, the sonically attuned Atonal festival conceptualized “Metabolic Rift,” this year’s exhibition and concert series that began in late September and will continue throughout October, taking residence once again at Kraftwerk.

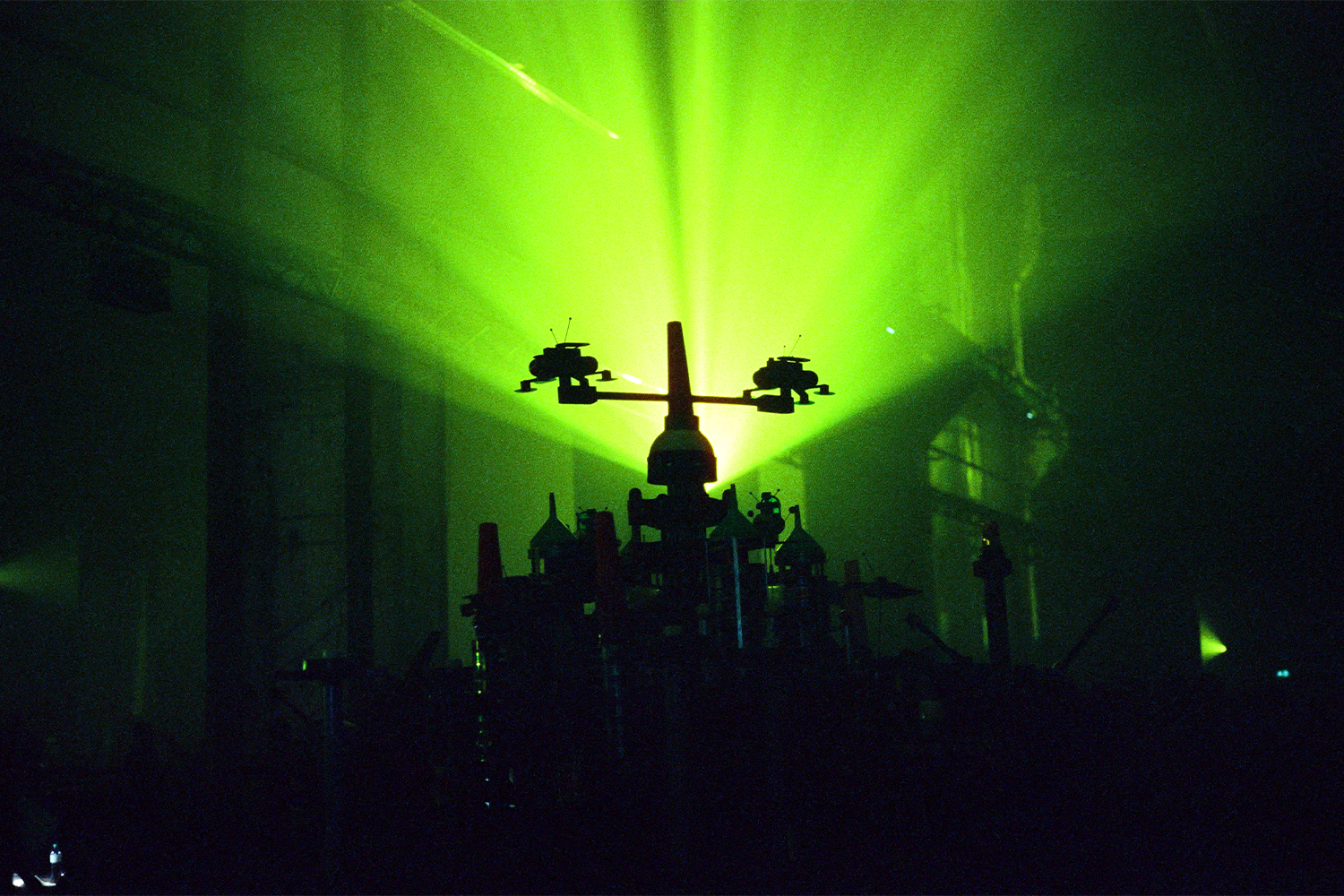

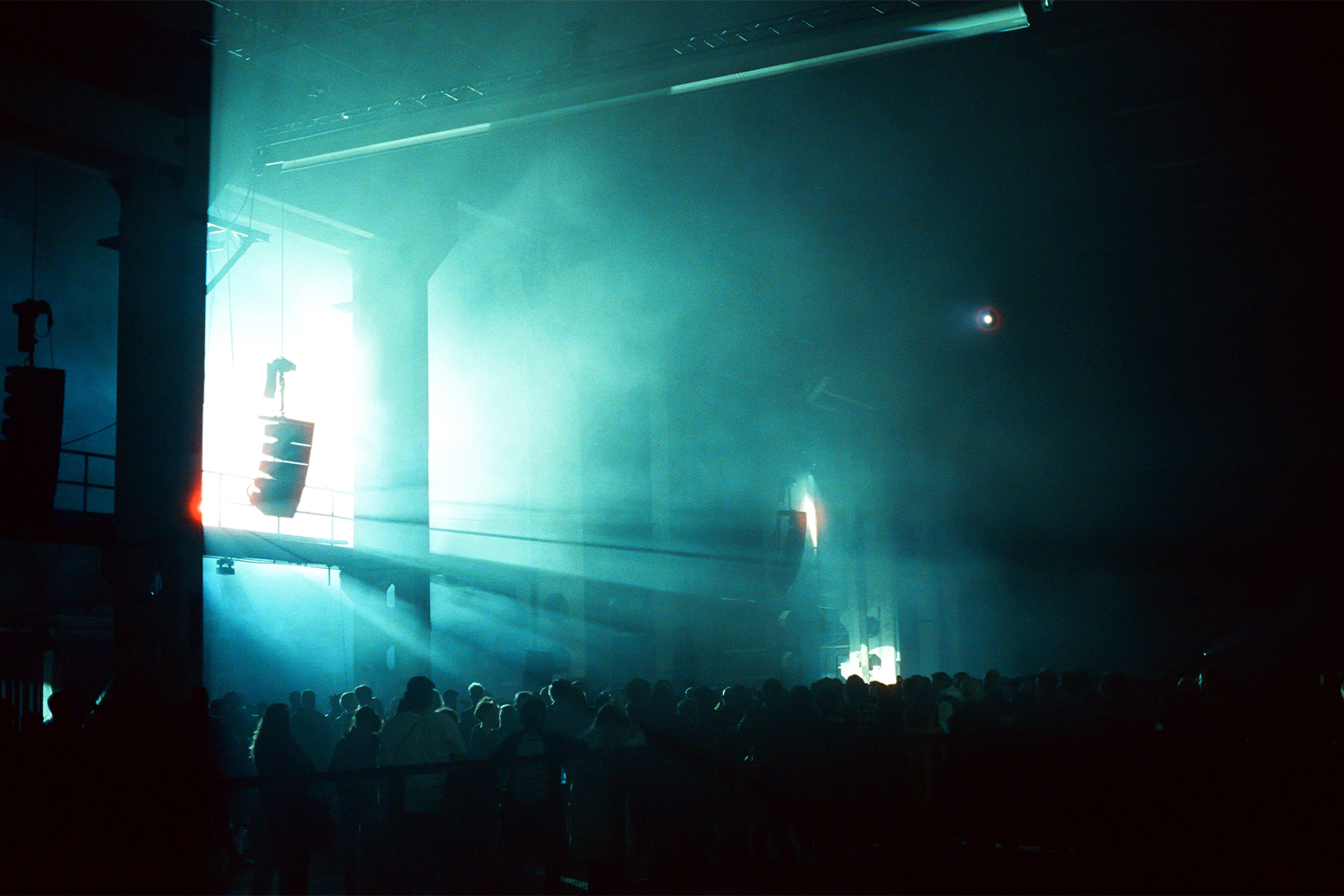

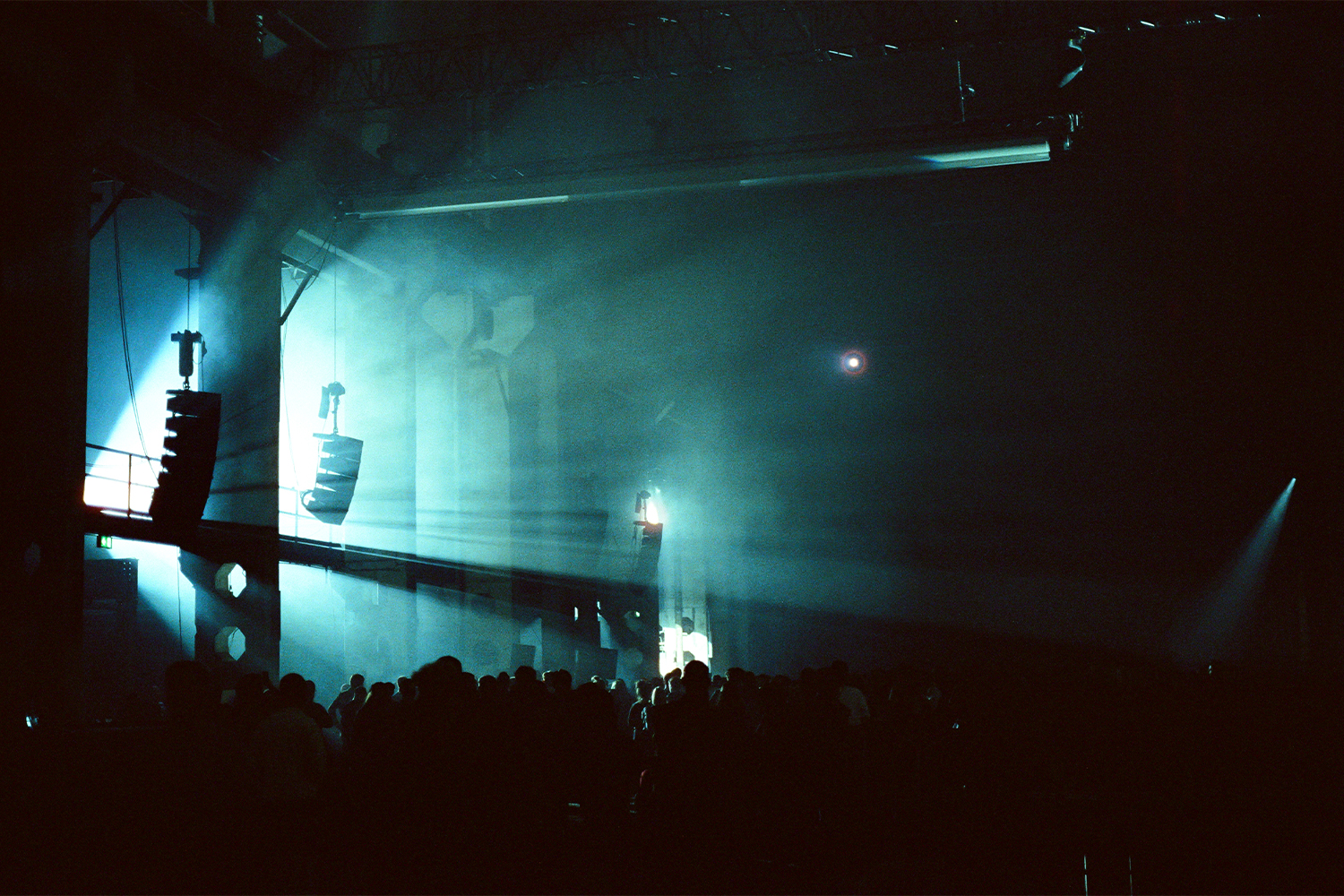

As a continuum for “an intensely concentrated and collective sensory experience” throughout the years, Atonal has dissipated sonic and visual elements in collaboration with and by commissioning artists and experimental musicians to activate the power station, overtaking the structure in its entirety. After last year’s hiatus, this year’s iteration takes a different approach as a departure from their antecedent five-day audio and visual spectacle, held primarily in the site’s impressive metal-and-concrete main hall.

Intended for smaller visitor clusters, “Metabolic Rift” takes the course of an unfolding — in which audiences follow choreographic “moving through” sequences within the lesser-known pathways and inner workings of the power plant. Whereas the works for the duration of the exhibition make themselves known in timed successions, the distinctive feature of this edition is described by the curators as a representation of a “metabolic system” — a system indicating some undisclosed living organism and all of its connected assemblages. What that entails for this contextual industrial setting is the various conjectures amassed by affect, sensing, and sound histories.

In recalling my participation in (or encounter with) Atonal’s “Metabolic Rift,” it’s crucial to acknowledge the works set within their intended “ghost-train” renditions, or, more accurately, the linear progression that guided my designated cluster.

We entered the building in tow, which brought to mind a very familiar experience of waiting just under Tresor’s red light entrance sign and doors. The cluster was advised to stick together and try not to fall behind. This suddenly made me aware of the stark contrast from a familiar experience aforementioned, of waiting to enter a club followed by drifting around, getting lost beyond measure, and wandering about until dawn — a clubbing experience I became accustomed to from bygone nights spent at Tresor. At this moment, under these controlled circumstances, this is not possible.

That awareness, however, quickly shifted as we descended into the vacant nightclub. We were met with artist and composer Pan Daijing’s binaural sound work with her accompanying multi-channel video installation titled SEAL (2021). The repetitive and arcane incantations throughout the track emulate a rapid downward plummet, while video footage of a body exuding moisture plays on the monitor and a corresponding spotlit melting ice block is positioned on the floor of what was once Tresor’s dance floor. A smoky vapor rises from the ground and fills the space to stage a claustrophobic cascade further into Daijing’s “psychoacoustic space and the transformations of energy.” Soon after doors open to depart from this space, the work cuts out and we are left with sustained physical or mental remnants activated by the fleeting moment of what just transpired. And by mandate, we proceed further down into the building. At this point, I’m overcome by a feeling of reluctance yet equally dazzled by the high-fidelity reproduction of descent, steering ahead into the underground maze of Kraftwerk.

Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste’s Devo (Listenin’ Out The Top Of Ya Head), (2021) is a sudden, ecstatic, abrasive clamor that quickly interrupted Daijing’s daze-like influence. The sound of pots and pans penetrated my stunned state. Toussaint-Baptiste’s sonic mediations confront how one looks at or spectates a work, the artist, and the socio-structural associations set firmly and deeply into the activity of listening — what is encountered when heard. An arrangement of cast-iron pots resonated clanging scales through bass transducers powered by amplifiers. Imparted by Toussaint-Baptiste’s multidisciplinary exploration into the subjective, this sonorous exploration affects sentience borne out “of the material history of bodies-as-property in the United States […] rooted into objects and places.” Toussaint-Baptiste’s Devo is composed after Russian composer and pianist Alexander Scriabin’s work with the “mystic chord,” a six-note harmonic scale driven by the spiritual underpinnings in Scriabin’s work. Scriabin wanted “to afford instant apprehension of — that is, to reveal — what was in essence beyond the mind of man to conceptualize. Its preternatural stillness was a gnostic intimation of a hidden otherness,” as Toussaint-Baptiste cites. Here the artist composed and assembled iron pots to resonate at Scriabin’s mystic chord frequencies, using dissonant sonorities to evoke and suggest images as a eulogy for the radical subversive tactics that enslaved people regularly employed for survival from the violence inflicted upon them by being situated in US southern states. Their use of cast iron pots was to conceal themselves and sidestep detection of their private assemblies prohibited by white slave owners.

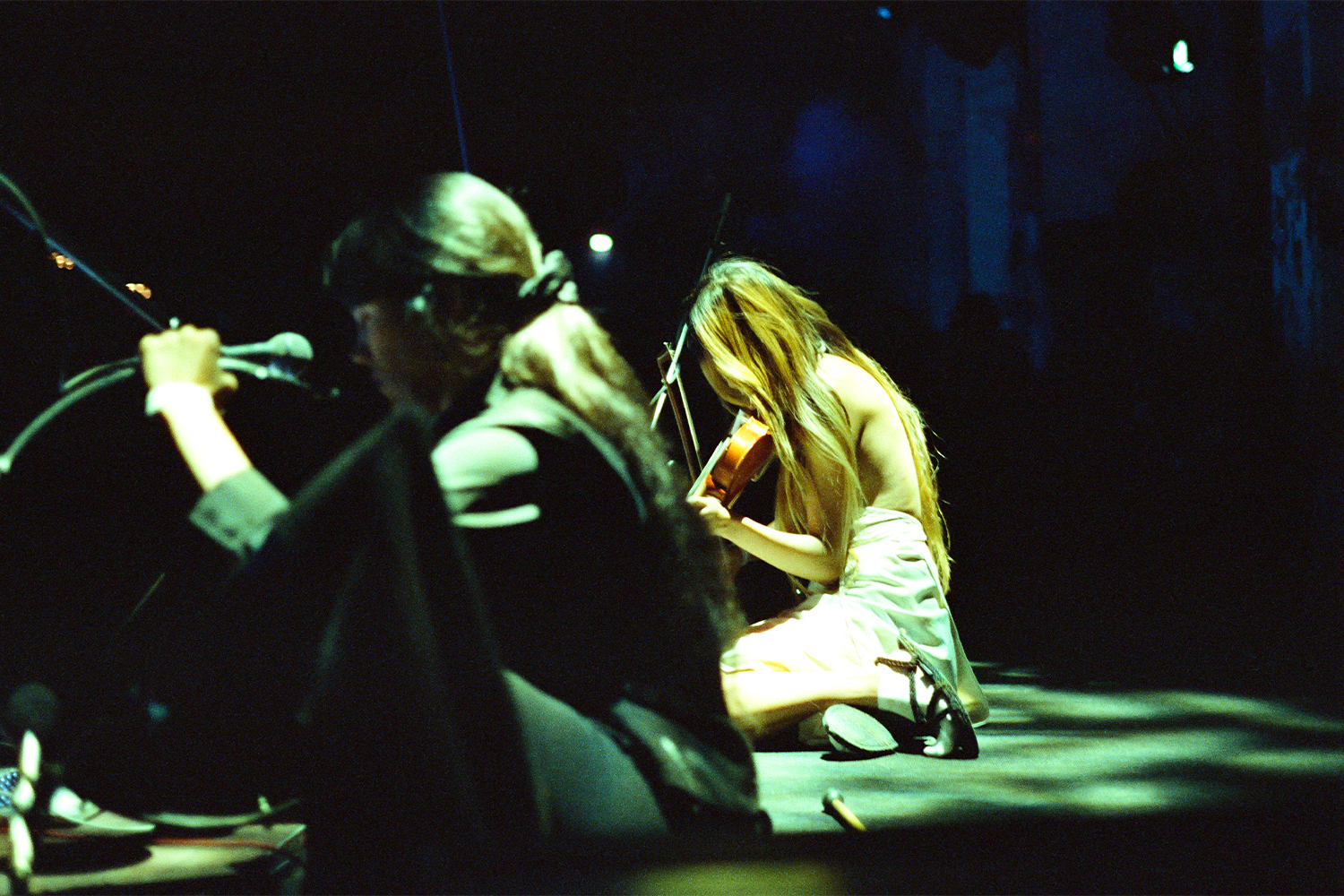

In due course, we embarked on an ascension from the as-far-as-one-can-tell below-ground levels of Kraftwerk, going toward a higher point of the building with Tino Sehgal’s This Ornation (Atonal Remix), originally performed in 2018 and reenacted for the 2021 iteration of this festival. Adhering to Sehgal’s working trajectory, characterized by immateriality, we underwent a sort of breakaway (or intermission) from the exhibition’s chronologically ordered audio-visual displays. A performer summoned us, the group, by treading slowly up the narrow winding stairwell, as we deliberately paced ourselves behind him. At first, we caught on to moving hand gestures framed by the spiraling handrail one story above us as the initial introduction to Sehgal’s performance piece. Comparable to being enticed by the mythological winged sirens, the performer emitted indecipherable howls and constant hums that were acoustically enhanced in the stairwell. We stopped at the top of the staircase, facing the performer, and as we proceeded closer the performer’s voice softened, fostering an intimate exchange of gesture and voice between onlooker and performer.

Following this gradual going through varying sonic and performative maneuverings in restricted spaces, normally unseen by larger audiences, we, the group cluster, ultimately disbanded into the main hall. The exhibition was now no longer confined to a structured linear progression across chronologically arranged works. We could explore the dimly lit central main hall and stumble upon the works disseminated in the immense space. The pieces on display were seemingly situated to accommodate a sense of being uncovered, convened by subtle lighting treatments, for example, throughout every secluded side room or hallway attached to the hall.

Nerv Centre (2021) is Sung Tieu’s installation in a room called the Schaltzentrale (control center), accessible from the power plant’s main hall. The work conjures the exhibition’s introductory “psychoacoustic effect” (as an entryway for “Metabolic Rift”) along with the histories and widespread practice of espionage and psychological warfare enacted by the state during the Soviet occupation of the GDR. Nerv Centre approaches more recent chapters in the ongoing history of psychological warfare and surveillance control. In August, two American diplomats in Hanoi showed symptoms of “Havana syndrome,” which causes brain injuries and other bodily dysfunctions in victims, likely caused by undetected directional energy from some kind of acoustic weapon. US Vice President Kamala Harris’s visit to Vietnam was delayed because of the incident. Tieu’s artistic research works from historical accounts such as these to arrive at the onerous score Ville Haimala and pervading lights made in collaboration with Federico Nitti. On its own, Nerv Centre is a visceral and abrasive sensorial stimulation that touches upon the violent histories of when sound is enacted in surreptitious government operations — one that’s “pulled together by energetic consonance,” as stated as the encompassing concept for “Metabolic Rift” in the curatorial statement for this year’s commissioned works.

Marina Peterson, the author of Atmospheric Noise, wrote in a recent essay titled “Moving Between Thinking through Helium,” published earlier this year in Duke University Press’s liquid blackness journal: “If our senses are so enmeshed in immateriality, why insist on the solidity of skin and bones as defining a body, and not the air of breath, folds of skin as it turns inside, fluids of blood and tears and sweat, the electricity of cells and nerves? With this kind of movement, how do we even hold ourselves together?”

Although helium is a chemical element, it resembles sound in that it is essentially a “kind of movement” carried by air. Both are subjected to a rift, being transformed, absorbed, circulated, resonated — a kind of moving onward without clear or definite shapes or structures. Thinking through helium, as Peterson suggests, means thinking through an unsolidified form: to be formless and sensing, as a perpetual pathway, or tending to a wearisome series of steps – as components needed for activating manifold impacts. Without this as a requisite, how can we surmount or even begin to sense the fissured present? How do we even hold ourselves together?