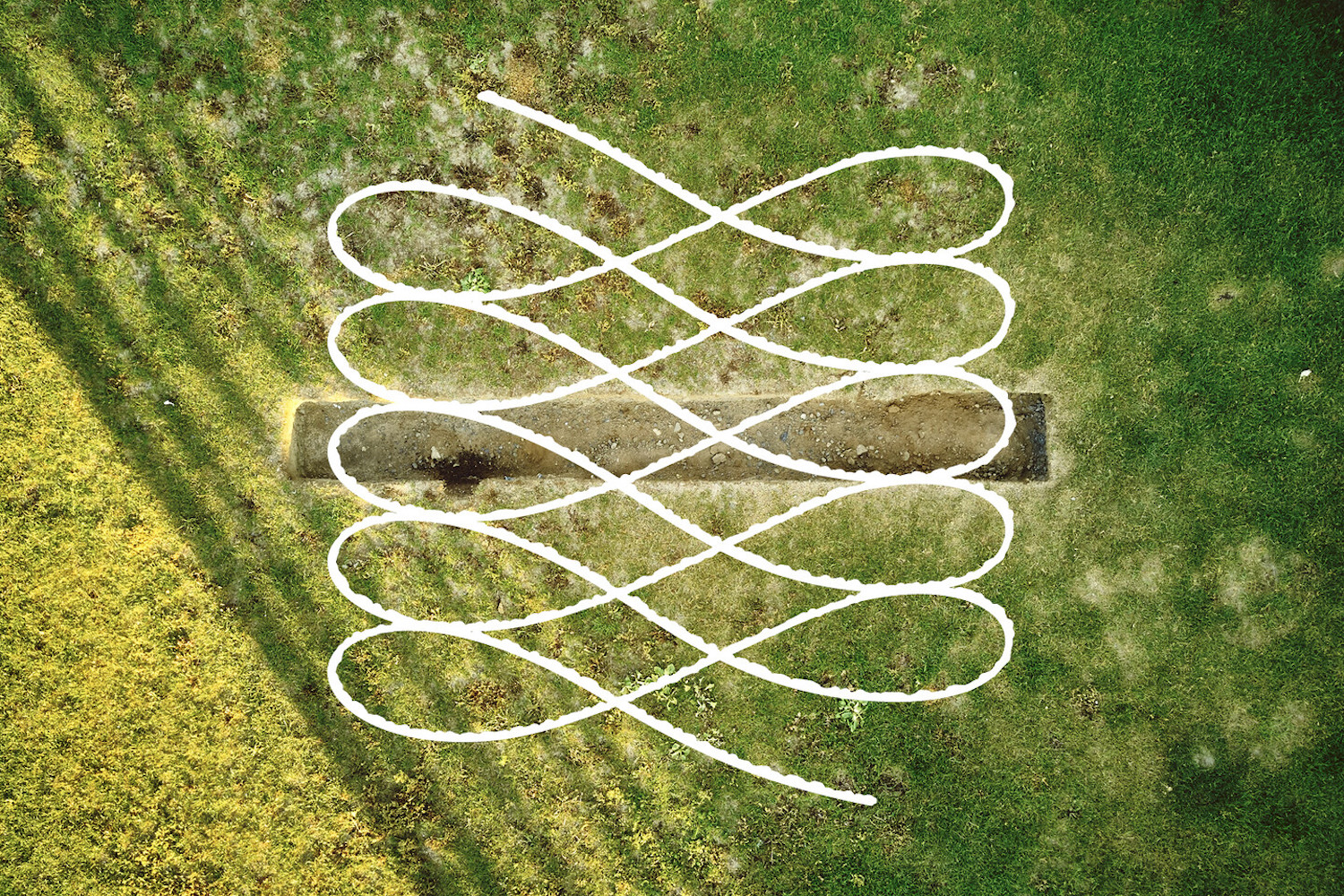

Janet Echelman, 1.78, 2021. Senate Square, Helsinki. Fiber, Buildings and Sky combined with Colored Lighting. Fibers are braided with nylon and UHMWPE (Ultra high molecular weight polyethylene). Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Ella Tommila/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Paweł Althamer, Seven Prisoners, 2020. VR short film. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Kyungwoo Chun, Bird Listener, 2021. Sound, drawing. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

ATTAKWAD, Hype, 2021. Bronze. Donation by the artist to Helsinki 2021. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Pasi Autio, Bird Disco, 2021. Performance.

Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

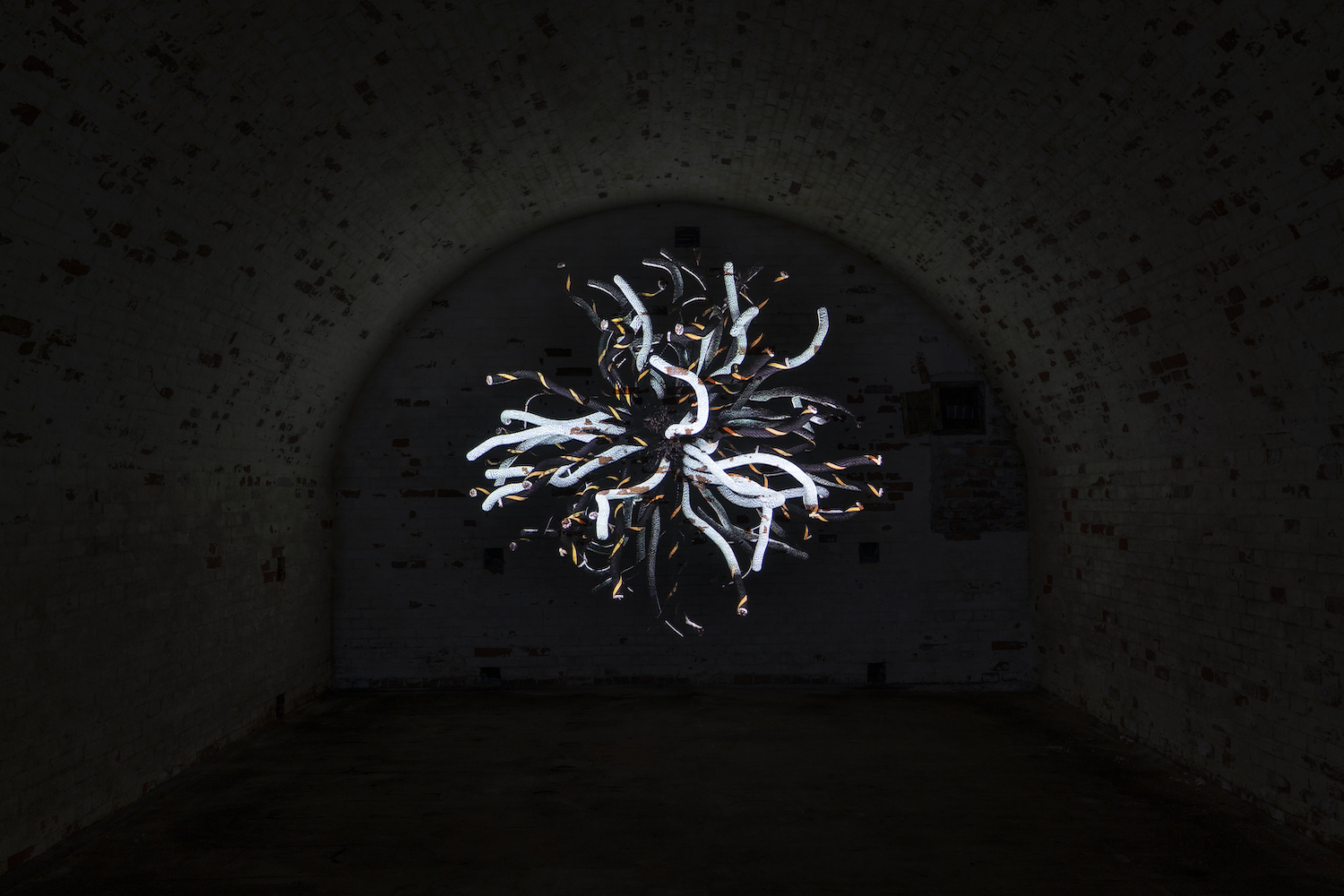

BIOS Research Unit, Vallisaari Research Station, 2021. Installation. Multidisciplinary research, generating data to support policymakers, animation. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Baran Caginli, Carbon as a Political Molecule, 2021. Fabric and found footage archive. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Kyungwoo Chun, Islands of Island, 2021. Installation based on performance. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Katharina Grosse, Shutter Splinter, 2021. Acrylic on plywood, ground and wall. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Hanna Tuulikki, Under Forest Cover, 2021. Single channel film hologram, five-channel sound, birch tree trunks, viewing platform, curtains. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Honkasalo–Niemi–Virtanen, Lazarus, 2021. Multimedia installation. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

The biennial is a “hegemonic machine”1 (Oliver Marchart) intended to “mediate the local, national, and transnational”2 while being linked to a specific territory and its cultural representation. Nora Sternfeld refers to the development of their diverse forms in her podcast3, and notes that in the beginning the biennial was an economic format that played with aspects of spectacular attraction and nationalism. An example would be the infrastructure of the oldest biennial, the Venice Biennale (1895), which was built on the principle of accumulating capital in order to manifest strength by representing the identity of the state through culture surrounded by national pavilions. The Venice Biennale was also intended to increase the city’s tourist appeal. It was in the 1950s that biennials showed a shift toward transnational interest, as seen in the Bienal de São Paulo (1952) or documenta in Kassel (1955). This led to a transnational alliance that existed until 1989 and the emergence of the neoliberal world and approaches like that of Okwui Enwezor at the second Johannesburg Biennale in 1997 — practices that challenged hegemonic constructions. It is interesting to observe the political aspects and mechanisms hidden behind these artistic representations. The current exhibition “documenta. Politik und Kunst” in Berlin (Deutsches Historisches Museum, through January 9, 2022), which presents the political history of documenta during the Cold War, shows the extent of the power of representation and the possibility of getting rid of heavyweight participants with biographies linked to political affiliations — like a spell to cleanse biographies of Nazi relations. Even if it proposed the visibility of an art made invisible by the Nazis — and Jewish artists were almost absent, as were artists from the former Eastern bloc — documenta was and still is a significant place of negotiation and encounter between artists, intellectuals, theoreticians, and the public.

Let’s go back to the economic aspect — mass tourism — of the biennial or other types of art events (as in the case of Documenta). This can lead to cultural gentrification — the construction of new but temporary infrastructures that may leave a city, or parts of it, seeming like a “ghost town” once the event is over, or, on the contrary, result in a trendy new neighborhood.

Wanuri Kahiu, Pumzi, 2009. Short film.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Marja Kanervo, Block A, 2020. Site-specific installation. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Kirsi Halkola/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Zodiak presents: Kärkkäinen & Tarvainen, The Wall, 2021. Site-specific installation. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Samnang Khvay, Preah Kunlong (The Way of the Spirit), 2016–2017. 2 channel video work.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Jussi Kivi, Heritage Room of Local Artefacts and Anomalies / Museum of Timelessness, 2021. Site-specific installations. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Laura Könönen, No heaven up in the sky, 2021. Painted diorite.

Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021 and the City of Helsinki.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Hayoun Kwon, 489 Years, 2016. 3D animation. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Tuomas A. Laitinen, ΨZone, 2021. Site-specific installation: 3D animation, glass, ultrasonic speakers. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Niskanen & Salo, A Scene. Video installation, 24-hour loop. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Niskanen&Salo.

Niskanen & Salo, A Scene. Video installation, 24-hour loop. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Niskanen&Salo.

Niskanen & Salo, A Scene. Video installation, 24-hour loop. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Niskanen&Salo.

The recent Helsinki Biennial and its behavior is an interesting example. It should be noted that it is the first edition5 of this biennial, whose future is uncertain. The Helsinki Biennial was supposed to open in 2020 but, because of the pandemic, it was postponed to 2021. However, one has the impression that this biennial was only opened for the purpose of being open — that is to say that the organizers no longer had the option of moving it (for several reasons, notably time-sensitive financial ones), and opening it may have been a strategic, logical gesture: almost no one will be able to visit the event, so the organizers take on little risk. Meanwhile, creating a history of its having existed will help administratively to make it happen the next time. Some local artists and critical thinkers may shrug and say that this manner of “representing” the local scene internationally could be less degrading.

Jaakko Niemelä, Quay 6, 2021. Scaffolding, painted wood structures, water pipe, water pumps. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Teemu Lehmusruusu, House of Polypores, 2021. Mycelium structures, rotting wood, organ pipes, sensors, solar power. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki. Biennial 2021.

Dafna Maimon, Indigestibles, 2021. Installation, video, performance. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Antti Majava, Excursions on Actual Transit-ions, 2021. Film, HD video. Vindö 40 sailing boat, 10kW electric engine/generator, recycled 10 kWh Lithium-ion electric car battery, solar panels, backup generator. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Inga Meldere, Repeating Pattern, 2021. Site-specific installation. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Birit & Katja Haarla, Outi Pieski, Guhte gullá / Here to hear, 2021. Multi-channel video installation. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Mario Rizzi, BAYT (KOTI/HOME), 2013–2019. HDCAM film. Courtesy of the artist and Sharjah Art Foundation. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Margaret & Christine Wertheim and the Institute For Figuring, Helsinki Satellite Reef, 2021. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Janet Echelman, 1.78, 2021. Senate Square, Helsinki. Fiber, Buildings and Sky combined with Colored Lighting. Fibers are braided with nylon and UHMWPE (Ultra high molecular weight polyethylene). © Ella Tommila/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Sari Palosaari, Eons and Instants, 2021. Rocks, rock dust, snail dynamite, cobalt (CoO & Co-Al-Zn), spodumene, zink acetate, copper carbonate, brass, steel. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Alicja Kwade, Pars pro Toto, 2018. 8 natural stone globes. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021 and Kalasatama Environmental Art Project. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Why was the Biennial opened with this insensitive vision toward the rich reality of the local scene, lacking the development of alternative education platforms, a reflection of situated knowledge, or publicness? How do we explain the absence of critical self-reflection, or reflection on what the “public commons” might be in this context, or, finally, the carelessness about the space in which the Biennial is located? In this context, we can point to the problem of “branding” in relation to the city of Helsinki, which is faced with widespread privatization: a public sector that behaves like the private sector. The organizers of the Biennial, the Helsinki Museum of Art (HAM), seem to have a monopoly on the art scene; the artists represented are artists from the HAM’s collection, artists who have recently had a solo exhibition in Helsinki. Another problem was the specious content. To underscore the real urgency we face, a curatorial choice was made to locate the Biennale on an uninhabitable former military island called Vallisaari, which by its character raises current issues such as, for example, sustainability and ecology (the island is a nature reserve), as well as issues of military force, war, water as a symbol of escape, connections between countries, continents, etc. In fact, these issues seem to serve only as a pretext for the existence of this biennale, in keeping with the need for “themes” to address in order to be able to justify the relevance of an international mega-show, rather than asking more rigorous questions. For example: How is art a part of Helsinki society, and how could one develop the latter themes in all their integrated complexities and within their specific locality? What is also surprising is that Vallisaari has turned into the “island of the biennial,” with new accommodations, spaces, cafes, etc. Paradoxically, the entrance fee is free, but there is no way to get there other than to take a private boat. The island, now gentrified by expensive infrastructure, will have a surprisingly limited lifespan, as the next edition is supposed to take place in another unoccupied part of the city.

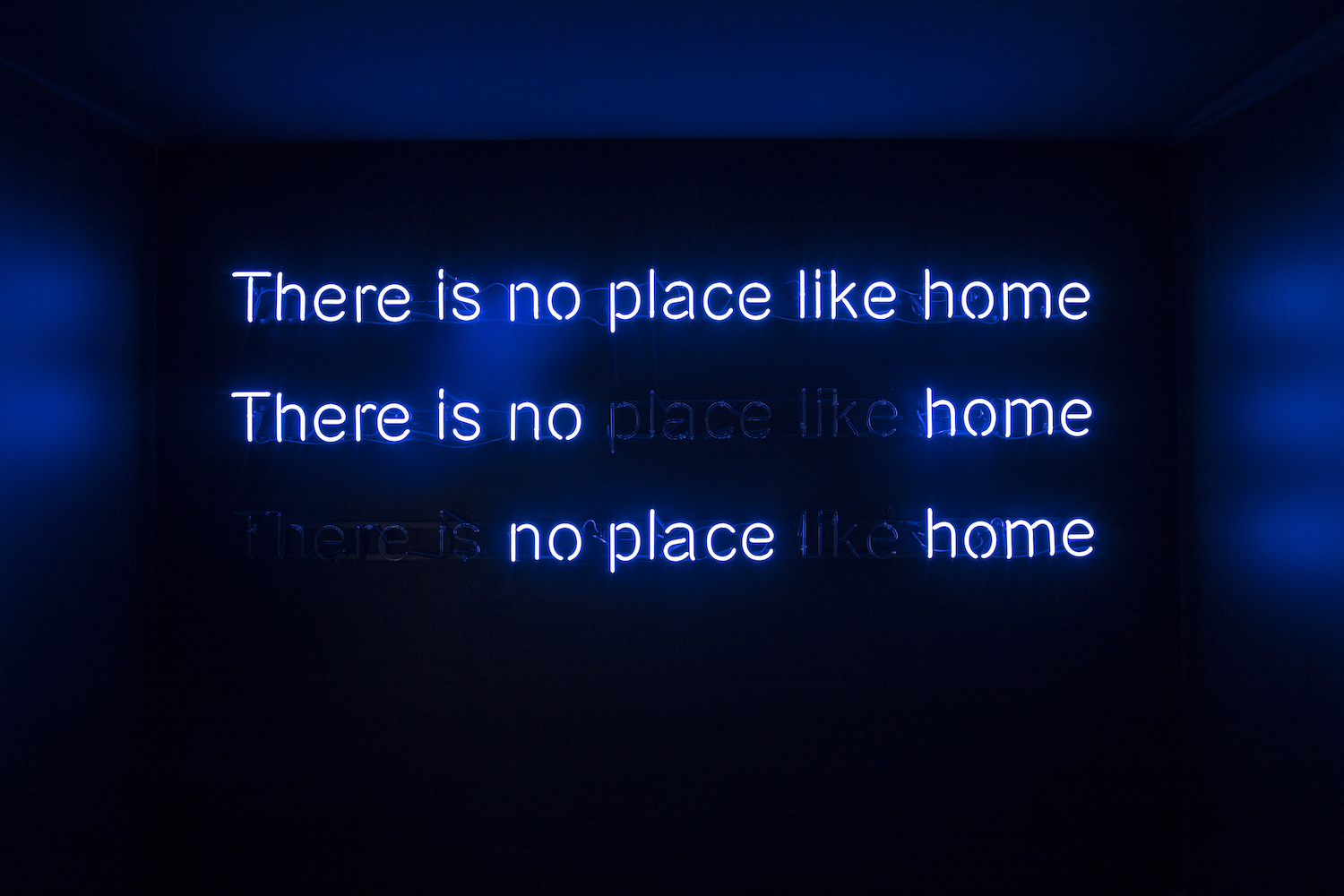

Baran Caginli, Expressions, 2021. Neon sign. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Maaria Wirkkala, Not So Innocent, 2021. Site-specific installation.

Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Samir Bhowmik, Lost Islands, 2021. Performative expedition, video installation, cable installation and assemblage. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

IC-98, Abendland (II: The Place That Was Promised), 2013. 1 channel HD video installation. Courtesy of HAM Helsinki Art Museum Collection.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller, FOREST (for a thousand years…), 2012. 22 channel audio installation on a 28 minutes loop, loud speakers mounted in a forest setting, amplifiers, playback computer, camping trailer. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Alicja Kwade, Big Be-Hide, 2019. Granite, aluminium, mirror, powdercoated stainless steel.

Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021 and Kalasatama Environmental Art Project.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Meiju Niskala, It Occurred to Me, But a Bit Too Late, 2021. Functional audio essay. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Topi Kautonen (1921-2011), Paintings from Private collection.

© Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

EGS, Archipelago of Past and Future: The Island of Last Winter / Kellosaari / Hietasaari / Laukkasaari / Kana / Sompasaari / Dire Straits of Capitalism / Isle of Democracy, 2021. CNC-machined wood, steel, paint and varnish. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021 and Kalasatama Environmental Art Project. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Tadashi Kawamata, Vallisaari Lighthouse, 2021. Site-specific installation. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021. © Maija Toivanen/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

Rirkrit Tiravanija & Antto Melasniemi, THE SEA THAT YOU SEE IS NOT WHAT THE OTHERS SEE, 2021. Event-based and spatial concept for HAM corner. Commissioned by HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

© Kirsi Halkola/HAM/Helsinki Biennial 2021.

How is it possible that the Helsinki Biennale is now reproducing a model that apparently needs to be completely transformed?

On March 28, 2020, during the height of COVID-19, Mediapart published an article called “Biennales, fin de partie?”6 In June 2020 the platform oncurating published its 46th issue, called “Contemporary Art Biennials – Our Hegemonic Machines in Times of Emergency.”7 As typically anti-ecological events symptomatic of an unregulated art market, there has long been an urgent necessity to reinvent globally connected exhibitions. Their organizers should, in particular, think of the causes of problematic labels such as a “capitalist machine considering culture as entertainment” that results “from the neoliberal market logic of ‘spectacular capitalism’” (Okwui Enwezor).8 Is it not more necessary than before that the exhibition becomes a “space of action,” a space of possible social change — as mentioned by Adam Szymczyk during the discussion “Documenta as a Common”9 with ruangrupa and Nora Sternfeld about the upcoming documenta 15? Thinking of the biennial “as a tool and process through which we change the way in which contemporary art institutions are run” toward a kind of “biennale-as-institutional-critique”10 in continuing to consider nomadic art settlements seems to be the most logical response to neoliberal and populist cultural policies.

However, the problem seems to take the position of saying that we are naive to think of more solidary and equitable conditions while being invaded by the capitalist system in which we live. Yet isn’t the acceptance of this contradiction, rather than going against it, exactly the same kind of “comfort” that this capitalist system reproduces?

This text was written after an unofficial discussion between artists, activists, and theorists about the meaning of the Helsinki Biennial, held on August 25, 2021, at a local art school.