Lucky reinterpretations do exist. In one of his best-known texts, Walter Benjamin describes Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920) in the light of his theses on the philosophy of history. “Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees a unique catastrophe that piles ruins up and throws them at his feet.” Heidegger does something similar in his Origin of the Work of Art, when he resorts to Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes (1886) to explain how art is “the truth of beings setting itself to work.”

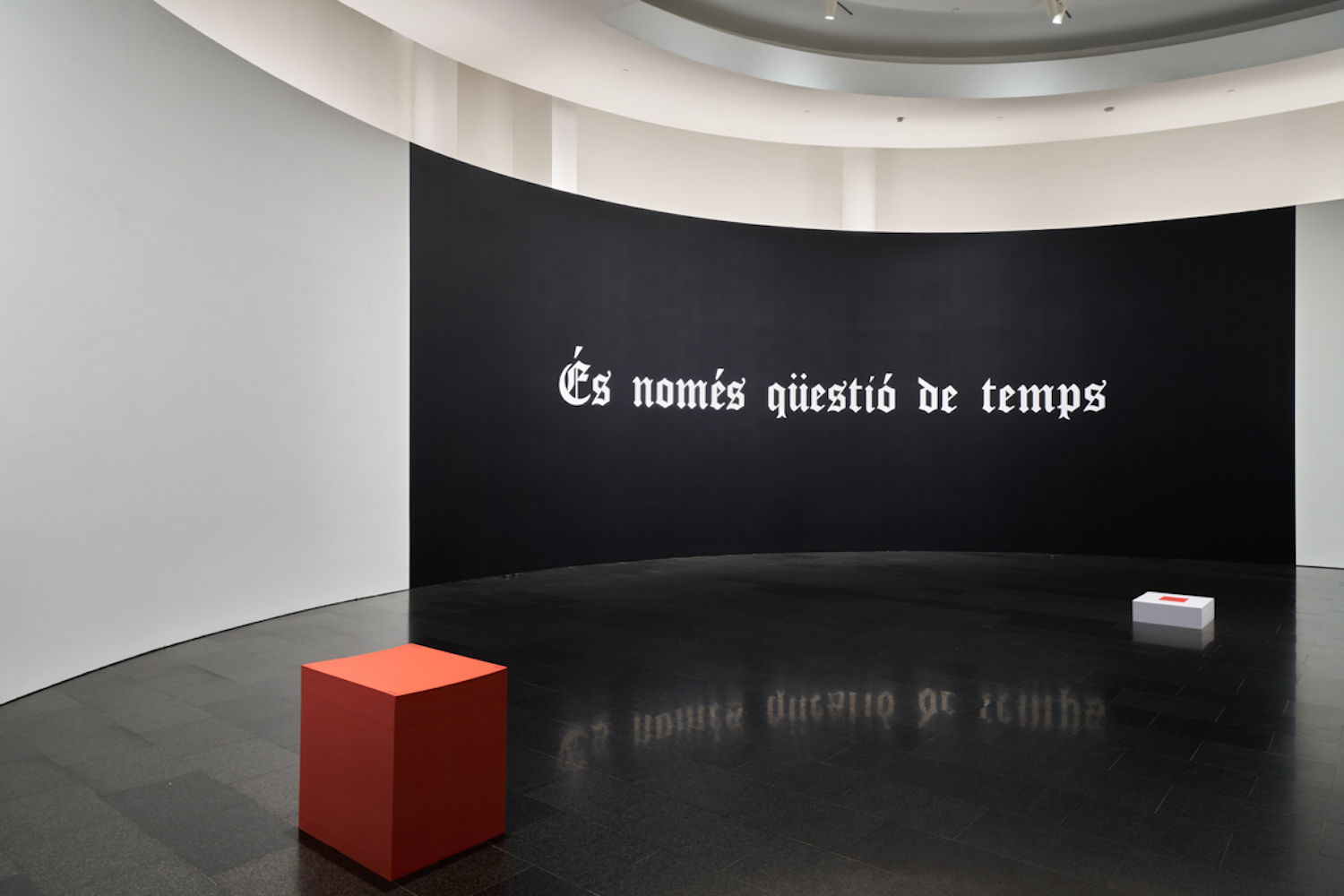

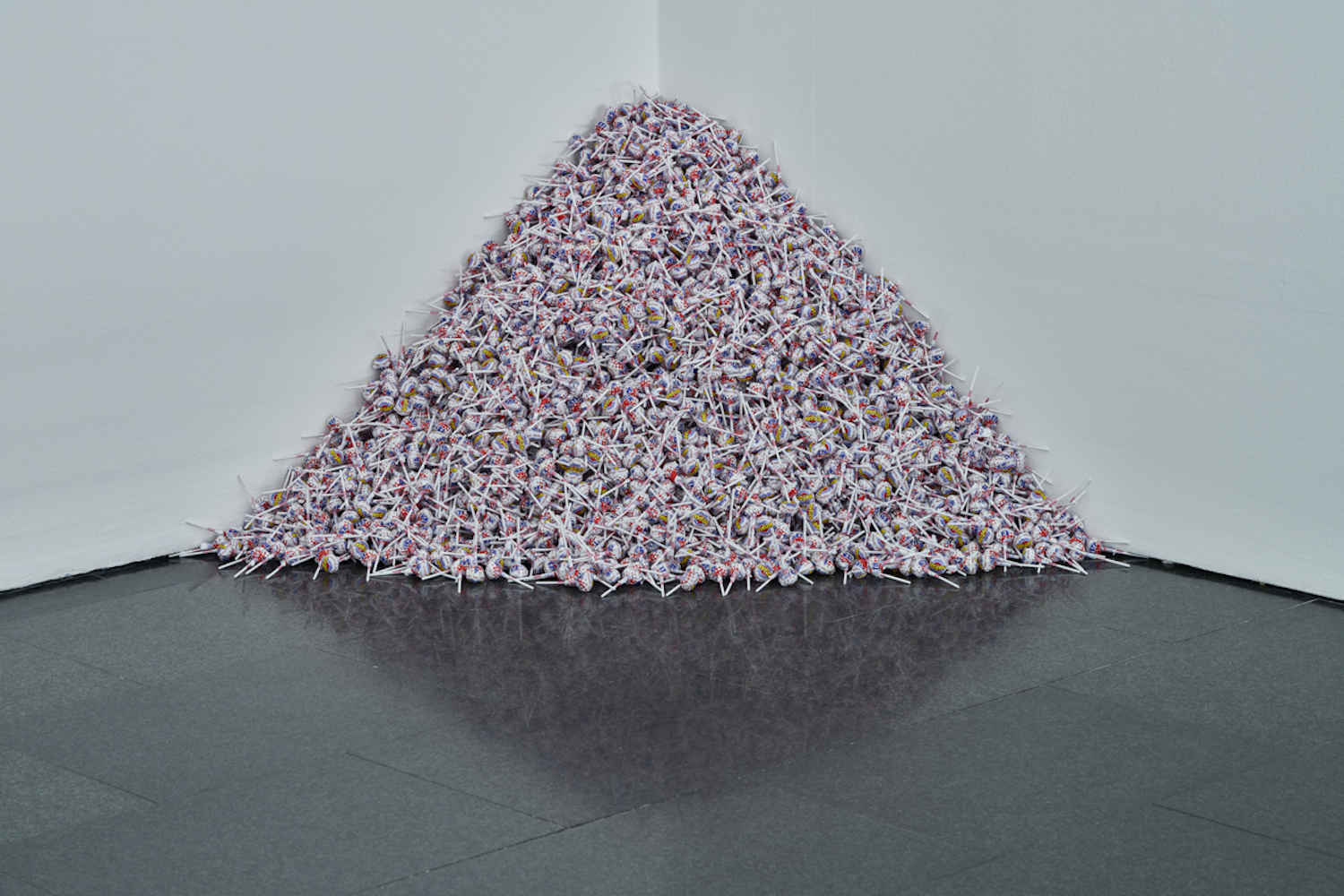

These reinterpretations are valuable in that they expand the meanings of artworks, generously opening up new hermetic possibilities. The retrospective that the MACBA dedicates to Felix Gonzalez-Torres (Guáimaro, Cuba 1957–Miami, 1966) aims to “present a political interpretation […], especially one concerning Spain, the American continent and the Caribbean, their shared histories and points of contact.” To this end, Tanya Barson, the curator of the exhibition, allowed herself to swap fascisms and oppressions, so that Gonzalez-Torres’s work can be read as a critique of Donald Trump, Franco’s repression, or the specific problems of the City of Barcelona. If the conflicts referred to by the artist’s work had already been overcome, equating all these calamities would be shortsighted and absurd; and as they are still lurking, it is grotesque. The free re-signification reaches its peak when the exhibit label of Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1987–1990) tries to link the artwork — two round and synchronized wall clocks that will gradually become out of phase due to the exhaustion of the batteries — with the adoption of the German time zone in Spain, after the Civil War.

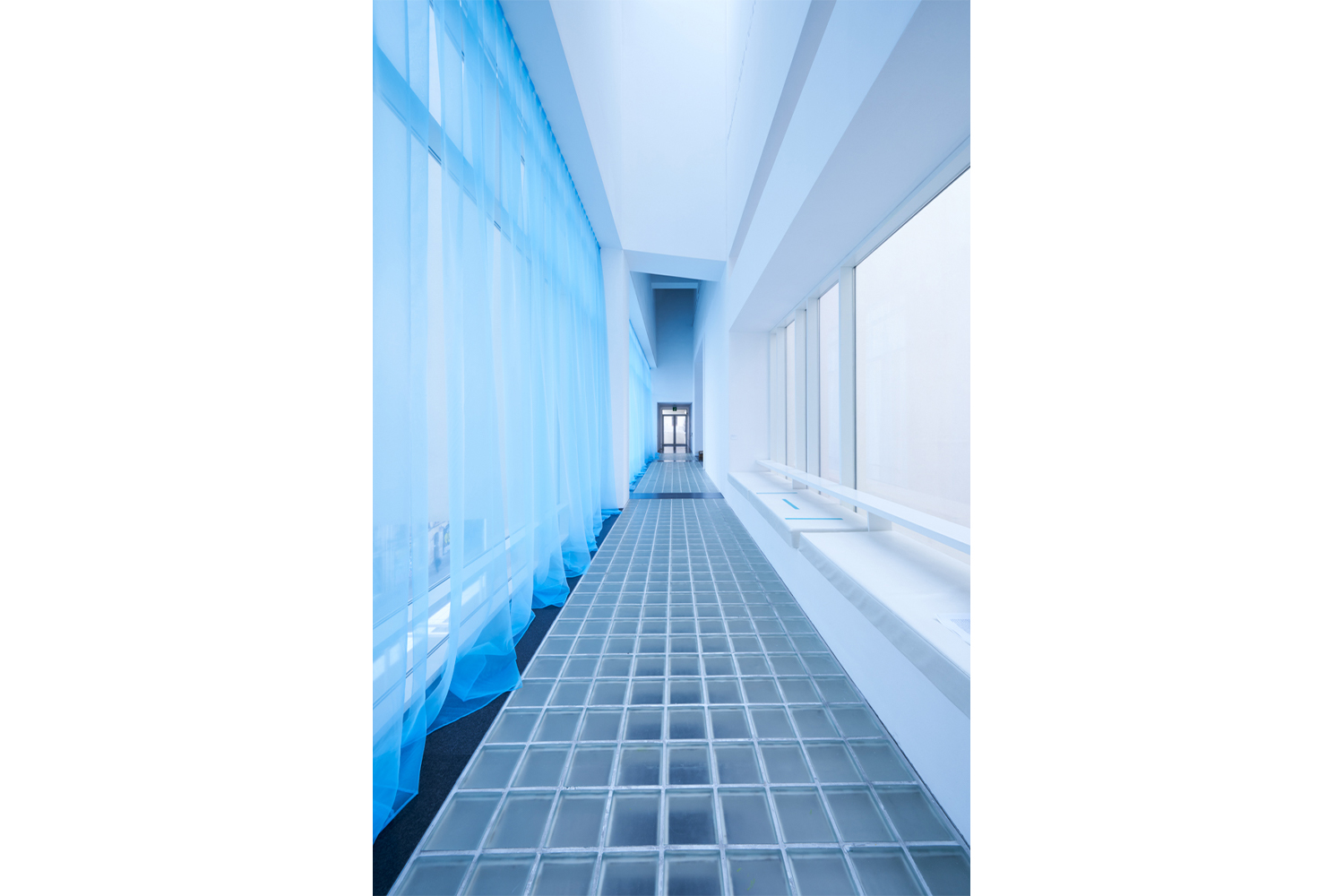

This is complemented by a confusing and disjointed staging. At some point, the visitor may suspect that the artworks have been spaced out in an attempt to simply fill the four rooms across which the exhibition is distributed. Exhibit labels are placed three meters from one another, so viewers have to participate in a gymkhana if they want to read titles and dates. To make matters worse, there are poorly installed artworks (posters attached to the wall with hardly any care, leaving spaces between them visible), and the texts that explain each room are full of grammatical errors.

Sadly, these obvious mistakes diminish the viewer’s experience of Gonzalez-Torres’s extraordinary work. Critiques of the art market, embodied in works whose reproduction is unlimited and whose distribution is free, are presented in a simplistic way, letting visitors simply collect memories. Intimacy fades away in a scattered staging, and the large posters — so representative of the artist’s work — are presented as mere decorations.

Gonzalez-Torres once said that he needed the public to complete his job. Unfortunately, this exhibition deactivates the power of the work it presents, turning it into a triviality that depicts the terrible experiences revealed by the work of the Cuban artist as rudely equated with domestic conflicts whose violence and relevance are intended to be enlarged. Oh, please.

(Translated from Spanish by Ana Laura Esposito)