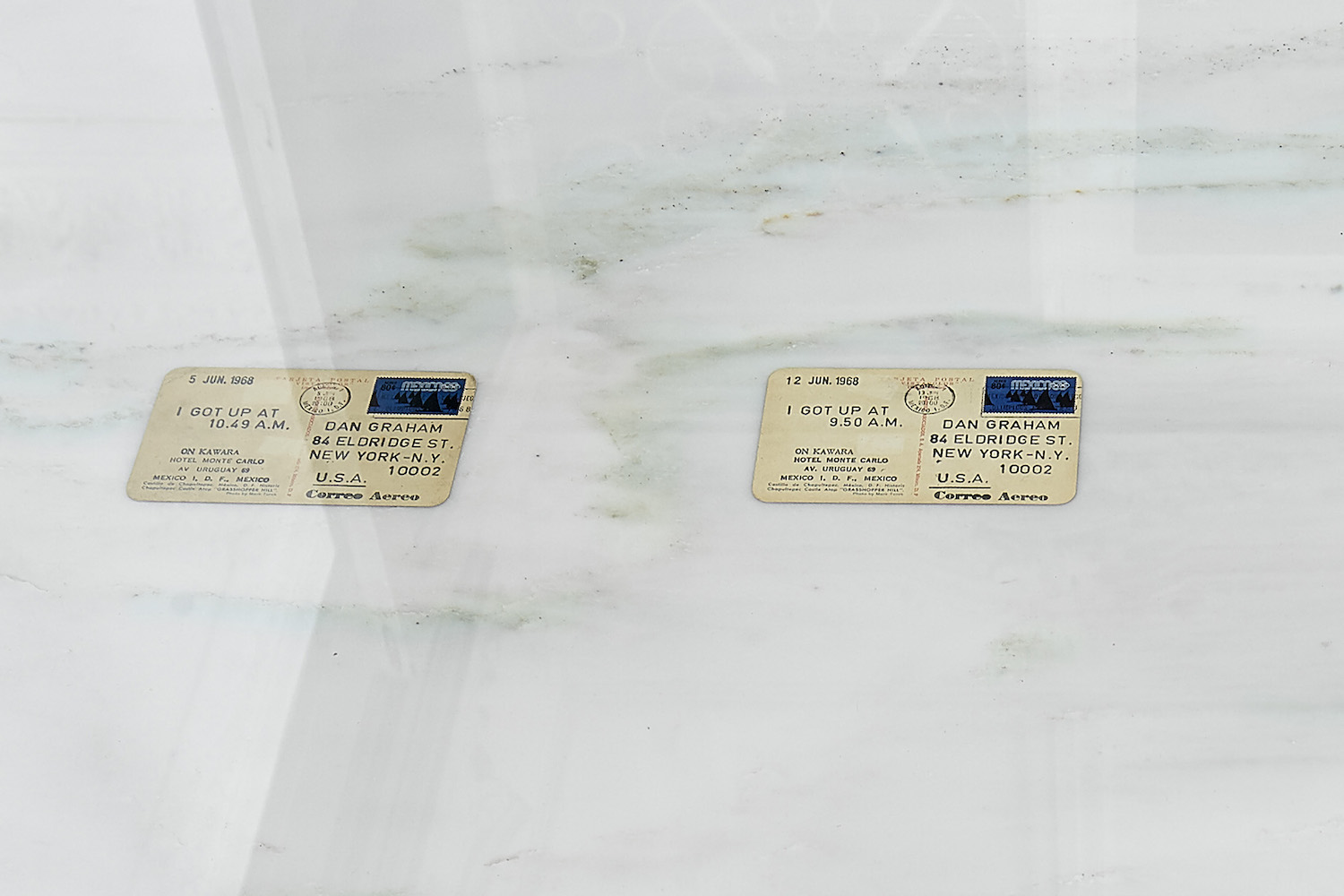

Four identical postcards displayed in the gallery’s entryway bear the stamped, enigmatic phrase “I GOT UP AT,” followed by the time that the sender awoke. Composed by On Kawara throughout June 1968 while the artist was living in Mexico City and sent to Dan Graham in New York, the postcards inaugurate the structure of the exhibition “I GOT UP,” curated by Pierre Bal-Blanc at Hot Wheels Athens, whose title is taken from Kawara’s cryptic pronouncement. In its unsettling simplicity, Kawara’s repeated statement paradoxically conjures the intimacy of sleep and awakening via conceptualist strategies that hew to the impersonal and the anti-narrative. Yet the I GOT UP postcards further implicate the body’s existential rhythms as historical markers. Their postage stamps depict the iconic logo of the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, whose tumultuous history is inseparable from the brutal suppression of the Mexican student movement and the broader legacy of global liberation struggles during the Cold War. By assembling works of conceptual art alongside those of contemporary artistic practitioners in Athens, Bal-Blanc’s exhibition draws on Kawara’s ambivalences as a critical resource for reimagining how an exhibition can forge a collective score for politicizing new forms of contingency and aliveness.

Adjacent to Kawara’s postcards is a work by their recipient from the following year, a reproduction of Dan Graham’s INCOME (OUTFLOW) (1969). In Graham’s text piece, the artwork takes the form of a magazine advertisement that sells shares for Dan Graham Inc., a fictionalized corporation through which the artist aimed to pay himself the average salary of an American citizen. Circulated in magazines such as Life, Artforum, and the Wall Street Journal, Graham’s advertisement is an ironic gesture that expropriates the self by way of its monetization. Yet Graham’s intervention mirrors Kawara’s experimental network of public circulation, as both artists subvert the functions of institutionalized systems like advertising and the mail. By self-reflexively probing how both art and money operate as “a social sign,” Graham sought to collectively redistribute the economy of art to prioritize the needs of the artist.

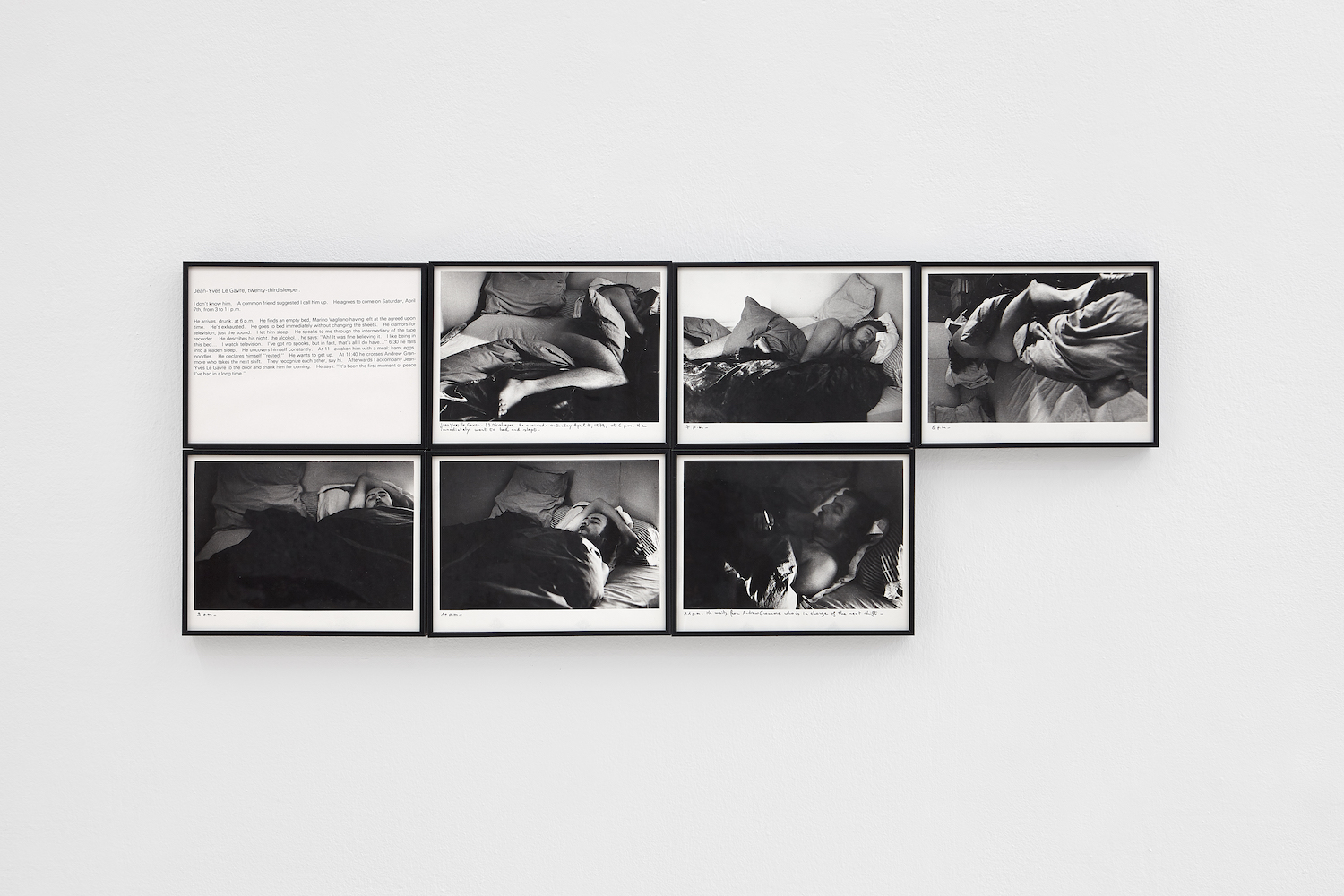

In the back gallery, an excerpt of photographs and text from Sophie Calle’s The Sleepers (1980) visualizes the affective and bodily dimensions of sleep that Kawara dematerializes in language. In her project, Calle invited strangers to be documented sleeping in her bed in consecutive shifts. The resulting photographic and text series oscillates between the voyeurism of Calle’s gaze and the gestures of care that underlie her staged hospitality. In the exhibited selection, Calle’s black-and-white photographs of Jean-Yves Le Gavre attest to the vulnerability and mortality of the sleeper’s contorted body, whose sheer physical presence belies that his mind is elsewhere.

Karawa’s I GOT UP postcards and Calle’s photographs from The Sleepers converge as reenacted specters in a series of performances of “getting up” that Bal-Blanc devised to take place at the exact dates and times that Kawara got up in his four exhibited postcards. Across four Saturdays in the month of June, four participants — Hugo Wheeler and Julia Gardener, co-founders and directors of Hot Wheels Athens; an audience member; and Bal-Blanc himself — each stayed overnight in a bed installed in the corner of the exhibition’s main room. Upon getting up, they performed their transition from sleep to wakefulness in front of a morning audience, forging a counter-public sphere from an action associated with the personal and the domestic. After more than a year of pandemic-induced lockdowns and isolation, witnessing an “I GOT UP” performance felt less voyeuristic than Calle’s project and more like a collective ritual of attunement to modes of everyday survival. Assembling in the presence of others to watch the performer’s awakening rendered palpable the often hidden labor or undervalued relations of interdependence that make our getting up possible.

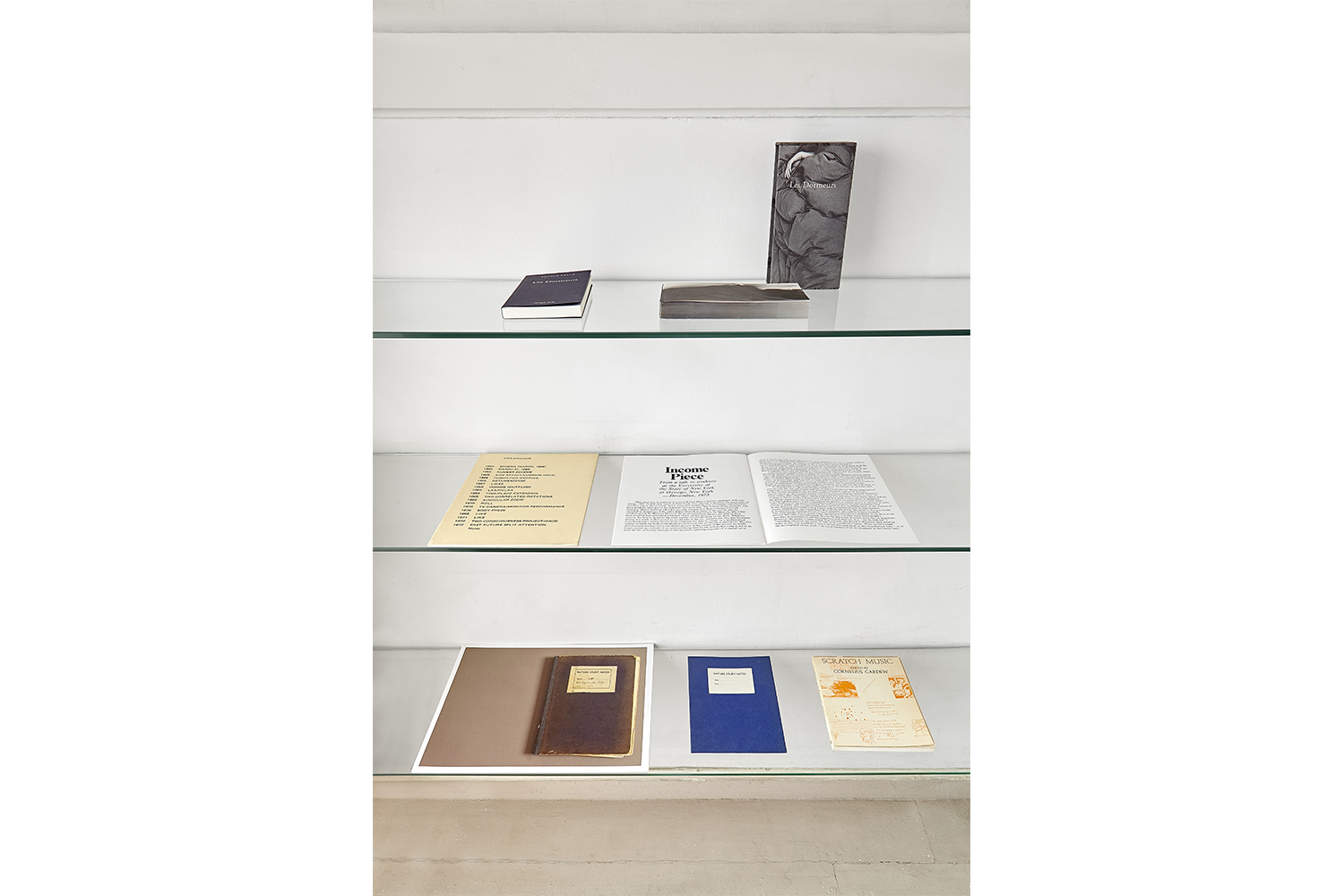

Each Friday night before the “I GOT UP” performances, a second series of performances took place in the gallery. Titled Solo – Nature Study Notes – 1969-2019 [Athens Version] 2021, the multipart work includes the practices of several Athens-based artists — a performance by Georgia Sagri, music by Delia Gonzalez, and garments by the art and fashion collective Serapis Maritime — based on a score that Pierre Bal-Blanc composed in collaboration with them. Bal-Blanc appropriated the score’s structure from Cornelius Cardew’s Nature Study Notes (1969), a series of “improvisation rites” that the English composer authored for the Scratch Orchestra, his co-founded experimental ensemble. Cardew’s rites function as a series of proposals, rules, and constraints for a collectively improvised musical performance. Writing at the time of Kawara’s and Graham’s conceptual experiments with circulation, Cardew partakes in democratizing artistic distribution, noting in Nature Study Notes that “No rights are reserved for this book of rites. They may be reproduced and performed freely.”

The Friday night performances were tightly choreographed to make space for the improvisation and contingency embedded in Cardew’s rites and their collective reenactment half a century later. Selected rites — such as “…with blindfold” or “The more ugly the sounds the more beautiful they become” — were printed atop handsome silk garments by Serapis Maritime. On the garments, the designers also reproduced photographs of the interior spaces of Hot Wheels Athens, which corresponded to the spatial positioning of the clothing throughout the gallery.

The performance’s staged elements of chance began and ended with Georgia Sagri taking a taxi from her house to the gallery and back. Upon arrival, she put on a silk dress with a photograph of the bookshelf in her home printed on the back and one of the gallery’s doors and Cardew’s rite “six deep breaths…” embossed on the front, embodying the transvalued thresholds of private and public. As she put on and took off each garment laid out throughout the gallery, Sagri performed her interpretation of each rite printed on it in alignment with Delia Gonzalez’s ambient modulating soundscape, a musical interpretation of Cardew’s rites. Sagri’s gestures shifted between willfulness and a sense of anxious repetition, defamiliarizing the comportment of the body and embracing its unruliness in interactive proximity to the viewers. In a poignant moment, Sagri waved a silk scarf printed with the rite “Play when you are least expected to” off the balcony of the gallery to the passersby below and to the neoclassical building across the busy boulevard, the Athens Polytechnic on Patission Street. This climactic moment pointed to the site of the Athens Polytechnic Uprising of November 1973, the student demonstration inspired by those of May ’68 that escalated into a widespread and brutally suppressed revolt against the Greek military junta. In doing so, Sagri’s gesture unearthed the revolutionary specters implicit within the performance’s score, glimpsing the past political milieu from which Kawara and Cardew’s conceptual art emerged within the global outpourings of protest that continue to reshape the present.

The performance score was exhibited as a legal agreement co-authored and signed by Georgia Sagri, Delia Gonzalez, Serapis Maritime, Pierre Bal-Blanc, and Hot Wheels Athens. Adhered directly on the wall of the gallery, the contract resembled the political posters pasted throughout the streets of Athens. Aiming to render the collective artwork both transparent and able to be restaged, the contract stipulated the aesthetic elements of the performance and the logistical and monetary conditions of its re-performance and sale. Like the openness of Cardew’s rites, the performance score operates in an open-source manner, as the work’s exhibitionary system is meant to be reproduced as its conditions of publicness are remade anew. The performance raises crucial questions regarding the redistribution of artistic economies. To what extent does a collective artwork challenge institutions by depending on them for their proliferation? How can artworks collectively reinstate modes of transparency surrounding their conditions of production that are too often mystified by the circulation of capital? How can artists collectively articulate new contingencies of publicness today? “I GOT UP” productively dwells in these ambivalences, reenacting conceptualist rites to question societal rules. By gleaning from the political genealogies of conceptualism, the exhibition’s eccentric dramaturgy scores new rituals for subverting institutions and fostering the life of collectivity from within.