In the group exhibition “Homecoming: The Aesthetic of the Cool” — which presents the work of three Ghanaian portraitists, Otis Quaicoe, Amoako Boafo, and Kwesi Botchway, in Gallery 1957’s hollow white cube in Accra — piercing eyes follow you everywhere.

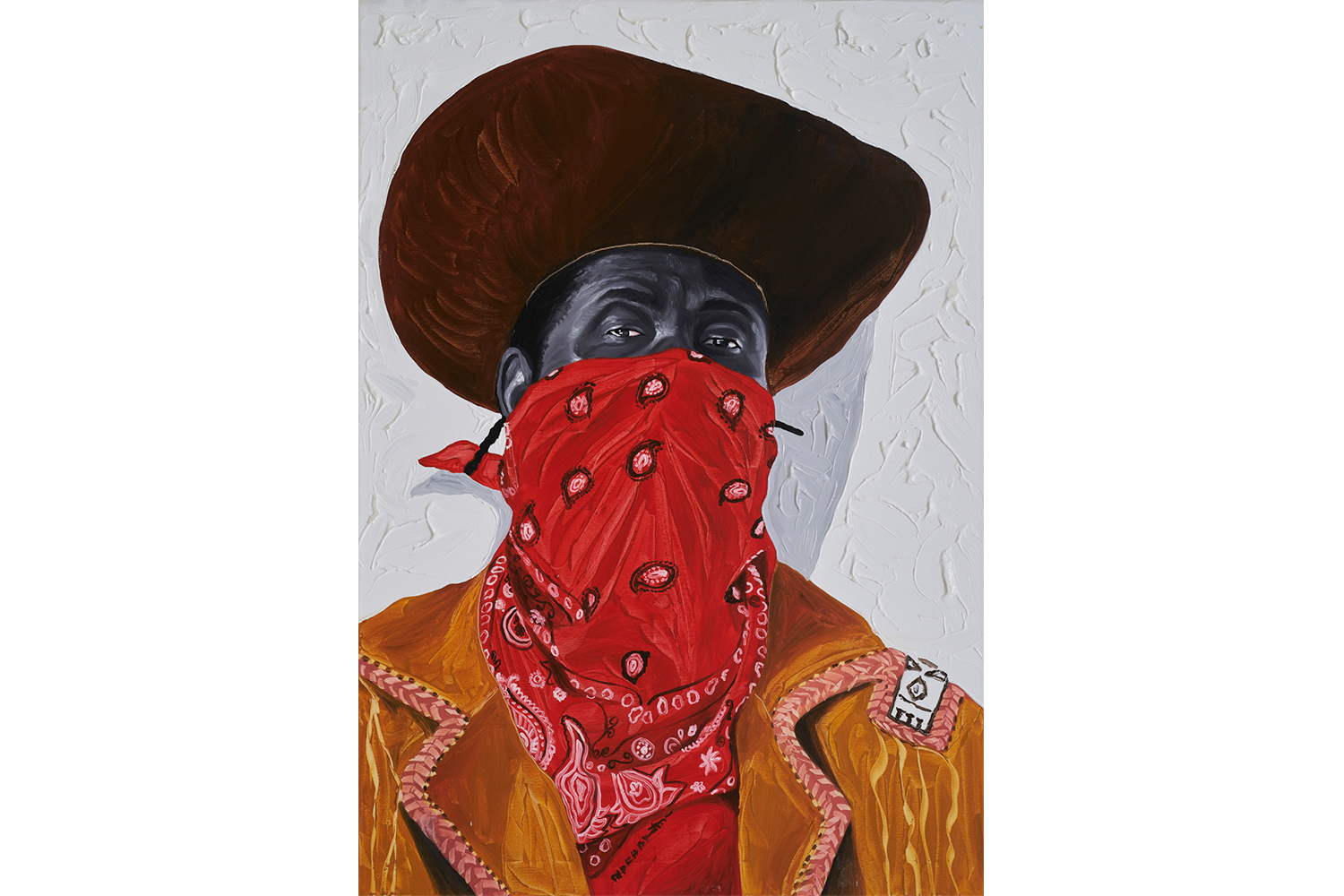

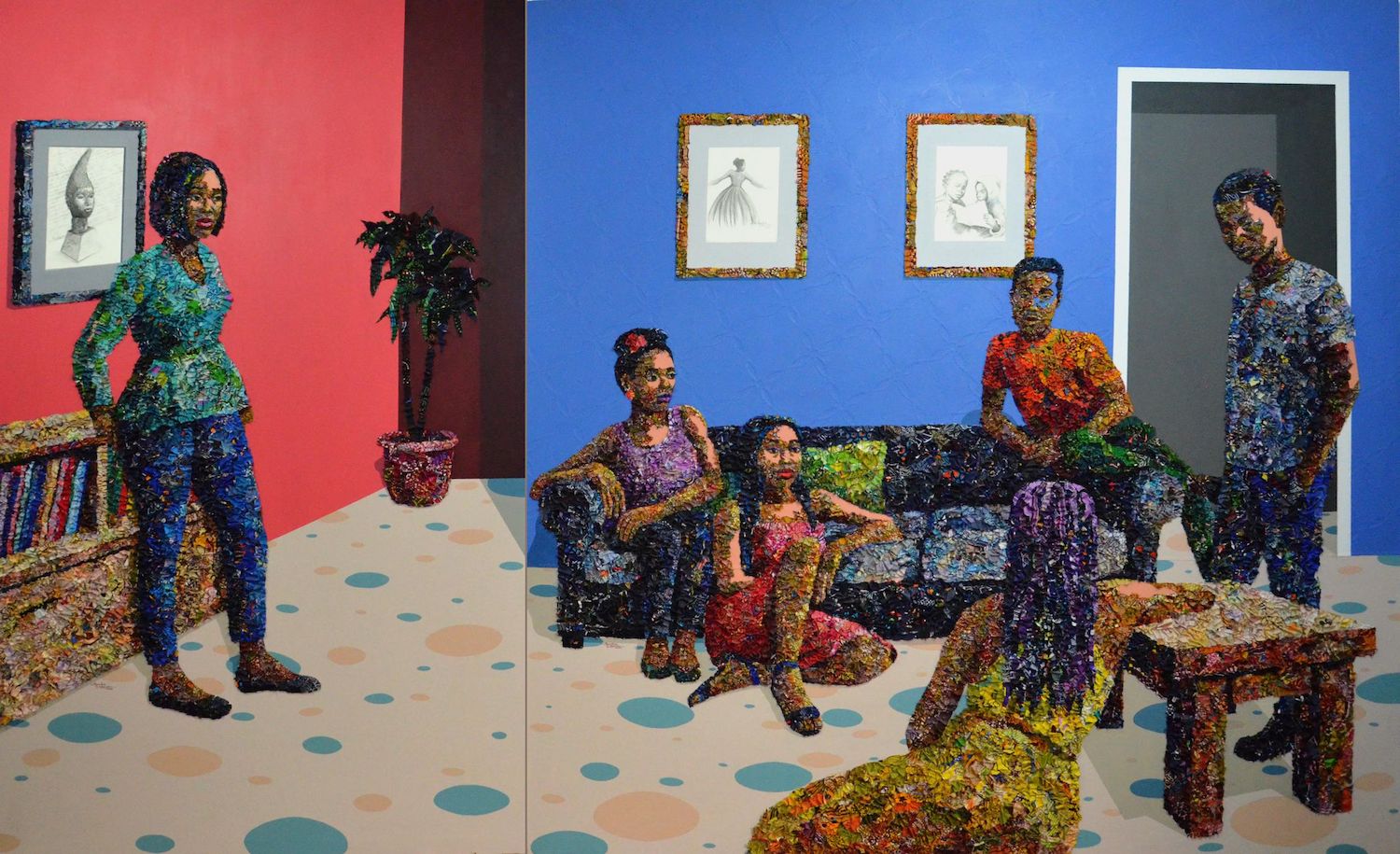

In Quiacoe’s oil-on-canvas paintings Ranger I (2021), Ranger II (2021), and Nana (2020), the eyes are those of a cowboy, smoldering above a red bandana. In Kwesi Botchway’s larger-than-life Fancy Pillows (2021), the sitter is ready for their close up, whimsically dressed for fall in a green sweater, beige vest, and icy blue trousers, while reclining on a red sofa in a pose that’s oddly reminiscent of the promotional poster for the 1999 Hollywood film American Beauty. In Boafo’s finger-painted Sunbathers (2021), five women are kneeling in bikinis, presumably enjoying an afternoon by the beach.

In each scene, the viewer, confronted by the sitter’s stare, is let in on a moment of play or languor. The exchange is perhaps more intense when the sitters are depicted within a background void. Their location is only alluded to; they dominate the frame, center stage. The paintings are stirring in their simplicity, exuding a feeling of familiarity, intimacy. One may not register the technical accomplishment here, the generous use of color as visual language. Instead, one is lost in the gaze of someone they seemingly know, immortalized on the canvas.

This exhibition, held in celebration of Gallery 1957’s fifth anniversary, must be considered as part of an emerging movement of contemporary African portraiture — acknowledged by some critics and the artists themselves — that is fast gaining recognition in the global north. The racial reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd, with the many critical questions it raised regarding racial injustice, also drew attention to the inadequate representation of Black people and their work across various sectors, including the visual arts. Over the past year, several landmark exhibitions showing Blackness in a new light — particularly as defined by African artists — have been staged across the world, with art institutions on the African continent seizing the moment. In September 2020, the African Artists Foundation based in Lagos, Nigeria, held a group show, “Liminality in Infinite Spaces,” curated by Azu Nwagbogu, that featured twenty-three artists, part of a “new vanguard” of contemporary figuration across the African continent. Their work, the curatorial statement explained, “elevates the everyday experiences of Black and brown peoples” In December of the same year, Gallery 1957 staged “Collective Reflections: Contemporary African and Diasporic Expressions of a New Vanguard,” also a group show, with similar aspirations, showing sixty works by ten artists. Works of this nature — like those in “Homecoming” — pointedly do not have any didactic undertones and do not aspire to any “great” causes. They simply document Black people in states of leisure and rest — a much-needed addition to the history of contemporary portraiture.

Boafo, Botchway, and Quaicoe collectively hit the mark in this regard. But one can’t help wonder where their depiction of Blackness is rooted. Boafo and Botchway are based in Accra; Quaicoe lives in the United States. Boafo developed his career away from his home base, first garnering attention in Vienna, Austria, before traveling stateside and becoming a critical and commercial hit there. Botchway and Quaicoe’s careers are taking off in Europe and the US respectively.

The Blackness they depict does not make any strong suggestion of their Ghanaian heritage. Should it? The technique of centrally placing sitters in a frame with nothing around them, while inspiring a strong feeling of familiarity, also paradoxically imparts a sense of distance. There are no immediate markers suggesting where these people might be from, nor do the works immediately speak to any particular tradition of portraiture. In Quaicoe’s cowboy painting there’s an American sensibility of sorts. In Botchway’s painting mentioned earlier, no one in Ghana could comfortably dress like that because of the country’s year-round warm weather. Boafo’s sitters are even harder to place. All three painters have said they paint friends, strangers, people around them. One senses this is a deliberate choice, meant to realize on the canvas a Blackness that is “universal” or, perhaps, diasporic. But in the works of Kehinde Wiley, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, and even the American Kerry James Marshall, who these artists may count as predecessors and sources of inspiration, there’s a strong sense of place, history, and heritage of the sitters in the frame. Of course, this is not a requirement of any artwork necessarily. Freedom is essential to an artist’s creation. But it does invite inquiry as to who these paintings are for, and in what histories they are grounded.

The artistic choice to paint a subject within an empty void is a visually powerful one. Yet it calls to mind something Princeton professor and art historian Chika Okeke-Agulu once explained in an interview: “This is the problem of contemporary African artists. This has led some artists to create some distance between them and their cultural history because they feel it is tied too much to ‘African art’ that has not had enough respect amongst scholars and critics. [They believe] the more they distance themselves the more likely they will be appreciated as international contemporary artists.”

This is not an indictment of Boafo, Botchway, and Quaicoe’s choices. As their careers progress, however, it will be worth revisiting this description to see if it applies to their work.