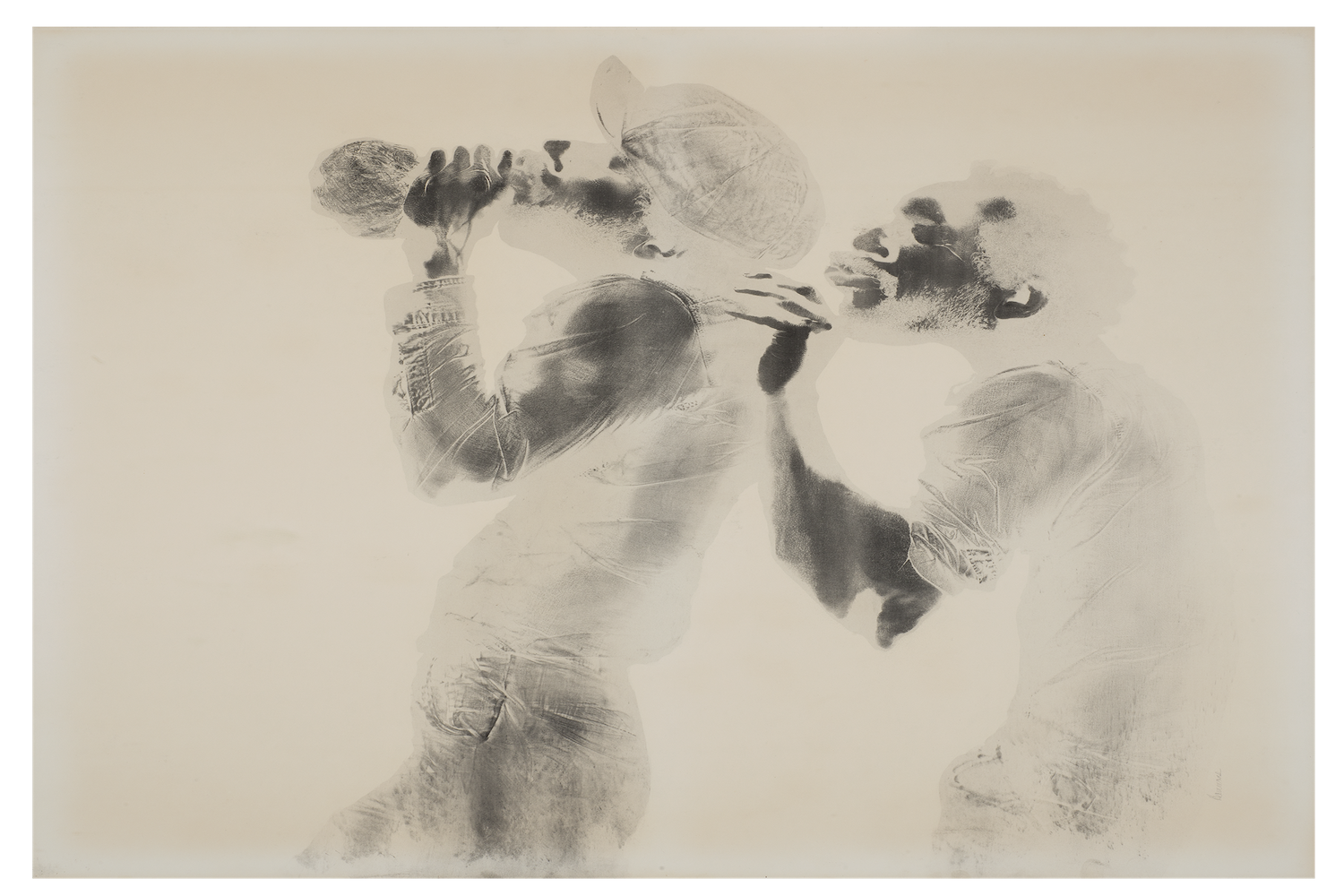

David Hammons, “Body Prints, 1968-1979”. Exhibition view at The Drawing Center, New York, 2021. Photography by Daniel Terna. Courtesy The Drawing Center, New York.

David Hammons, “Body Prints, 1968-1979”. Exhibition view at The Drawing Center, New York, 2021. Photography by Daniel Terna. Courtesy The Drawing Center, New York.

David Hammons, “Body Prints, 1968-1979”. Exhibition view at The Drawing Center, New York, 2021. Photography by Daniel Terna. Courtesy The Drawing Center, New York.

David Hammons, “Body Prints, 1968-1979”. Exhibition view at The Drawing Center, New York, 2021. Photography by Daniel Terna. Courtesy The Drawing Center, New York.

David Hammons, “Body Prints, 1968-1979”. Exhibition view at The Drawing Center, New York, 2021. Photography by Daniel Terna. Courtesy The Drawing Center, New York.

David Hammons, “Body Prints, 1968-1979”. Exhibition view at The Drawing Center, New York, 2021. Photography by Daniel Terna. Courtesy The Drawing Center, New York.

David Hammons, “Body Prints, 1968-1979”. Exhibition view at The Drawing Center, New York, 2021. Photography by Daniel Terna. Courtesy The Drawing Center, New York.

David Hammons, “Body Prints, 1968-1979”. Exhibition view at The Drawing Center, New York, 2021. Photography by Daniel Terna. Courtesy The Drawing Center, New York.

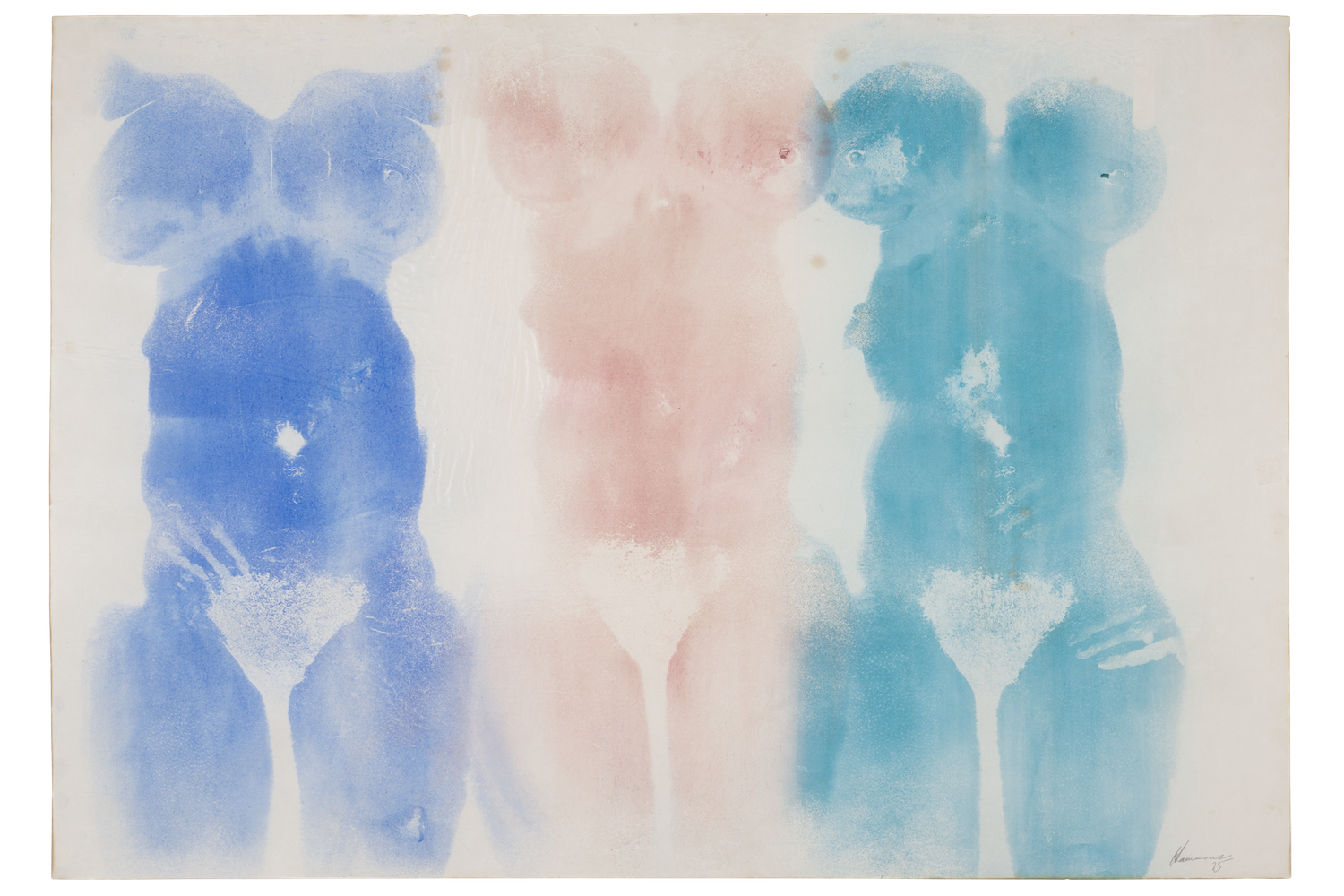

David Hammons’s “body prints,” his early works on paper, are a groundbreaking series that launched the artist’s career. The technique entails coating the body, typically the artist’s own, with a thin layer of grease and pressing it against a sheet of paper. The surface of the paper is then sprinkled with charcoal and powdered pigment. The level of precision is mind-boggling, with a resulting image that is somewhere between a photogram and an ectoplasmic apparition, a magical trick. The series was produced during the 1970s, a pivotal period for African Americans, particularly in California, where Hammons was living and working at the time. To fully comprehend its power, let’s refresh our memory with a few dates: in 1967, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party (BPP) for Self-Defense in Oakland, California; in 1969, the FBI murdered BPP member Fred Hampton in an attempt to crack down on the party; that same year, BPP founder Bobby Seale is refused a lawyer and is gagged and tied during his trial. Hammons refers to these events, sometimes directly through the titles of works, sometimes more obliquely by addressing the injustice and oppression imposed on Black bodies. The artist uses his own body to show how Black Americans are “framed” to be the recipient of American violence, the scapegoat on the altar of white supremacy, a prisoner within a political territory symbolized by the American flag — an authority that cannot be escaped, only painfully inhabited.

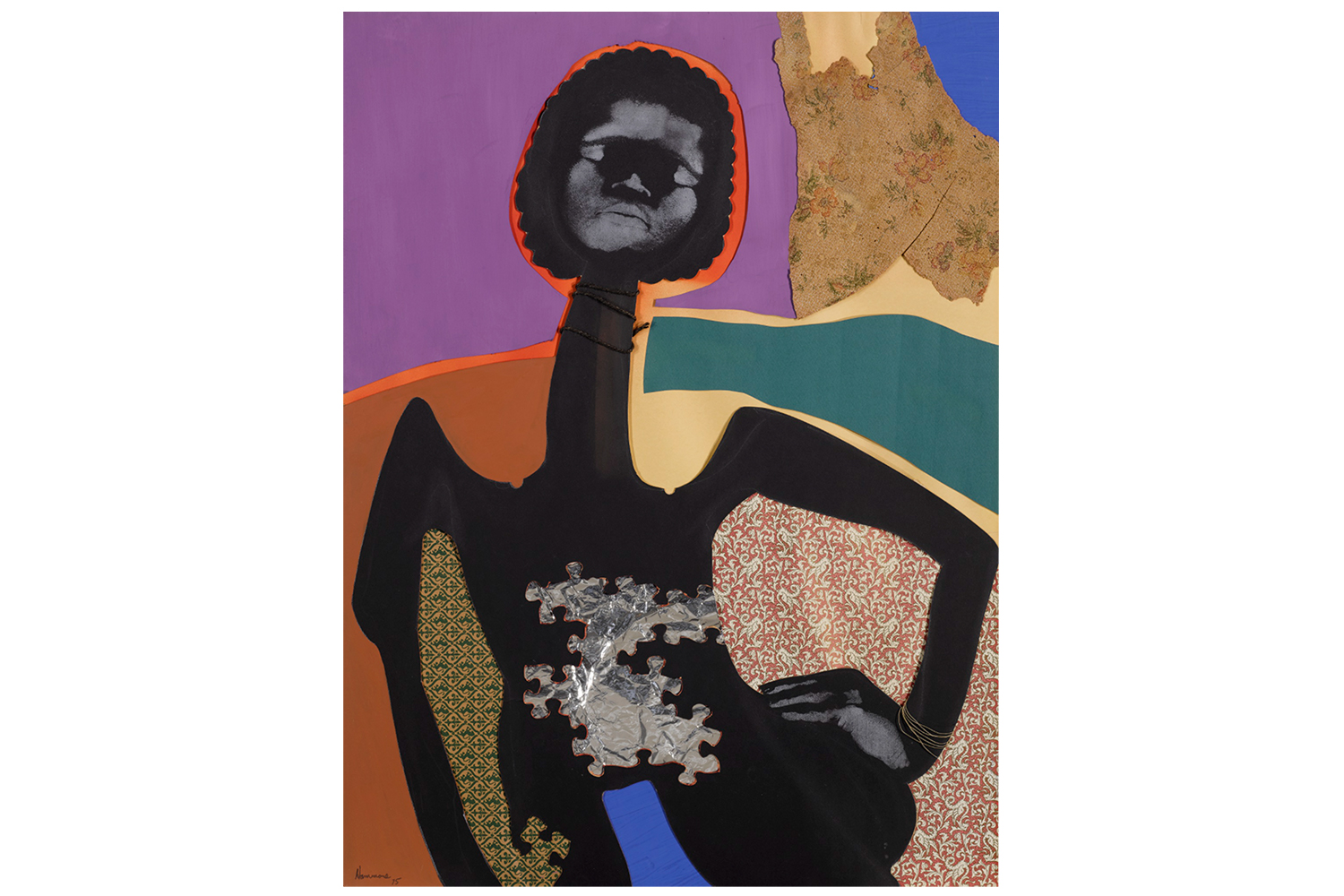

David Hammons, Untitled, 1975.

Grease, pigment and mixed media on paper on two sides. 104.1 x 78.7 cm.

Courtesy of Collection of Eleanor Heyman Propp.

David Hammons, Untitled, 1974. Grease and pigment on paper. 73.0 x

57.2 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

David Hammons, Untitled, 1974.

Grease and pigment on paper. 72.4 x 57.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist

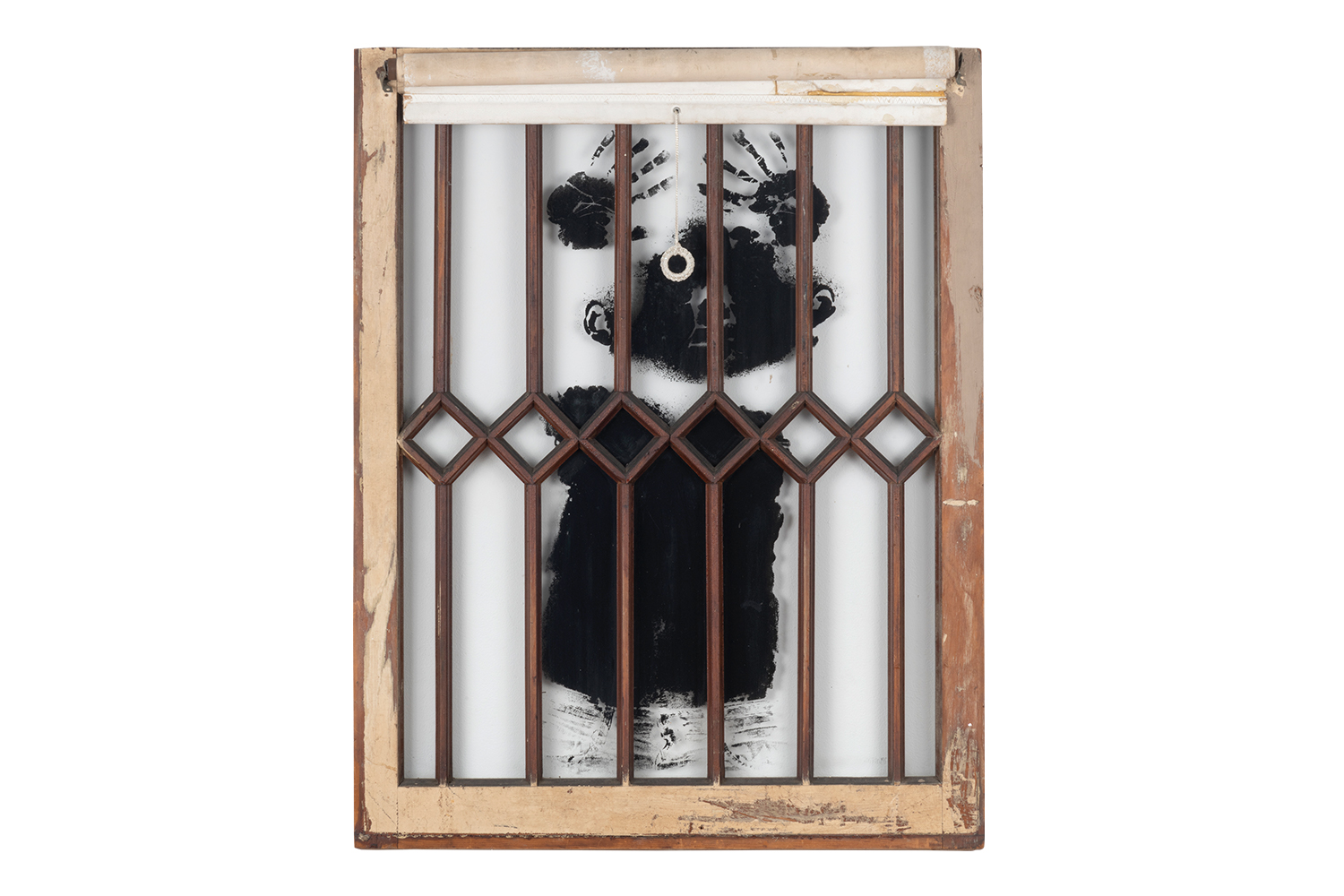

David Hammons, Black Boy’s Window, 1968.

Silkscreen on glass. 90.8 x 68.6 cm. Courtesy of Collection of Liz and Eric Lefkofsky.

David Hammons, Pray for America, 1969. Screenprint and pigment on paper. 153.7 × 76.2 cm.

Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York and The Studio Museum Harlem. Gift to The Museum of Modern Art and The Studio Museum in Harlem by the Hudgins Family in honor of David Rockefeller on his 100th birthday, 2015.

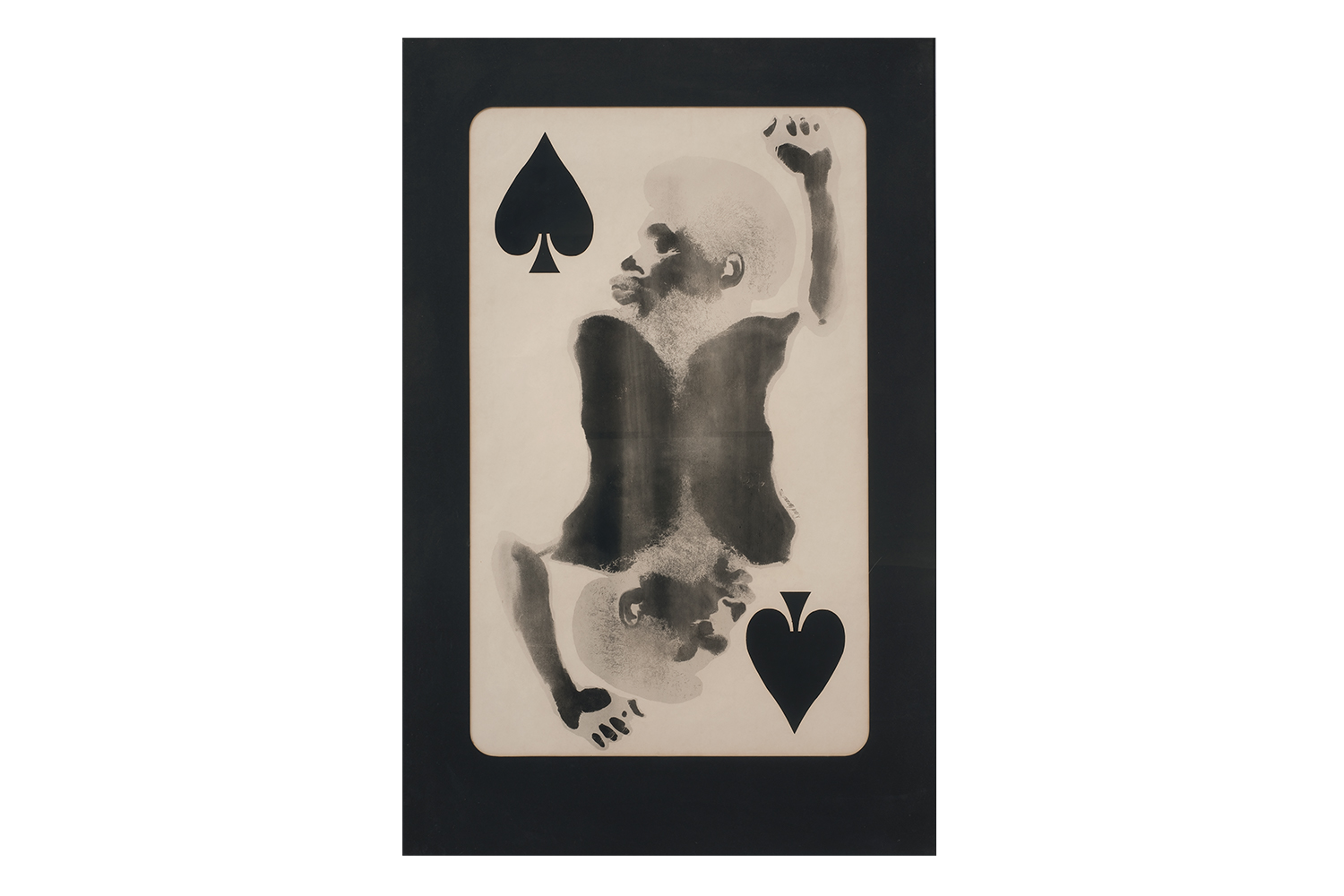

David Hammons, Spade (Power for the Spade), 1969. Grease, pigment, and silkscreen on

paper. 130.8 x 85.1

cm. Private Collection. Courtesy Tilton Gallery, New York.

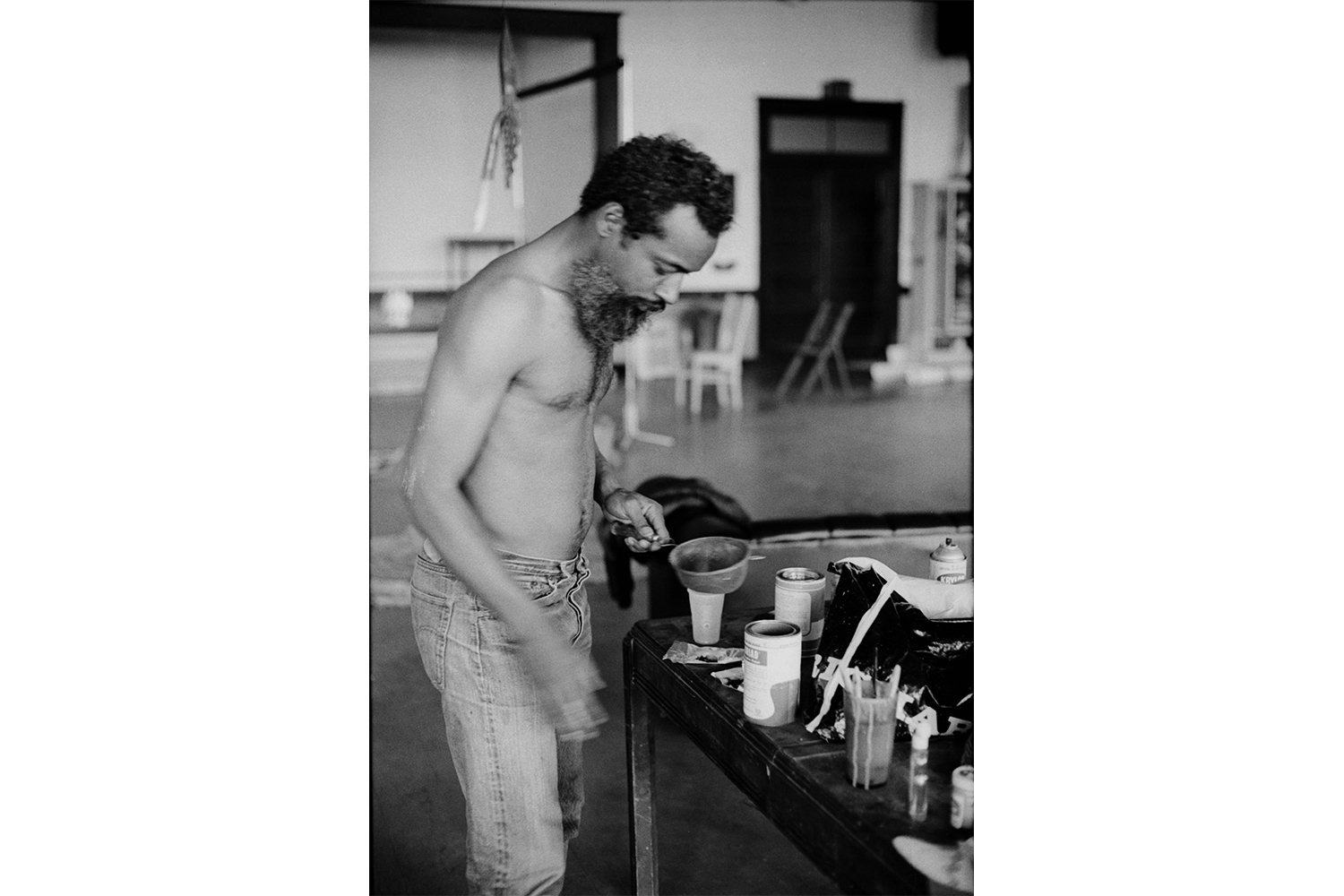

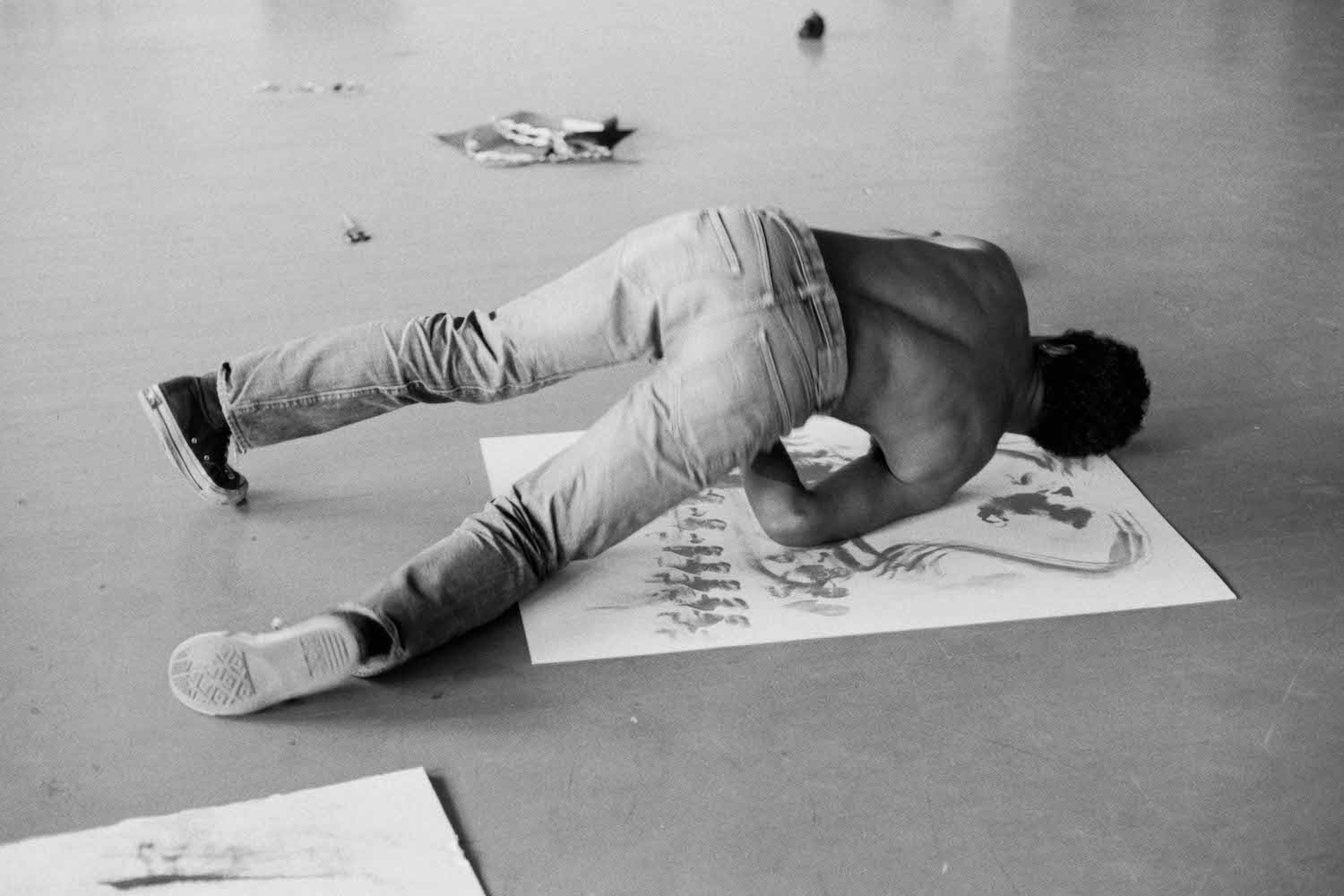

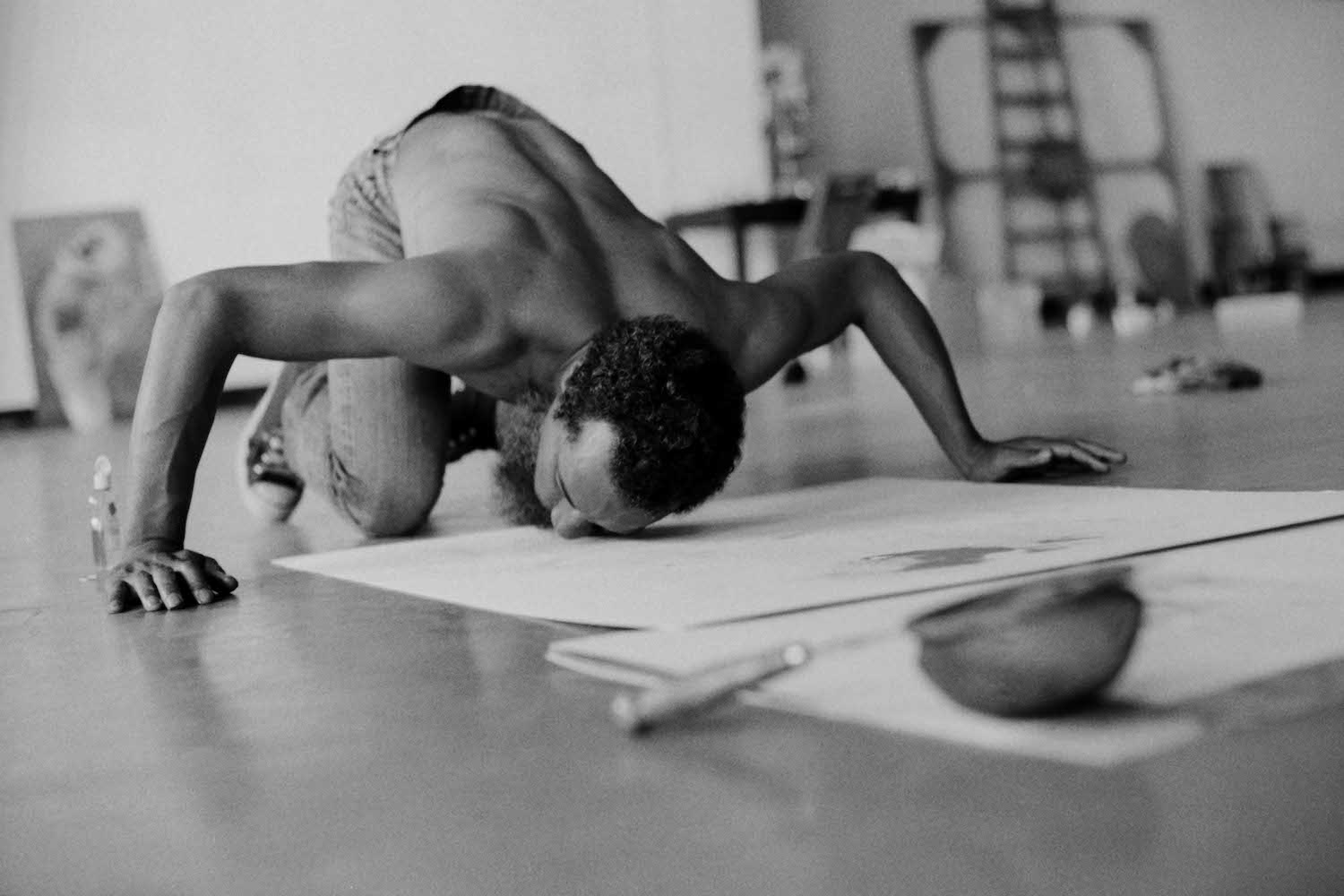

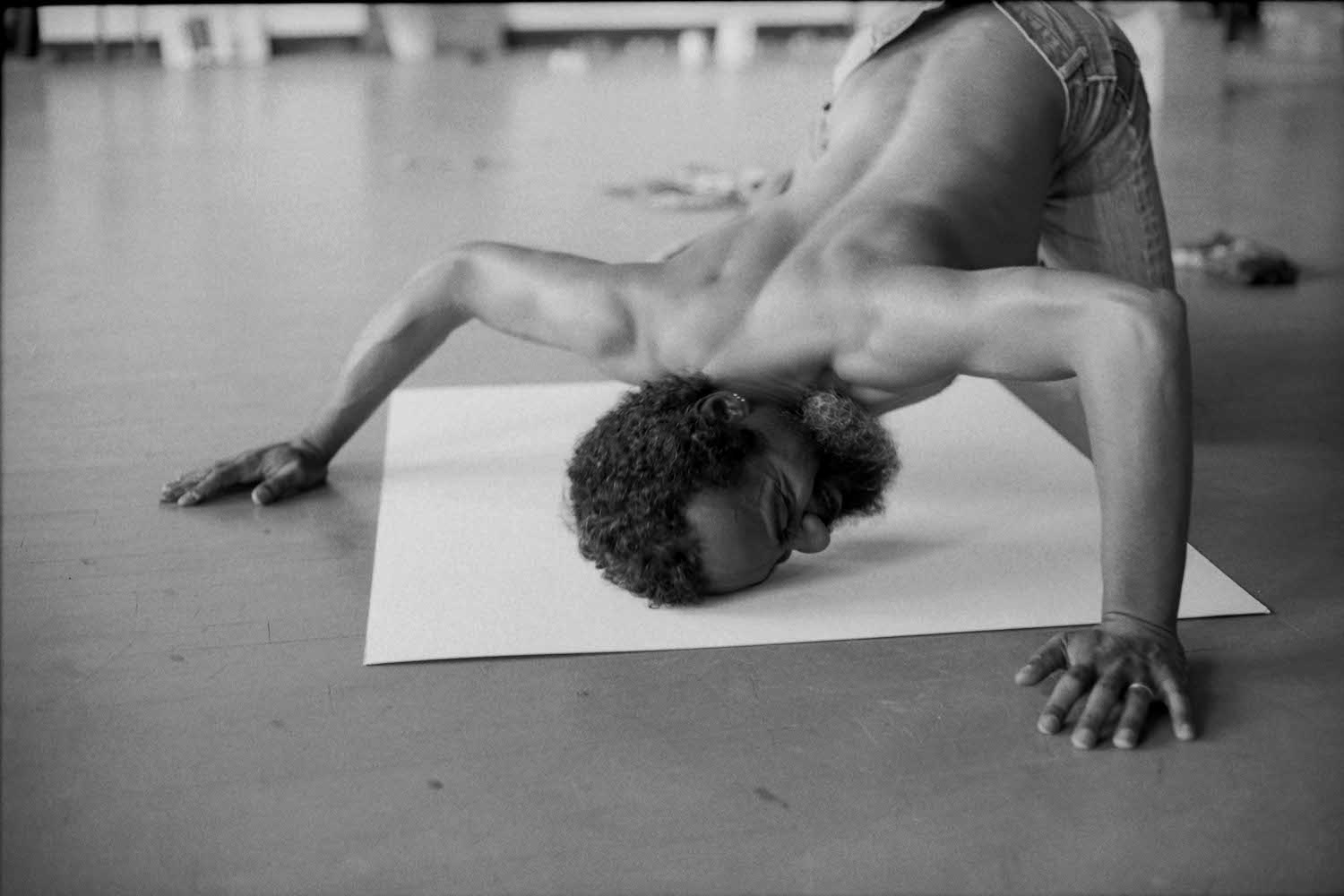

David Hammons making a body print, Slauson Avenue studio, Los Angeles, 1974

Digital silver gelatin print.

40.6 x 50.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

David Hammons making a body print, Slauson Avenue studio, Los Angeles, 1974.

Digital silver gelatin print. 40.6 x 50.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Hammons is an artist of absence, of the trace, of the invisible made visible. He invites viewers to connect the forensic dots in a political crime scene. He brings depth to the representation of the American Black body by excavating the stereotypes associated with it: The Wine Leading the Wine (c. 1969), Shine (1969), Spade (1969), etc. But rather than representations of victimhood, the works suggest a force that wants to break through, to break free. A figure’s eyes are shut — maybe for practical reasons, to keep grease out of them while making the print — helping convey excruciating pain, perhaps death. The series feels like a cemetery for all the warriors that fought for the flag’s ideals, but who were betrayed when the flag instead fought against them. The pressed bodies impart a sense of absolute rejection: a door closed on them forever, an existential, racist gate that cannot be crossed. Their skin is the reason they can’t pass through to a land of freedom and equality; they are trapped by their physical envelope.

David Hammons making a body print, Slauson Avenue studio, Los Angeles, 1974.

Digital silver gelatin print, 40.6 x 50.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

David Hammons making a body print, Slauson Avenue studio, Los Angeles, 1974.

Digital silver gelatin print. 40.6 x 50.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

David Hammons making a body print, Slauson Avenue studio, Los Angeles, 1974.

Digital silver gelatin print. 40.6 x 50.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

David Hammons and Bruce Talamon Self Portrait, La Salle Street studio, Los Angeles, 1977.

Digital silver gelatin print. 40.6 x 50.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Untitled (Man with Flag), n.d.

Grease, pigment, and white crayon

on paper

29 3/4 x 39 3/4 inches (75.6 x 101 cm)

Glenstone Museum, Potomac,

Maryland

Photograph by Alex Jamison,

courtesy of Mnuchin Gallery, New

York

David Hammons, Bye-Centennial, 1976.

Grease and pigment on paper. 48.3 x 61 cm. Photography by Bruce M. White. Courtesy of Collection of Lonti Ebers, New York.

David Hammons, Untitled, 1975.

Grease and pigment on paper. 76.8 x 101 cm. Courtesy of Hudgins Family Collection, New

York.

David Hammons, The Wine Leading the Wine, c. 1969.

Grease and pigment on paper. 101.6 x 121.9 cm.

Courtesy of Hudgins Family Collection, New

York.

Yves Klein may have been the first to explore body painting, but the power of Hammons’s body prints takes the viewer to a place far from Klein’s sensual dance. Spade (Power for the Spade) (1969) and Black First, America Second (1970) have a spectral quality, a miraculous precision that, fifty years later, is reminiscent of the shroud of Christ, whose blood and sweat provided the ingredients for a stunning resolution. I see these body prints as confrontations with the two-dimensional; they depict a struggle for a third dimension, a human dimension, a civic dimension. The subject tries to transubstantiate, passing through his skin and his sociocultural status where he is restrained by white society. He is hitting a glass ceiling, trying to find the exit, grasping for air, pushing back against his oppressor — a fight and a dance that still resonate today.