“The Uncanny Valley” is Flash Art’s new digital column offering a window on the developing field of artificial intelligence and its relationship to contemporary art.

Everyone gets it wrong from time to time. We live lives we would like to control, but that every so often get out of hand. Accidents beget disappointments, but it’s the fear of making a mistake that hurts us most. Many grow up with the idea that mistakes belittle us — place us in a position below those around us — and must therefore be avoided. This is a shortsighted perspective that ignores another reality whereby failure creates opportunity.

Art and technology are intertwining more and more, giving life to works that are technically advanced and conceptually interesting. Their entanglement not only brings us into critical contact with the latest technological developments but allows us to grasp more complex aspects of the human condition when met with a world of machines. The cultural studies critic John Berger once said: “At times failure is very necessary for the artist. It reminds him that failure is not the ultimate disaster. And this reminder liberates him from the mean fussing of perfectionism.” Glitch art facilitates this very embrace of failure in its various facets and translates it into a context beyond the purely artistic.

The etymology of glitch seems to originate from gletshn (a Yiddish word meaning “to slide or skid”) and glitschen (a German word meaning “to slip”). A glitch indicates a temporary and sudden malfunction that is frequently found in video games, electronic and computing systems, and circuit bending. In the 1990s, the term was first associated with a genre of experimental electronic music that featured sounds derived from malfunctions in analog or digital audio recording, such as system errors, distortions, hardware noise, software bugs, etc. Later, the glitch style, taken up in the work of many veejays (VJs) and visual artists, went on to indicate an artistic movement within digital art that was widely recognized at the GLI.TC/H conference, the first international assembly of noise and new media artists held in Chicago in 2010.

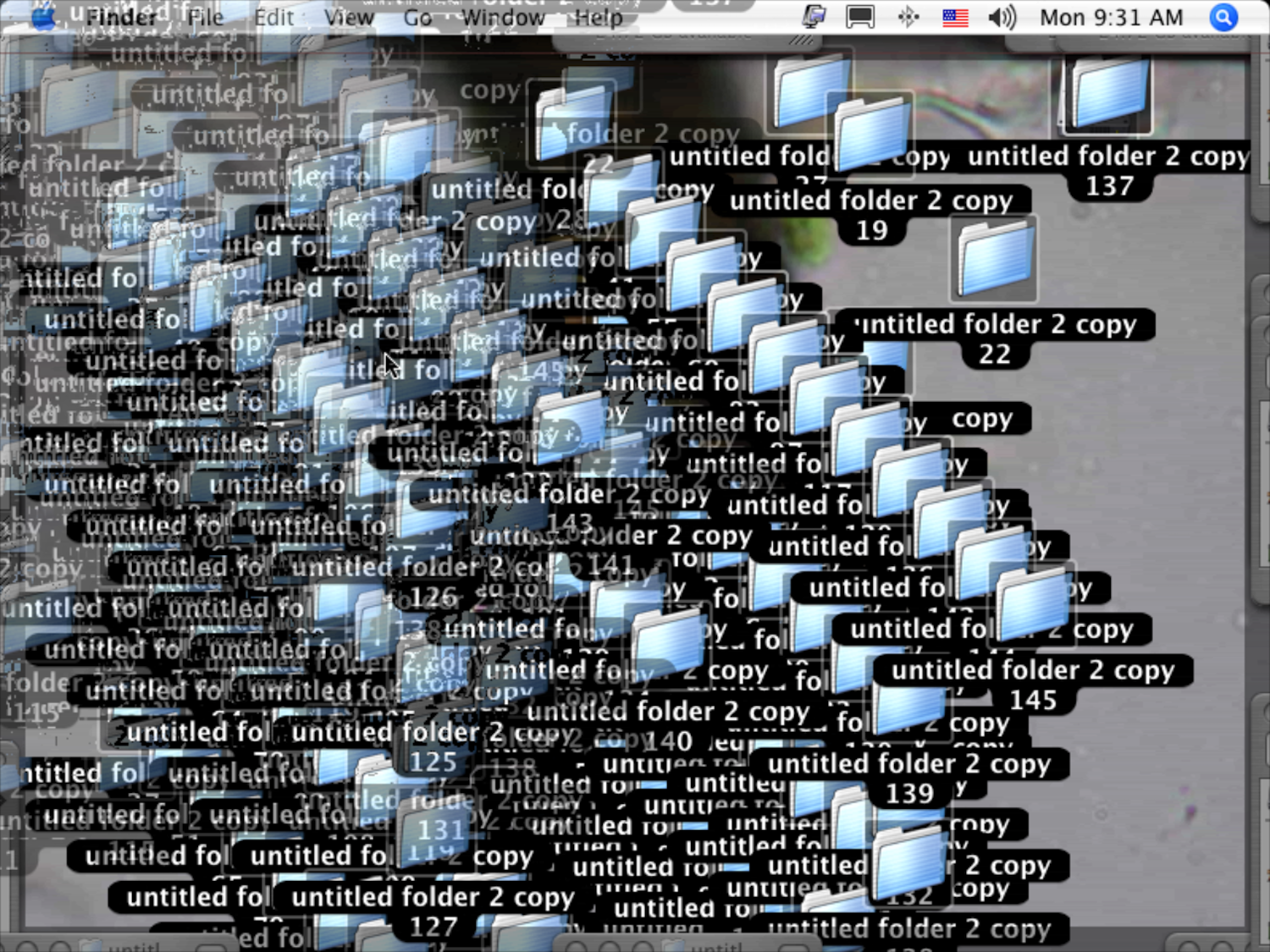

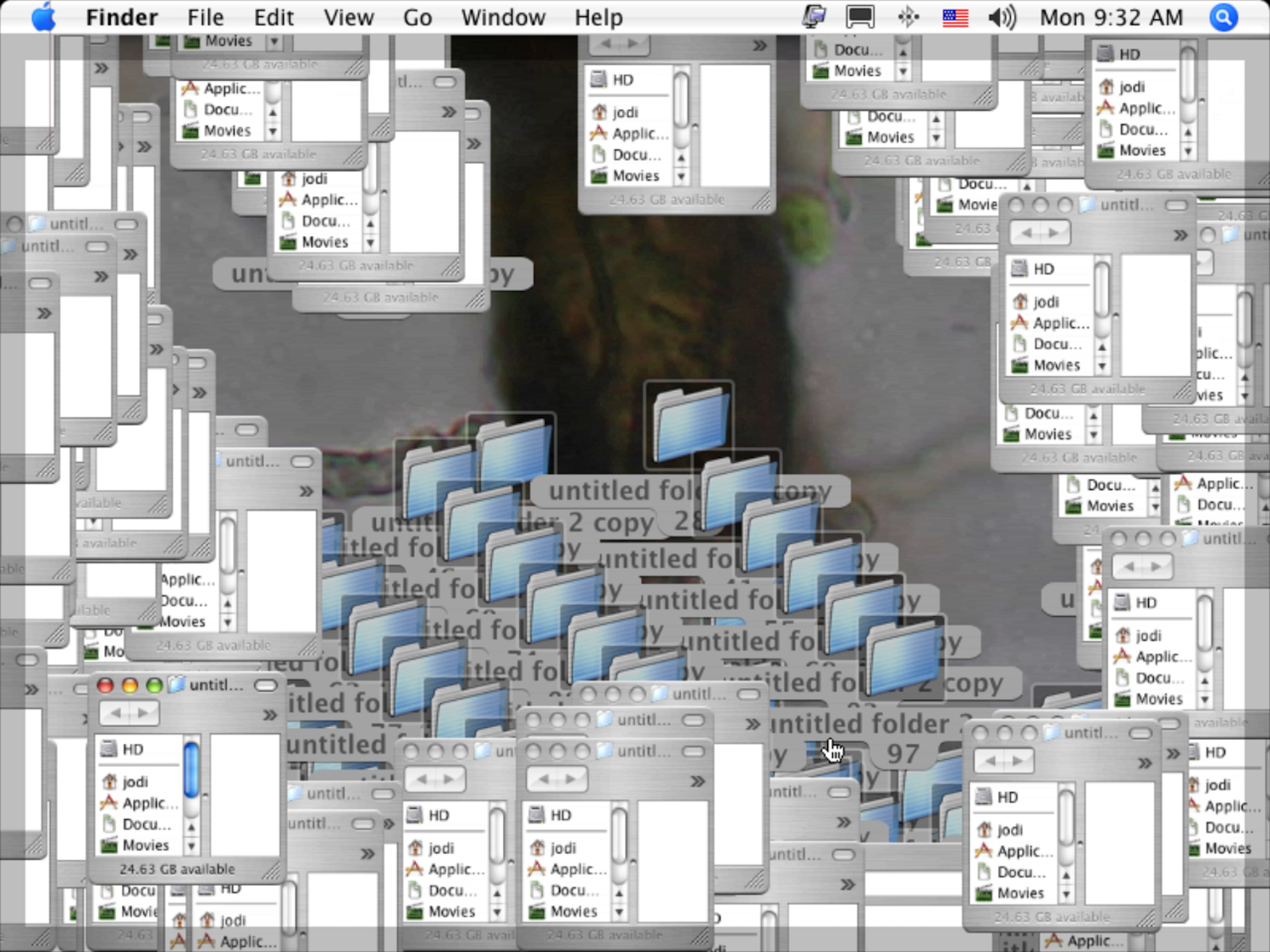

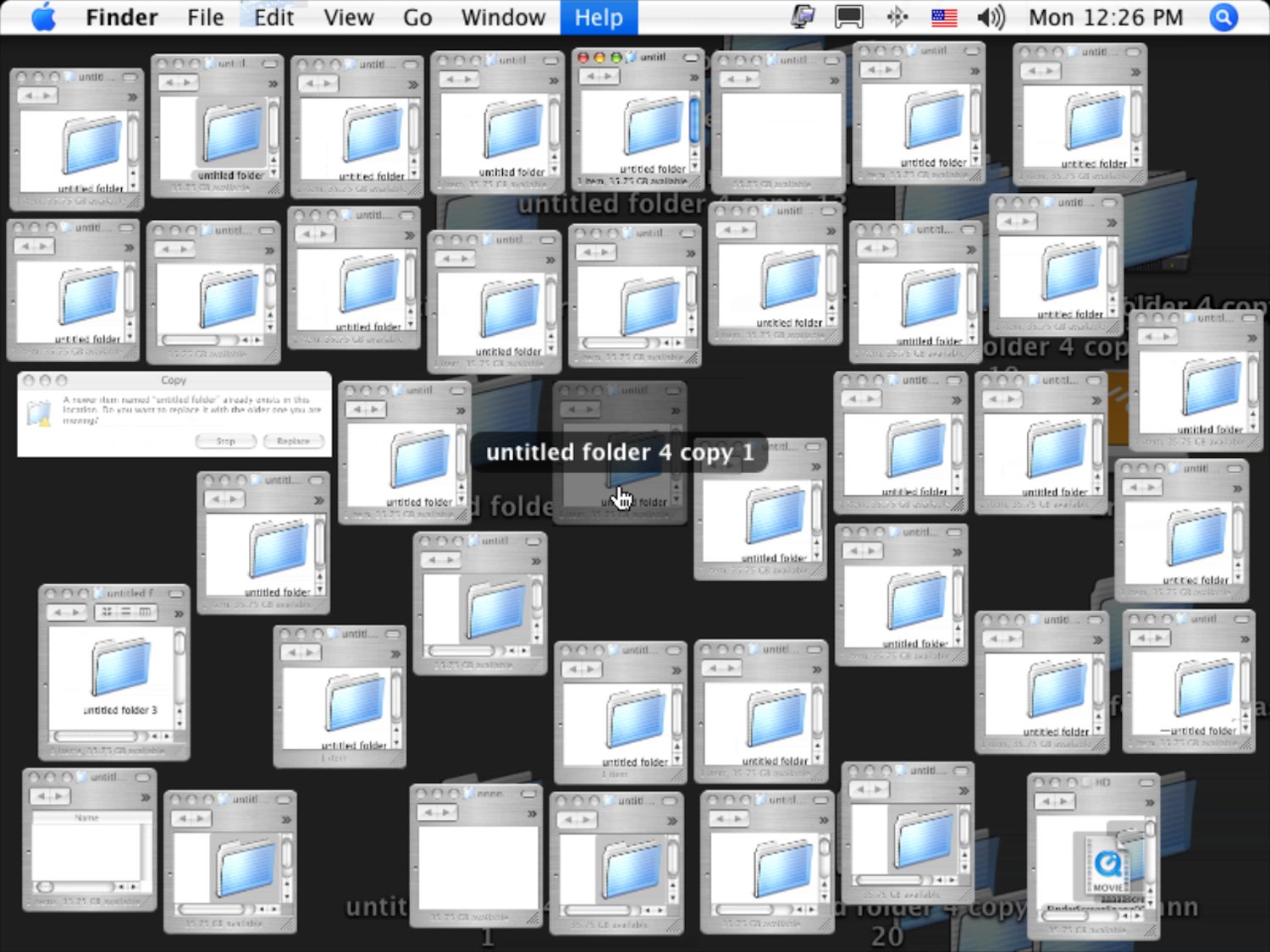

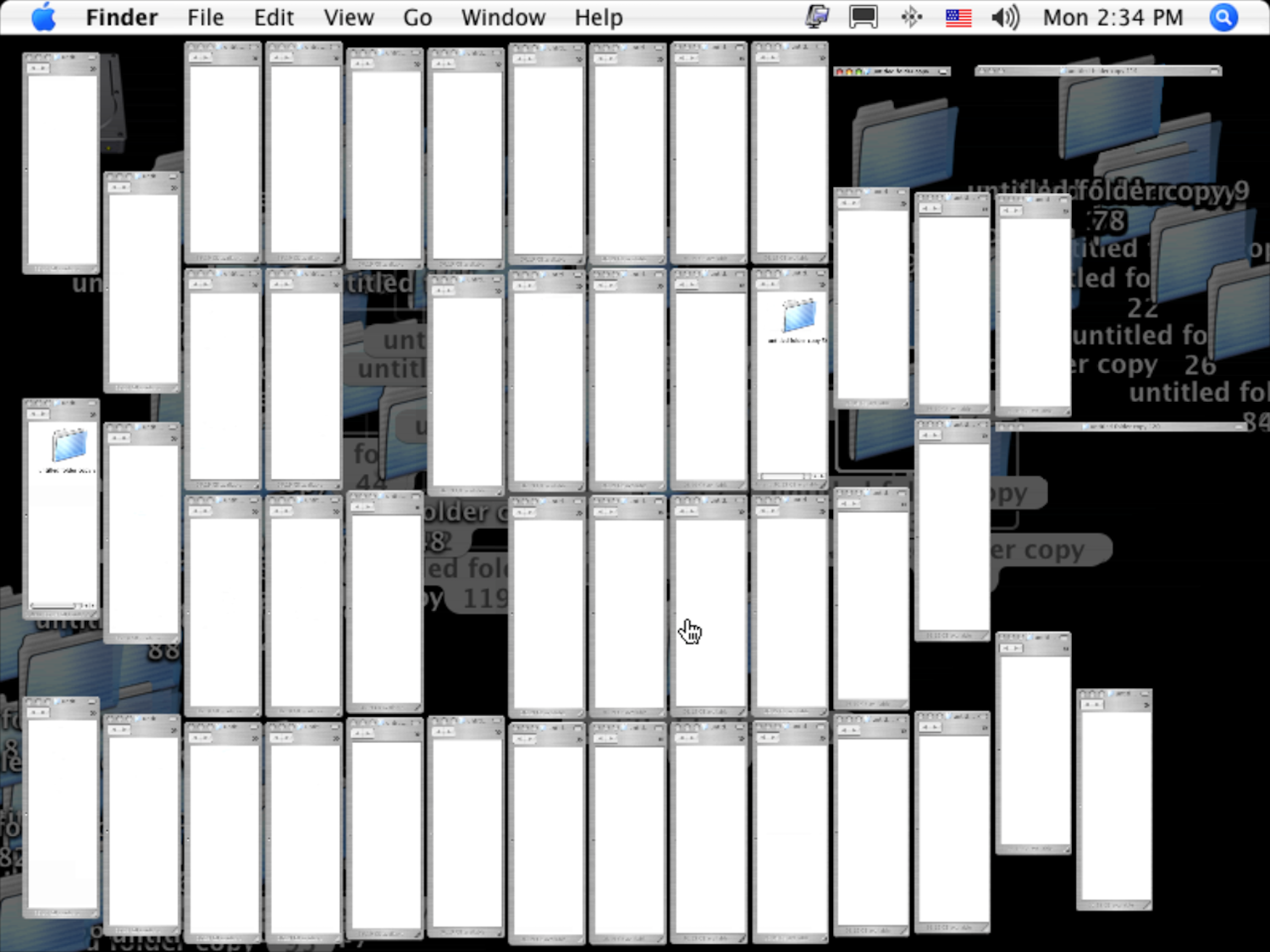

Glitch music was notable for its so-called aesthetic of failure, the result of a deliberate use of accidents and flaws in its creation. This aesthetic was soon extended beyond the musical domain, appearing in both theoretical and practical works that promoted failure not only as a means of creation but also as a prompt for reflection on our relationship with technology. The JODI collective, whose works range from web art to software art to artistic computer game modification, were among the first to use computer error aesthetics to bring out the mechanisms of the web, thus transforming an (apparent) system failure into an epiphany. One example is their maze-like website — a work of art in itself — where the deliberate introduction of errors in the HTML language has brought to light invisible functionalities within the digital system. In their pioneering work, which is a precursor to Net art and positions itself between experimentation and hacking, JODI cultivates errors and glitches to provide viewers with alternative aesthetics and critical ways to deal withtechnology. Their work My%Desktop (2002) joined the permanent collection of MoMA at the end of 2019. It consists of four projections that present screenshots of “desktop performances.” My%Desktop, of which there are several live recordings, is an investigation into irrational human behavior triggered by the inundation of online data and by the possibility of “play” with the system. Erratic user behavior manifests itself as a computer glitch.

In her article “The Aesthetic of Failure: Net Art Gone Wrong” (2002), Michele White defines the new aesthetic as “the ways that net artists reflexively quote and misuse the programmed aspects of the computer.” In her view, this aesthetic is the result of a specific kind of spectatorship. The modalities with which net artists work can lead to a detached observation of the mechanisms and language of the internet. Thus unfolds a new type of spectator who resists traditional “spectatorial mastery,” who is forced to confront an artistic object that is difficult to control and interact with. Electronic music composer Kim Cascone, author of “The Aesthetics of Failure: ‘Post-Digital’ Tendencies in Contemporary Computer Music” (2000), identifies “failure” as a nascent aesthetic trend toward the end of the twentieth century. Inspired by Nicholas Negroponte, who in 1998 prophesied the end of the digital revolution, Cascone suggests that the emergence of a post-digital aesthetic must be sought through the experience of working in environments pervaded by technology combined with the malfunction of technology itself. Musicians and composers, concerned with exploring the new, began to isolate noises produced by printers, computer fans, hard drives as well as system crashes and software bugs, and to use them as raw material for new works. This led Cascone to affirm that in glitch music “the medium is no longer the message; the tool has become the message.”

Glitch art moves these ideas forward. Based on the visual aspect of technical faults, it revolves around the use of both analog and digital errors obtained by physically altering electronic devices or corrupting digital data. To produce glitches, artists may adopt several techniques, including databending, datamoshing, circuit bending, and hardware malfunction.

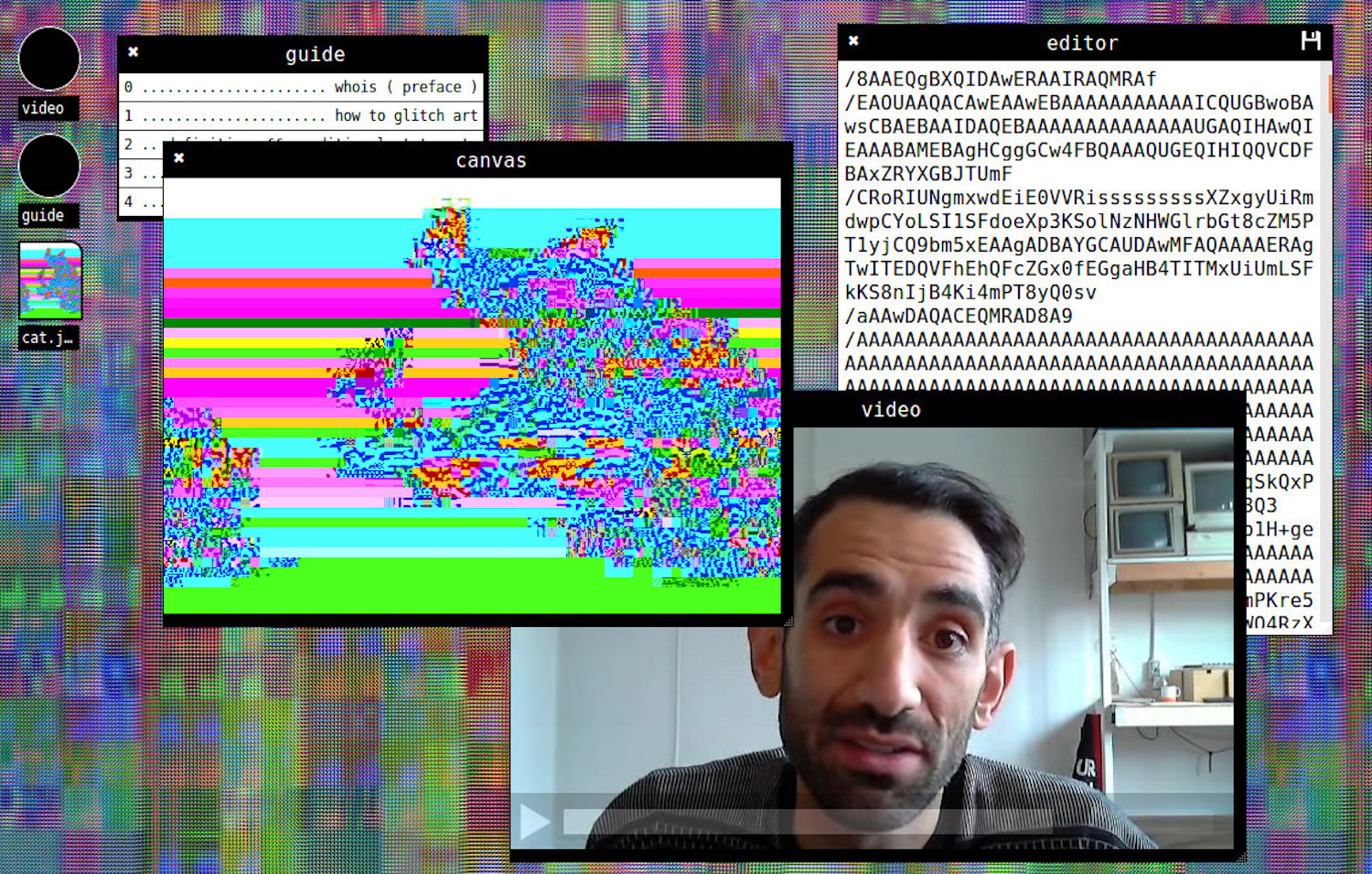

In his hypermedia essay “Thoughts on Glitch[Art]v2.0” (2015), Chicago-based internet artist, organizer, and educator Nick Briz labels the glitch as “an unexpected moment in a system that calls attention to that system,” rather than considering it an error. A glitch is something that takes us by surprise but is not the result of a system malfunction, since the computer will have produced correct results for the instructions received. Briz emphasizes the importance of not confusing a glitch artifact or aesthetic — which is subject to technological changes over time — with the “act of glitching.” Discussing its nature in depth, he sees the glitch as something that occurs unexpectedly, and glitch art as an ethic, understood not in a moral sense but “as a set of principles for practice in accordance with some convention.”

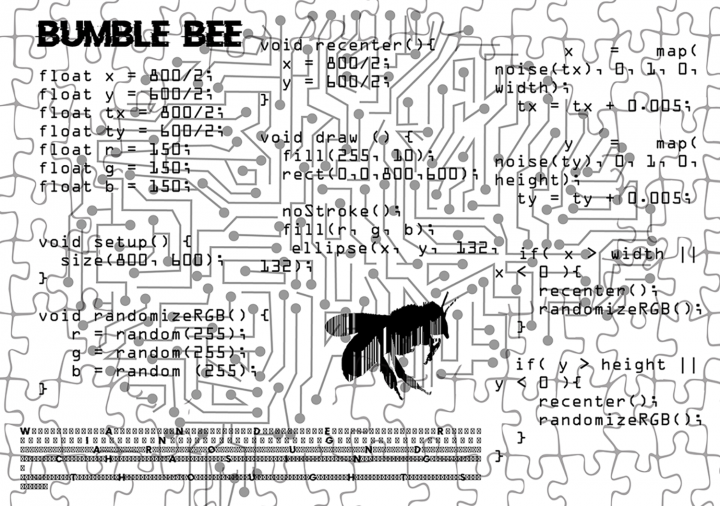

The glitch ethic is “about consciously doing things the wrong way.” Briz starts from the idea that technology is not neutral, but undermined by the one-sided vision of its creator. For artists, it is a matter of choosing whether to reject the ideologies and pre-established functions of digital systems in the name of freedom, or whether to adjust to them and thus use technology in the way their creators prescribed. Shifting the focus from the artifact and its aesthetic to a process and its methodology, Briz transforms the glitch into a political tool for challenging conventions, leading users and viewers to a more conscious interaction with machines. This idea is discussed in Briz’s essay Glitch Codec Tutorial (2010–11), which explores not only theoretical and technical aspects related to glitch art but also an approach (through glitch art as a process) that protests against technology understood as a set of imposed political and cultural forces. This sheds light on works such as the well-known video artwork Apple Computers (2013), described by VICE as “a powerful affront against Apple and a manifesto for the prosumer of our age.” Originally made for an event curated by Dirty New Media artist and academic Jon Cates, called REMIX-IT-RIGHT: Rediscoveries in the Phil Morton Archive, Briz’s work takes up topicsinspired by the previous work of video artist and activist Phil Morton, such as “technological self-reliance, control and copying.” It then shifts to specific issues concerning Apple and the Information Age, such as “planned obsolescence” and “upgrade culture.” The work borrows Morton’s video style and is enriched by the hallmark of the Chicago new media scene: a mix of glitch and what Briz calls “prepared desktop” aesthetics.

New York–based artist Daniel Temkin approaches glitch art in more philosophical terms. In his essay “Glitch && Human/Computer Interaction” (2014) for NOOART: The Journal of Objectless Art, he argues that “glitch art mythologizes the computer error as its ultimate muse and most potent tool: the event that triggers each piece to manifest.” Speaking with DJ Pangburn of Vice Motherboard, he points out how the focus on computer error distracts from much more compelling questions about the relationship of humans with technology and logic systems. The artist considers glitch art a form of “demented” algorithmic art, which he calls demented algo-glitch. This is because the glitch is very often obtained through the introduction of corrupted and distorted data (i.e. noisy data) or the improper use of algorithms that are not used for the purpose for which they were designed. An example provided by Temkin is to open a JPEG image with a text editor, thus corrupting and visually abstracting it through software malfunction. This modus operandi is in contrast to traditional algorithmic art, a niche within generative art, in which conventional use of algorithms produces a visual artifact.

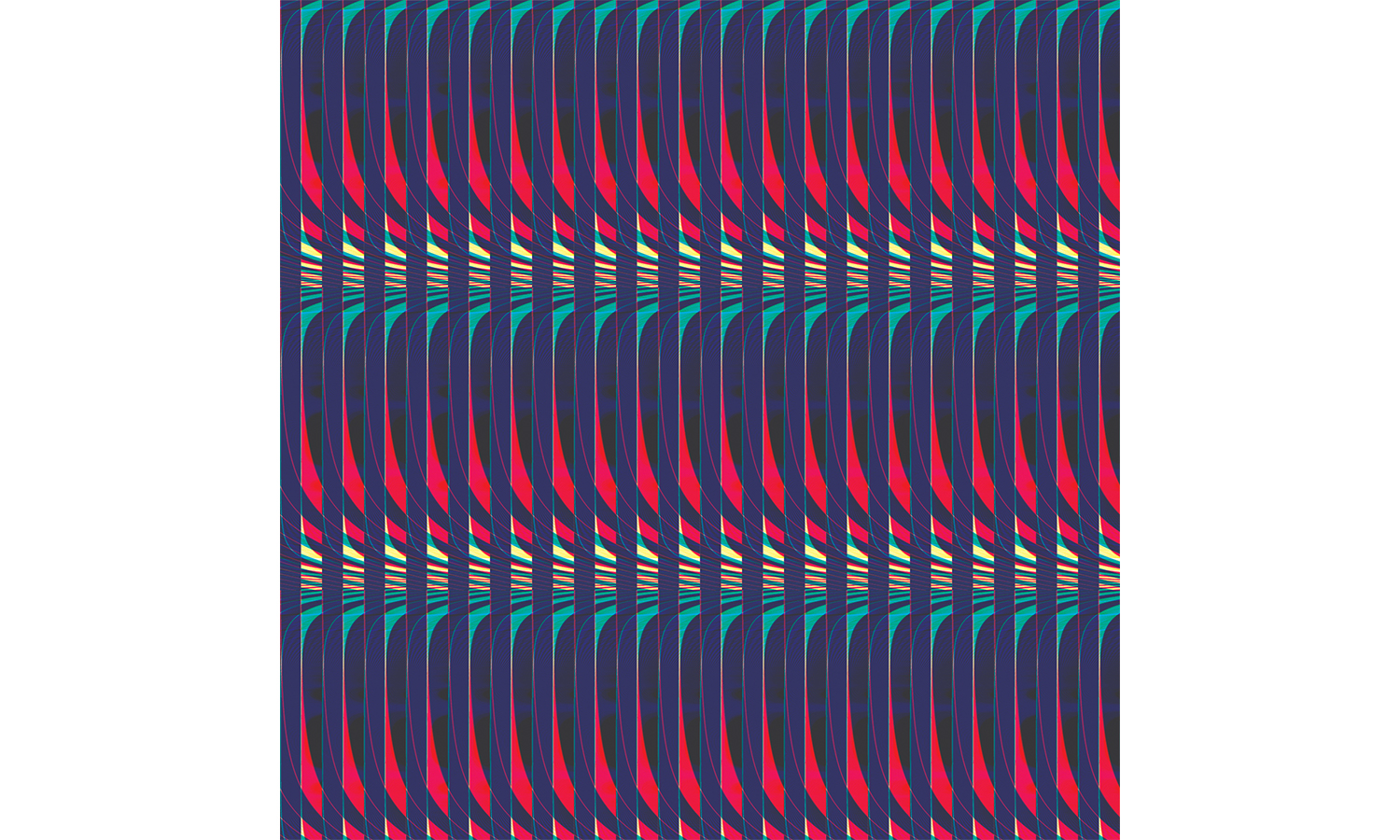

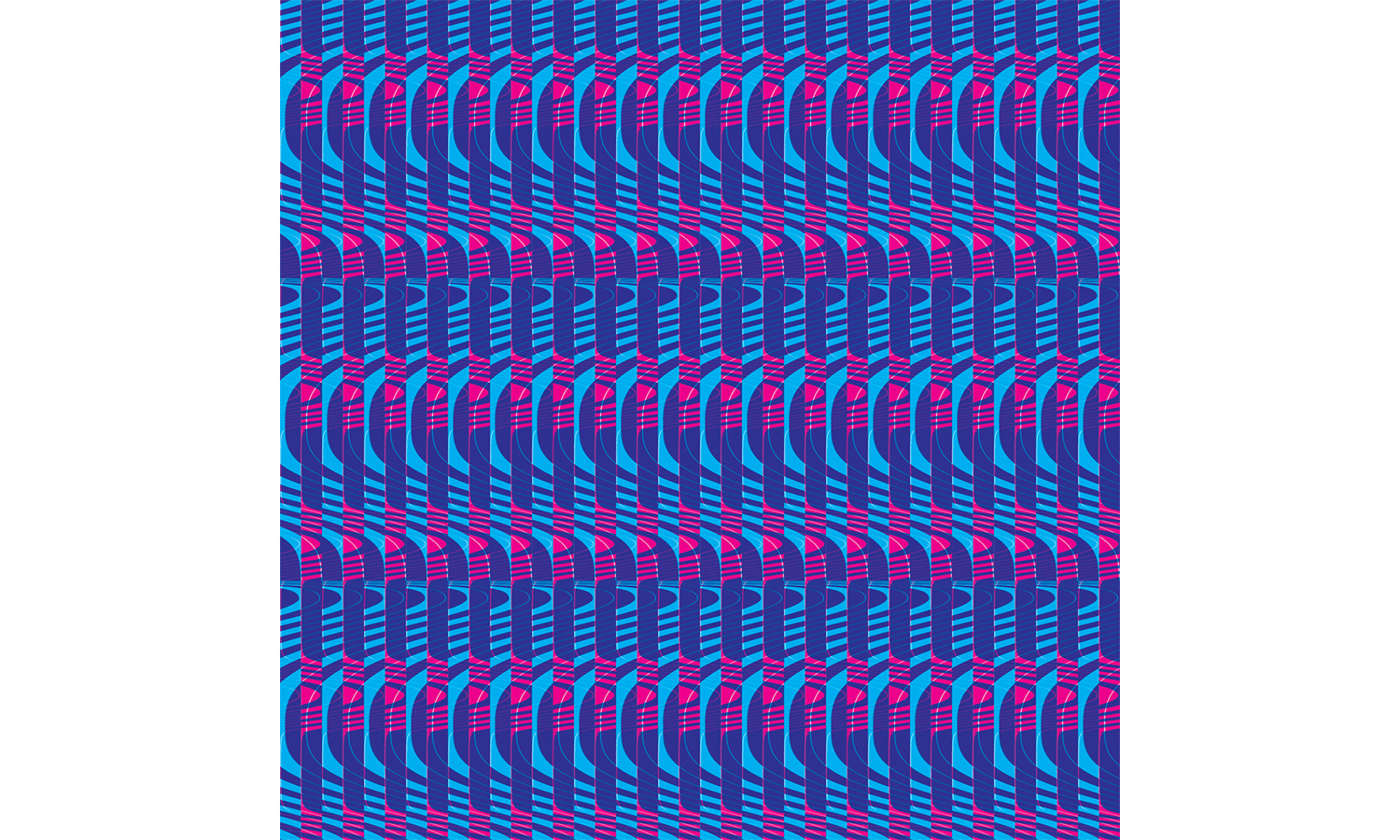

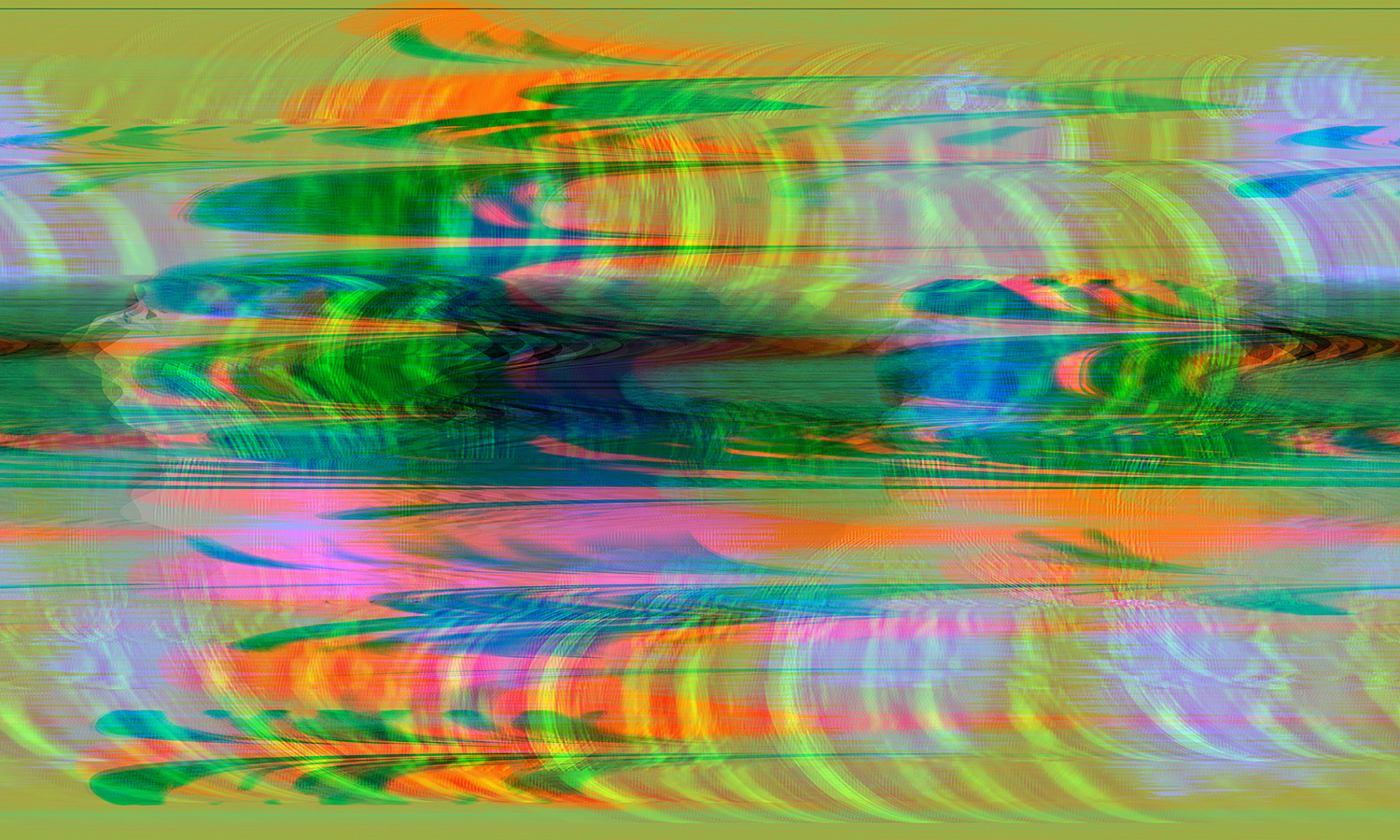

According to Temkin, once the conceptual limit of error has been exceeded, glitch art would serve to comprehend othermatters. For example, we may gain a greater understanding of the collision between “systemic logic” and “human irrationality,” or the function of software that “fails to fail completely” when faced with unexpected data, or the unease that comes from losing control over the process. In Glitchometry (2011–ongoing) the artist starts with black geometrical shapes, such as circles or squares, which are imported into an audio editor. From there, the images undergo a process called sonification, by which they are corrupted through the application of sound algorithms. Visual data are edited, altered, and modified by tools designed for sound. The final result is a series of c-prints that show the original images, completely distorted by the process, as colorful sound waves. This work not only investigates the practice of databending, that is, the manipulation of files of a specific format with software destined for a different one, but also the aspect of control over the final result, which is left to the logic of the machine. Glitchometry Stripes (2013/2016), which is an extension of Glitchometry, shows more graphic results as well as the influence of Op art. The starting point is always from black-and-white figures (stripes) that go through a sonification process using simpler sound effects.

The critique of digital capitalism and a persistent tension between chaos and control, destruction and re-creation, are among the elements that make glitch art more than a mere style. In her book The Glitch Moment(um) (2011), Dutch artist Rosa Menkman admits that framing the concept of glitch is difficult due to its dependence on the spectator’s “technical, aesthetic, and theoretic literacy.” In “The Glitch Art Genre,” a short text published on the platform O Fluxo, she explains:

While technological glitch is primarily a process of shock requiring investigation and cognition, glitch art is best described as a collection of forms and events that oscillate between extremes: the fragile, technologically based moment(um) of a material break, the conceptual or techno-cultural investigation of breakages, and the accepted and standardised commodity that a glitch can become.

Therefore, the glitch is something that oscillates between process and artifact, while glitch art is a genre “with a very decentralized essence” that presents a wide variety of works dealing with the most disparate topics. For Menkman, the different glitching trends share the common trait of being interruptions of flows, configurable both as human expectations toward the system and as common work processes of the system itself. She stresses the fact that there is no computing error since the computer carries out the orders given. Rather, it is a lack of understanding between man and machine, a failure of working together. The aesthetic of the glitch reveals the intrinsic mechanisms of a digital environment — a fleeting moment in which the interruption of fluidity becomes a symbol of new awareness and possibility of choice.

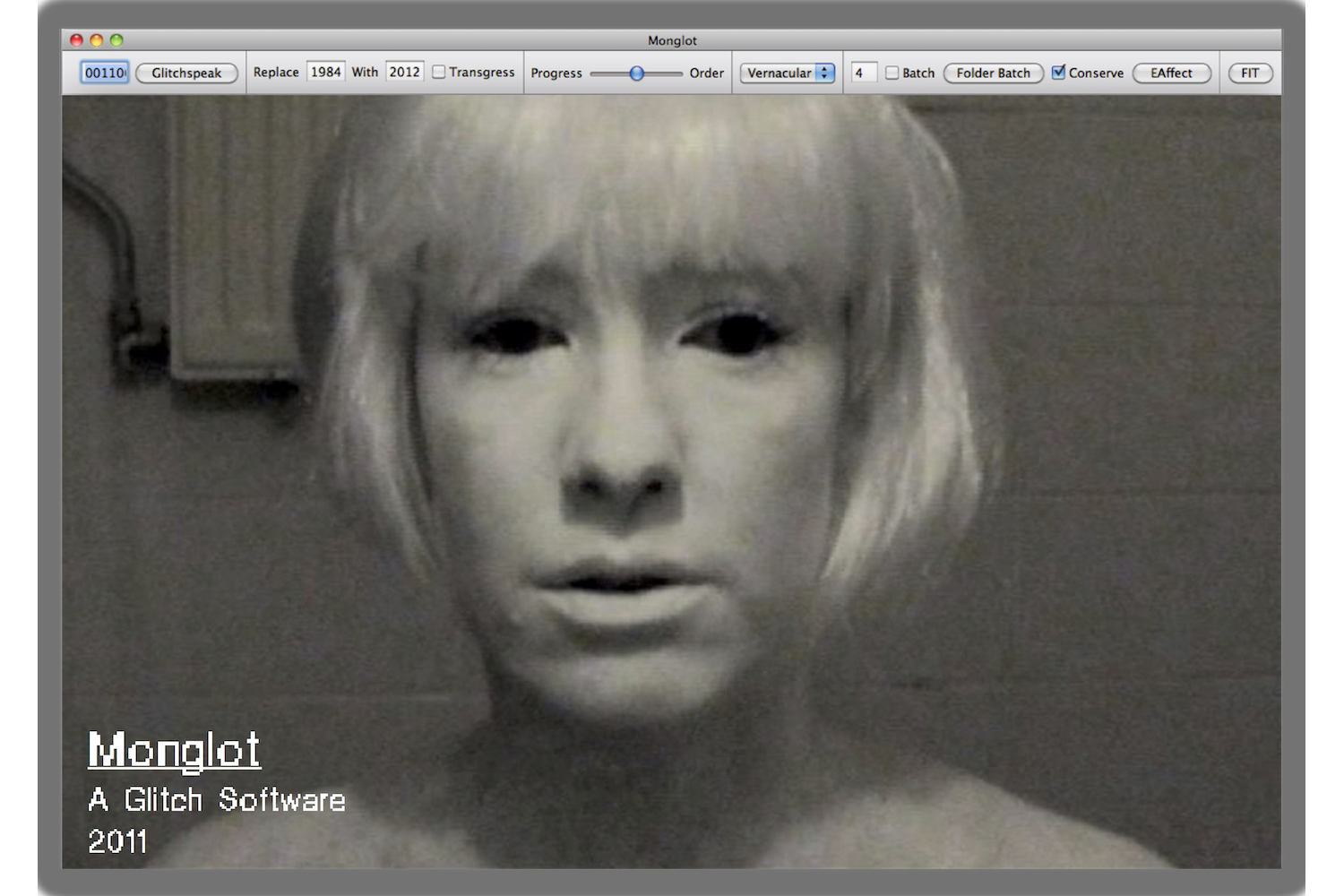

In “Order and Progress” (2011), Menkman’s solo show at the Fabio Paris Art Gallery in Brescia, Italy, curated by contemporary art critic Domenico Quaranta, the glitch is explored in its different values. The exhibition included four works: The Collapse of PAL (2010), A Vernacular of File Formats (2009–10), Monglot (2011), and Dear mr. Compression (2010), accompanied by text written by the curator. The title ironically echoes the principle that guides technological development, which the artist interrogates through the use of flaws, compressions, distortions, feedback loops, and so on. While the glitches maintain a positive value, they also are tinged with cultural, metaphorical, and political overtones. Menkman embraces the words of Paul Virilio: “The accident doesn’t equal failure, but instead erects a new significant state, which would otherwise not have been possible to perceive and that can ‘reveal something absolutely necessary to knowledge.’”

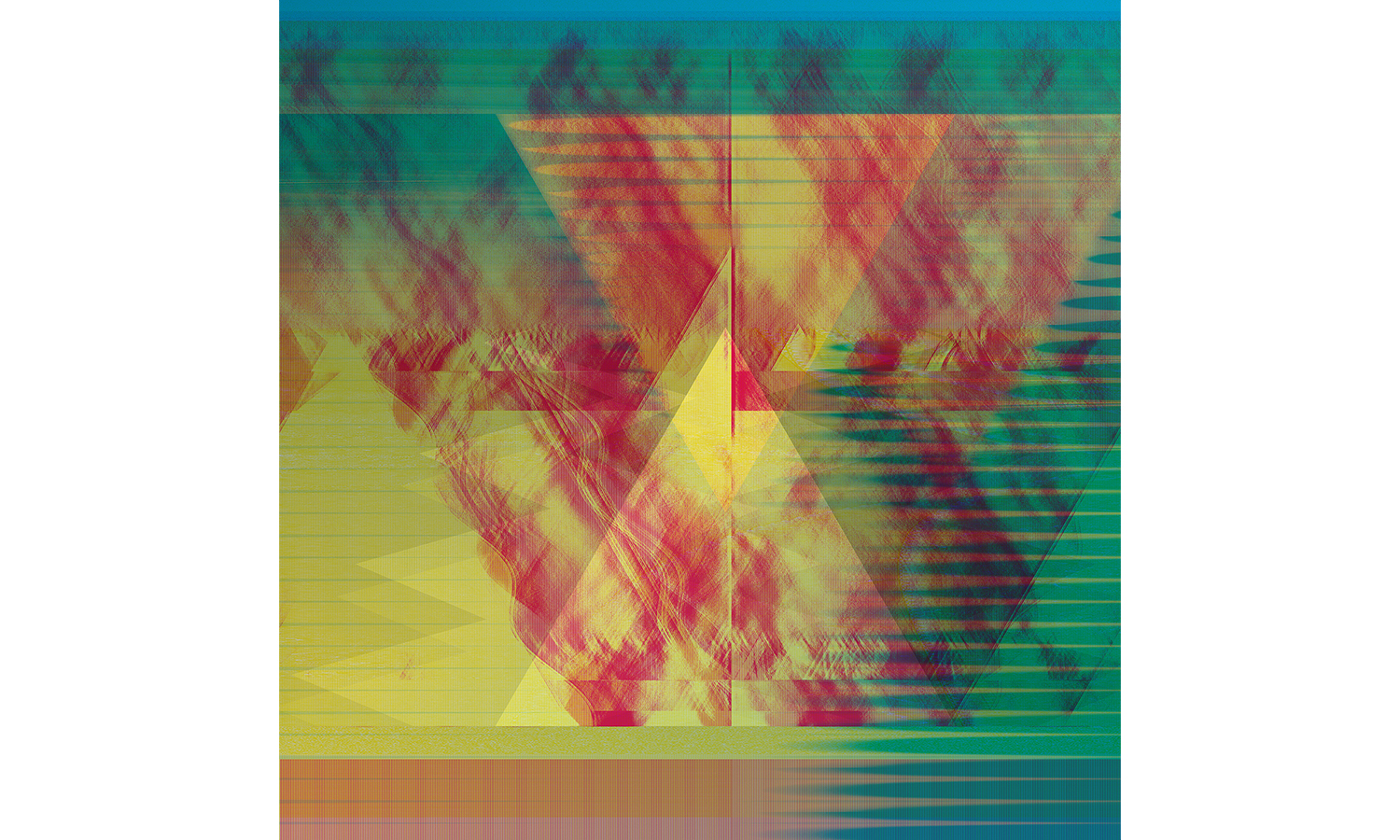

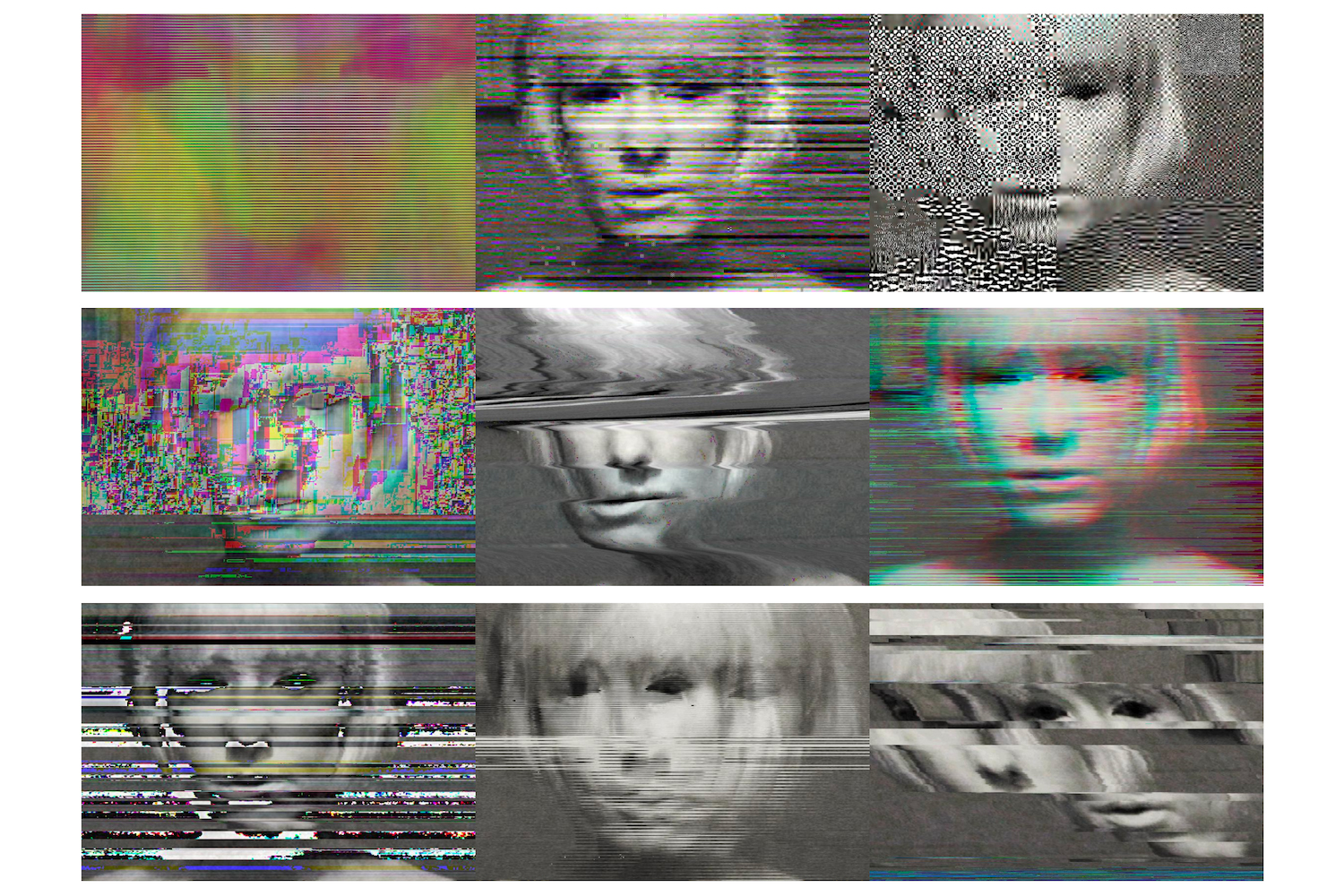

The intended use of the glitch is a political act, or rather a reaction to the conventional use of technology, which is flattening us. As Quaranta writes, “Yet, the more that medium becomes a mirror of power, the more noise becomes an interesting artistic strategy.” We can therefore think of glitching as a liberating act, in which the hacking of the medium opens the door to a more compelling and original work. Menkman looks for the unexpected and the uncanny, using the glitch not only to free a medium and its language, but also to broach what could not be expressed in other ways, as the curator claims. An example is provided by A Vernacular of File Formats, in which the artist makes the image deterioration process visible through the application of different types of flaw. The work is a story and an illustrated theory concerning the life cycle of an image and its reproducibility in the digital age. Starting from a black-and-white image in which the artist wears heavy make-up and combs her hair, glitching brings out the dramatic nature of the deterioration through the treatment of an image that fades over time, duplicated, more and more pixelated, until it almost disappears, only to then return with a strong chromatic component.

For Quaranta — channeling media theorist and art critic Boris Groys — Menkman’s introduction of a glitch between the image file (as an invisible string of digital data) and the actual digital image breaks the reproducibility cycle itself, liberating the image by being a mere copy and allowing it to have many unique lives.

For critical theorist and research artist Michael Betancourt, glitch art “develops the difference between being failure, representing failure (as the use of visual glitches in a dramatic, narrative work), and the semiosis of failure-as-aesthetic common to Glitch Art (its role as an artifact presented and used for aesthetic purposes).” Due to the ambivalent character of this type of art, where the image is left “as a coherent unit” but visualized in “an unanticipated visual form,” he argues that the public plays a fundamental role in mediating the meaning of the artwork. From this, we might surmise that glitch art finds itself not only in a style, in a procedural dimension, or in the interaction between man and machine, but also in the active involvement of an audience asked to critically interpret the artwork just as its familiarity with the digital system crumbles.

Given its elusive nature, the glitch remains an enigma. It can serve as raw material for artistic creation, as an artifact, a commodity, or process designed to refine our capacity for discernment. Italian artist Domenico Barra, aka Altered_Data, sees the glitch as a way to understand life and technology and develop critical thinking. In his work, digital manipulation intertwines with issues related to identity, memory, and language in order to promote social awareness. His solo exhibition “The Beautiful Minds” (2019), curated by Maria Pia De Chiara, took place at the Mapils Gallery in Naples in 2019. The exhibition focused on mental health, capturing the life of the artist’s twin autistic cousins and their family, aiming to offer the floor to those without a voice. Barra invites the public to approach autism with a new mindset, using the glitch as a transformative element while drawing a parallel between glitch art and the life of his cousins. In the same way that the glitch in art represents the ability of the machine to function beyond standards, offering a potential for creativity and creation, autism — the glitch in the life of Carlo and Antonio — becomes a new opportunity to establish a different kind of interaction, communication, and understanding.

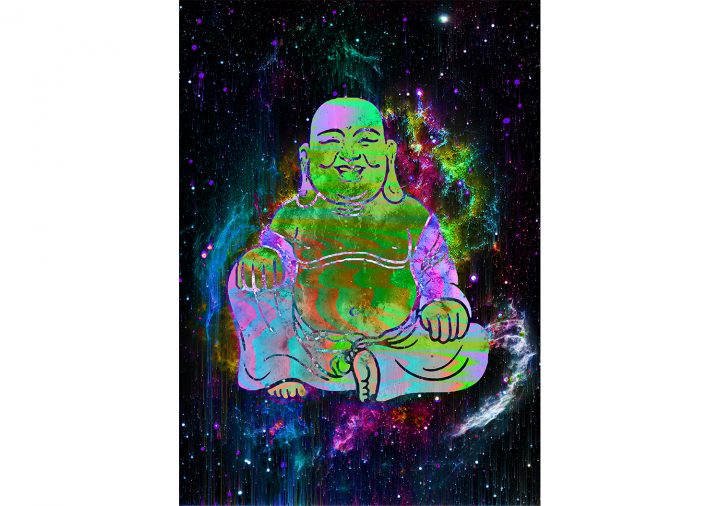

“The Beautiful Minds” are depicted through images linked to feelings, memories, events from everyday life, and objects that have marked the existence and forged the identity of these two men over time. At the moment, the exhibition can be viewed on the artist’s website, where we find a photo album accompanied by a model of a red Fiat 126 (Life is just a journey into memory’s valley, 2019), the car that took the family on vacation, that calls to mind a bygone era. One animation projected on a semi-transparent sheet (Electric Buddha, 2019) depicts a moment of joy for one of the twins, who enjoyed throwing cards in the air and watching their flight while planted like a Buddha. The installation Day by Day, Everyday (2019) suggests the life of the cousins in terms of medical treatments (represented by red and white pills), routine activities (a calendar), autism (a puzzle), and therapy (an inflatable pool). For Barra, the glitch becomes both metaphor and color, while new media art is the language and memory the glue.

The glitch ignites debates, encouraging the public to assert itself in the attribution of meaning. However, it can also perplex the uninitiated as an ineffable abstraction. If it hinges on our technical know-how, then it is only at the level of theory that we can find common ground. For it is only the concept itself — oscillating between failure and opportunity — that leads us to overcome the banality of appearances and face reality.