Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

Have you ever heard of Valeska Gert? If you have, chances are you know much less about her than her contemporaries. Born in 1892 in Berlin, Germany, Gert was a pioneering dancer, cabaret artist, and actress. Working across modern dance, theater, and film during the Weimar Republic, she created avant-garde pieces for stage and screen, many of which satirized and commented on contemporary social issues. Seeking to represent marginalized people who were exempt from bourgeois society, she portrayed prostitutes — one of her most well known and well documented pieces was titled Canaille (1919) — matchmakers, and outcasts, as well as abstract concepts such as boxing, traffic, and death. But despite her pioneering thematic concerns and multidisciplinary approach to creation, Gert has been largely excluded from the hallowed halls of art and dance history. Why?

According to Hungarian-born, Berlin-based choreographer Eszter Salamon, who has been creating work inspired by Gert’s life and oeuvre for the past five years, there are two main reasons. Firstly, as a solo artist, Gert didn’t invent a style or school like Mary Wigman or Rudolph Laban, both of whom hold greater prominence in dance history. Then, more hauntingly, is the fact that Gert was Jewish. “Her invisibilization was orchestrated before, during, and after the Second World War,” says Salamon: while the Nazi’s were in power, she wasn’t allowed to perform, spent many years in exile in London, New York, and Zurich, and her work was included in both the Nazi’s degenerate art exhibition (1937) and the anti-Semitic “Eternal Jew” exhibition in Munich (1937–38).

Gert struggled to show her work in Germany even after the Nazi party was dissolved. “She had all kinds of administrative problems making her situation impossible. Theater gave up on her,” says Salamon. “She talks about it in her autobiographical book, saying that when she came back to Germany she had big interviews for one week, but that after that people tried to silence her because she was talking about concentration camps and because she wasn’t anti-Stalinist enough.” As a result, Gert had to continue to make things underground, creating her own establishments such as Hexenküche (Witch’s Kitchen) cabaret in Berlin, which opened in 1948.

Even today, Salamon says she has struggled to get theater bookings for her work on Valeska Gert in Germany. “I had a pretty serious shock when I realized that the work I made around her for theaters has only been presented in two cities in Germany. It’s not only about sounding like an angry artist, because it’s beyond that. What does it mean? What is problematic there? What is the current, very real, difficulty with addressing certain questions?”

Due to this historic erasure, many people today do not know Gert’s name and how many artistic developments should be attributed to her. For example, “while silence is viewed as being invented by John Cage in 1949” — the composer’s landmark composition 4’33 (1952) instructs performers not to play their instruments for the duration of the piece — “I say that Gert conceived the equivalent in dance, immobility, in her piece Pause (1920) thirty years before,” says Salamon, referring to the piece Gert would perform in between newsreels at the cinema. The way Gert worked across mediums and performed in nontraditional settings was also ahead of its time. “Today we use institutionalized language and terms like ‘expanded choreography.’ But she was doing this in the 1920s.”

When asked how she came to start creating work about Gert, Salamon admits that “it wasn’t love at first sight.” It wasn’t until she did deeper research that she realized that she had a strong connection to Gert’s practice, particularly her use of the voice. “Since the beginning of my practice I have used voice in my work, first as an extension of movement and bodily expression, and later as a way of creating a discourse to challenge the mute body that dance has constructed for several centuries,” she says. “Discovering that Gert started using the voice in 1920, at the very beginning of modern dance, blew my mind.”

This point of comparison inspired Salamon’s first ever work on Gert, Monument 3: Love Letters to Valeska Gert, a sound installation of two voices presented “in a dark room, in relation to the Beggar Bar she established in New York during her exile,” as part of the 2016 group exhibition “Art-Music-Dance. Staging the Derra der Moroda Dance Archive” at the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg. Since then, Salamon has created several more works exploring Gert’s life and legacy: Monument 03: The Valeska Gert Museum, an embodied museum consisting of performative acts that has been shown in museums and gallery spaces across Europe; and Monument 05: The Valeska Gert Monument1, which explores similar themes in a theatrical context.

While Salamon takes inspiration from thorough research into Gert’s life, she stresses that her pieces are not reenactments. Instead, she describes her methodology as “hallucinating” history. “There are so few elements left of Gert’s work, so this idea of hallucinating means that I recognize my position of not knowing and constructing with fragments,” she says. Salamon often uses these small snippets of information — such as the titles of Gert’s works, photographs of performances, or anecdotes from her primary source, Valeska Gert’s third autobiographical book, Ich bin ein Hexe — as choreographic departure points, using her imagination to fill in historical gaps. At other times, she creates what she calls speculations by combining unrelated fragments to inspire performative actions.

This approach is evident in the choreographer’s upcoming project, Reappearance, which will bring together two anecdotes from Gert’s autobiographical writings to inspire a triptych of films. Having already explored Gert’s work through live performances on stages and in galleries, revisiting this subject matter with film presents an opportunity to create different encounters and meanings — to see what different contexts are capable of, and how they can activate audiences. The choice of working with film also relates to Gert’s extensive involvement with the medium throughout her life, from performing in between cinema reels in Berlin to appearing in films by the likes of Pabst, Renoir, Fellini, and Fassbinder. “Gert liked to work with the camera; she wrote that it can be a tunnel to the future.”

The first anecdote in Reappearance is inspired by stories of Gert’s practice of dancing naked for a pianist (and lover) who would give her compositions in exchange for her performances. “Gert never danced naked on stage. She had a solo called Orgasm (1922) and presented herself as a prostitute in Cannaille (1919), but she worked on these ideas in a certain way without using nudity,” explains Salamon. “I found it very interesting that she had this parallel, private practice.” The second anecdote is from Gert’s time spent in exile in London in the 1930s. “She talks of how she wanted to make a film, and how she recited her ideas to someone who would type them up for her,” says Salamon. After three weeks, however, Gert realized her typist was a drug addict, and hadn’t recorded any of her ideas clearly.

Salamon describes her practice as composition rather than discovery. “By putting things into a relationship they weren’t previously, new meanings or even knowledge can be constructed. It’s a complete break from historical objectivity and offers the potential to develop a relationship to history that isn’t based on those terms and traditions.” The choreographer is a firm believer that artists should be part of history making. “There is no one model or obligation for how we should address history: it can be critical, poetic, through writing, questioning, deeply researching or taking inspiration,” says Salamon. “We should not separate ourselves from the action of relating to history, because then we are also separating ourselves from a certain kind of responsibility. What knowledge and artistic practice can circulate and gain relevance?”

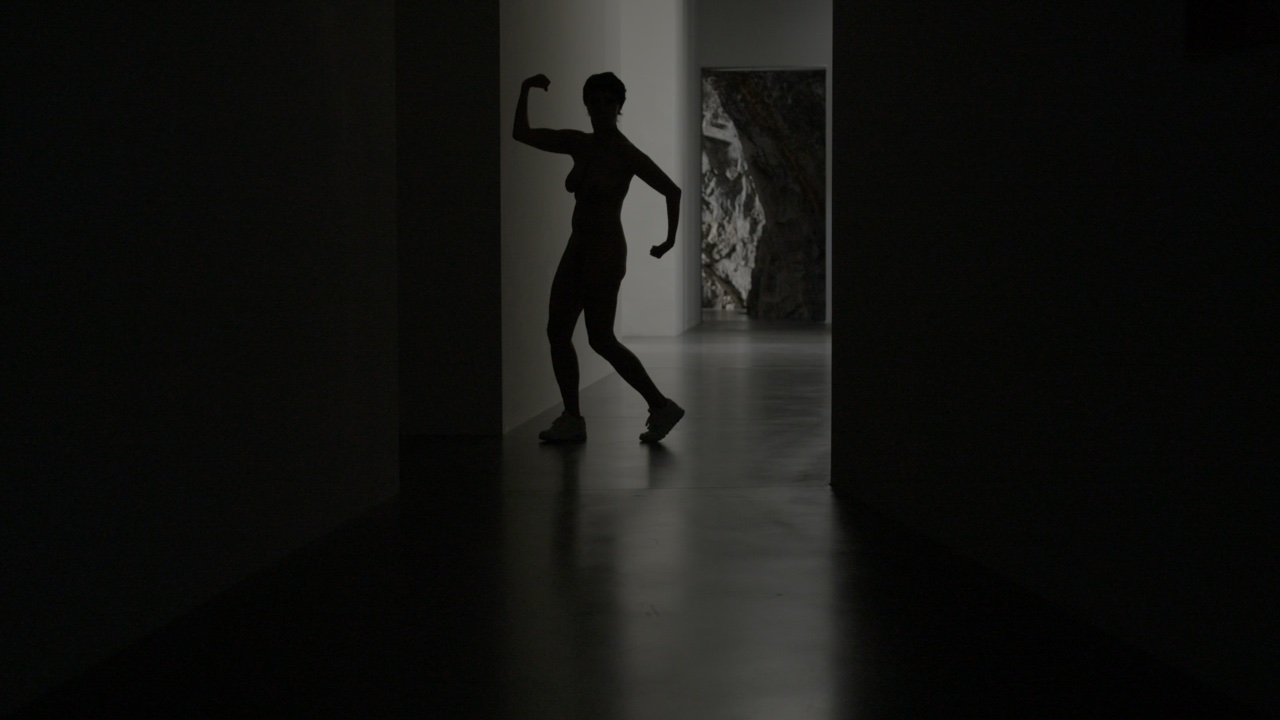

The lack of recognition for Gert makes it all the more poignant that Salamon has made it her mission to present her Valeska Gert Monument and Valeska Gert Museum in collaboration with prominent institutions all over Europe, such as Centre Pompidou in Paris and Akademie der Künste in Berlin. Most recently, for Reappearance, Salamon has collaborated with Muzeum Susch, a new contemporary art institution in Susch, Switzerland, founded in 2019 by Polish entrepreneur Grażyna Kulczyk and focusing on presenting the work of omitted, overlooked, and misread female artists. She filmed the first installment of the series in their gallery spaces.

Filming at Susch “was a product of circumstance,” says Salamon, explaining that while she knew she had a residency planned at the venue, she hadn’t decided which project she would work on until a few months before she arrived. But despite being a serendipitous setting, Susch ended up imbuing Salamon’s film with new layers of meaning. The museum’s proximity to Zurich, for example, relates to the fact that Gert lived in the Swiss city for several years after returning from her exile in the US, establishing a cabaret bar, Café Valeska, there in 1947. Another surprising layer of meaning was created when Salamon discovered she would be shooting the film with an exhibition of work by Belgian Pop artist Evelyne Axell — Muzeum Susch describes her work as “populated by an all-female universe, transcending the established iconography of Pop art at the time and reclaiming the discourse of women’s sexuality” — as a backdrop. “It created a kind of triangulation between Axell, Gert, and myself, which I didn’t premeditate,” she says.

With the first film currently in its final stages — yet without a current premiere date — Salamon already plans to shoot the next installment of the series in HAU1 in Berlin, “in an empty theater… so it’s relevant for different reasons,” says the choreographer, alluding to the disastrous effects of the global pandemic on live performance. “There is a great potential for questioning theater spaces at the moment: What can be done in a theater today? And what can theaters as public spaces — as well as theater as an artistic practice — become tomorrow? What do they want to care for, and what kind of emancipatory processes do they want to support, host, and share?” The third installment will take place in a cinema in either Budapest or Paris, where she and Gert have both lived and performed.

While some artists are reluctant to work with established institutions due to their sometimes problematic histories and infrastructures, for Salamon it’s important to challenge from within the system. “Because of this whole history around Valeska Gert, and the failure of institutions, I don’t want to attack them frontally, but to collaborate with them to address questions and to create a dialogue,” she says. “These institutions, along with many other people, including journalists, theoreticians, programmers, theater directors, and so on, all determine what becomes history. Maybe they don’t want to take responsibility for it, but they have too much power, which is a real problem,” Salamon adds. “There needs to be a collective effort to activate dialogues and face reality in order to help us to see other exclusions.”