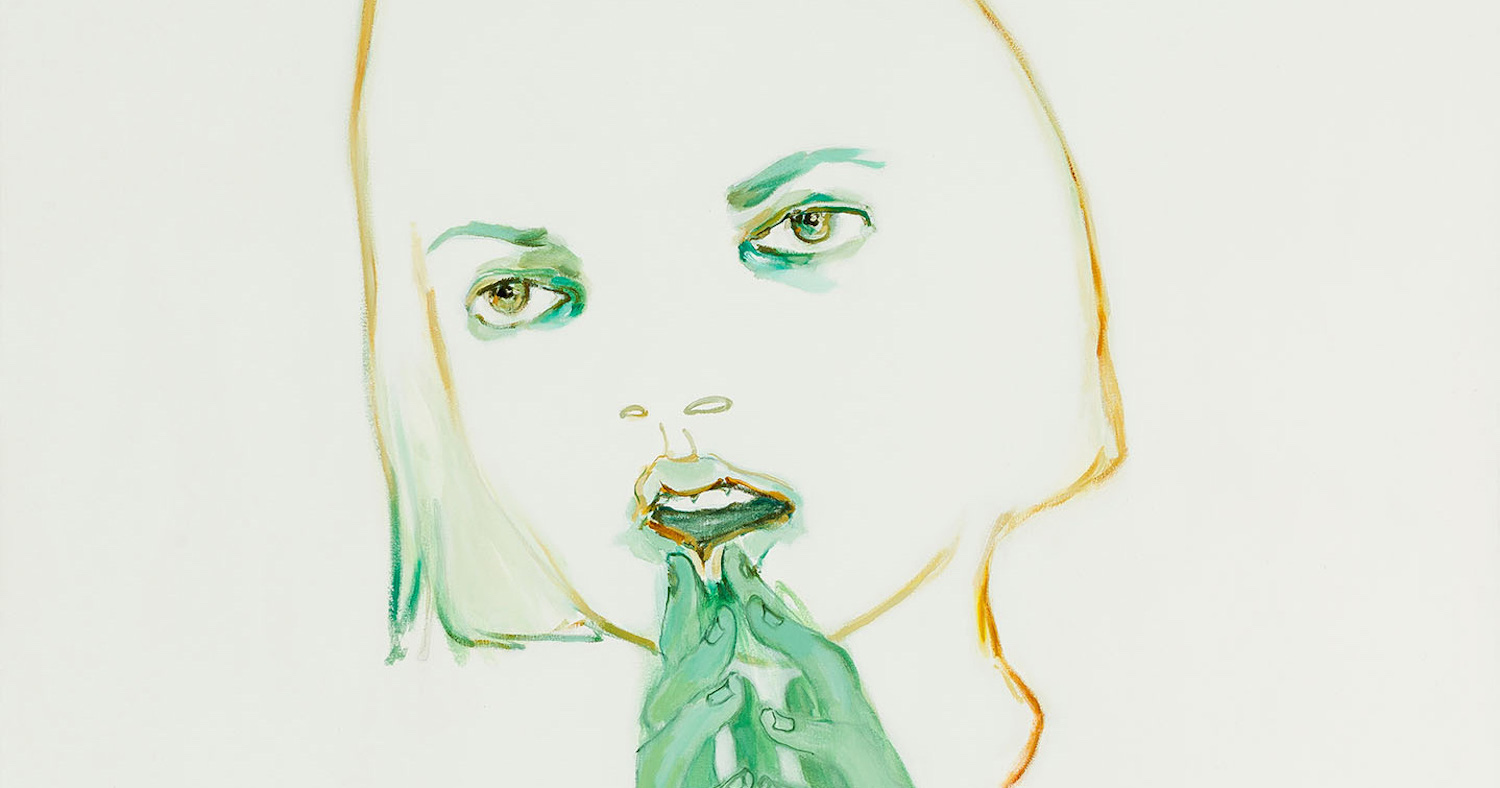

The imaginative power of PriscaVera’s campaigns is one of the driving forces of her brand.

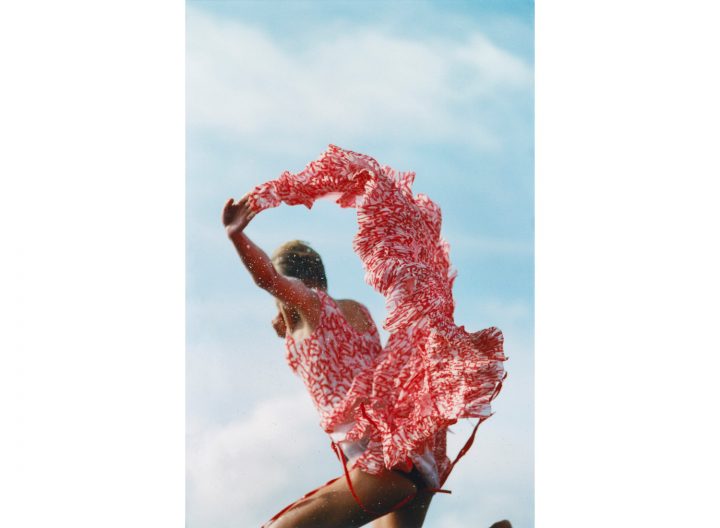

The women wearing PriscaVera’s clothing express a natural drive that each of us would like to embody. They appear daring for the pleasure of it, living in constant adrenaline to access a new level of freedom.

Shot through the lens of Francesco Nazardo, PriscaVera is energy in disequilibrium, and an infinite possibility of action. Everything becomes possible and elusive at the same time.

The imagery of PriscaVera shows an experimentation that either erupts in freedom or falls asleep peacefully on a romantic sunset. The emanation of color juxtaposes with shapes and patterns enchanting the eyes of the viewer. It’s dada, it’s punk, it’s classic, it’s post, it’s modern. Only two letters matter – PV – essential for the true contemporary warriors of PriscaVera.

Gea Politi: Describe a typical day for Prisca Vera Franchetti.

Prisca Vera Franchetti: At these early stages of building my own business, by the time I wake up I am immediately in a working flow. There is just so much to do. I try to balance creative and business decisions and respond to the urgency of whatever needs to be done. I spend most of my day at my studio, researching and sourcing fabrics and trims. I’m also at the factories a lot; being in close contact with the development and production process is very important to me. I am a bit of an extremist, an all-or-nothing kind of person, so more often than not I can’t help myself from working every day, even on weekends. When I get a break from work, I usually travel and shut off completely.

GP: Would you say your work addresses any issue in particular?

PVF: I work with independent small textile and garment makers in New York, Los Angeles, Portugal, and Italy. I care very much about the themes that most people do not really see when it comes to making clothes, from research, sourcing, and design, to all the intricate steps involved in developing fabrics, patterns, tailoring, and embellishments. I believe in paying employees a fair wage and working with factories that value the time, skill, and talent of their craftspeople. I hope that my designs reflect the respect for quality and all the labor that goes into making and showing them. If a garment is too cheap, someone somewhere is paying for it. I want to bring awareness to this through my work.

GP: You seem interested in the mixing of different cultures, with the intent of modernizing them.

PVF: I am. We live in a very accessible world — we can easily research and learn about other cultures and customs or have an in on something that used to be hard to explore. There is so much visual stimulation and easy access that the reaction to the overflow of material is and should be to protect heritage. I do believe that within the respect for other cultures it is important to not stop finding inspiration outside of what we feel easily connected to. We should all talk about and represent what we know, but I also feel that it is important to not lose a sense of curiosity.

I am constantly learning new things, especially in regards to technique. Conceptually, I find inspiration mostly by looking inward and exploring what feels familiar. A lot of this has come from memories of my childhood growing up in Italy, and sometimes outside influences overlap. For example, a few seasons ago I designed a collection that was inspired by Tekken 3, the Japanese fighting arcade game. I was inspired by the videogame because of my obsession with it as a kid — the body language and power of the characters really resonated with me and I remember having a very personal connection with them. There is evident Japanese influence within every aspect of the game, but by the time I produce a piece of clothing it gets broken down into so many layers.

GP: What is contemporary to you?

PVF: Disorder and absurdity feel contemporary. When I think of the definition of contemporary what comes to mind is not the present but more so a reaction to the present that will be projected into the near future. I aim to react and forecast the ideas of today into the clothing I make.

GP: Has it ever happened that a disastrous event turned out to be an excellent result/outcome? How often do these types of “accidents” happen?

PVF: I cant pinpoint a specific event, but more often than not when something tragic happens it becomes a helpful learning experience. Even if not, that is OK because some things you just cannot control. Fashion operates very quickly, and we are a small team, so you have to figure out how to roll with the punches and learn how to let go. This has been an important lesson for me in my work and my personal life. Dealing with something disastrous leads often to a realization, a better outcome, or simply just a little step closer to thicker skin.

GP: You are not only a clothing designer; you are an image creator. Your campaigns are never excessive, but they communicate a sense of realness and comfort. People who wear your clothes seem to be wearing a second skin.

PVF: I value wearability as much as a surface to project oneself onto. In my campaigns I am not trying to dictate an image, but to provide a possible feeling of how the collection can be understood. I want to leave space for my clients to contextualize the clothing in their own sphere.

GP: Your last campaign seems to follow a precise aesthetic. Will you tell us more about it?

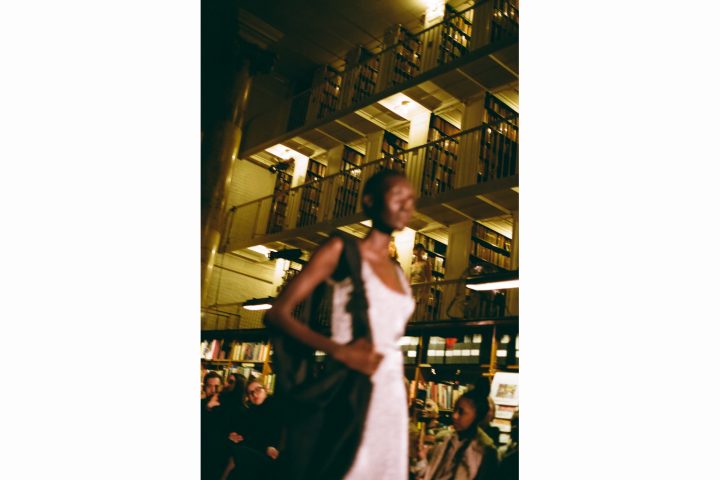

PVF: The experience of shooting the SS21 look book & campaign is actually very relevant to your question above. It was literally one disaster after another that turned into an excellent result! Some location permits were revoked, flights were delayed, we had to shoot safely during a pandemic without compromising our vision, etc. A lot of things that were planned and fell through required immediate workarounds, and, luckily, I have a talented collaborative team that was smart and quick thinking. When disasters happen, it is crucial to trust in the skill, experience, and vision of the people you are working with.

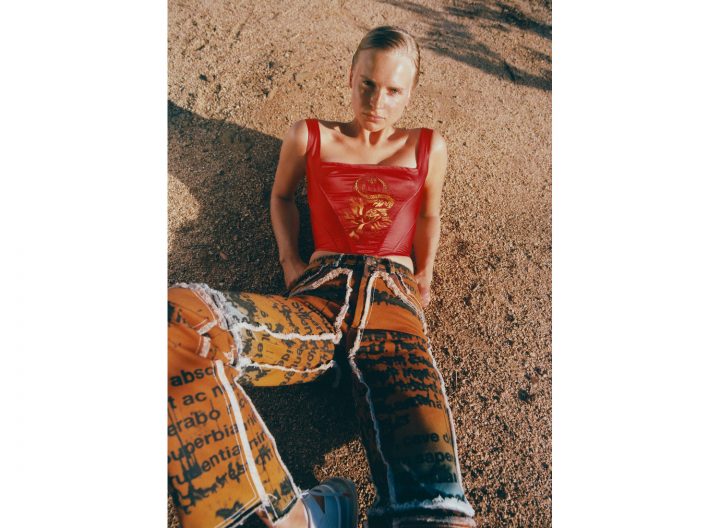

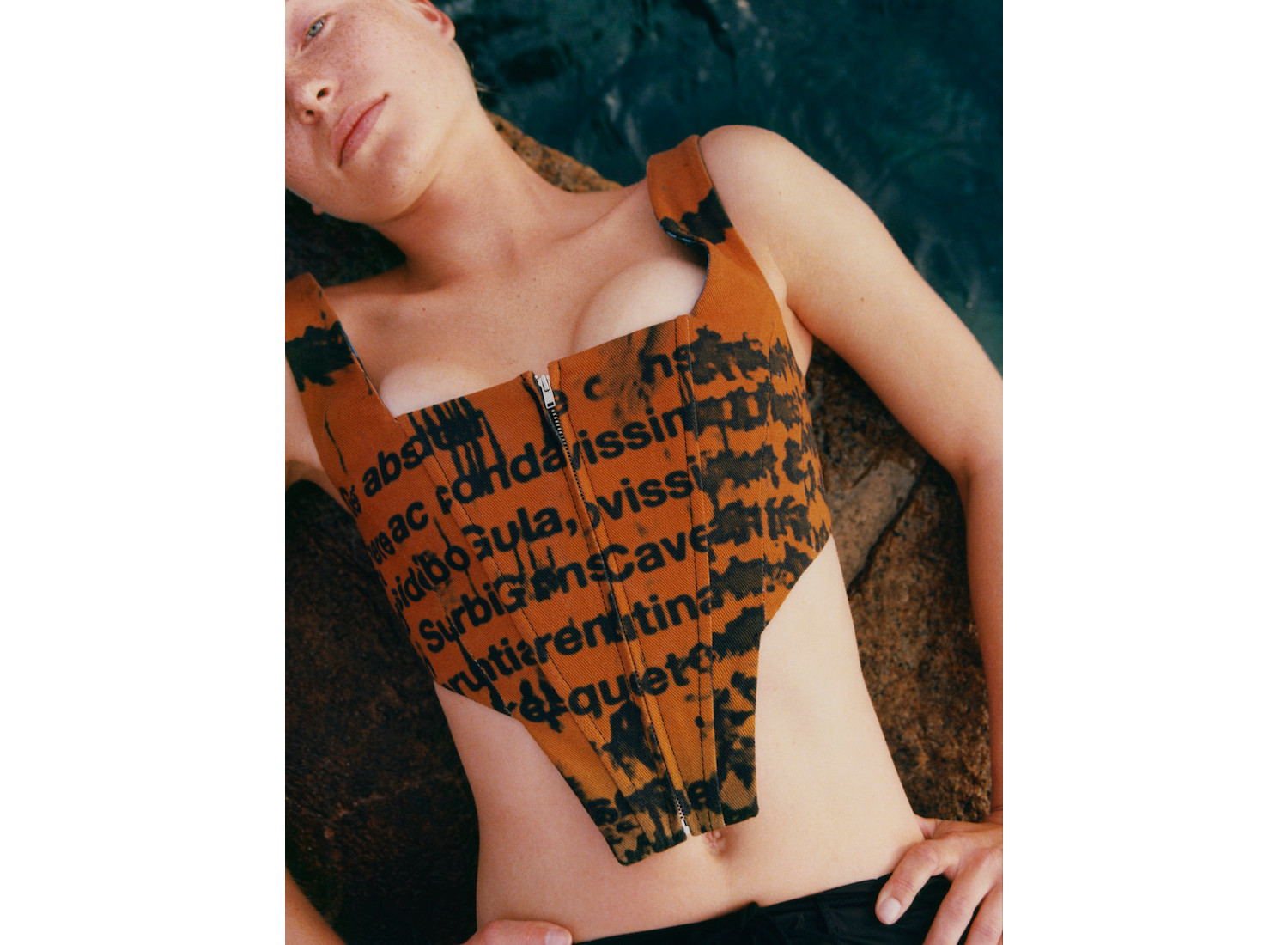

I decided to shoot SS21 in Rome, my hometown. The collection was an exploration of blurring the line between vacation and work in an unprecedented time when neither felt natural. As the world becomes our office, what constitutes work and play begins to collapse and become one and the same. I was affected by what was happening outside, and the shift in my creative process determined the outcome of the clothes. The inspiration behind the collection was what was actually happening in the shoot, so it felt like a very authentic experience that kept me inspired.

GP: Would you define your brand as “a logo”?

PVF: I wouldn’t say so. It is so much more than that. I think the reason someone buys a piece of clothing is the story behind it — the designer’s world and the fantasy that you buy together with it, most importantly a set of ideas that the customer shares with the designer. The customer has to feel like they belong and relate to the world they are buying into, and that takes time, effort, and vision to create.

I am very fascinated with the idea of logomania, probably because I grew up with it in the ’90s and have watched it evolve. I have explored the reinterpretation of “the logo” in my collaboration with Daniel Sansavini, who has been the brand’s graphic designer since its inception. We like to play around with this idea that each collection has its own logo, which then becomes a T-shirt graphic, a fabric manipulation, and embroidery — or even just a sticker. The creation of “this season’s logo” forces me to think about what the collection is about in one image, or one font, and that almost always opens other doors: other ideas, other prints.

GP: Is your work strictly collaborative? Or are you realizing the first part of the work alone? Where does your work start? Does it start from the collaboration or from other types of forms? What is the process?

PVF: I used to start off alone. The early stages of designing a collection was a very personal process for me. Once the direction was defined, I would involve people step by step. Recently that has definitely changed, and I have started to rely on the open conversations I have with the people I work with. I am frequently bouncing ideas and asking for opinions, from the initial concept all the way through to its communication and medium.

I share a very specific vision with my friend Francesco Nazardo, who I frequently collaborate with. He has been shooting all of our campaign images since the very beginning. We draw up ideas for the shoots together. I also work closely with Delphine Danhier, who has become an essential input creatively over the past years. The making and showing of the clothes is a connected, collaborative process.

GP: How important is inclusivity and community in your work, and how much does your community affect your creative process?

PVF: Community is extremely important to me, whether it’s the people working on the collections or those who actually wear the garments — my audience, so to say. Having a business that creates concepts means sharing ideas and coming up with new ones with people I deeply respect from all different walks of life. I’ve been lucky enough to form genuine relationships with the people I’ve met and collaborated with through my work, which is absolutely priceless.

GP: Can you share your idea of “femininity”?

PVF: Femininity to me is the understanding of oneself, the acceptance of one’s delicate human nature within the roughness of our surroundings. Being feminine means being in charge of one’s sentiments and showing them — wearingthem proudly, being playful freely. It is unapologetically being who we are and being comfortable with that. I don’t believe femininity has anything to do with roles, gender, or sexual orientation. There is no femininity if there is no freedom.

GP: What is authenticity to you? Do you think it still exists?

PVF: I think authenticity exists. If it were dead, there would be no point in doing what I do. To be authentic also means to have courage. Today, you need to be able to have an open dialogue about your point of view and your beliefs — to exist in this mindset and stand behind it. It’s about your story, and the story needs to be coming from a real place, feeling, or opinion. Otherwise it isn’t interesting. Looking for connections is what we desire as human beings — and ultimately what sells.