What do the Norse (and cinematic) deity Loki, Bugs Bunny, and the Joker (Batman’s eternal antagonist) have in common? They’re all tricksters, endowed with extraordinary shrewdness and ambiguous morality, in keeping with that timeless mythological, folkloric, and literary category. They take advantage of others, whether in comical or sinister ways, to achieve their own ends or even realign the very axis of reality to suit their tastes.

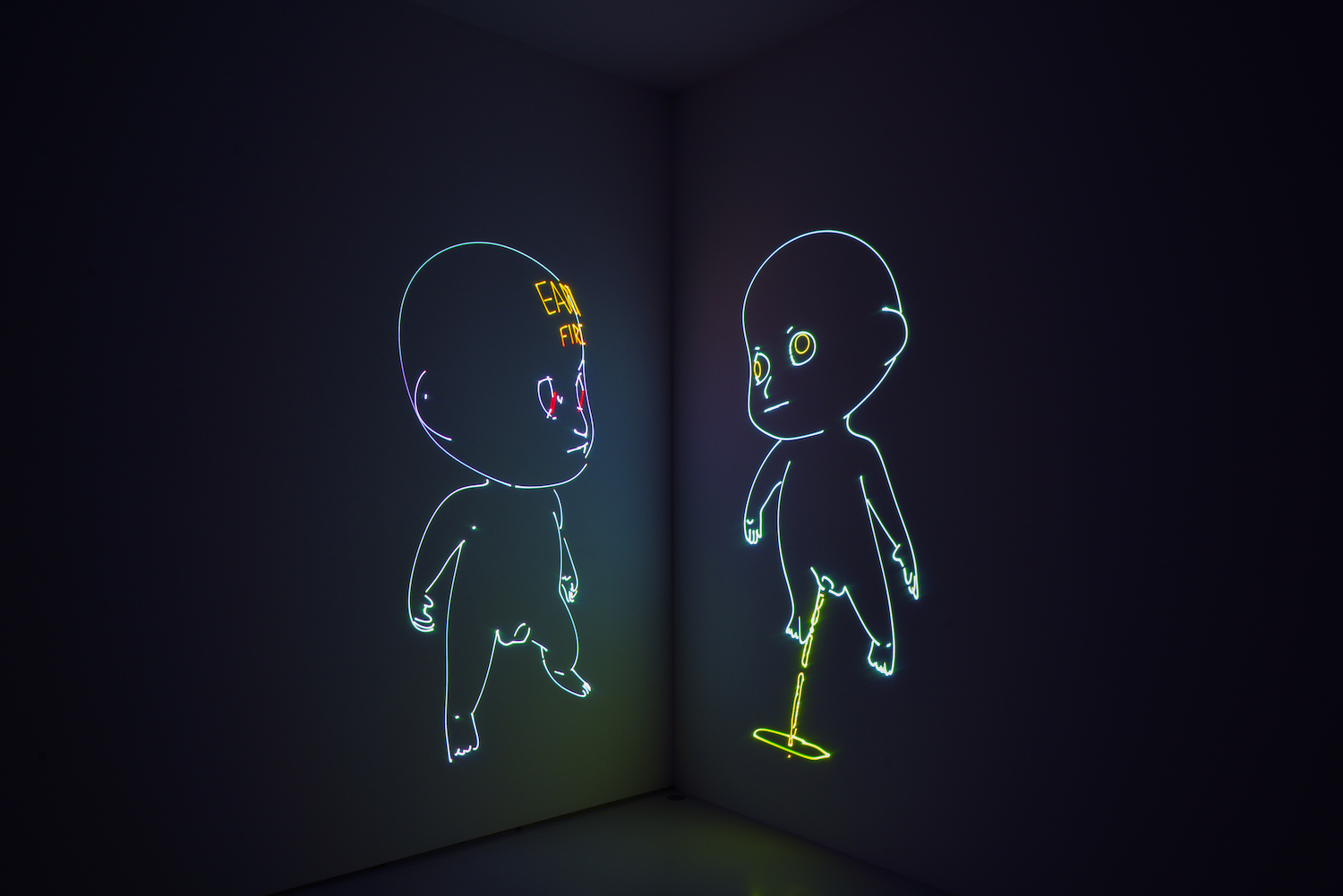

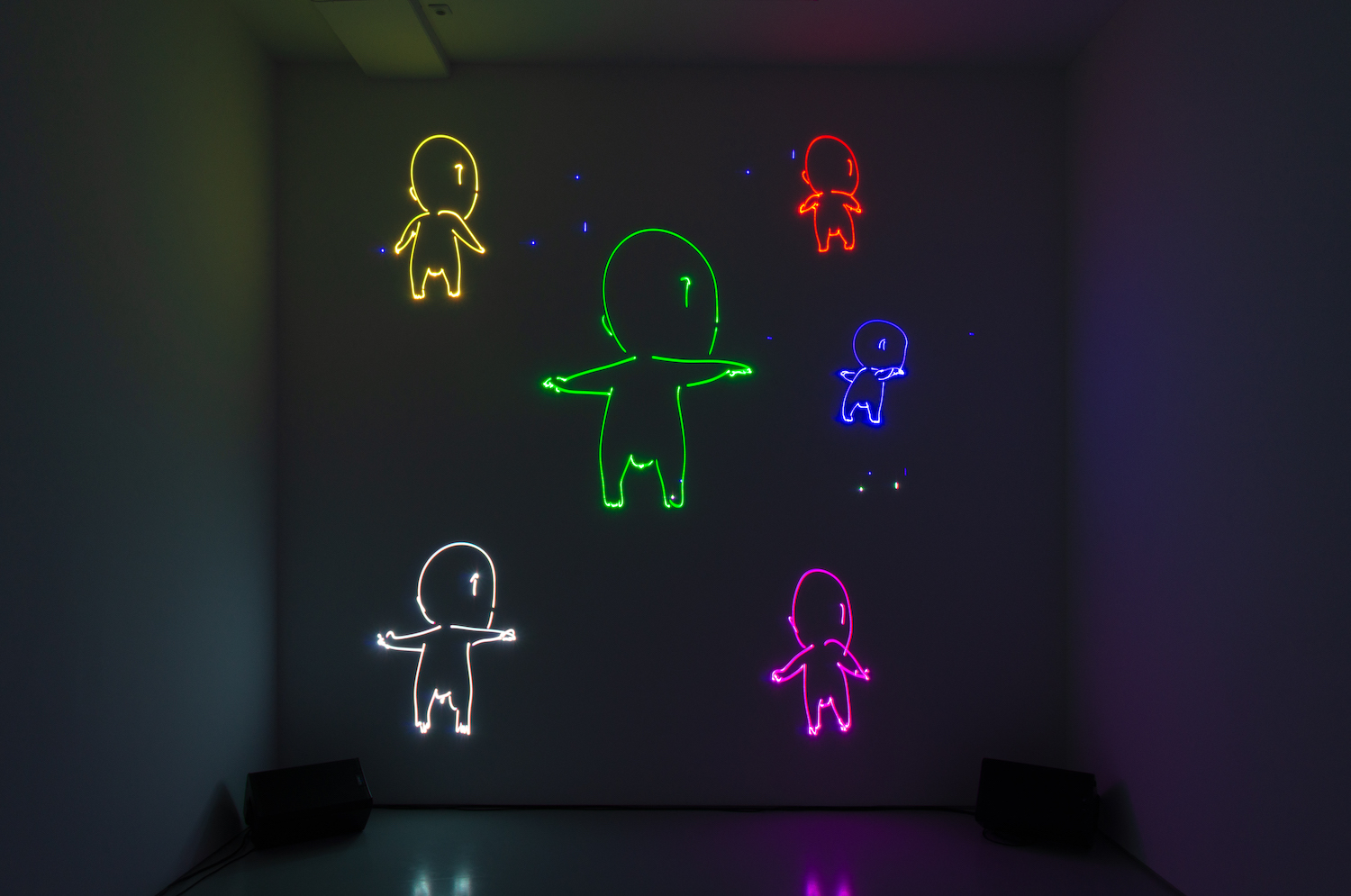

The fox Reynard has tricked countless “victims” in popular Northern European tales since the late Middle Ages. He has also been a main protagonist, in a mercurial and trenchant version, of the artworks that have brought young British artist Matt Copson (b. 1992, Oxford, UK) increasing popularity over the last half decade. A tireless and sagacious companion since Copson’s degree show at the Slade School of Fine Art in 2014, the totemic animal is, for this exhibition at High Art, replaced by a group of children animated by polychrome laser beams projected all around the Parisian gallery’s magnificent neoclassical rooms.

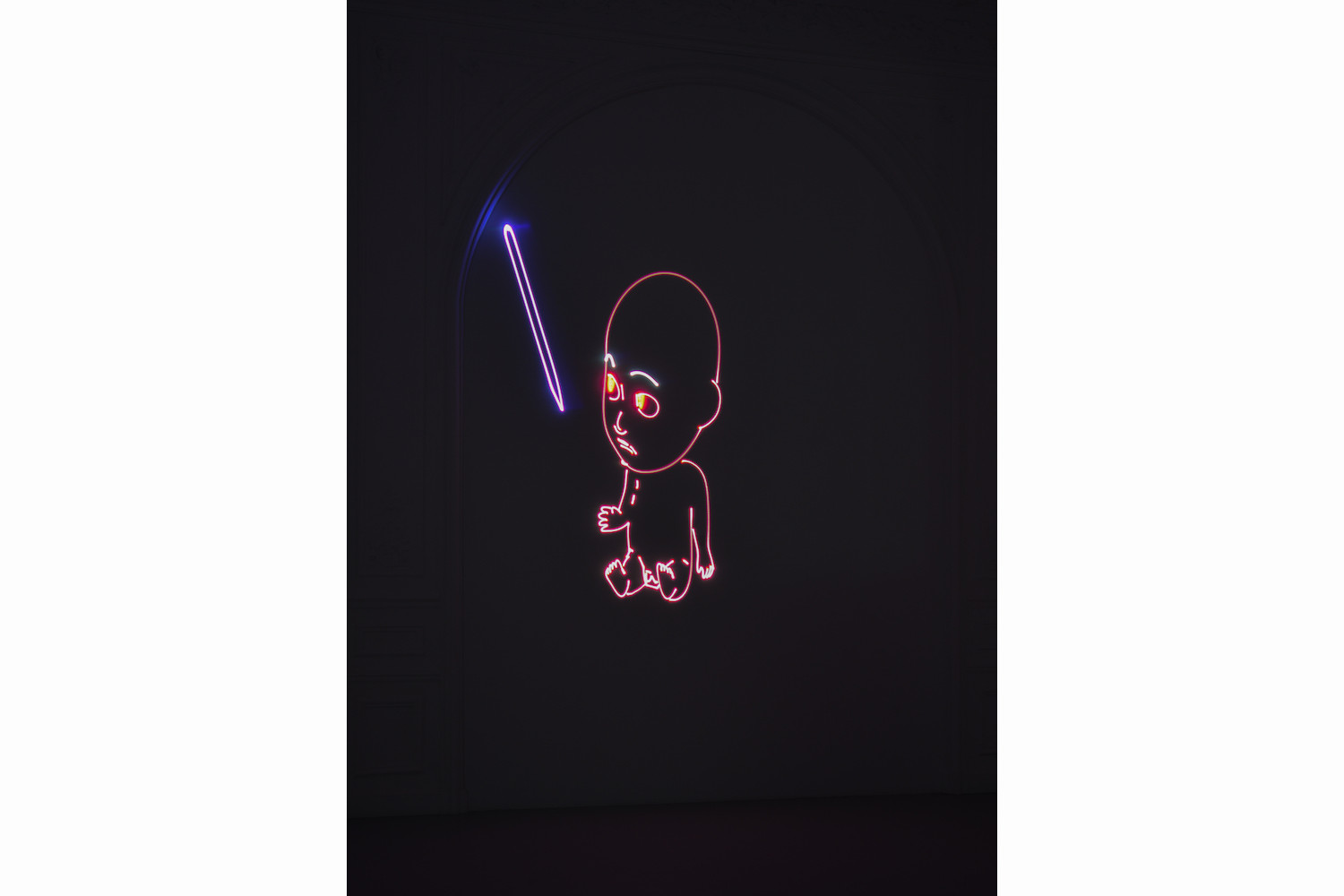

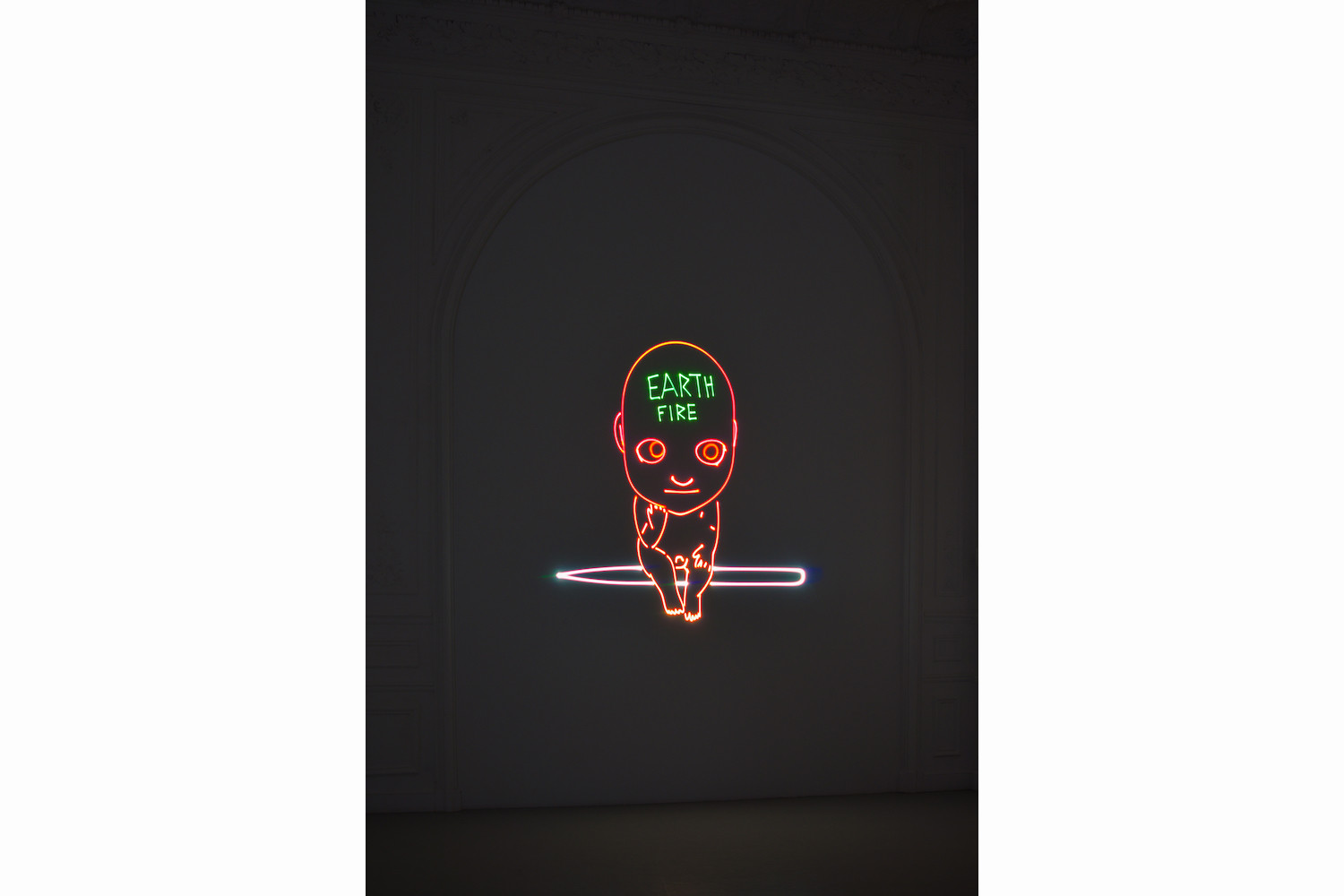

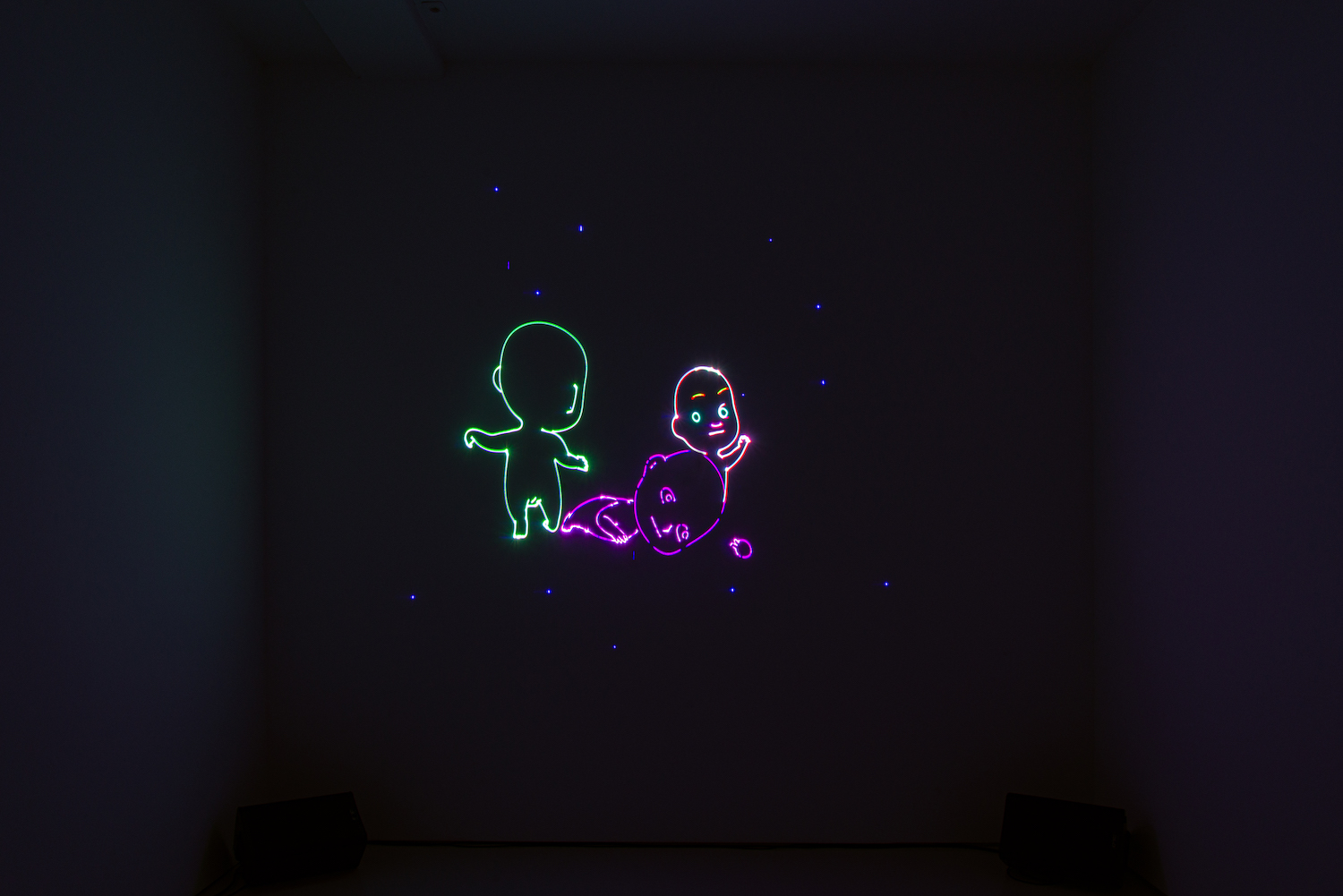

Always fascinated by the humanization of animals for allegorical purposes, here Copson tackles themes of pathetic ambition, existential fury, narcissism, and failure using infants who, tellingly, never grow up. Perhaps in homage to the fact that the gallery is located in the same building where Georges Bizet composed Carmen (1875), “Coming of Age” is a three-act opera in which we witness the creation of a child by the hand of a malevolent superior being who trains him in the use of words, images, and pessimism: “My integrity / was compromised at birth / My sincerity / set fire to the earth / Oh Mother, / this freedom is a joke! / I wonder what’s living with no hope?” sings the boy soprano to music composed by Caroline Polachek.

The child will draw a mirror clone of himself, by whom he will be erased, but who will give life — extracting their bodies from his chest in mythical allusion — to other versions of himself. A potentially infinite, playfully macabre cycle of births and deaths is implied. “I know everything / to teach / So trust me when I say / The doorknob’s always out of reach / The earth is choked by fire / The End.” The preceding is one of the verses that most delightfully summarizes the Promethean puerilism of the minute creatures. Copson, on more than one occasion, has confessed to being a fan of the animatronics one encounters at theme parks such as Disneyland. The characters are perpetually forced into the same sets of movements — fixed, however sudden or apparently slippery they might appear, and motivated by a choreography characterized by very limited room to maneuver. The exhibition gives free rein to this curiosity regarding limited free will, recursive narration, and the suspect presence of a demiurge — shared by the luminescent figures on the walls and by the spectator, who is guided by hints of sound and lights from one hall of the gallery to another — in a hilarious and at times touching way.