“Listening In” is a column dedicated to sound, music, and listening practices in contemporary art and its spaces. This section focuses on how listening practices are being investigated and reconfigured by artists working across disciplines in the twenty-first century.

Kyle Devine: Can you describe the works that make up your “Testimonium” series, which is being shown at Fridman Gallery in New York from February 27 to March 27? I understand that these works take on three different forms and will fill the two floors of the gallery.

Jacob Kirkegaard: The “Testimonium” series explores waste in different formats. It is made up of three sound and visual works that I created from recordings and photos I made at one of the world’s largest landfills, the Dandora dumpsite in Nairobi, Kenya, and at very modern recycling and wastewater facilities in Denmark and Latvia.

Testimonium I is a sound and video installation that combines acoustics and images from the sites I visited, which will be shown on the main floor of the gallery. It was important here for me not to make any distinction between Africa and Europe, but to show that waste is global. Testimonium II will be played in a darkened listening room on a separate floor. It is an eight-channel sound piece, rich and detailed, which unfolds to create an immersive situation. It is an intimate portrait of waste from the inside. Testimonium III offers a large photograph from the Dandora dumpsite, where areas of the waste tend to burst into flames. It presents a visual account of what is creating the sounds heard in the other pieces.

KD: Some of the themes I hear in “Testimonium” include relationships between surfaces and depths, interiors and exteriors, the functions of documentary versus the forms of abstraction — and generally the idea that waste is practically everywhere but ideally elsewhere.

JK: I do try to go beyond the surfaces of things. I wanted to access waste by listening to its inner life. By using sensors I can enter the interior of a tin can, a pile of garbage, or a stinking pool of wastewater. I explore the depths beneath these surfaces, hearing their sounds, making waste less alienated and less alienating.

KD: I have dealt with some similar themes but in a different media format: writing. Across two books, Decomposed: The Political Ecology of Music and Audible Infrastructures: Music, Sound, Media, I have been asking what musical commodities are made of, how they move through the world, and what happens to them when they are disposed of. It turns out that our aesthetic and affective investments in music and sound have a variety of hidden but troubling human and environmental consequences. For some people, this has been surprising — and hard to swallow. Yet I find that we live in a moment when a certain kind of how-it’s-made-ism also exerts a strong force on the imagination. There is a near obsession with object biographies as well as supply chains and waste streams. So I wonder if there might be some challenging conflations between the kinds of critical work that we’re both invested in, on the one hand, and the field of attraction that seems to define contemporary consumer capitalism, on the other. In fact, pulling back the curtain seems to be a very effective way of selling products and services these days. I’m thinking of certain types of coffee or clothing, certain types of restaurant, certain types of butcher or brewer, and so on. Part of the consumer experience is knowing where a product comes from, who makes it, and how its various forms of pollution and waste are handled. If these kinds of unmasking can also serve consumer capitalism, I wonder whether you think sound art or music writing might offer something more than demystification or awareness-raising. We’ve found ourselves in a moment when general awareness of our planetary crisis has never been higher, yet awareness alone does not seem to be generating the strength or speed of response that is required.

JK: I think that sound — and the act of listening — can bolster our deeper senses. In order to really listen, you need to be quiet. And when you’re quiet, you are receiving information instead of being preoccupied with fast decisions and readymade conclusions.

“Testimonium” is about waste. How do we understand it? Perhaps we try to Google it. But I wanted to listen to it — to hear the way of the waste. Where does it go? If it had a voice, what would it say? Waste doesn’t speak a language but neither does it speak in tongues. So I decided to follow the waste with my microphones.

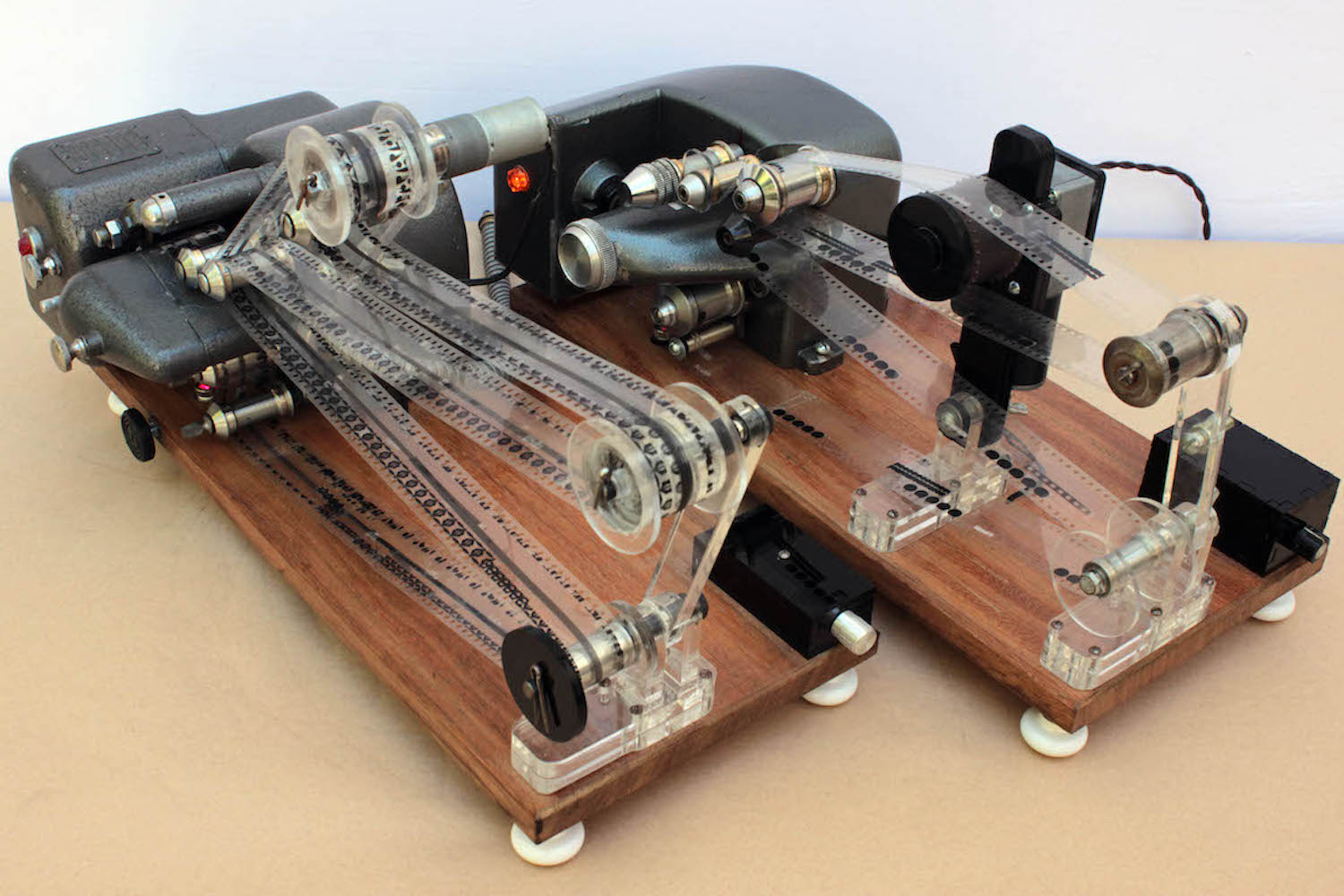

But how do we listen? I thought, “Waste is something you want to get rid of. Otherwise it isn’t waste.” So I found it necessary to get as close as possible. I stuck vibration sensors inside endless piles of organic waste at a large dumping site in Kenya, and on massive incinerators at an advanced waste management facility in Denmark. I dipped hydrophones into wastewater and contaminated rivers. I pointed acoustic microphones at metal, glass, and plastic as these materials were sorted by hand or machine. These kinds of recordings allow the listener to go beyond the miasma of discarded matter, into its physical core and industrialized journey.

This process became an intimate inquiry into (and experience of) the depths of waste, a neglected space of taboos (wastewater is often shit) that somehow also issues invitations. And it was interesting, because so much of the waste sounded so good! The sound of metal, plastic, glass, and even wastewater have their own timbres — sometimes in ways that were similar to traditional musical instruments, sometimes in ways that I had never heard before. And our treatment of waste, whether by hand or machine, has its own pulses and drives.

So “Testimonium” doesn’t come with a how-to manual. But it is an invitation to waste, to spend some time with it. To dive into the pools of wastewater, into the piles of shredded cars and busses. If my work can generate a kind of access to waste as opposed to furthering our alienation from it, then this new “awareness,” if you will, may equip us to take action. People who experience “Testimonium” might feel less alienated from waste. What they do with that experience is up to them.

KD: One of the most frequent questions I get when people find out about the substantial human and environmental costs of music is: What can we do about it? People seem to expect Hollywood endings. I try to resist providing easy answers — partly because of the assumptions about solutions that are hidden in the question. Often, when people ask what they can do to mitigate the human and environmental costs of music consumption, what they are really wondering is how they can go on consuming more and more but harming less and less. This is a form of solutionism that I think follows from a flawed understanding of the problem that we need to solve. I understand that you tend not to be asked the “what next?” question in relation to “Testimonium.” Rather, you might be asked about your own situated involvement in the world and your role in sonifying the issue of waste. I’d be interested to hear what you think about that.

JK: We have developed our so-called modern civilization over hundreds of years. While the extent of today’s forms of consumerism (whether goods or energy) must urgently be reconsidered, we are also to some degree trapped in what we have created. Most of us have blood on our hands from the mining and manufacturing that go into our phones and computers, yet it is not practically possible to do without such devices today. Everything happens in the online world of computers. It is where I edit my sounds, where I communicate with family and friends. But it is also where states and citizenships are enacted — everything from medical appointments to voting.

Over the past twenty-five years I have also extensively travelled the world recording sounds, performing live, and exhibiting. With the climate crisis, and now the shock that has followed with the pandemic, I no longer know if the way I lived before is sustainable or even possible. Yet I feel dependent on the life I have lived. Still, the pandemic has also shown that we can in fact change — and that we can do it fast. Although we’re trapped, we need to adapt.

KD: Maybe this is a difference in the expectations that are brought to writing and sound as media. But I’m also interested in an idea inherent in “Testimonium,” which has been described as looking back from an imaginary future or offering a form of archaeological witnessing for the future. What kind of relationship do you think your work invokes in relation to the future, whether in terms of the pragmatics of tomorrow or the promise of something unforeseen?

JK: Many years ago, I had the opportunity to work as an assistant for an archaeological excavation at an eight-hundred-year-old graveyard. I spent a whole summer digging up skeletons. In the graves I also found pearls and other beautiful things. That was where I learned that the midden, too, teaches us about our ancestors. What they threw out has a lot of value for us. In the same way, our waste will have a significant value for the coming civilizations that will try to learn about our moment.

I chose the title for this work about garbage because waste bears witness. Like it or not, trash tells the truth about our time. “Testimonium” is a way of giving voice to waste, without teaching it how to speak or telling it what to say. Those determinations will be made by future generations.