“Listening In” is a column dedicated to sound, music, and listening practices in contemporary art and its spaces. This section focuses on how listening practices are being investigated and reconfigured by artists working across disciplines in the twenty-first century.

Benjamin Piekut: Although sound has always been an important element in your art practice, I have the general impression that auditory processes were most pronounced in your early work. I am thinking in particular of Synthesis (1967) and Action Lecture (1968). Your investigations into perception and language took you further into video in the 1970s, and, though sound never disappeared, I wonder if it diminished in importance. Is my impression correct, or do you think of that period differently?

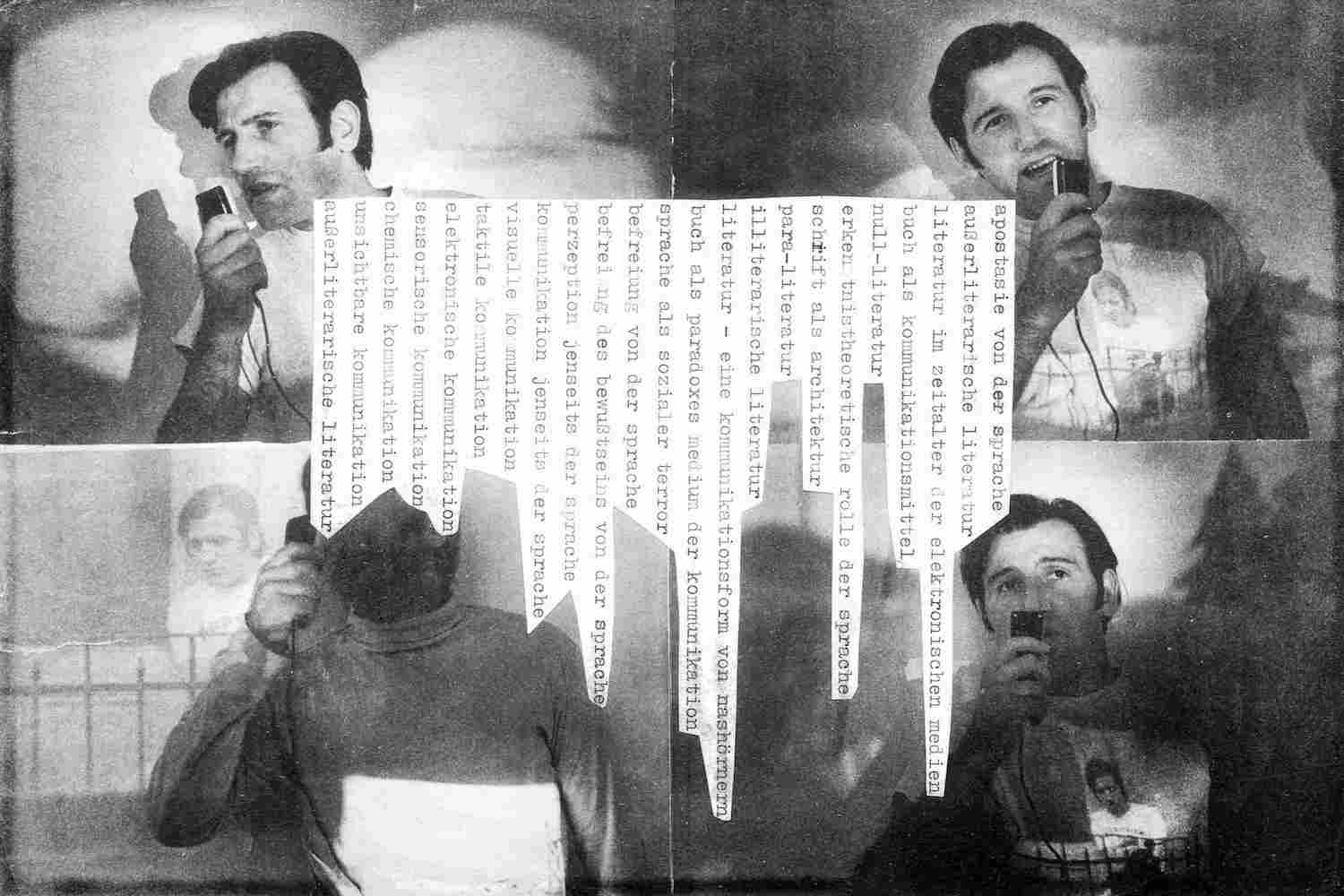

Peter Weibel: I think my interest in sound merely shifts in form and emphasis. As a young experimental poet, I was fascinated by the phenomena of alliteration and assonance, and the sound of spoken poetry in general. In 1964 I befriended the Viennese sound poet Ernst Jandl, who taught me about advanced jazz music and other sound poets such as Henri Chopin. Prior to the encounter with Jandl I was an ardent follower of musique concrète (I studied in Paris in 1963–64). Through studying musique concrète I encountered the Magnetophon. Thereafter, I devoted myself not only to studying the relationship between mouth and sound, i.e. oral sound poetry, but between Magnetophon and sound, i.e. technical oral poetry. I became a media poet and did experiments with linguistics and tape.

These experiments soon became controlled not only by the author but also by the audience, as in the works The Myth of 21st Century. The Event Field of Endless Rules (1967) and Action Lecture. Communication Breakdown (1968).

In both cases the audience could control the activation of different sound sources, such as tape recorder, film projector, record player, etc. By this approach, music slowly entered the field. Then I experimented frequently with sound in my expanded film projects. For example, in 1969, I created the first autogenerative sound screen, called The Magic Eye(Magisches Auge). On a transparent screen I had several light-dependent resistors (LDRs). I projected a silent film with optical patterns onto the screen and the LDRs transformed the light waves into electronic sound waves. Blackness created deep sound waves and bright light created high-pitched sounds. Normally, the sound comes from the projector, from the filmstrip. But here, the sound came from the screen.

So, you are right, sound was important for my poetic as well as for my cinematographic work. I can even say I thought of myself as an experimental poet, experimental cinematographer, and experimental sound artist. I published a “kiss anthology” on the radio in 1972: people could listen to a series of kisses that were announced kiss by kiss — for example, as a kiss between Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor or between Gary Cooper and Grace Kelly. Naturally, nobody could prove the veracity of the claim.

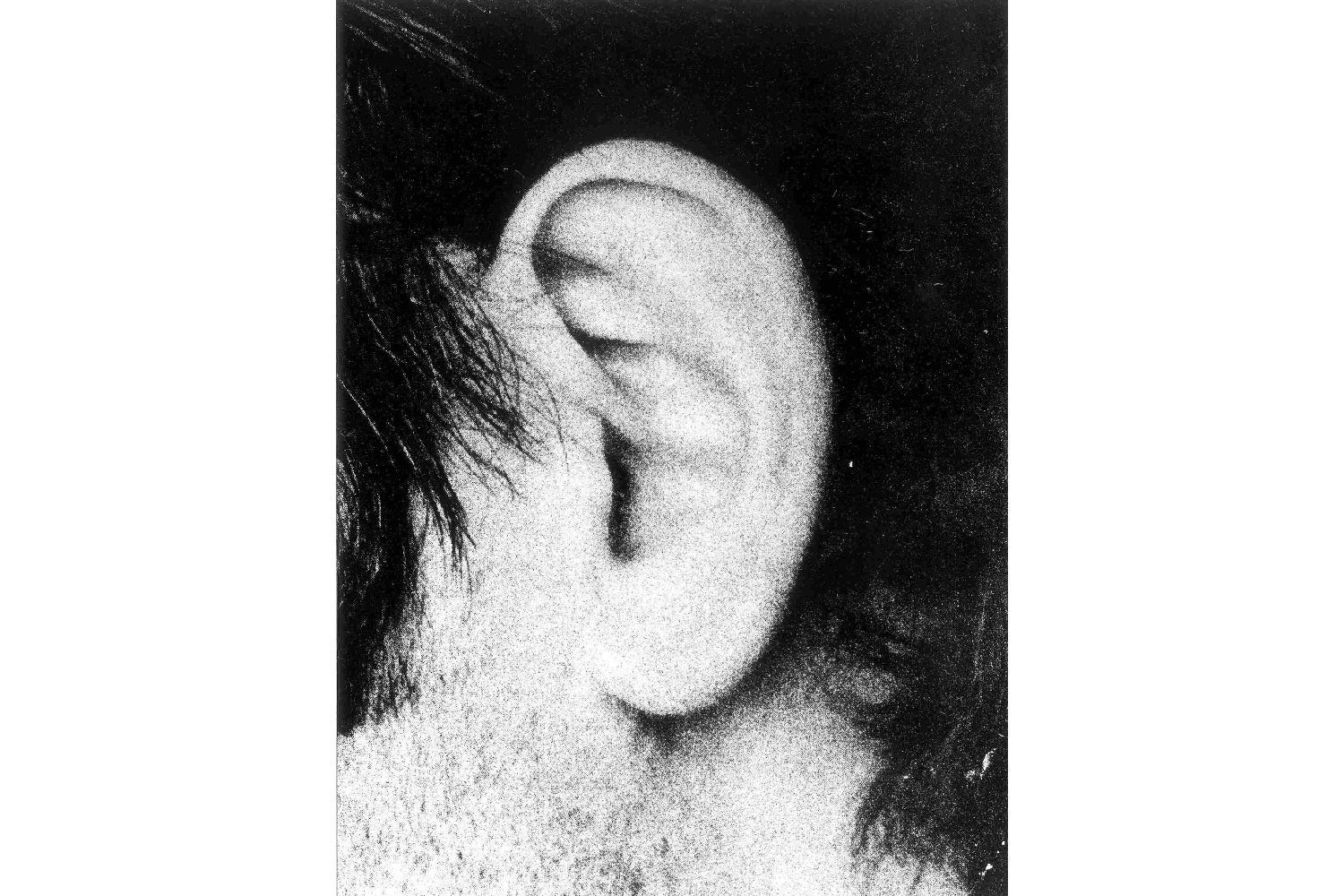

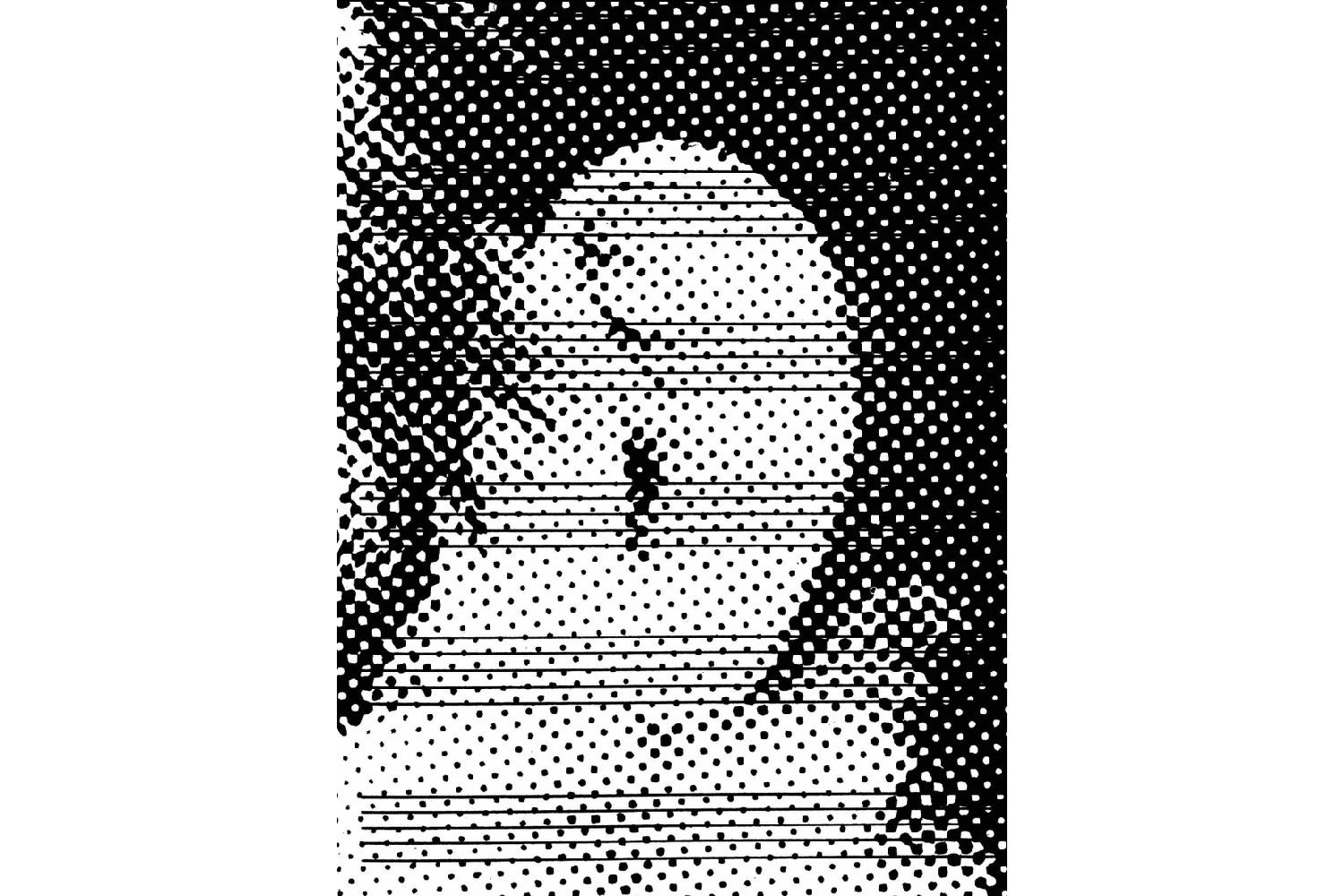

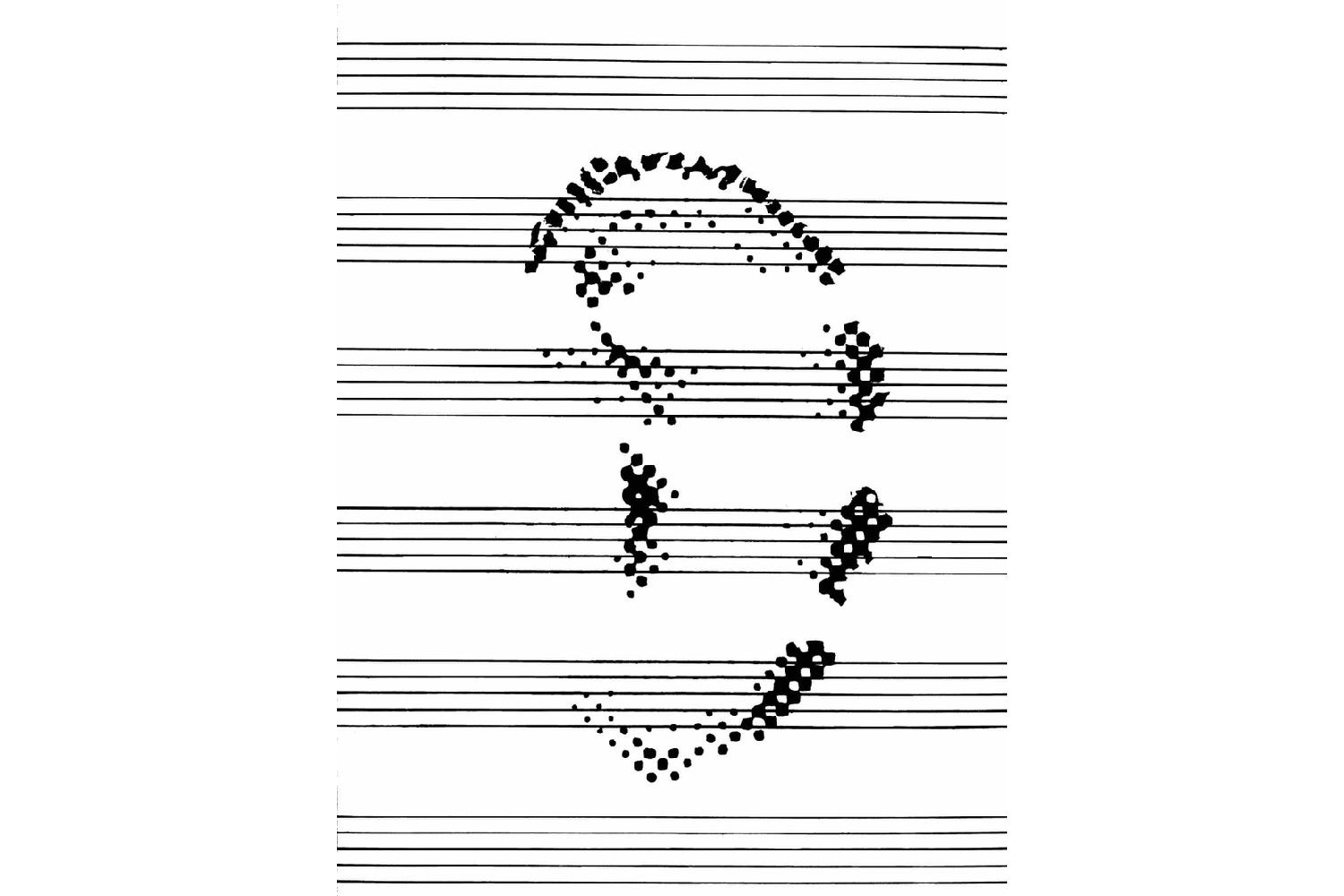

I was also influenced by movements in contemporary music. I was fascinated with graphic notation and made a lot of work in this direction myself: music just on paper. I used techniques of photographic reproduction and enlargements to turn the picture of an ear into a musical score in Transformational Music (1972). I also made a sound installation called Auditory Passage (Gehörgang) in 1979, wherein two very large ears on opposite sides of a wall formed a corridor to walk through and listen to a poem about hearing.

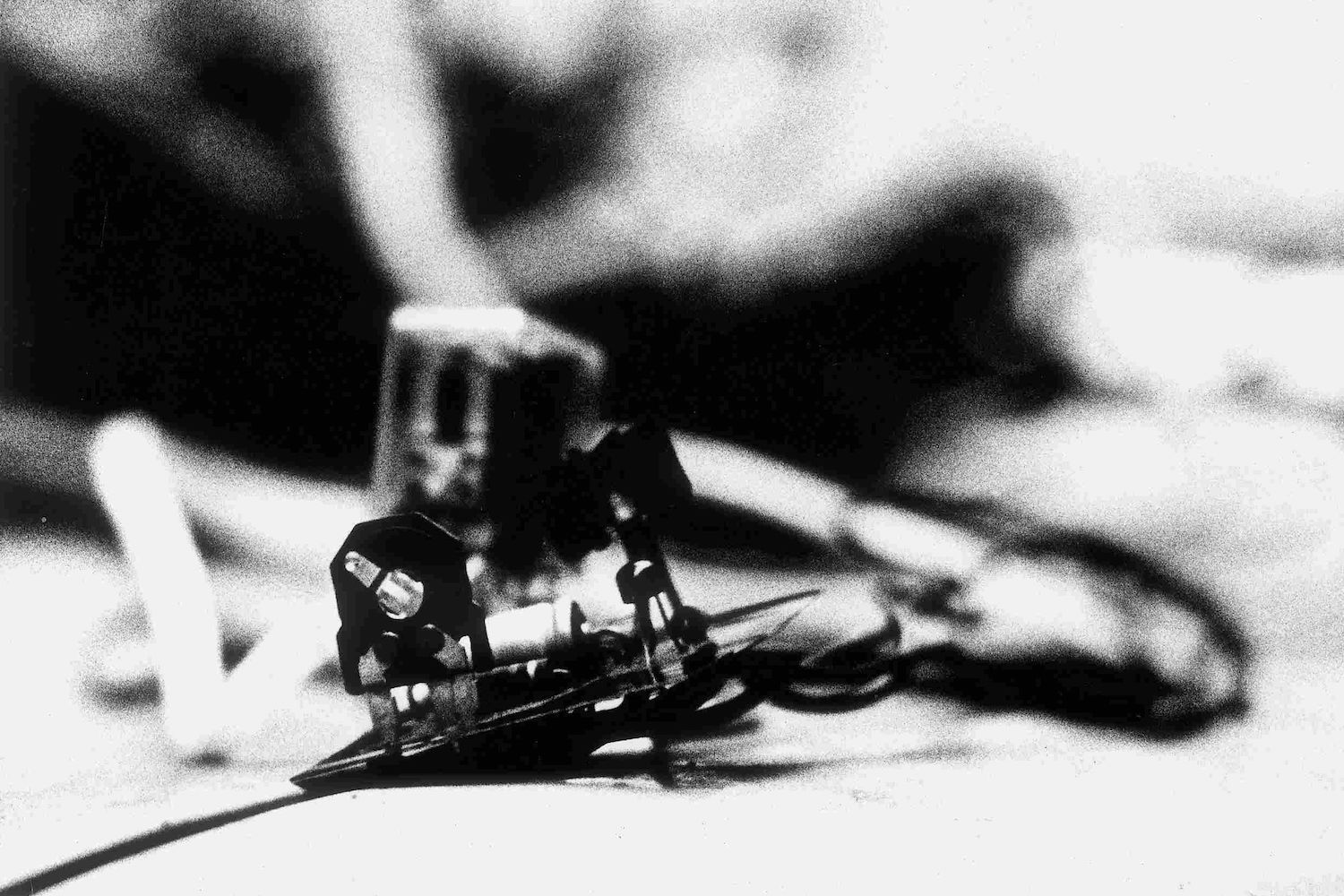

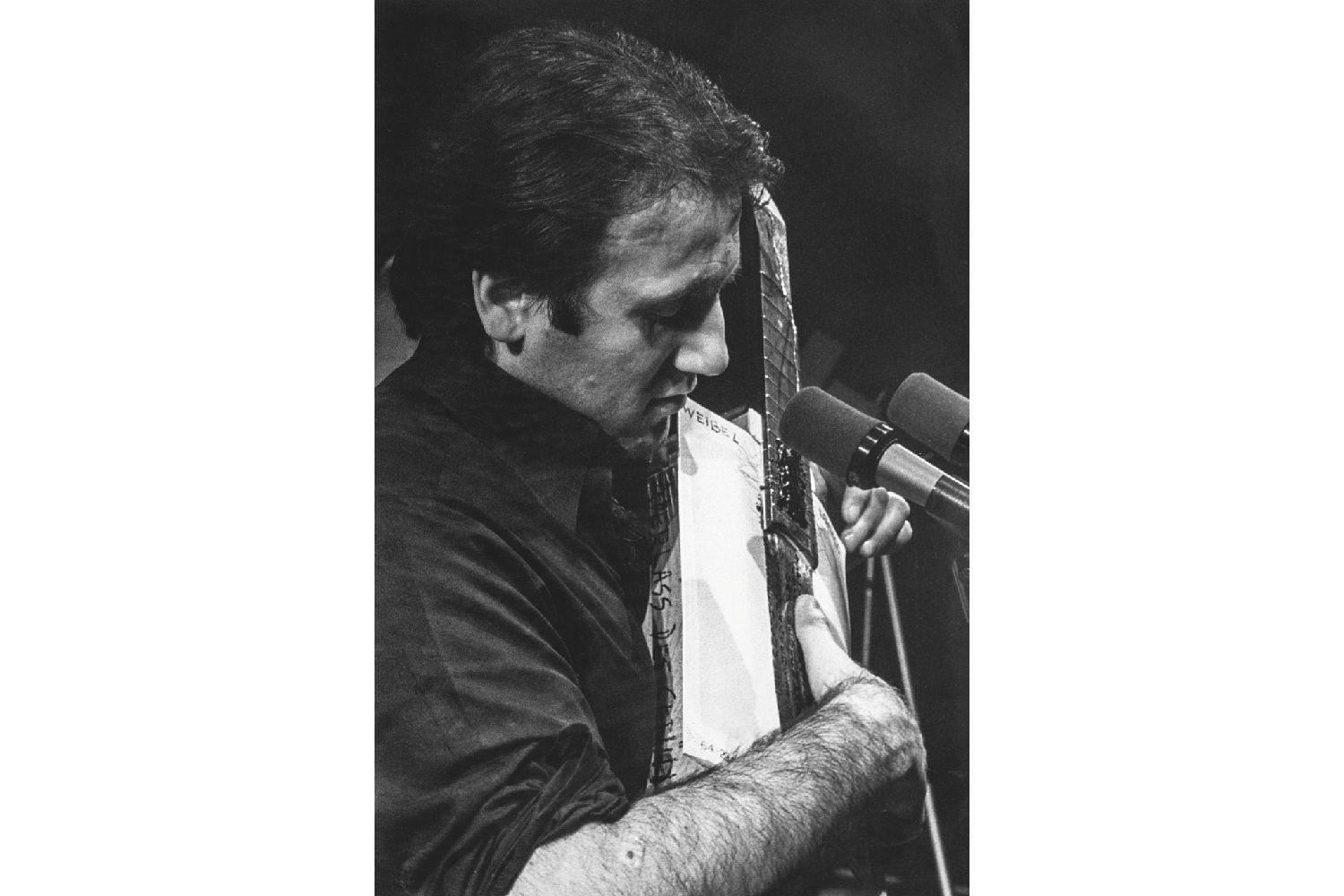

BP: In the late 1970s, sound came back into your field of action, but it did so in a generically formalized manner: in a band. When you founded Hotel Morphila Orchester, many other artists from “outside” of music were beginning to explore bands almost as if they were a distinct medium. Sound narrowed to music, and even further to a “popular” idiom. At the same time, a sculpture/instrument like Buchgitarre (1978) — which I believe you occasionally played in the band — suggests that you were also thinking about performance in a less formalized, or perhaps more experimental, way. What are your thoughts about this series of changes?

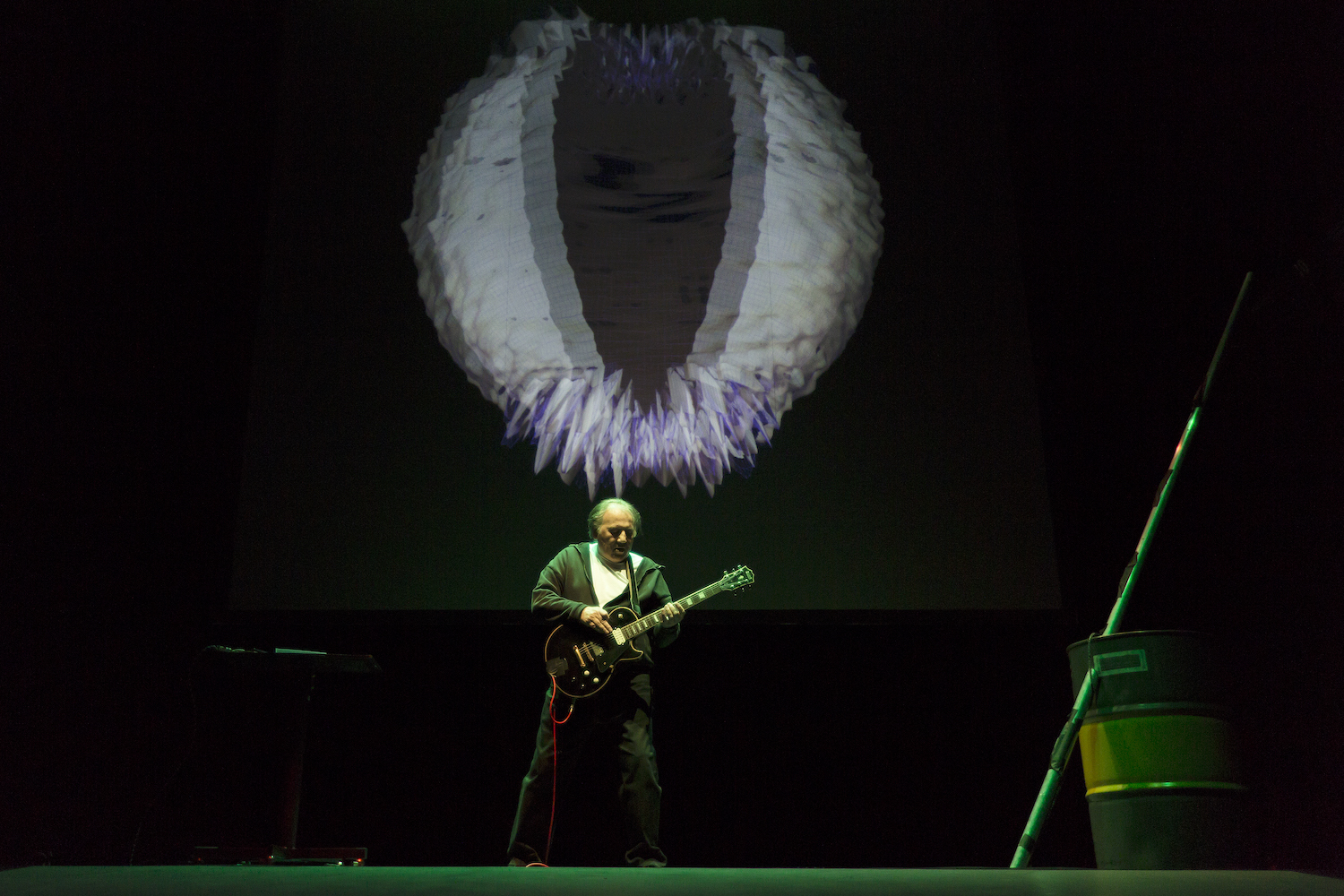

PW: Indeed, in the 1960s I was surprised by the quality of some sound experiments with the electric guitar, from Jimmy Page to Jimi Hendrix — and the rise of Kraftwerk and psychedelic bands like Guru Guru intensified my interest in experimental rock. I even created a show with Guru Guru (and other bands) called “Underground Explosion,” which I took to major cities such as Munich and Cologne. Playing to thousands, Underground Explosion was a mix of actions by myself and Valie Export, theatrical performances in some of my expanded cinema experiments, and advanced underground rock. Ten years later, my desire to continue these experiments was so strong that I founded the band Hotel Morphila Orchester in 1978 with painter Loys Egg. There was a kind of explosion, as you say, of visual artists invading pop music. My impulse was to write avant-garde lyrics but embedded in the idiom of advanced pop, even using lyrics by William Shakespeare and Friedrich Nietzsche. I liked the idea that people would come to a concert to listen to pop music, somehow lured by the promise of pop music, but actually hear advanced poetry. Around the same time, with the return of painting around 1980, the art world grew reactionary and academic. Rock was my protest medium. But in the beginning, the music was embedded in performance art: our first appearance was in Lenbachhaus in Munich, in 1979, as part of a larger performance.

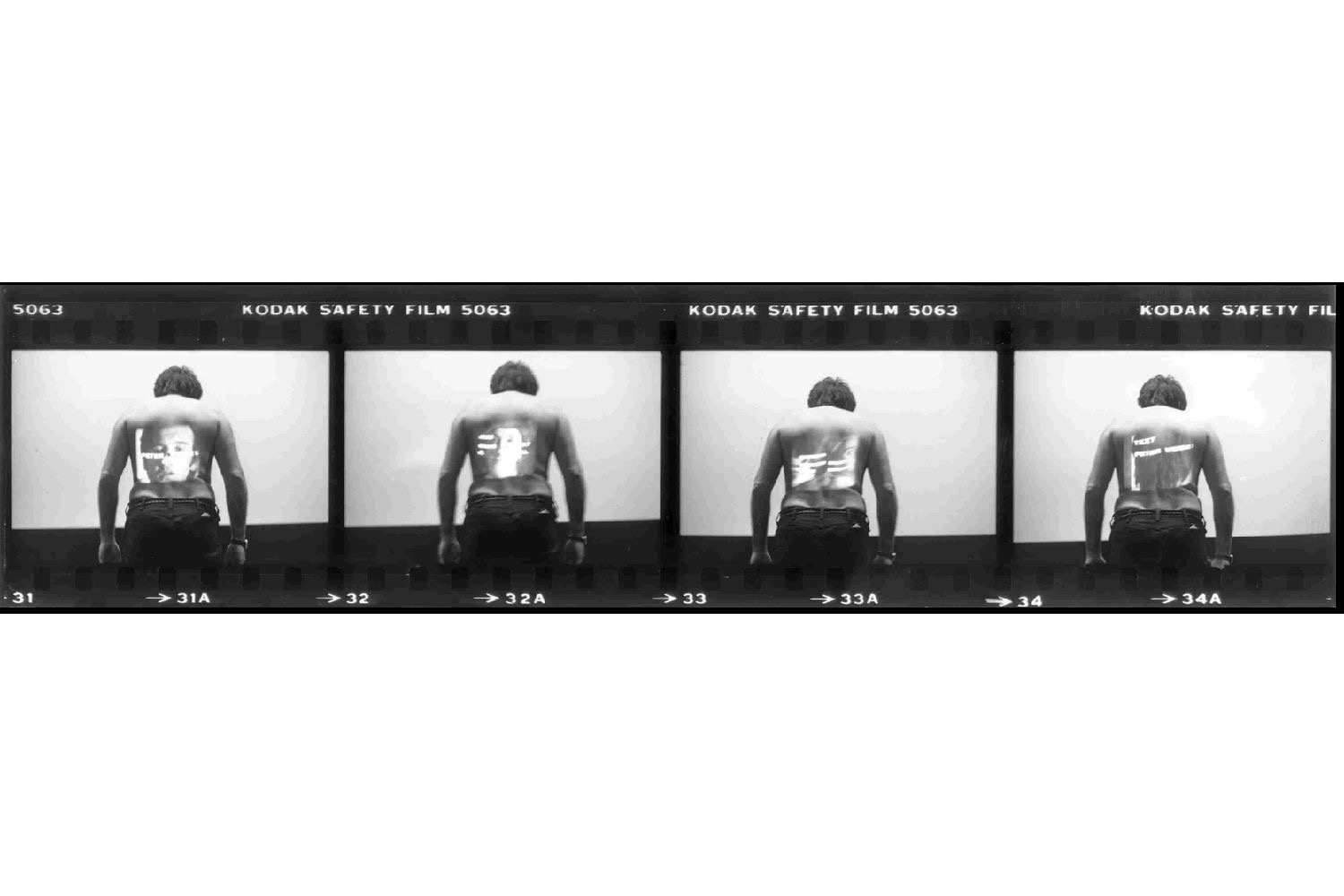

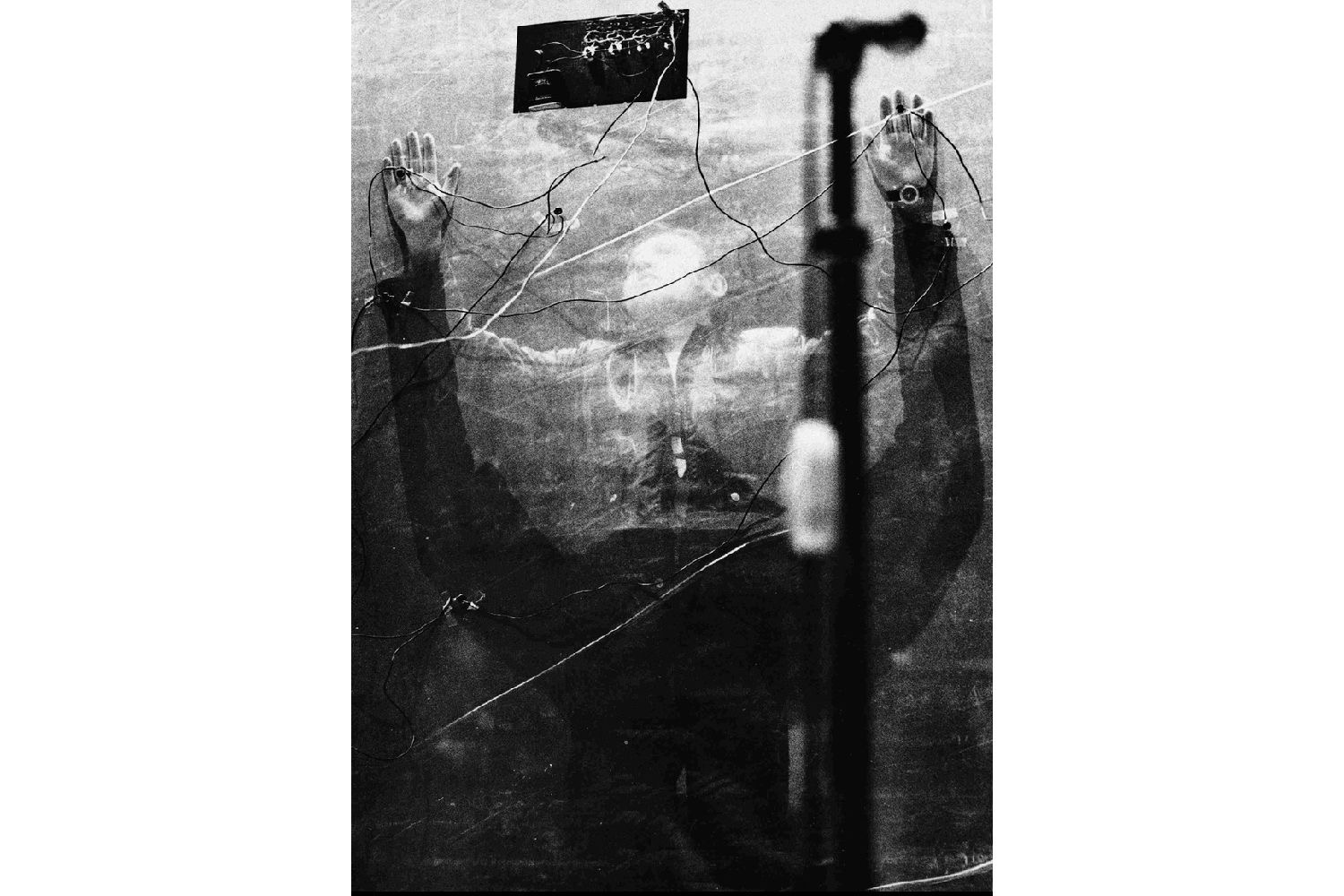

In 1979, I was experimenting with tape machines, telephones, and video. For example, I pointed one camera at my naked chest and a second at the instrument of the lead guitarist. As I plucked hairs from my chest, the guitarist simultaneously struck his strings. Both images went through a mixer; on a huge screen, the audience could see me “playing” my chest as a guitar and the real guitar played by my bandmate. He created a horrible sound of my pain, tearing the hair of my chest. I made also chemical experiments with my body. I rubbed a transparent chemical on my face and another invisible, chemical liquid on a knife. When combined, the two would react by turning bright red, so when I took the knife and touched my face it created the illusion that blood was dripping off my face. Accompanied by hellish noise, this moment terrified the audience. These video performances had been very extensive and expansive. Therefore, slowly we dropped this kind of performance element, using specially created microphones or specially created instruments such as the “Buchgitarre,” which, indeed, I sometimes played on a stage.

I myself preferred this kind of “less formalized and more experimental” performance, but organizers and the public put us under increasing pressure to become more like a normal band. Therefore, after several years Hotel Morphila Orchester came to an end. I created a new band called Noa Noa and, in 1984, I wrote a media opera called The Artificial Will (Der künstliche Wille) for the opera house in Linz on the occasion of the Ars Electronica festival.

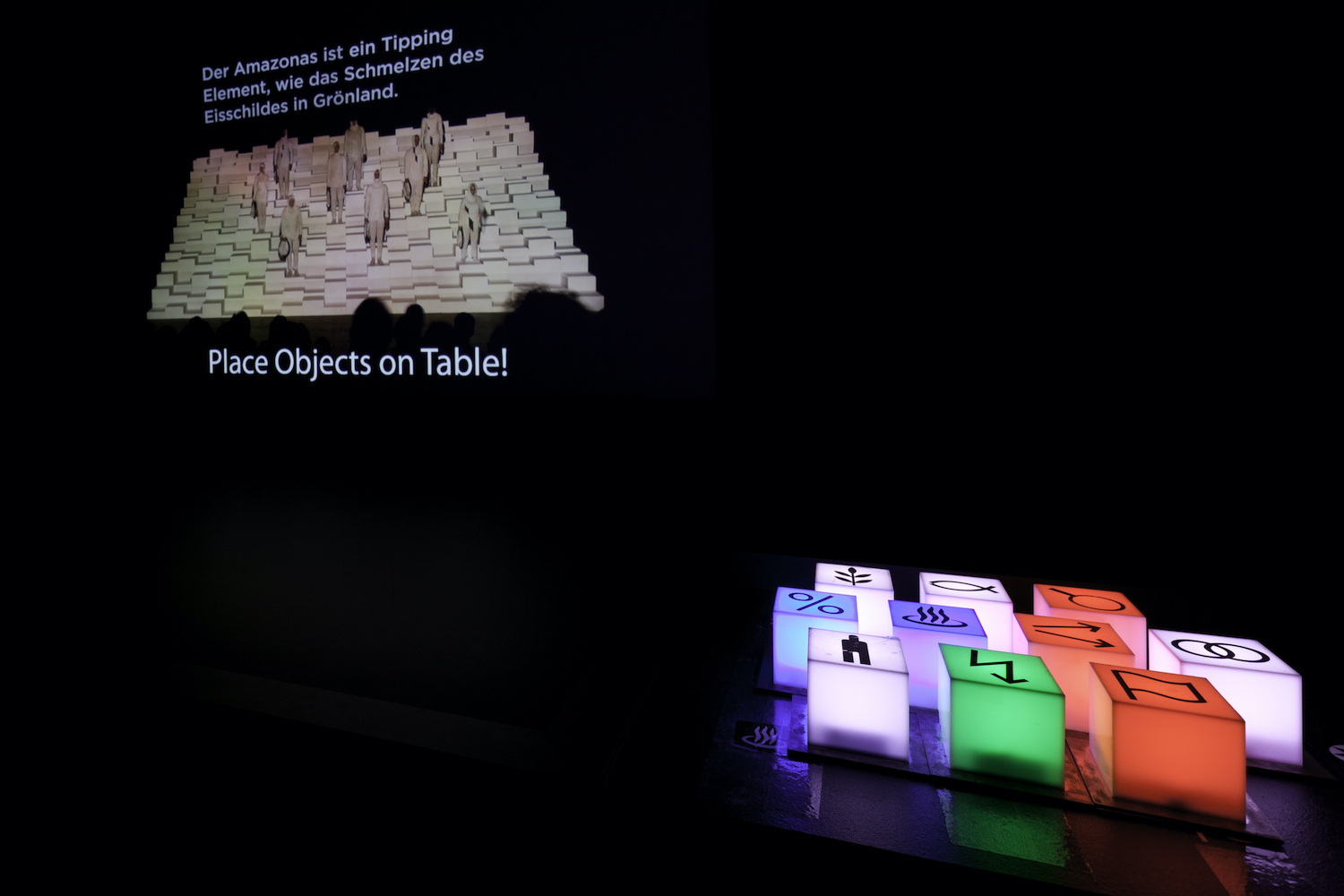

This was one of the first multimedia operas in Europe with an electronic stage. Noa Noa played onstage for the whole opera. I acted and sang, performing with multiple objects and technical devices, multiple cameras, and sophisticated sound gadgets. Sometimes one or two women came onstage to interact with the screen and some objects. This interest in the new form of multimedia opera remained with me, therefore I made several more: Voices of/from Inner Space(Stimmen aus dem Innenraum, 1988), Amazonas (2008–10), and Origin of Noise – Noise of Origin (2013). All of these operas were based on new instruments and sound devices and electronic music, including digital music.

BP: In its post-disciplinary stages, contemporary art and performance required new kinds of spaces for exhibition and presentation. The white cube, the concert hall, the proscenium stage, the cinema — they didn’t work anymore. The ZKM, which you have directed for more than twenty years, is a prime example of this new kind of institutional space. What was it like to prepare your show “Respektive Peter Weibel” for the ZKM, entwining your own career with the history of that institution?

PW: You are absolutely right, the white cube, the concert hall, the proscenium stage, the cinema, they don’t work anymore. They don’t have the equipment for the new music, they don’t have the competent people for the new music, and they can’t provide the spaces for the new music. Therefore, new music and sound art are in exile in the museum. The ZKM is the only museum in the world which collects electronic music, new music, and sound art. We have thousands of pieces collected and accessible. In our present exhibition of the collection, “Writing the History of the Future” (2019), we have dedicated a huge area to sound art. We are a model for the future. I am sure, in the future, sound art will be part of presentations of museum’s collections. When the curatorial team of ZKM prepared for the show “Respektive Peter Weibel” (2019) it was clear that the team would not only show my linguistic and filmic sound experiments but also dedicate spaces to Hotel Morphila Orchestra, to my media operas, and my digital sound installations.

BP: The catalogue for your magnificent 2012 show, “Sound Art: Sound as a Medium of Art,” has just been published by the ZKM and MIT Press. It is a landmark publication. Among its many virtues is its collection of essays about the history of sound art around the world: UK, Germany, Russia, Turkey, China, Japan, Australia, North America, and Brazil. How do you understand the relationship of the ZKM — and its own, local genealogies — in relation to the global contemporary formations surveyed in the catalog?

PW: The founder of ZKM, the art historian Heinrich Klotz, had the vision not only to collect contemporary art and media but also to establish the research Institute for Music and Acoustics (IMA) and the Institute for Visual Media (Institut für Bildmedien). So from the beginning, ZKM was a place where advanced contemporary electronic music was performed continuously. ZKM has many studios, as well as one of the best concert halls in Germany. The institution has a program of invited composers in residence who, with the technology available and the help of our staff, can create new work that is then premiered at the ZKM. We award the Giga-Hertz-Award to outstanding composers such as Pierre Boulez, Curtis Roads, Pauline Oliveros, Éliane Radigue, and Laurie Anderson. The ZKM understands itself as a global center for contemporary music through its publications, editions, symposia, concerts, etc. We are indeed in a permanent dialogue with composers around the world. Therefore, it was clear that the catalogue must give a survey to global contemporary sound art.

BP: The Sound Art catalogue is full of images of wires, cords, tape, loudspeakers, LPs, and screens. One cannot but view this detritus of twentieth-century consumer media in a longer history of ecological change and the coming climate catastrophe. I wonder how you hear this history in the context of environmental collapse and the rest of the twenty-first century?

PW: Indeed, the future of sound art is uncertain. I admire deeply the civic achievement that has conserved, preserved, stored, and restored the art of painting for hundreds of years. This is an incredible achievement of our society. But this is precisely what I ask from our actual society: to make the same effort to conserve, preserve, store, and restore the audiovisual culture of our time. Naturally, this task is much, much more complex because painting and classical sculpture are technically very low, stable material. Our contemporary audiovisual art is technically very complex, and changes its software and hardware every ten years. Therefore, it is an enormous challenge how to save film, video, new music, sound art, performance, digital art, for the centuries to come. If our civilization, our cultural institutions, educational systems do not make a nearly incredible effort to save this new world of electronic media, then this culture will disappear. I am trying to turn ZKM into a Noah’s ark for media art. I deeply desire that in five hundred years, people can see, listen and experience at ZKM the world of media art as one of the most important contributions to humankind on Earth.