Post-Pandemic Imaginaries is a new column by Pier Luigi Sacco that explores a series of new scenarios by various artists who re-imagined a new collective consciousness after the past lockdown.

Painting is all about misleading the viewer nowadays. The painter’s tactics are to inspire the viewer to be condescending, leading her/him to think s/he is too good for that picture. It’s just a picture like many others, and in the end, what else could it be after centuries of great painting? So you let your guard down and give it just one more glance before looking away. And this is where good painting strikes. Wait, what? Now there is that detail you didn’t get earlier, and, you know, you didn’t expect that. It is really intriguing. What else is there? You start looking at the painting for real, and the game begins.

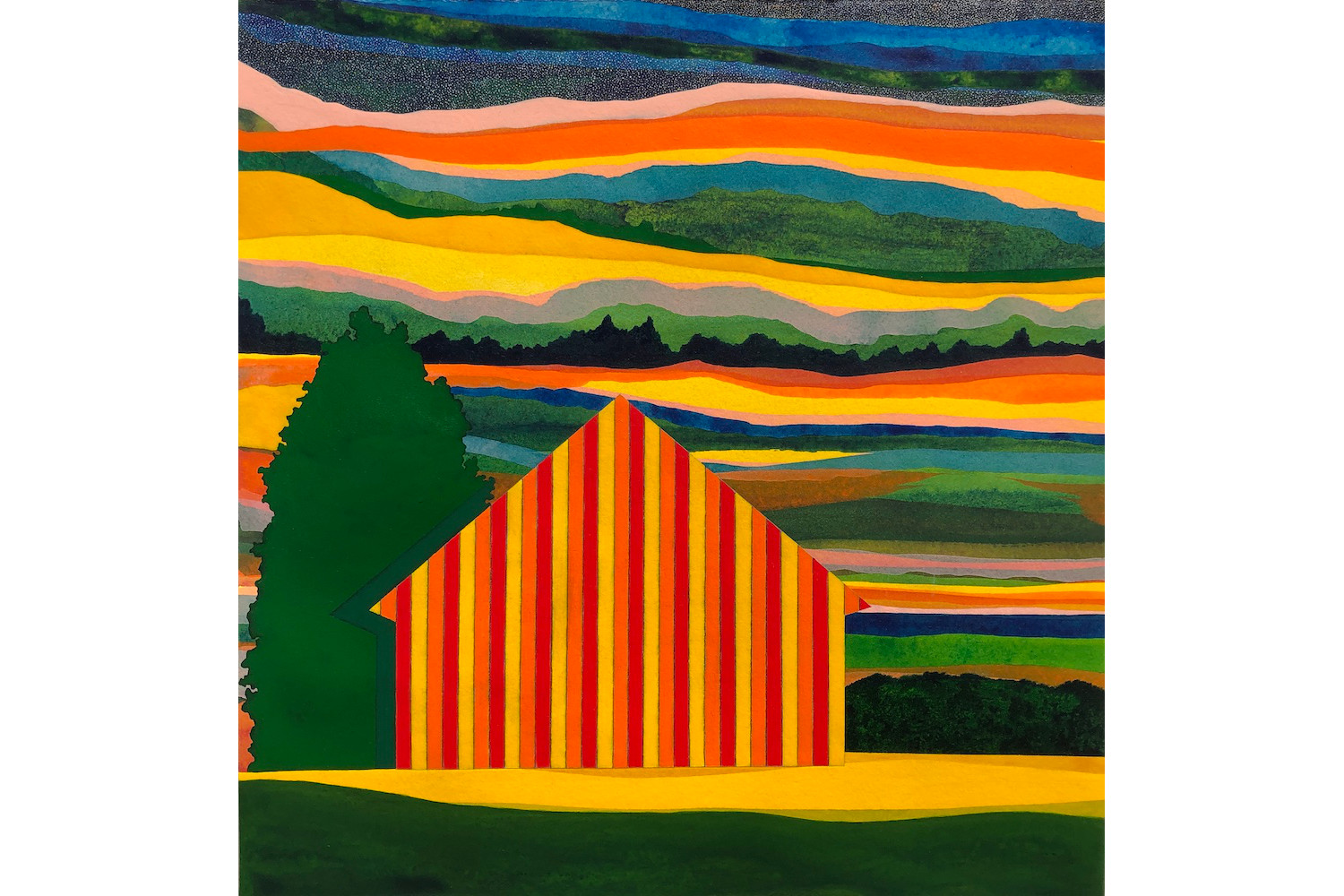

In this sense, James Isherwood is a master of deception. His graphic imagery, with its hyper-saturated colors, seems tailor-made to grab our sight and take it down a very familiar alley of pleasurable colorscapes, dangerously flirting with illustration art. Its strategy of play apparently shuts down the art viewer’s gaze, inviting us to a more elementary, hedonic form of access. But, as in Gestalt phenomena, in which a sudden shift in perception unexpectedly reveals a brand new pattern where we thought we’d seen everything, this is the moment when Isherwood’s painting kicks in. His apparently familiar images are full of incongruous, unsettling details despite their prima facie innocuous look. You finally realize that underneath the glossy surface of the image, another, skillfully concealed layer has been patiently waiting for your eyes and your mind to focus on this whole time.

The first unsettling element is the absence of human traces, combined with the presence of strange architectural artifacts that, despite their obvious allusion to stereotypical built forms, are clearly not inhabited — or possibly even inhabitable. They are, rather, impenetrable monads, whose relationship with the surrounding natural environment is both entirely necessary and entirely obscure at the same time, such as in Rise (2019). The natural environment itself, once one looks more closely, reveals a composition of “tiles” like windows onto parallel realities, equally uninhabited, distant, and indifferent to our eye. The physical matter of the landscape is, in turn, a montage of decorative patterns and graphic textures like those commonly found in architectural renderings, revealing an artificial, fictional nature. Everything we see is therefore a deceit, as hinted at by Figment (2018). The appearances confound us, and yet they are strangely invigorating. Isherwood’s paintings are promises of a “great beyond,” a prospect that moves us deeply in this brave new world of claustrophobic lockdowns and constrictions to mobility. But such a beyond is not just made of quiet, enchanted, unpopulated expanses, but of expanses within expanses, as in a fractal progression in which, by visually digging in, we find a door to another universe and then a door within the door, endlessly. It is a promise of freedom, but maybe also a subtle trap. It’s the unknown in familiar guise.

Going through Isherwood’s oeuvre, the viewer starts to recognize a visual grammar. There are recurring elements: not only the “houses” but the reflecting pools, the vegetation, the layered hills and mountains, each of which functions as a structural element with a proper yet undisclosed task. We seem to witness the visual equivalent of listening to a spoken language we have not mastered. We recognize the sounds but not the meanings.

While studying Isherwood’s work, I could not help feeling a strange familiarity, and only after a while did I come to realize what it was. His paintings reminded me of Giorgio de Chirico’s Piazze d’Italia. In de Chirico’s metaphysical paintings we find a captivatingly analogous articulation of a visual grammar through the endless recombination of a small number of familiar elements, entirely decontextualized from their original function or social meaning, resulting in an otherwise familiar scene that appears intensely, almost threateningly, enigmatic. De Chirico’s imagery is a complex fusion of disparate built forms, ranging from Greek-Roman sculpture to building facades and factories, which together evoke a phantasm of the “Italian” square, reinvented as a theater of silence and stillness, as opposed to the bustle and energy of “real” Italian public spaces. The atmosphere of these spaces exhales an otherworldly sense of suspension that surprisingly resonates with that of Isherwood’s paintings — such as in Ascension (2018) — while at the same time wielding a somewhat opposite symbolic alphabet and a profoundly distant system of cultural references. If de Chirico’s “squares” probe the uncanny in urban environments, Isherwood’s “landscapes” carry out a similar operation in nature. De Chirico’s metaphysics are unequivocally built on European, and more specifically Mediterranean, visual and cultural sources, just as Isherwood’s “neo-metaphysics” are unquestionably American. But they share unexpected commonalities, possibly because of a shared seismographic attitude that captures a mounting sense of instability and unrest that characterized both the early years of the past century as well as those of the current one. The only literally common element of the two symbolic systems are the pools, entirely opaque and enigmatic in de Chirico yet reflective in Isherwood, where they sometimes mirror trees that do not exist in the surrounding space (thus suggesting the existence of further, unnoticed routes to parallel realities), as in New Understanding (2020). This tenuous common nexus suggests how the two systems are in fact dialectical opposites.

De Chirico’s squares confine the ideal city in the realm of an unreachable “beyond,” where human figures are nothing but distant, still forms — urban furnishings that share the same definitive immobility as the statues that adorn the square. Even in the rare instances in which a moving human figure is represented in the scene, it appears to be equally consigned to the eternity of a frozen moment, in which movement remains more a speculative possibility than an actual option, no different than the puffing trains on the horizon or, in the later “Partenze” series, the boats set to sail upon a sea whose sight is inescapably denied by a wall. There is a sense of loss, deprivation, and, at the same time, burning nostalgia for an elsewhere that is free from human tumult. “Humankind cannot bear very much reality,” says T. S. Eliot in Burnt Norton, and this is why most of what happens in de Chirico’s metaphysical theater is concealed from our sight. In Isherwood, a similar theater of silence and stillness takes place (as eloquently suggested by Fragrant Silence, 2018), but here, the beyond of which we are offered some spare fragments is a sort of human-less Walden. To the European nostalgia of the ideal city as the hallmark of harmonious living, there corresponds the American nostalgia of nature as an inner temple of self-reckoning, as convincingly argued by Leonardo Caffo in Il bosco interiore [The Inner Wood].1 But again, these are just our projections on a reality we do not comprehend. We are not playing the game. We are spectators, and the rules of the game escape us. De Chirico’s squares are not squares, just as Isherwood’s landscapes are not landscapes. What are we looking at then?

The essence of metaphysical painting is to invite us to ask that question again and again, while at the same time frustrating any attempt at a response. We do not know what we are looking at. We can only keep on collecting fragments and traces, painting after painting, maybe patiently waiting for that single moment that Eugenio Montale describes in a famous poem in Ossi di seppia [Cuttlefish Bones]:”2

Maybe one morning, walking in dry, glassy air,

I’ll turn, and see the miracle occur:

nothing at my back, the void

behind me, with a drunkard’s terror.

Then, as if on a screen, trees houses hills

will suddenly collect for the usual illusion.

But it will be too late; and I’ll walk on silent

among the men who don’t look back, with my secret.

Maybe these images are just screens covering the vertiginous void that we need to elide in order to continue existing. But maybe these are something entirely different: prohibited sneak peeks at a reality that does not need the human gaze to exist, such that they concede to us only to mock our illusion of control and centricity. Isherwood’s rejuvenation of the metaphysical in an uncanny natural setting shows us a potential post-pandemic world in which the human is no longer contemplated — where traces of its existence are reabsorbed and seamlessly reappropriated by nature like in Slumberland (2017), to be re-inflated from within by a vital principle that prescinds from us, and whose likely signature is the impossibly intense, metaphysical illumination that emanates from within some of Isherwood’s “houses,” like in Waking Dream (2020). The Yearning Season (2018) is the title of one of Isherwood’s most powerful paintings, but that yearning is not ours. We will never have access to that vital principle, yet we long for it so much. The time has come to redefine our ambition to be the owners of the reality we live in. We are guests, and we have possibly been gently invited to make a silent step back and quietly stand by The Edge of Forever (2018–19). A forever that has possibly just begun.