Paljassaare means “naked island.” The peninsula visible across the water from Kai was called that because there used to be no trees on it (and not on account of its nudist beach). It is now densely wooded in places, and home to numerous bird species that inspired the exhibition’s soundscape: a recording of three pieces dedicated to as many birds from Olivier Messiaen’s Catalogue d’Oiseaux (1956–58), performed by Estonian pianist and ornithologist Peep Lassmann. For A Collection of Wandering Matter (2016–19), displayed on twin wooden platforms supported by metallic rods, Triin Loosaar has combed Tallinn’s beaches — including the ones at Paljassaare — in search of unusual, mostly manmade objects polished and purified by waves, sand, and wind, which she then arranged into neat grid-like patterns.

About a year ago, while researching an episode of his ten-part “Leviathan Cycle,” Shezad Dawood explored Paljassaare on walks with architectural historian Robert Treufeldt, who has made a layered map of the peninsula, attesting to its past as a military ground that frequently changed hands before its recent conversion into a water treatment plant and a thriving nature reserve. The artist was particularly drawn to a coastal artillery battery built for the Imperial Russian Navy in 1915, featured in an archival black-and-white image that he had screenprinted and painted on linen dyed using locally sourced algae in collaboration with smart-textiles designer Kärt Ojavee and students from the Estonian Academy of Arts. The large textile diptych, titled Coastal Artillery Battery, Paljassaare, 1915 (2020), ushers the visitors into the main exhibition space like a theater curtain.

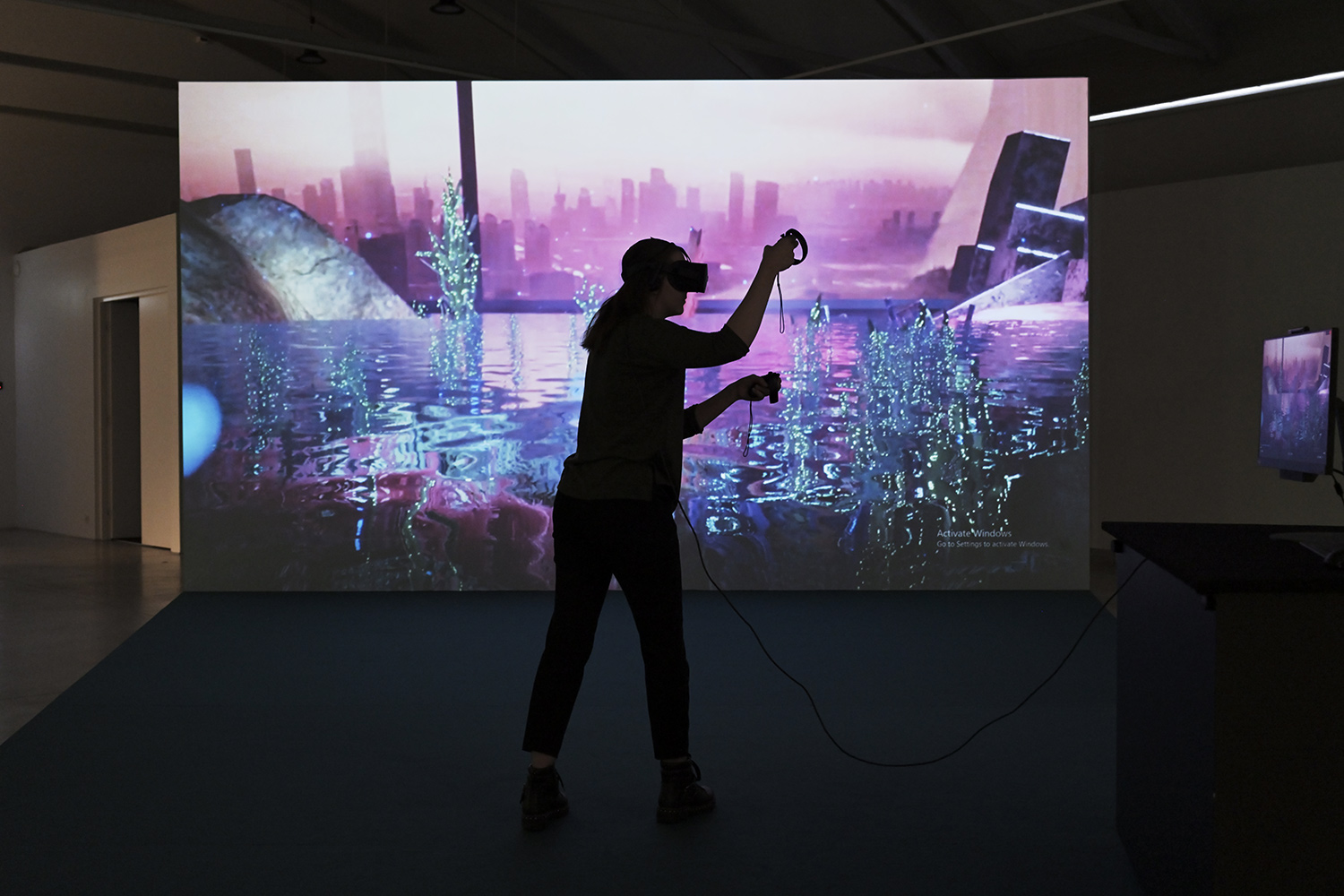

Paradoxically titled The Terrarium (2020), the VR work at the heart of the show imagines a seaside community three hundred years from now, somewhere along the connected Baltic and Kent coastlines, entirely submerged in water and inhabited by a hybrid marine creature — reminiscent of Ichtyander in the 1962 Soviet sci-fi classic Amphibian Man — as well as human-cum-animal pirates clad in black futuristic outfits worthy of Star Wars. The viewers’ hands and feet are transformed into crab claws and tentacles that they use to move about, the better to convey the entanglements between human agency and nature that the exhibition as a whole explores. In a climactic moment, depending on whether one chooses to look at the marine monster’s head or feet, one is presented with an alternative fate. Cutting-edge though it may be, The Terrarium is not entirely convincing as an artwork nor satisfying as a viewing experience, perhaps due to the trite nature of its futuristic imaginary.

This does not, however, detract from the interest of the constellation of objects presented alongside it and loosely connected to the themes The Terrarium addresses. Informed by his exchanges with the Australian coral specialist Madeleine van Oppen and her pioneering research into how coral can adapt to climate change, Dawood’s bioluminescent Hybrid I (2020) sculpture is a thing of beauty. Equally alluring are microbiologist Kai Künnis-Beres’s light boxes presenting green-tinged blown-up shots of microplankton and algae from the Baltic Sea. Made with a mix of organic and manufactured materials, the whimsical tools, nets, sails, and sundry clothing items designed by Ojavee recall the haptic nature of the VR work. Relaxing Mittens (2020), my personal favorite, sadly couldn’t be put to the test.