This conversation took place in May 2020. The text was originally published in Flash Art no 349 Estate 2020 – Italian edition.

Eli Diner: Thinking about the rapid changes of the current moment, I want to begin by asking about the role of time — specifically historical time — in your work. On the one hand, it is very much engaged with the present, scrutinizing the commerce, material culture, technologies, taste, class, ideology, and politics of today. There is also, of course, a futurological dimension, the sci-fi aspect. But then, at the same time, there is another thread that looks to the recent past (e.g. Crying Games). All of which in my mind amounts to a project of historicizing the present.

Josh Kline: As consumers, capitalism grooms us to live in the present. Contemporary electoral politics — especially as practiced in the United States — and contemporary twenty-four-hour news media also try and trap our imagination in the present. The past and future, history and long-term imagination, are all obliterated or obscured — crushed by short-term thinking. William Gibson has begun calling the combined onslaught of catastrophes — ecological, pathogenic, military, economic, etc. — that will come raining down in the twenty-first century “The Jackpot” — a slot-machine future that comes up all skulls. Once you see the growing world crisis gathering momentum around us, it’s hard to avoid asking where today’s conditions lead. Boomers may only have a few years left among us, but the generation entering adulthood now will see most of the century. For people who have a strong chance of being here mid-century, this is personal. As an artist, I’m equally as interested in describing and depicting our own era as I am in speculating about where it might lead. I’m not fixated on realism. My work is firmly situated across the border in the world of fiction. Grappling with how people in the future will view our present when it becomes their past is a very useful exercise — especially for Americans. The present moment will end and become something else.

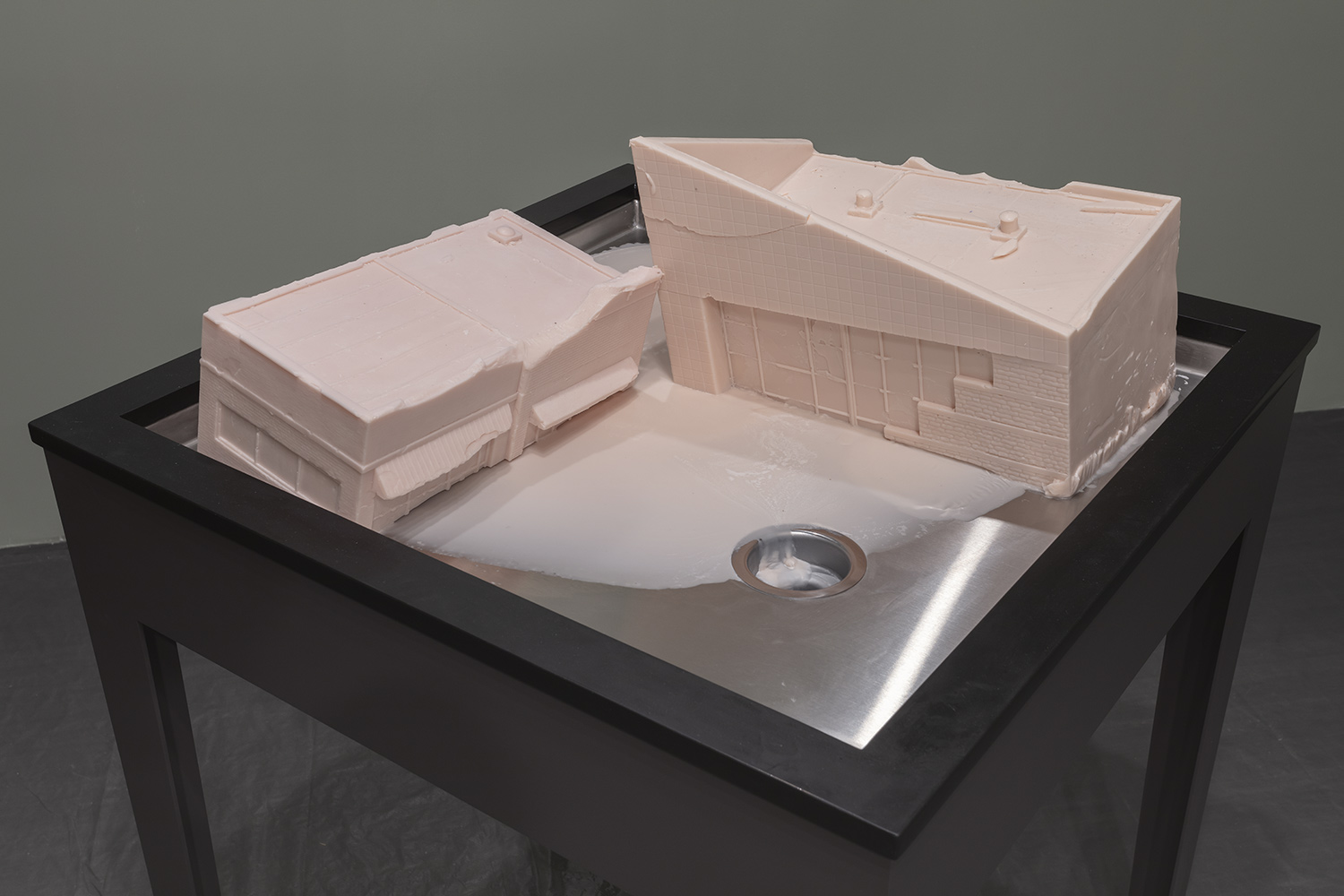

ED: Your show “Unemployment” comes to mind — actually it has come to mind quite a bit recently, as we plunge into depression and see growing mass unemployment. There you had 3-D-printed hyperreal sculptures of laid-off workers, dealing retrospectively with the impact of the Great Recession. The show also included these ads for UBI that were almost relics of the future. This offers a glimmer of optimism, I suppose, though there is more commonly, I think, a dystopian strain in your work — certainly a show like “Climate Change.”

JK: “Unemployment” is the second chapter in my larger cycle of installations about the twenty-first century — which at this point will probably be called “Extinction Story” — my “Cremaster.” Originally the larger cycle was meant to be half in hope and half in shadow. The first two chapters, “Freedom” and “Unemployment,” would be dystopias, the final two chapters would be utopias, and in the middle would be a project about climate change that would be the inflection point between the two sets of possibilities. As the world’s politics, economics, and ecology tip over into chaos I’ve become increasingly pessimistic and so has the cycle. At the cycle’s end, though, there will still be two chapters that imagine radical utopias. So, some optimism still remains, even in the middle of this.

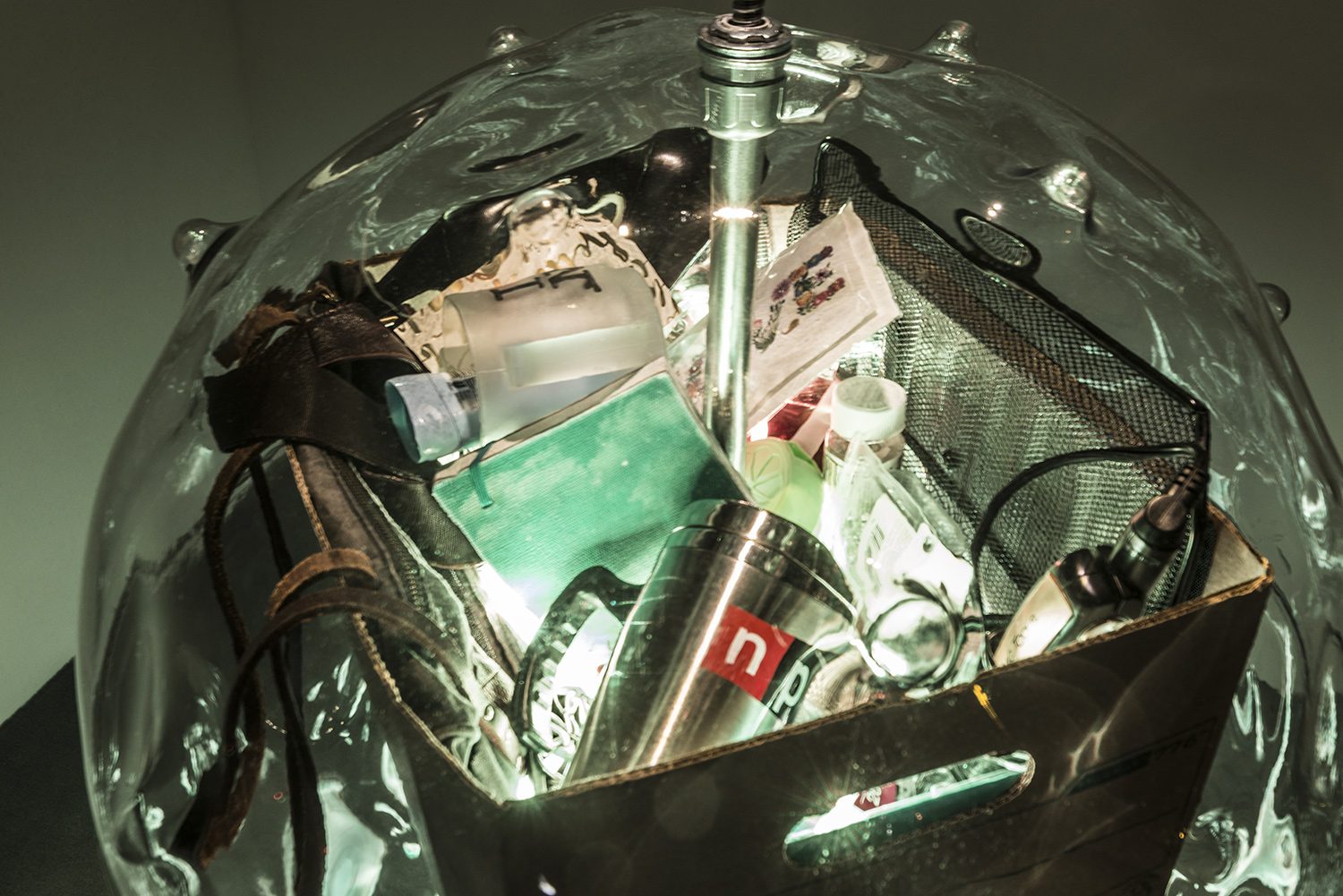

“Unemployment” was the first part of the cycle that was explicit science fiction, and not set in the present or the past. Those sculptures of unemployed workers I made in 2016 are portraits made from photographic 3D-scans. I chose the subjects I wanted to work with based on middle-class professions that automation and AI were predicted to wash out to sea in the next couple decades — lawyers, accountants, administrators, secretaries, bankers, certain kinds of journalists, etc. Looking at what had happened up until 2016, the historical parallels with the early twentieth century are impossible to miss — a hegemonic power living beyond its means, large-scale income inequality, the decimation of safety nets, a global financial system collapsing, an irresponsible and greedy imperial ruling class, etc. After every recession in the twenty-first century more and more jobs have been automated away. When I was sketching out the larger cycle in 2014, I imagined that it would be the combination of automation, neoliberal capitalism, and a lack of safety nets for the gutted middle class in the industrialized world that would bring on our version of the 1930s and 1940s. Silicon Valley “experts” were predicting that fifty percent of middle-class jobs would disappear across two decades — the ’20s and ’30s. “Unemployment” is loosely set in the 2030s. When I made those “Contagious Unemployment” sculptures, which are actually based on images of more familiar coronaviruses like the common cold — they were a metaphor. Now they’ve become disturbingly literal.

ED: Are you an advocate of Universal Basic Income (UBI)? I take those videos to be unironic, but I guess they could be read otherwise. UBI is a policy that appeals to a wildly diverse ideological spectrum, including tech bro libertarians as well as people on the left.

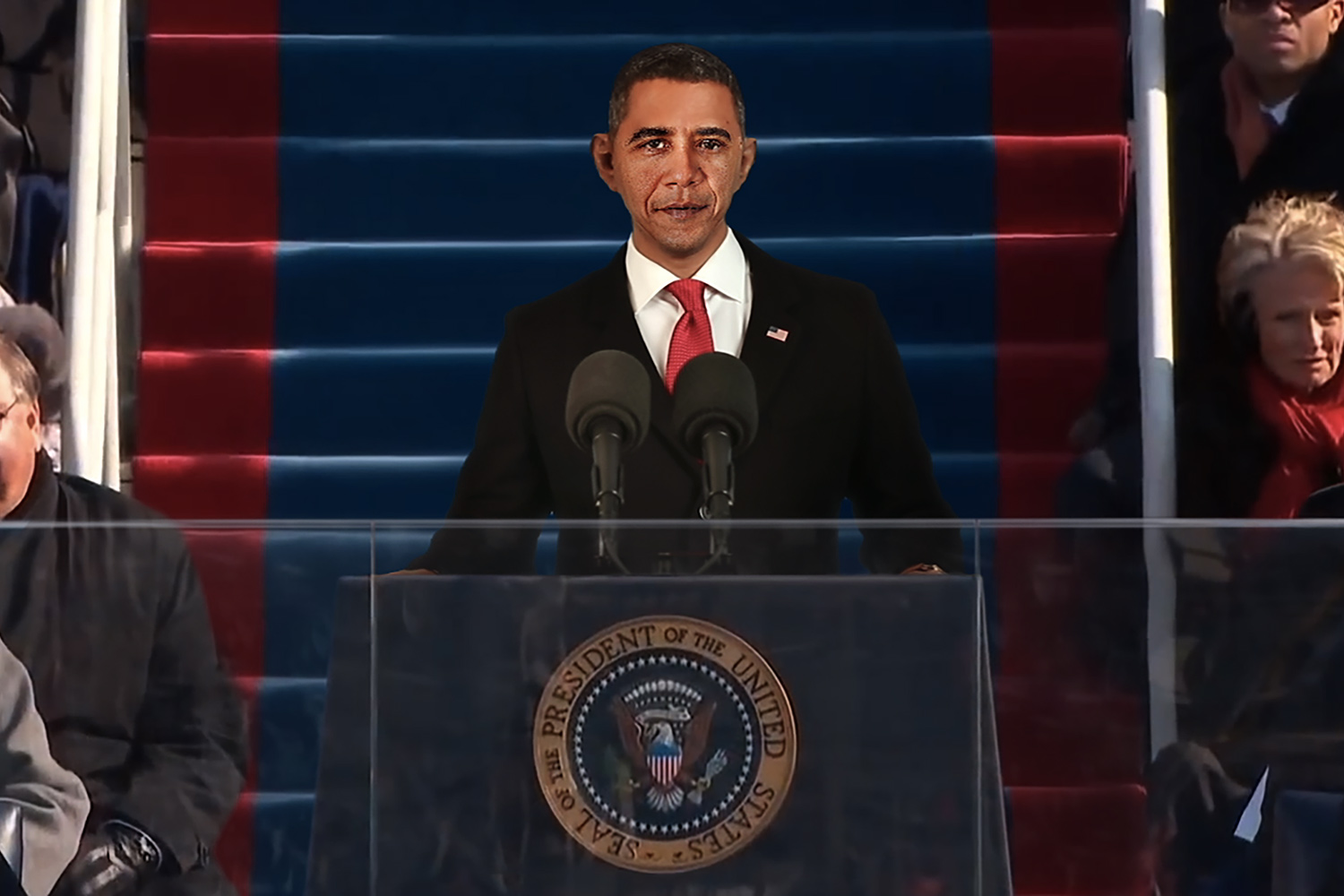

JK: Europeans often insist that Universal Early Retirement (2016), my video about UBI, must be ironic. Part of it is that the video is based on real American political commercials for Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton — and that European commercials are nothing like what you see in the States. This kind of political advertising is alien to Europeans. The other part is the casting. The video is set in 2032, during an American presidential election year — which at the time, I thought might be the earliest point that UBI could become a real political issue in America. 2032 is around a decade before America is predicted to finally become a majority minority country, and I cast the video accordingly. When I showed it in Turin, I was amazed how many people told me the video must be ironic because of how much it reminded them of a multicultural Ikea ad.

I believe in UBI. Our society is rich beyond imagining, but those resources are unequally and unjustly distributed, both within countries and on a global scale. With the advent of advanced automation, there’s no real reason for most people to do jobs they despise. A real living wage UBI is a both a safety net for people displaced by automation and a set of training wheels for a true post-work future. I believe in the inherent indignity of most forms of labor in capitalism. Using a human being to scan and bag groceries, dig coal, or file paperwork eight hours a day, five days a week, forty-three to fifty-two weeks a year is an obscenity. People are not machines. It sounds silly when you say the words “fully automated luxury communism,” but it’s actually a very serious human-rights project.

ED: Your work has generally taken as its subject matter that historical present I was talking about — you have often addressed, sometimes rather quickly and very directly, current events. Therefore, this pandemic and economic catastrophe affects you not just on a practical level or as an engaged citizen, as it would if you were, say, an abstract painter, but also on a thematic or conceptual level. So, how do you respond to this crisis as an artist?

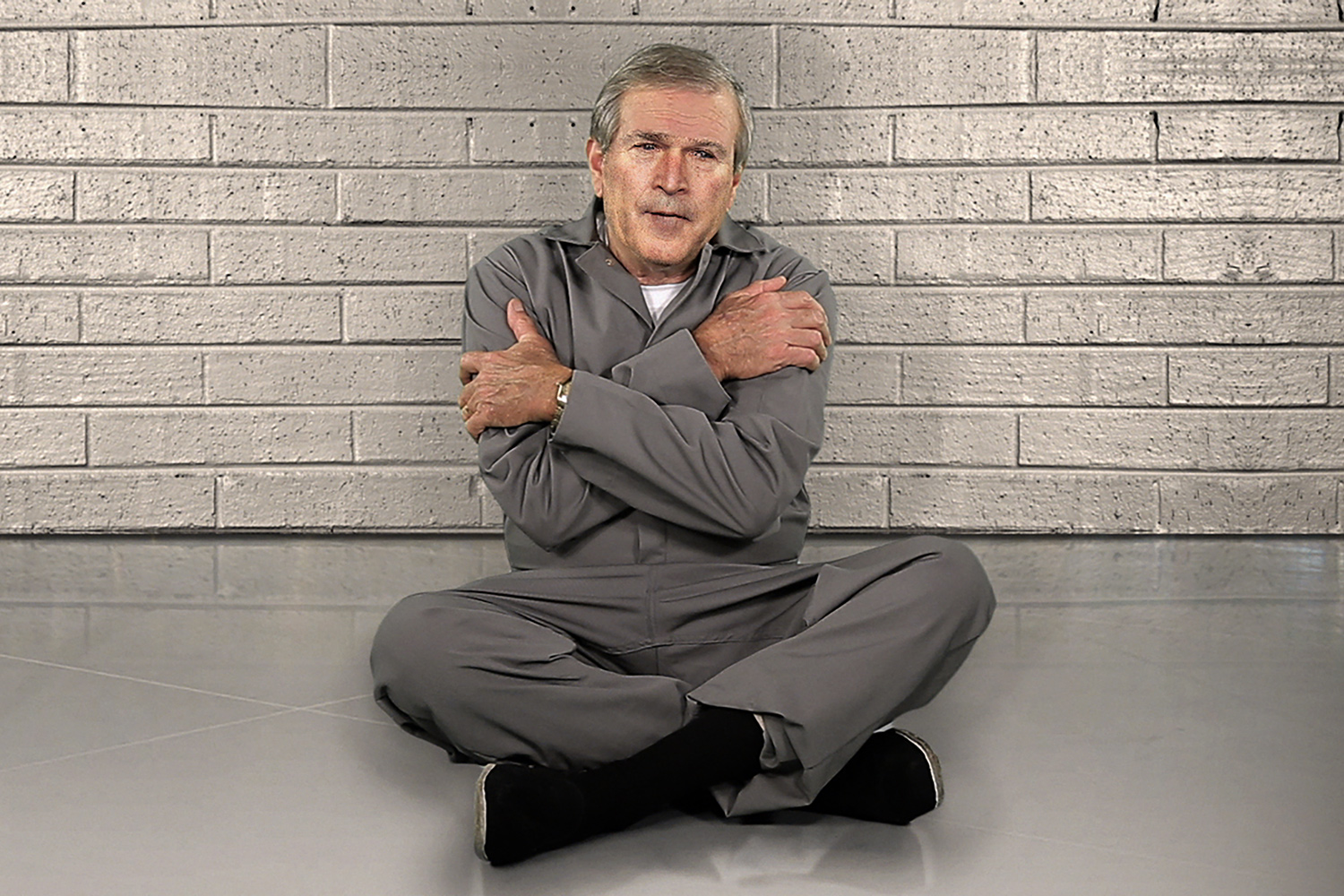

JK: At the height of the fad for European “post-internet” art in the early 2010s, when people were trying to pin that label on artists in New York, I used to joke that people should call me a post-9/11 artist or a post-Lehman Brothers artist. In the first week or two under lockdown I realized that my entire adult life in America has been lived in a time of escalating concatenated crises, beginning with George W. Bush’s election (I turned twenty-one in August 2000) and followed by 9/11, Bush’s ill-fated war on terror, his invasion and occupation of Afghanistan and Iraq, the financial crisis and ensuing “Great Recession,” Trump’s election and presidency, and now COVID-19 and its awesome repercussions. With increasingly frequent localized ecological calamities erupting in the background (or foreground depending on where you live). My art is about this larger crisis you see when you zoom out — about what Gibson calls “The Jackpot.”

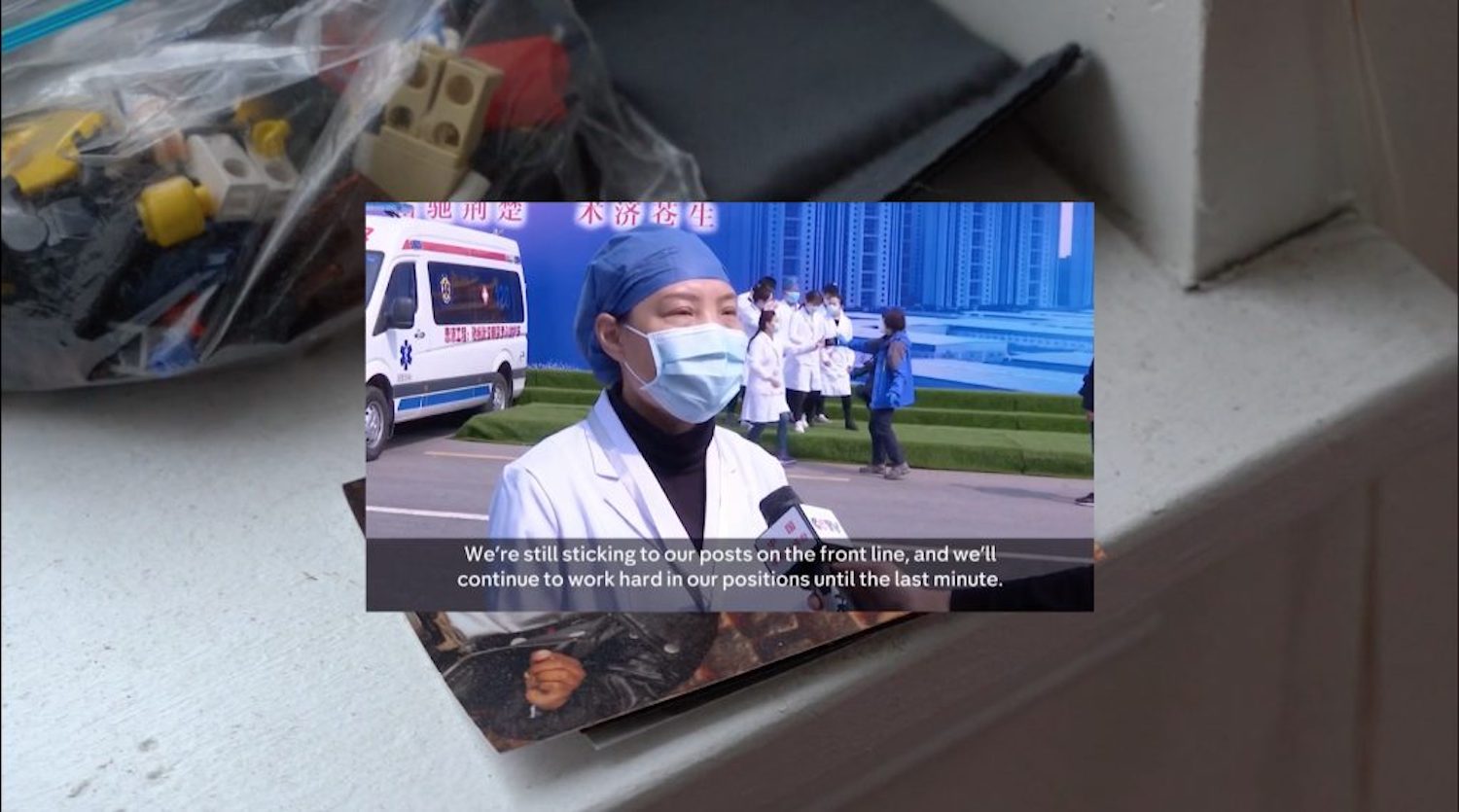

My work right now is about the future, but it’s also directly influenced by and about current events. This has been true of everything I’ve done since film school. The third chapter in my cycle, “Civil War,” is about the potential violent end of the American middle class, but it was also about Trump’s Republican Party. I’m at work on the second and third parts of “Climate Change,” the fourth chapter in my cycle. The first part was about American nationalism and white supremacy causing the American global order to melt down. Since the summer I’ve been in production on Part Three, a short 16mm film called Adaptation set in a flooded mid-twenty-first-century New York. I shot it in August and December, before the outbreak. It’s become a lot moodier and melancholy since then, as I edit it and work on the color and special effects during the pandemic. I feel an urgency around finishing all this work. I don’t think it’ll be possible to make the kind of art I do in a decade or two. The pandemic feels like a dry run for what’s ahead in the coming decades because of climate change. Trapped in my apartment for months, I’m not expecting to make any sculpture — or any media work in 2020 beyond this film that’s already in progress.

ED: At the same time, while the specifics of what’s happening are frighteningly novel, the conditions are very familiar, and many are precisely the themes that you’ve been examining in your work — inequality, precarity, contamination, etc.

JK: I totally agree. The impact of certain technologies — like social media, AI, and other kinds of automation — are novel, but the results of mass unemployment, extreme income inequality, and xenophobic nationalism are well known. They were studied for half a century after World War II. The whole Western postwar global economic order was designed to prevent another Great Depression and hopefully another world war. The neoliberals, Reagan, Gingrich, the Bushes, the Clintons, turned their backs on all of that knowledge.

ED: And then there’s the nationalism thing. I think that theme became really pronounced in your work in “Civil War,” and specifically in the film Another America is Possible (2017) with its optimistic vision of the future. That show opened in the shadow of the election of Trump; meanwhile the nationalist response to coronavirus has been vicious and predictable.

JK: Over the last two or three decades, the West has seen the return of the kind of nationalism that burns countries down. Before Trump was elected, I thought the US had a couple more decades left before real civil conflict could break out. Now I think we’re frighteningly close to the edge. With both Another America is Possible — which features a happy diverse family cookout in 2043 that ends with Confederate flags going into a bonfire — and the UBI video, I wanted to present the other option. You can have dystopia or you can work for a society where everyone has a real chance at happiness and well-being.

America’s problem is the same one it’s had since the beginning. There’s a sizable part of the White population that loses its mind over real racial equality. It’s only recently that I’ve understood what the contemporary American Republican Party is. The political descendants of the pre-civil rights Southern Democratic party — the heirs of the Dixiecrats — have taken over the Republican Party. Before civil rights, the American South was a one-party authoritarian state within a state. It’s long been known that the Democrats lost all these people when LBJ pushed through civil rights, but what has been poorly understood is the Dixiecrat response. They took over the Republican Party and now control the larger country. They want to remake the entire country in the image of the 1950s South. They want a one-party country with minority rule. All the major Republican figures in congress are from the South: Mitch McConnell, Lindsey Graham, Jeff Sessions, Ted Cruz, etc. The Republican Party isn’t a regular political party; they’re a revolutionary party. Even now, with COVID-19 ravaging America, all these people care about is their fucked-up agenda.

ED: You had a show, “Alternative Facts,” at Various Small Fires in Seoul, which consists of all these American flags, smooshed and wrinkled and folded and smeared with dirt and sealed in a kind of resin and affixed to the wall with flat-screen TV wall mounts. I did a virtual walkthrough of the show right as the US was shutting down and South Korea was reopening. It was a very strange experience. Obviously, the flag is a capacious symbol — sinister, to be sure, but multivalent — one reason, no doubt, that it has been incorporated into so many works of art. I have to say that seeing all those flag works on Zoom felt like the specific tenor had just shifted. What was it like for you opening that show under these conditions?

JK: It’s been a strange experience. It’s the first solo show I’ve ever made that I couldn’t install in person. I installed over Zoom in my second week in lockdown and got really depressed for a week afterwards. Somin, the director of the gallery in Seoul, took me for a walk via Zoom during install when she went to get a coffee. Seoul was opening up right as our lives were slamming shut in New York for who knows how long. They had the pandemic under control. Meanwhile, in the US, Trump is still trying to spin and propagandize his way out of a vast disaster. As a result, something like fifteen hundred people are dying a day here and hundreds of millions of people are either forced to stay home or to risk their lives going into work while our national government does nothing. The TV sculptures I’ve made are in many ways about Fox News, which enables and sustains this malignancy. I wake up every day and wish we could change the channel. I really hope Joe Biden or whomever the Democrats end up putting on the ballot in the presidential election can get their shit together and find the remote control.