The Kunsthalle Bern is empty again. All of the windows are open. The lights are out, and white walls and herringbone floors hold the glow of a late September sun. Park McArthur’s exhibition “Kunsthalle_guests Gaeste.Netz.5456” joins a history of empty exhibitions at the Kunsthalle Bern. In “Money at Kunsthalle Bern,” in 2001, Maria Eichhorn used her exhibition budget to pay for the building’s repair and in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou in 2009, “Voids, A Retrospective” recreated empty exhibitions from nine artists including Yves Klein and Bethan Huws. Like Eichhorn, McArthur also made one improvement to the building’s infrastructure: expanding its WiFi network (for which the exhibition is named) so it reaches the entire building and the surrounding outdoor areas.

These different modes of contemplating or confronting emptiness, as well as a lineage of institutional critique, are present in McArthur’s work. But it is the question of presence itself that is paramount. In preparation for this exhibition, like many pandemic-era shows, the artist was not present. Instead, McArthur spoke to Kunsthalle employees and other artists familiar with the building in order to create a description of each room in the space with orienting details like, “To the left of the Entrance Hall is the building’s staircase and a long narrow gallery with three windows called Aaresaal. The Aaresaal is named for the Aare River, which its windows overlook”; precise observations like, “The elevator is a type of lift known in German as Niederfluraufzug, low floor elevator. It locks into place with a low boom”; and a long list of all the stops busses and trams make after passing the Helvetiaplatz stop outside the Kunsthalle. An employee of the Kunsthalle recorded McArthur’s transcript in a softly Swiss-accented German and English, which can be played from the Kunsthalle’s website while walking through the space or from anywhere. Walking from hall to hall, a direction or detail calls back a drifting attention. This is a meditative experience: noticing thoughts, returning to presence.

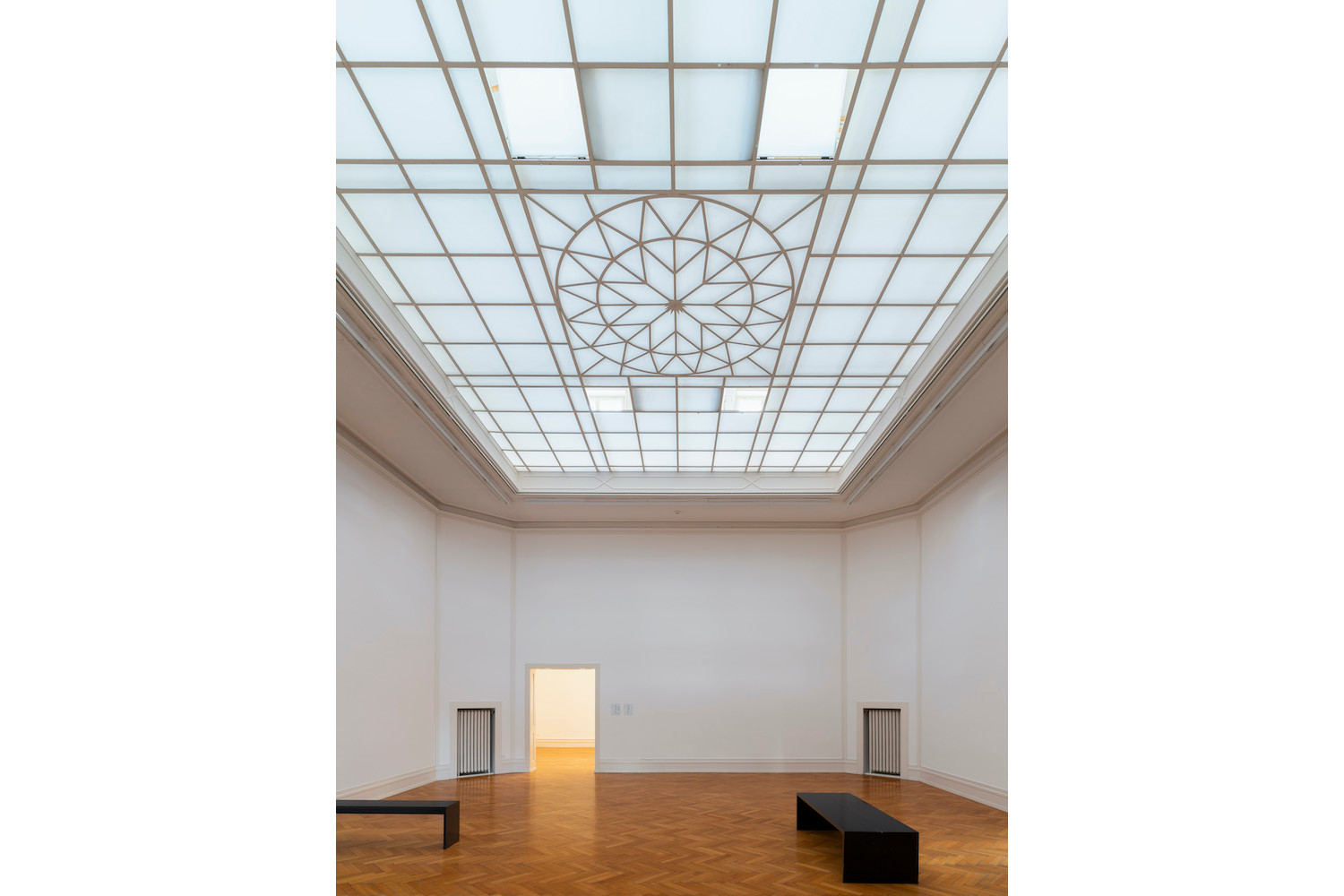

Being physically present in an exhibition space is a question of access. Taking her own experience of physical disability as a starting point, McArthur’s practice addresses how the institution constructs normativity and ability/disability, often misunderstanding accommodation as access. In “Kunsthalle_guests Gaeste.Netz.5456” a subtle play with the division between inside and outside alludes to questions of who spaces are (not) built for, and how that is physically inscribed. Opening the building’s windows is an attempt to draw attention to these boundaries: a gesture easily mistaken for compliance with recommendations to limit the spread of COVID-19, were it not for the audio’s emphasis on the degree to which they open, the quality of their translucence. She also moved two bas-relief lion head sculptures from the exterior walls of the Kunsthalle to the inside. They hang low on the wall, mirroring the placement of their counterparts outside, as well as what would be eye level for McArthur from the vantage point of her wheelchair. Like the benches used for past exhibitions, which McArthur clustered in the main hall and throughout the exhibition, these repositioned lions also recall Michael Asher’s 1992 exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bern, in which he moved all the building’s radiators into the foyer of the building. As both artists unearth the institution’s infrastructure, McArthur’s intervention subtly inserts her own subjectivity, while Asher guts the institution to posture opaque metaphors about power and the systems that centralize it. In McArthur’s Form found figuring it out (2020) — eight pairs of prints pasted directly to the wall, each a copy of text and markings as they would appear from the inside of the incentive spirometer respiratory device that McArthur uses on a regular basis — her body emerges again as a kind of specter from this inside/outside conversation.

What are the stakes of presenting oral and written recordings of a space amid a flurry of online viewing rooms and VR scans? Can this exhibition cut through the muddle of what the function of an exhibition is in a moment of evolving restrictions and continuous uncertainty — or at least function as a pause? Or has the widespread, pandemic-prompted reflection on presence and access muddled this exhibition’s ability to make much of a claim? Is it significant that McArthur, whose own embodiment of physical disability expands the paradigm through which she envisions access, poses these questions? “Kunsthalle_guests Gaeste.Netz.5456” doesn’t answer these questions, and in that way leaves the visitor, in Bern and online, wanting more. But it does raise them and offer up a space with good WiFi to mull them over (or not.)