One could easily miss Henrik Håkansson’s installation A Tree Mirrored (Pinus Cembra) (2020), camouflaged as it is amid the surrounding greenery at the bottom of Vallunga in the Dolomites. On closer inspection, the silvery needles of the freshly planted tree, with a polished metal plate at its base, appear a different shade of green than that of the native pines lining the valley. The square reflective base that takes in the sky and puts the rose-colored jagged mountain peaks at one’s feet reminded me of the mirrors placed beneath soaring cathedral vaults so that visitors can inspect their finer detail. The awe-inspiring “pale mountains,” with bulbous shapes as if carved by stonemasons, invite all sorts of comparisons. Le Corbusier himself called the Dolomites “the most beautiful architectonic work in the world.”

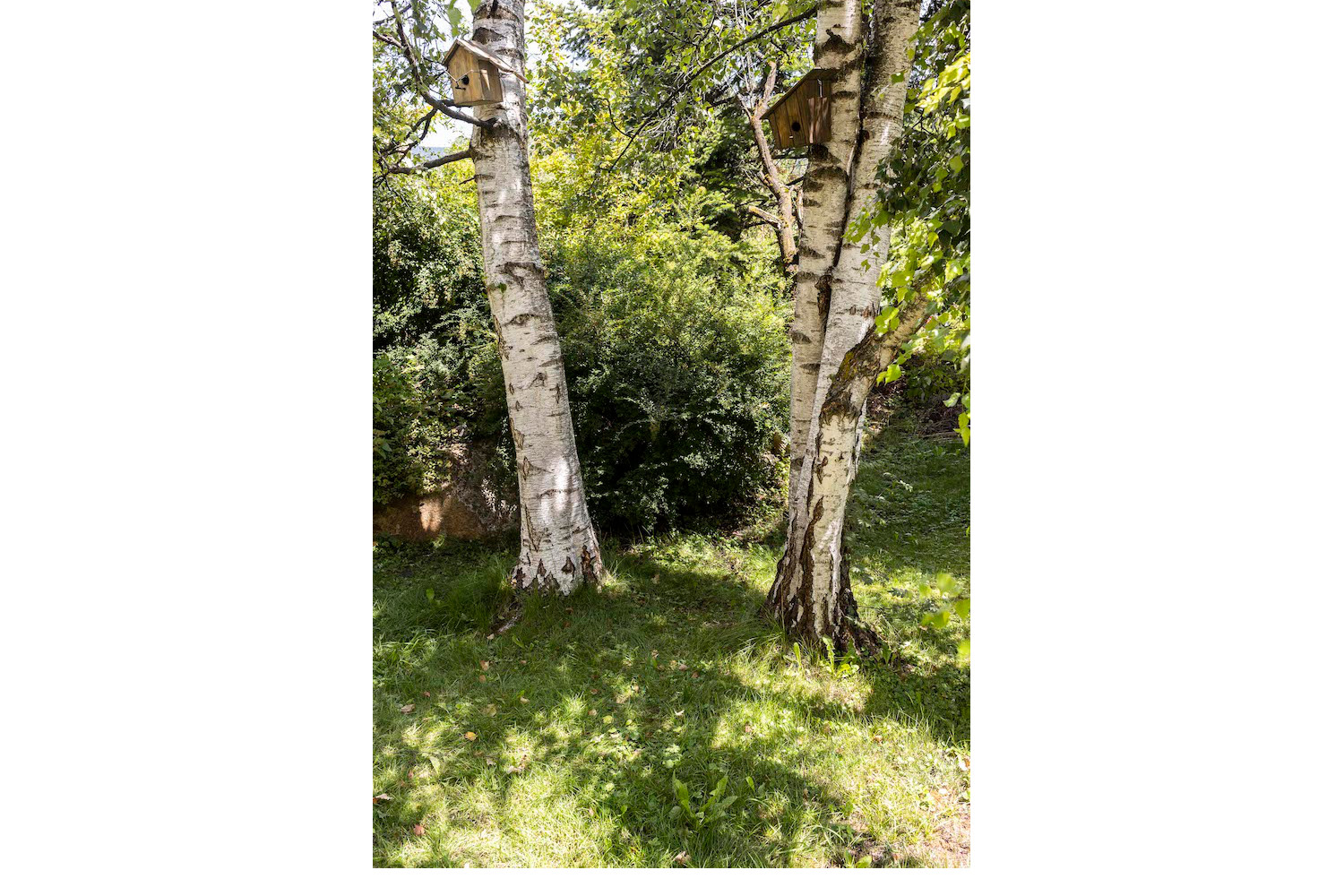

Artist Marcello Maloberti sees mountains as “the teeth of God” in his series Martellate. These terse, often poetic statements, written out in distinctive black capital letters against a white background, appeared in Italian, German, English, and Ladin — the vernacular language spoken in Val Gardena and the neighboring valleys — on cloth bags, banners, and posters that visitors were welcome to take away. Dotted around the villages of Ortisei and Sëlva, they were an integral part of the visual identity of a biennial that prides itself on being text- and language-based. If the event had an audio identity, it came in the form of Petrit Halilaj and his partner Alvaro Urbano’s sound piece installed at various locations across Ortisei. When first encountering the work, passersby were arrested by familiar snoring sounds — produced and recorded by each of the artists in turn — seemingly emanating from birdhouses hidden in tree crowns. But the discordant effect and the joke wore thin after a while, and one such installation would have been plenty.

Now in its seventh edition, the Gherdëina Biennale started out in 2008 as a collateral event of Manifesta 7, which took place in South Tyrol that year. Its founder and director Doris Ghetta runs an eponymous gallery representing local sculptors such as Aron Demetz, and Bolzano-born Ingrid Hora, all of whom have works in this year’s edition. For the third time in a row, the Gherdëina Biennale was curated by Prague-based Adam Budak, who had been part of the curatorial team of Manifesta 7. Addressing members of the press at the Hotel Adler in Ortisei, he admitted that staging this edition amounted to a “gigantic challenge” owing to budget cuts and months of work lost because of the lockdown in what was among Europe’s worst-hit regions in the early days of the pandemic.

But the event had the backing of Ortisei’s enlightened mayor and editor of the informative cultural guide The Ladins of the Dolomites (2016), Tobia Moroder, whom Budak presented with a rough-hewn Tree of Knowledge, a limited edition art work by Myfany MacLeod

— a nod to the woodcarving tradition Val Gardena is renowned for. The gift’s biblical theme resonated with Canadian artist Myfanwy McLeod’s outdoor sculpture Fallen (2020), inspired by a statuette found at Ortisei’s Museum Gherdëina. Painted a pale peppermint green, these giant (and rather ungainly) wooden effigies of Adam and Eve, with colorful apples strewn before them, had the merit of matching the pretty Tyrolese townhouses at the upper end of the village’s main street where they were strategically positioned.

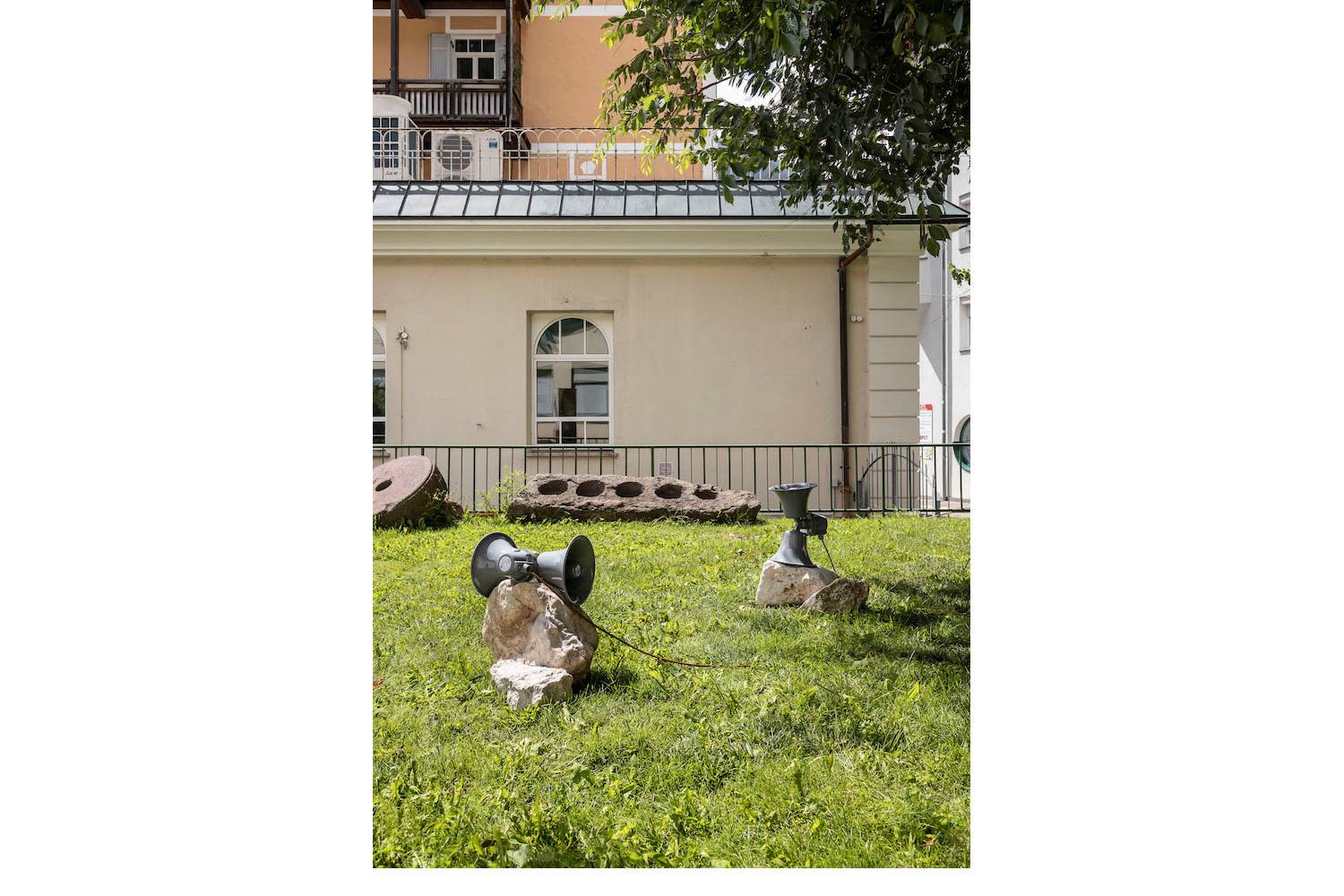

The Gherdëina Biennale emphasizes artworks in public spaces that can be encountered by everyone, not just contemporary art aficionados. In the run up to the opening weekend, the streets and squares of Ortisei were subtly — and not so subtly — transformed by artistic interventions, including Czech artist Habima Fuch’s mural Comprising the Universe (Five Elements) (2020), drawing on Tibetan symbolism, and Pavel Büchler’s appropriation of the neon sign above the dilapidated Hotel Ladinia as well as his sound sculpture Dialogo (2013), referencing Galileo Galilei’s famous work projected via loud speakers in Morse code. Located just off the main square, Maria Papadimitriou’s walk-in installation Disco for One (2020) is an homage to the legendary music producer Giorgio Moroder — known as the “father of disco” — who hailed from Ortisei. Its title notwithstanding, I saw more than one kid at a time dancing around inside the diminutive Alpine hut framed by trees.

The bulk of the biennial was spread over two exhibition venues, visually connected by Swiss artist duo Lang/Baumann’s eye-catching twin Beautiful Steps #17 and Beautiful Entrance #8 (both 2020), painted in bold vertical strips on the staircase located beside the entrance to Sala Trenker, crammed full of artworks (so much so that Budak himself likened the experience of visiting the space to “walking through a very dense forest”), and along the facade of the atmospheric Hotel Ladinia, housing a retrospective of shorts by experimental Austrian filmmaker Josef Dabernig, among other offerings. When I bumped into the artist at the latter space shortly before it officially opened to the public, he offered to take me to a nearby dental clinic — surely the most unlikely of biennial venues — to view his Heavy Metal Detox (2019), containing graphic images of the artist’s own teeth filmed as his metal fillings were being replaced.

The Gherdëina Biennale makes the most of its stunning natural setting. Walking in the hills around the valley one can stumble upon remnants from past editions. That evening, some of us braved the steep ascent up to Teatro Pilat, the site ofartist Gregor Prugger’s farm and atelier, which boast spectacular views of the Sassopiatto massif. In the barn beneath the artist’s studio, where a feature-length film by Sharon Lockhart was being projected, Paulina Ołowska was busy applying makeup and putting the finishing touches on costumes and headdresses based on a set of 1917 drawings by her muse, the Polish artist Zofia Stryjeńska, ahead of the Slavic Goddesses and the Ushers performance/tableau vivant that was among this edition’s undisputed highlights. Meanwhile, artist Antje Majewski and her collaborators, the barefooted Agnieszka Brzeżanska and Prugger, were presenting and doing a spot of fundraising for the path Alexander Langer, destroyed by a storm, that leads from Pilat, through the Sanctuary to the cascades.