The ellipsis suggests dilation, a space for curtailed retrospection or future elaboration, a surfeit of meaning to be uttered or a disintegration of speech altogether. Siding with elision as potential, the medium specificity of “painting” in Marc Camille Chaimowicz’s exhibition at Cabinet Gallery evaporates into an embodied, consummate éclat. Here, Chaimowicz has reconfigured a scale model of his apartment, echoing an earlier iteration, One to One… (2018), exhibited at Kestner Gesellschaft in Hanover. Since the experimental home-studio of Approach Road (1974–79), Chaimowicz’s private interior space has become material to test the domestic as pseudo-biographic; staged, synthetic, synaesthetic; a mellow blowout on the friction of inhabitation and identity; a disorganization of the interior/exterior divide.

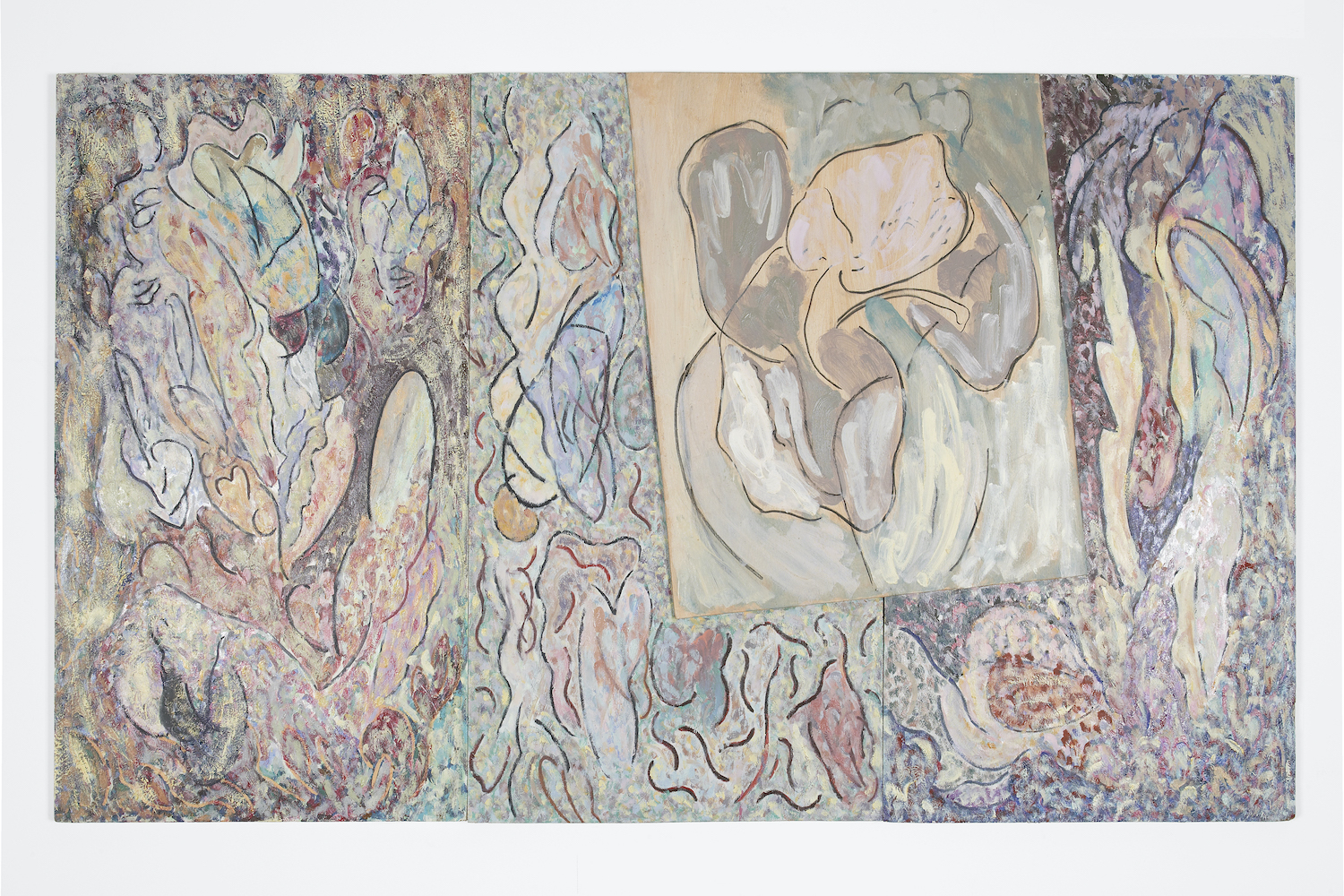

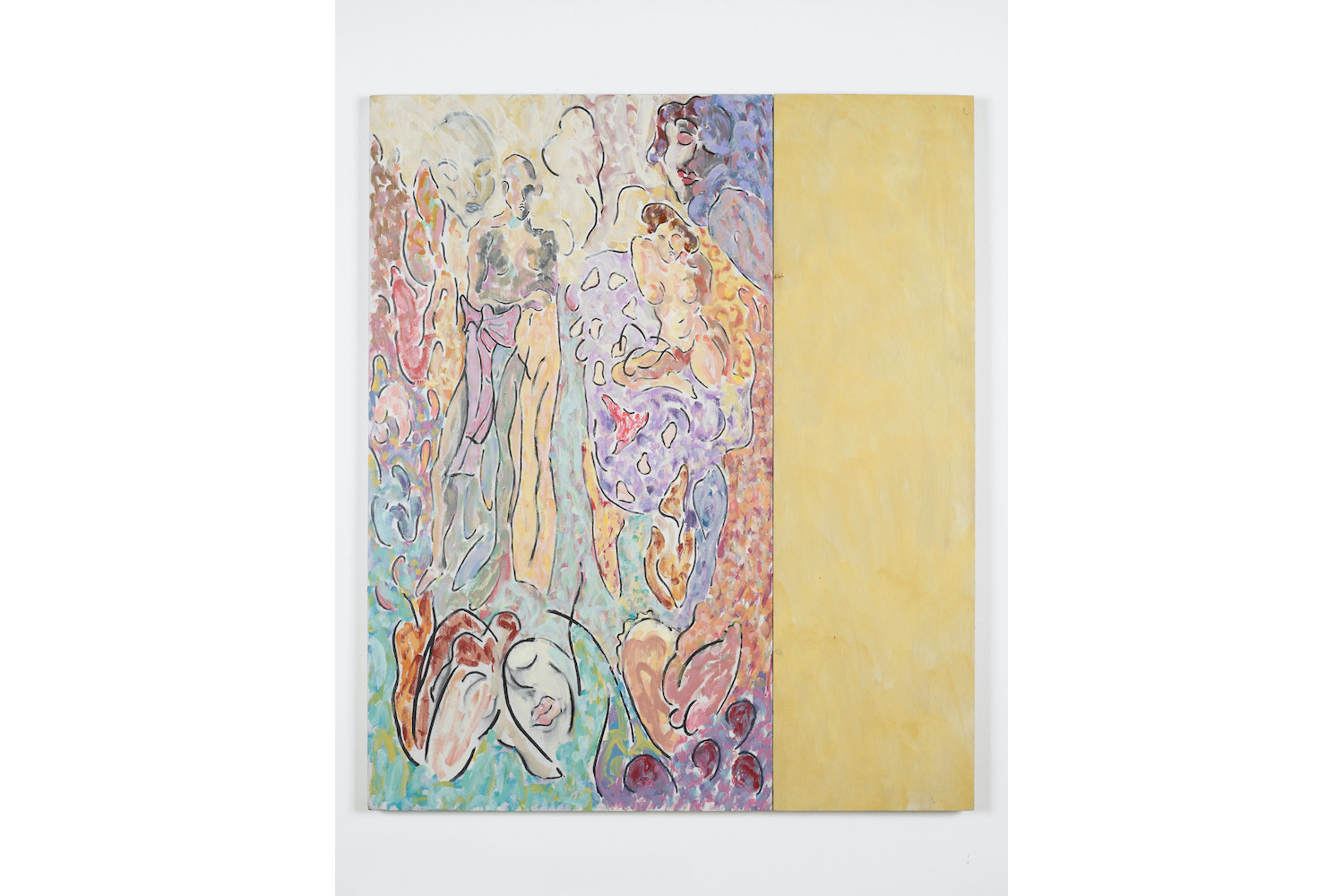

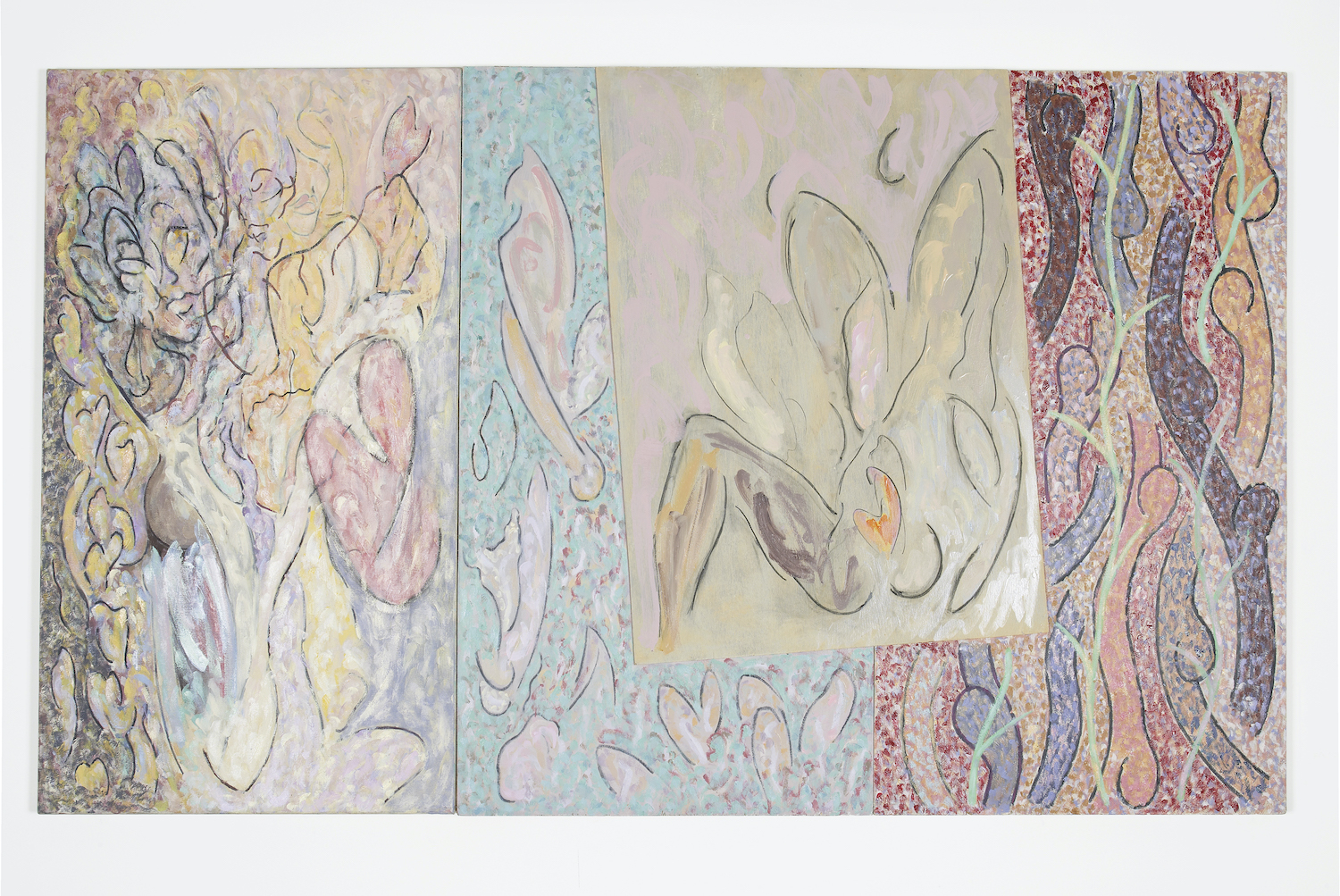

Spatiality is in a state of deshabille, effectual and atmospheric like a chiffon veil. Objects line formal pathways or function as burlesque winks at peek-a-boo axes. This disheveled beauty is non-diaristic yet abundantly personal in its relation between subject and space: incorporating works from multiple decades, the environment is strewn with shifting temporalities. Five fragmentary partition walls designate soft clustering space with interlude-hues of lavender, pale peach, and dove gray. The choreography of these parenthetical walls divert eyelines to, or host themselves, layered dialogic surface play: lemony Vuillard flurries, figural fuzzings, lashes of Bonnardian curls dappling existing boundaries; a strip light of throbbing New Romantic blush radiates its randy aura; mirrored panel-doors hang with a diamond-cut center while filigreed wallpapers and boards befit the total-pictorial.

In displacement comes fantasizing, and Chaimowicz enfolds his poetics and charm into the fabrication of space, offering a new positioning of the interior — a space where subjectivity permeates each object, where elements exchange postmodernist irony for pastel idiosyncrasy, where every corner, drapery, and piece of furniture elaborates on the courses of memory. In each reorientation of space, Chaimowicz embraces utility and phenomenology, feathered in time by mood and reminiscence. In this way, one might locate an air of loss in each successive revision; without an indicator of the inhabitant one is left to read the objects as an inventory of identification and performance as well as paradoxical symbols of transience. The only other disembodied voice on view is Andy Warhol, seen in a punnet of bananas, a set of Campbell’s soup cans, or more sterile in a violet print of Electric Chair (1971). Their comparison as artists suits for their pragmatism, cool erotics, and their figuring of artistic practice as expanded methodology, a manner of living. But the comparison also shadows an undertone that a subject always remains beneath the surface, however machinic or melancholic, however restorative or refined: “The canvas is covered in canvases, veils pile up and veil only other veils, the leaves in the foliage overlap each other.”1 In this balmy veiling, Chaimowicz’s phenomenological reorienting will indeed disperse beyond the canvas, frame, and the imaginary private space…