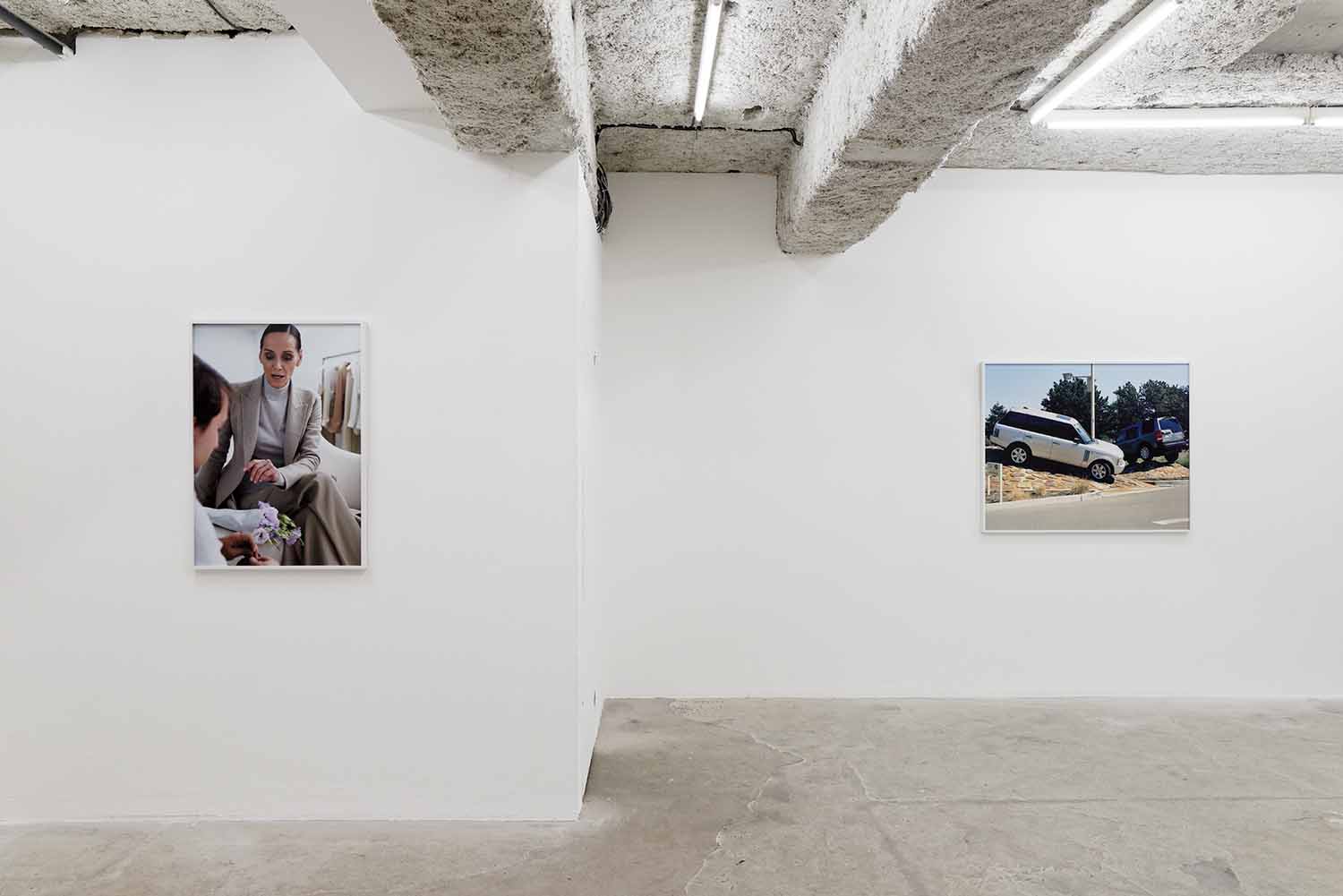

Draped in pink light, a young woman sits on a flower-patterned bed. Lorrie in Her Bedroom, L’Étang, Réunion (all works 2019), located near the entrance to “La Kaz,” a photography exhibition on view at Balice Hertling’s Belleville space, greets the visitor with a melancholic yet disdainful attitude. The viewer’s gaze almost feels displaced by this subdued genre scene that evokes a recurring moment in anyone’s life: coming home and reflecting on the day’s passage. This intimate take on documentary photography became photographer Fabien Vilrus and fashion designer Nicolas Guichard’s methodology for capturing life on Reunion Island. Helped by curator Juan Corrales, the duo photographed an often-ignored French territory, representing rarely heard local voices through imagery that is even rarer in the contemporary art landscape.

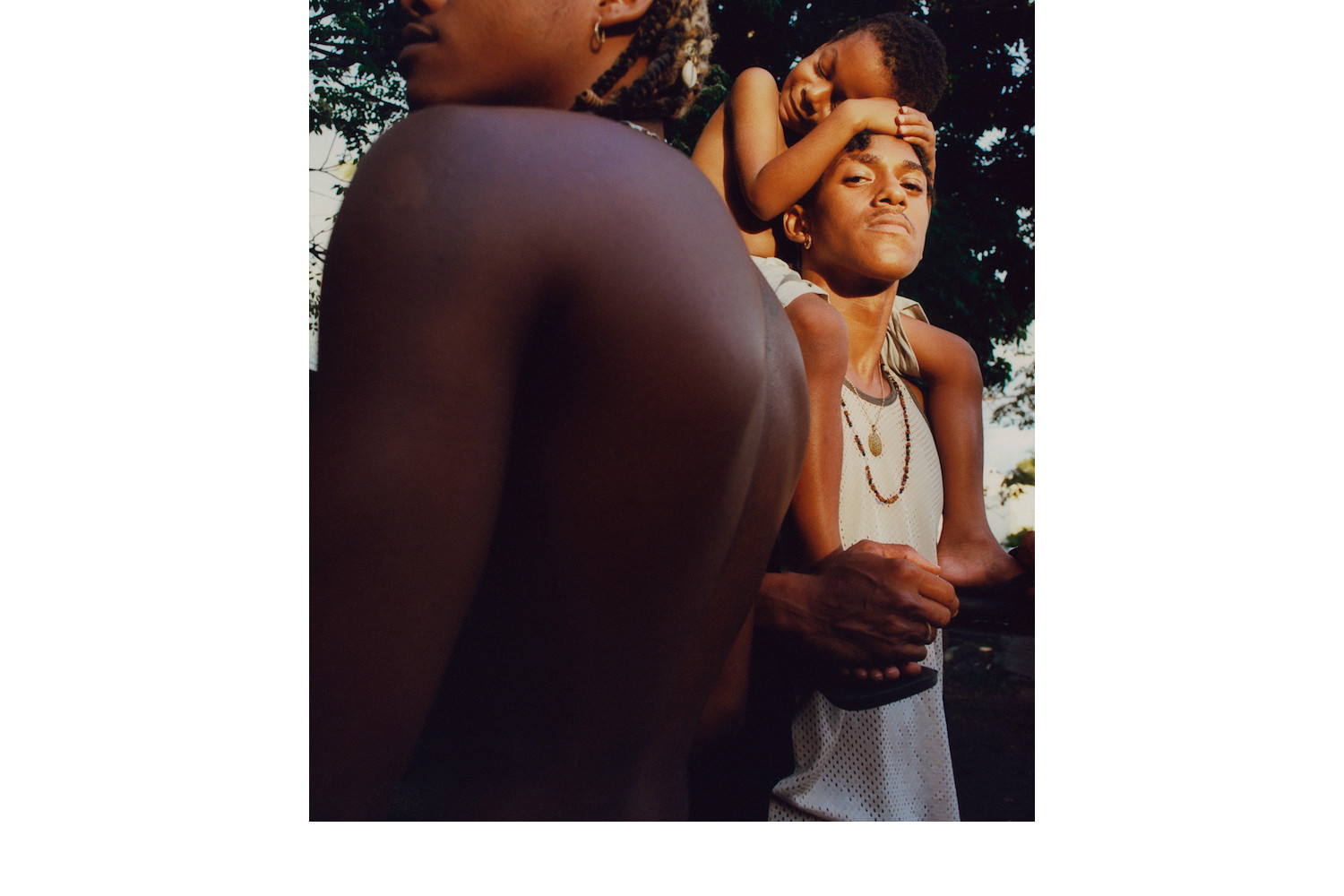

Hence the decision to shoot young people they did not know, favoring a neutral point of view. They came into their lives like discreet guests, as in Father and Son, Saint Paul, Réunion, in which the camera finds itself in a random yet remarkably choreographed living room. Indeed, every photograph has been framed to make the visitor believe in a conveniently photogenic reality, as hinted at by the color-coordinated flower bouquet in the corner. If the photographer has tried only to document what he saw, his mannered process reveals the inherent beauty of the inhabitants, or rather their dignity, their right to representation, and the beneficence of an aesthetic existence. The framing also showcases the sinuosity and muted colors of the traditional houses that gave their name to the exhibition and which form the mirror image of the portrait series. For these structures seem to already belong to the past, conveying an atmosphere endangered by globalization and architectural homogenization1 — an uneasiness almost hiding behind the images.

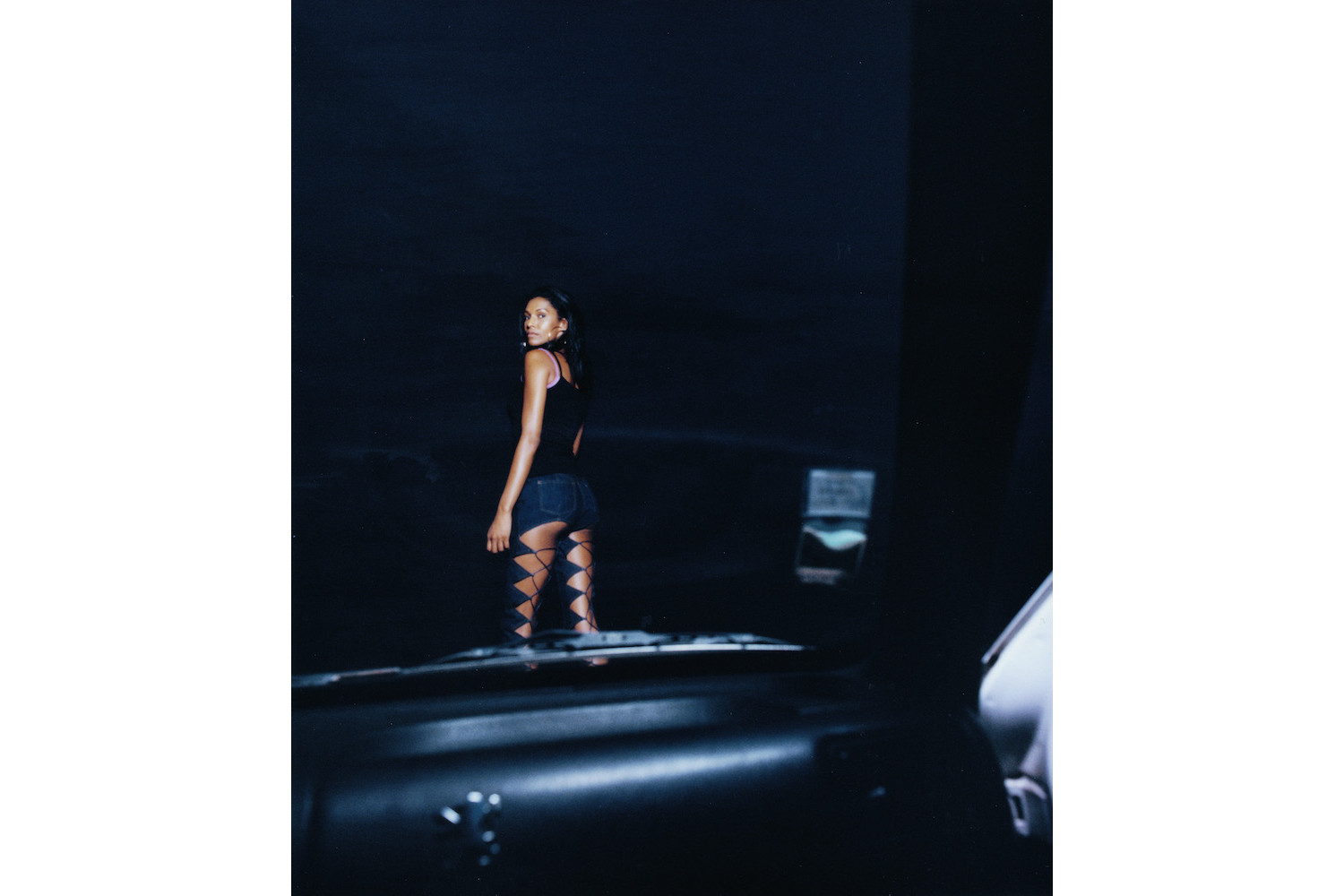

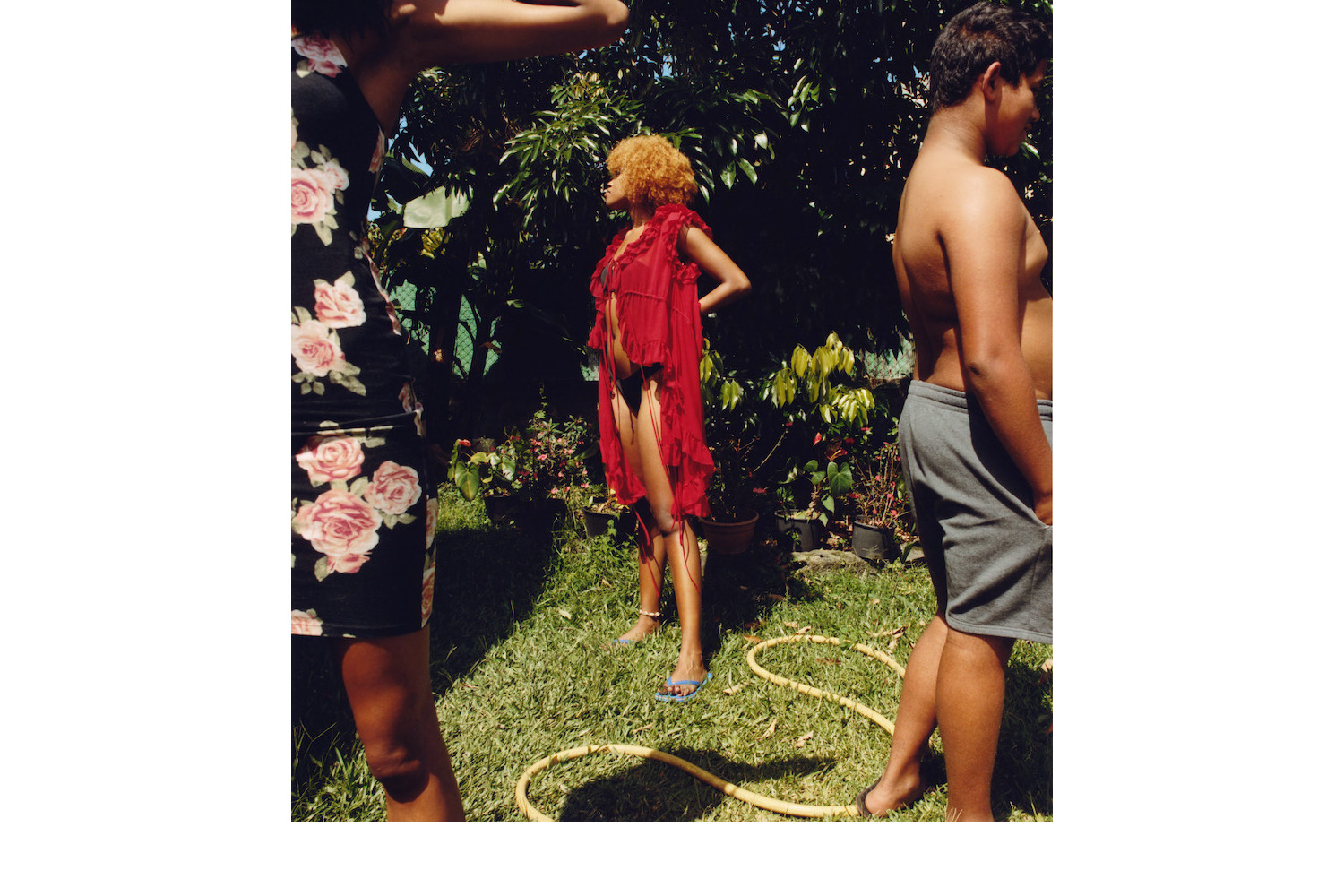

Contextualizing Nicolas Guichard’s first collection in an everyday setting, the artists play with the ambiguity of photography, the gray area between pure document and staged image. They also formulate an aesthetic that flirts with the uncanny.2 Ornella, Front de Mer Saint Paul, Réunion portrays an apparitional woman skillfully double-framed by the car’s window, as if the photographer stopped on the side of a deserted road to go to the beach in the middle of the night. The same woman appears in Before the Dancehall Party and, following the feeling of displacement evoked before, the pair of images exhale an odd ambiance due to their oneiric aspect. Displacement then expresses a mode of what appears other or never-before-seen. The subjects of the photographs, and their strength, also evoke the free-floating feeling of fearful interaction that defines much of contemporary life. As a setting for the uncanny, displacement — of the subject and the viewer — is therefore a way to express singularity and legitimacy in the framing of an image, investing it with an almost holy presence.

Reunion Island has often been trapped in representations deeply rooted in colonialism, exoticism, tourism, or a kind of fetishistic social realism.3 Here, the artists share a vision of an island they know, allowing its inhabitants an alternative to the tropes they have suffered from and at the same time making a statement: that the aesthetic is indeed political.