While gender stereotypes, particularly masculinity, are lately being called into question, the young photographer Buck Ellison explores advertising’s gift for peddling a conservative portrait of family life in which subjects are white, rich, straight, healthy, and always displaying the smile to which they feel entitled. Ellison’s second show at the Parisian gallery Balice Hertling, “Useful Life,” which includes a series of recent photographs and a video tryptic, raises questions about our current conception of the paternal figure. Born in California, the artist takes the viewer into an idealized world with the American dream as a backdrop: hard work, success, flashy cars, and the LA sunset.

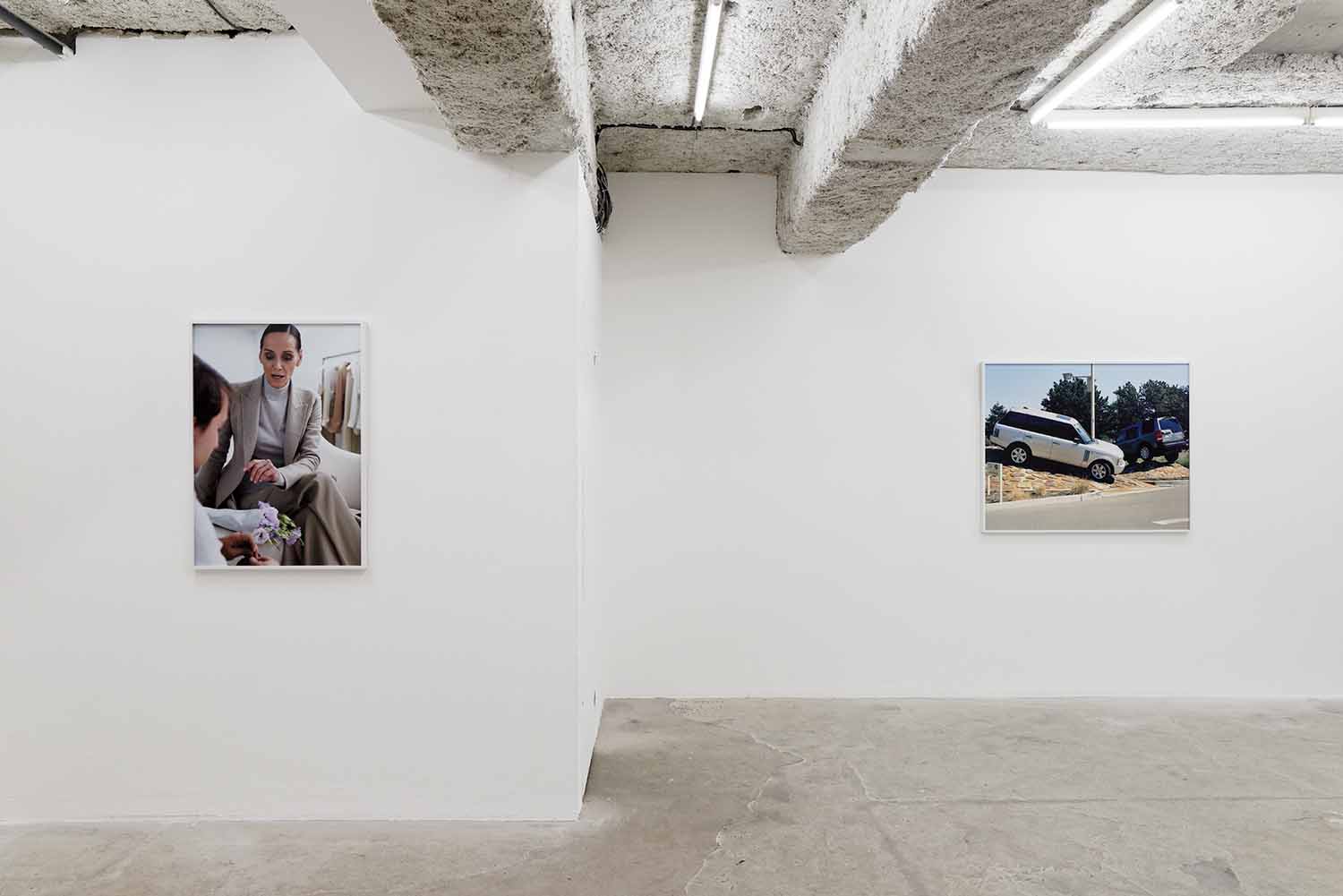

In graduate school Ellison used to look at ads in bank catalogues, often noting the repetitive nature of featured scenes: watches and perfume, golf and tennis. Equally disgusted and attracted to these visual representations of a certain culture of power, he started to produce his own pictures following the same commercial model: large format and briskly edited to promote consumer desire. Christmas Card #8 (2017) and Christmas Card #33 (2017) are part of a series inspired by his own family. Each member is an actor that has been cast. Clothes and accessories have been meticulously chosen in order to reflect a luxury lifestyle. If the result is striking, it is because the devil hides in the details, and the artist understands that. For instance, the characters’ body language, especially hand placement, is inspired by nineteenth-century paintings of families, in which both accessories and layout act as status symbols. Here they evoke cooperation and proximity, as well as the confidence of well-born people. Ellison plays with the habitus as defined by Bourdieu, depicting tastes, habits, and behaviors of a certain social class. He highlights the informal learning that has conditioned specific attitudes. Always positioned in the background of these portraits is the child — the artist incarnate — who recuses himself as if refusing the staged effort.

In a time when there are more blended families than nuclear ones — especially in the United States — and where same-sex marriage has been legalized in the whole country since 2015, Ellison points out the gap between reality and these simulacrum projections of happiness. Henry, Henry, Henry (2019), the major work in the show, is Ellison’s first film. Divided into three parts, a scenario is replayed with small variations each time, provoking a disruptive sense of déjà vu. Actors look slightly different; their outfits switch between a long-sleeve shirt and a Ralph Lauren polo. And here, too, the length, structure, and even cheerful musical theme can be compared to that of a commercial. The progression of an idealized day sets a narrative in which a father interacts with his son, teaching him violin, playing baseball with him, and even smoking a joint, living up to the cool dad archetype. In the background of these stereotypical images, we can read watermarks on how to prepare a boy to live with a sophisticated education and values such as leadership or competitive spirit. The construction of the film, which suggests that the other parent is behind the camera, gives way to more diversity; but we don’t know whether it is a second dad or a mother, since he or she remains hidden.

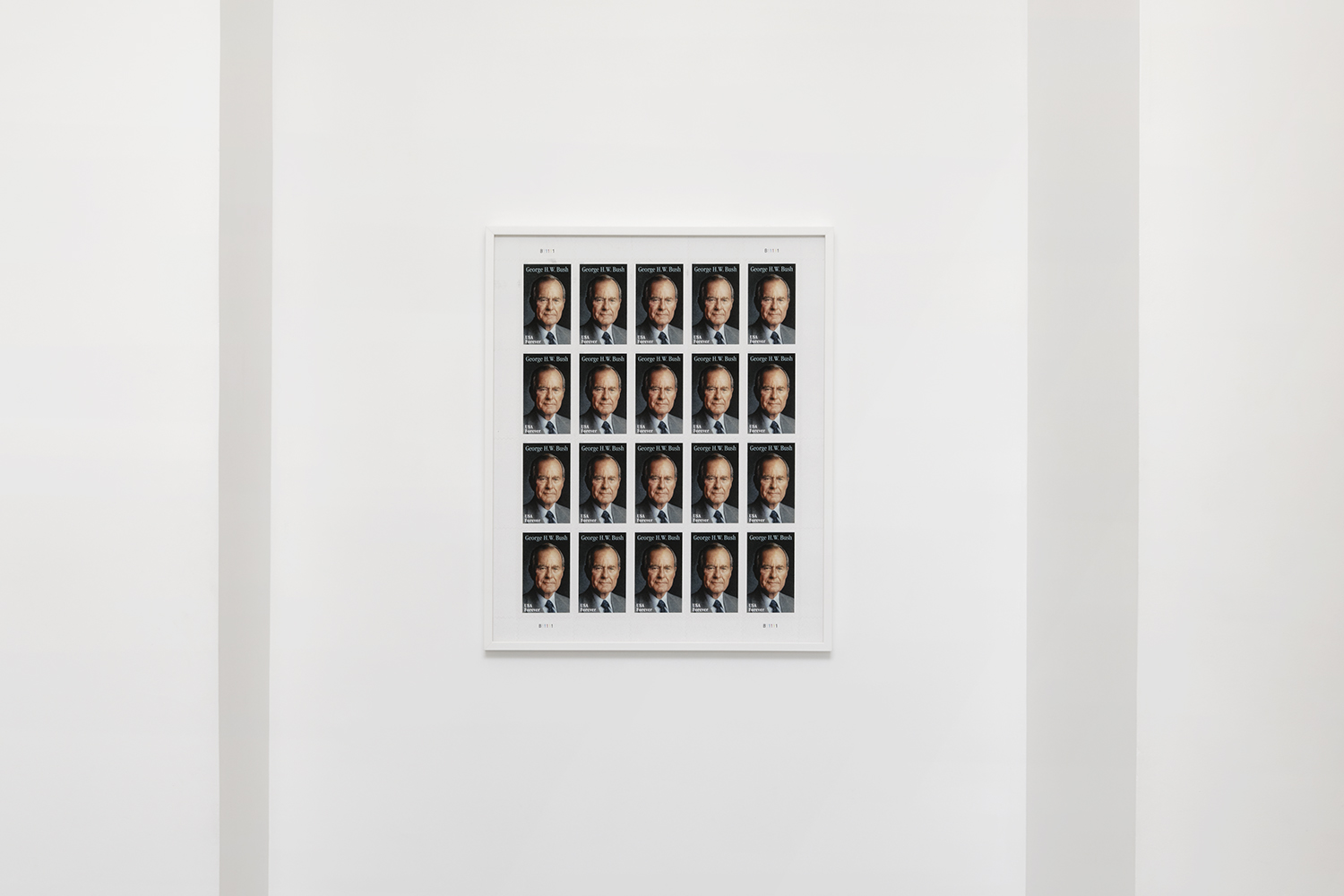

Similarly subversive is Stamps (2019), a rescaled scan of a sheet of George H. W. Bush commemorative stamps, which were recently issued after his death. By isolating and enlarging this small piece of paper depicting the nation’s previous patriarch — but also the parent of George W. Bush — Ellison points out the reach of this political tool and raises questions about descendancy and power transmission. Another photograph, Erik with Kitty, Blackwater Training Center, Moyock, North Carolina, 1998 (2019), shows a soldier in uniform. Erik is a neoconservative defense contractor who created a private army during the Iraq War and used to work for Bush senior. Thus, Ellison chooses to display a masculinity embodied through domination and authority — a representation that transpires in political discourse as much as in the hundreds of commercial images that are seen every day. By incorporating images of kittens and flowers, he subverts with sweetness — and perhaps a touch of humor — a gendered societal model built on collective projections.