Dear Amy,

I saw “The Shape of Shape” a few months ago now but it feels recent in that way that all good shows feel recent (garlicky lovers, smell sticks around). You’ve made a wonderful grouping of something and I have been returning to them in my mind, over and over, shifting together, another fold or angle or a line as though the works are sliding through topics of their shared conversation but in that muddy goop of memory distracted by the sensation of remembering toilet paper or buying eggs. The show felt like tripping into a crowd of friends having a long conversation about light, line and all the rest of it: shape. Porous is the shape as a boundary, as the membrane of the din of my first moments of viewing I went straight to Arp, stomach forward, the way that the body fits two hands cupped in the shape of a c while the rest remains lumbering in the middle of those hands, all of this felt somehow comforting, a wobble of several c’s all dog hair white marble (seas) resting against one another.

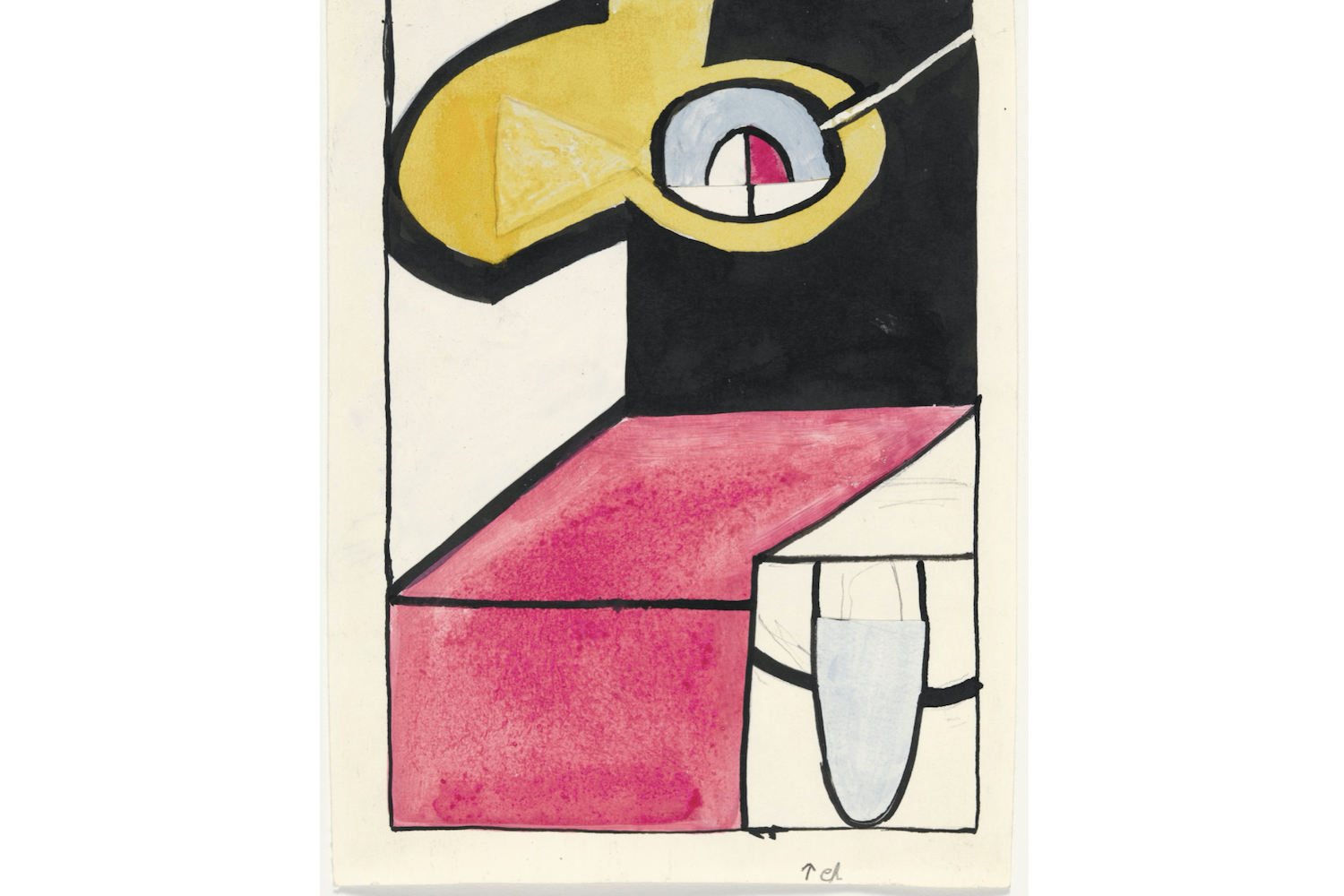

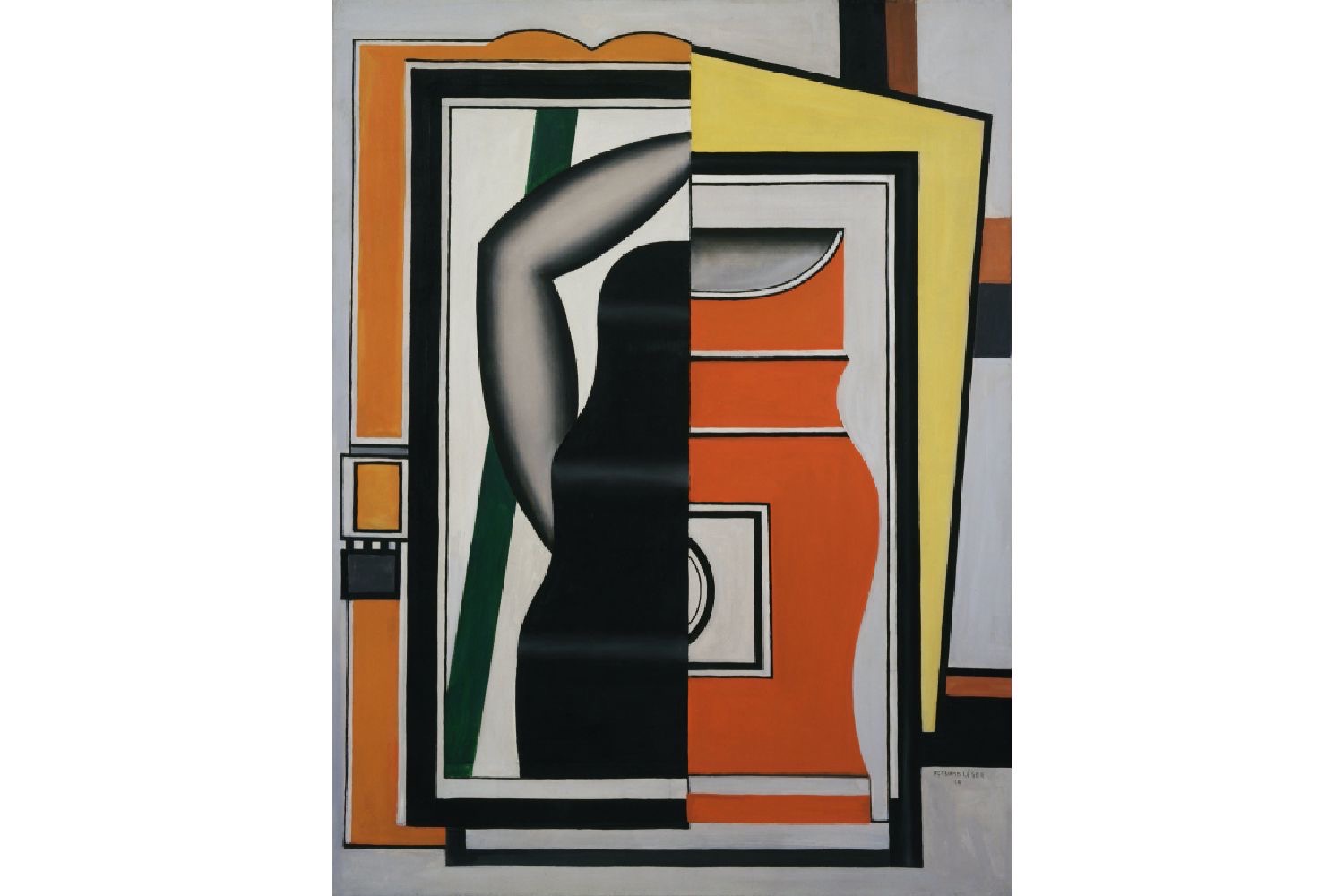

Pulling myself out of Arp’s dog hair, I start to read the crowd right to left, I listen that way too and so it begins. First to my eye is Jennie C Jones’ Five Point One Surround Portfolio of five aquatints (2014) in a score, a long top line positioned with Frankenthaler almost out the door, composure, disclosure, then a big burst, control and then composed again but reoriented. Then the Léger and the Laurens, likely spouting something off about space as negative and positive. The orange, the center or the outline? Or wait what is the Darie doing in the Legers? What is that yellow triangle inverting and how do the jaundice whites of Mukarobgwa’s Dying People in the Bush (1962) slip in and out of everywhere, thick and heavy like the boundary between the warm cole of Mukarobgwa’s dying and the useful clothing they dawned when living? These people are almost elsewhere, nearly specters (did I tell you about how sometimes I’ll see my grandmother’s shadow around the corner).

As you suggested, I have begun reading Jack Whitten’s Notes from the Woodshed (2018), when he said “I deny the given structure and arrive at a structure of let us say what is physical possible i.e what I can take off with my chisel… The triumph here is spatial… I managed to place color within a field without getting involved with depth of positing on the plane to arrive at depth.” Posit on the plane, I took this to mean that the shapes (forms?) became and distanced the self whitest remaining color within a field…

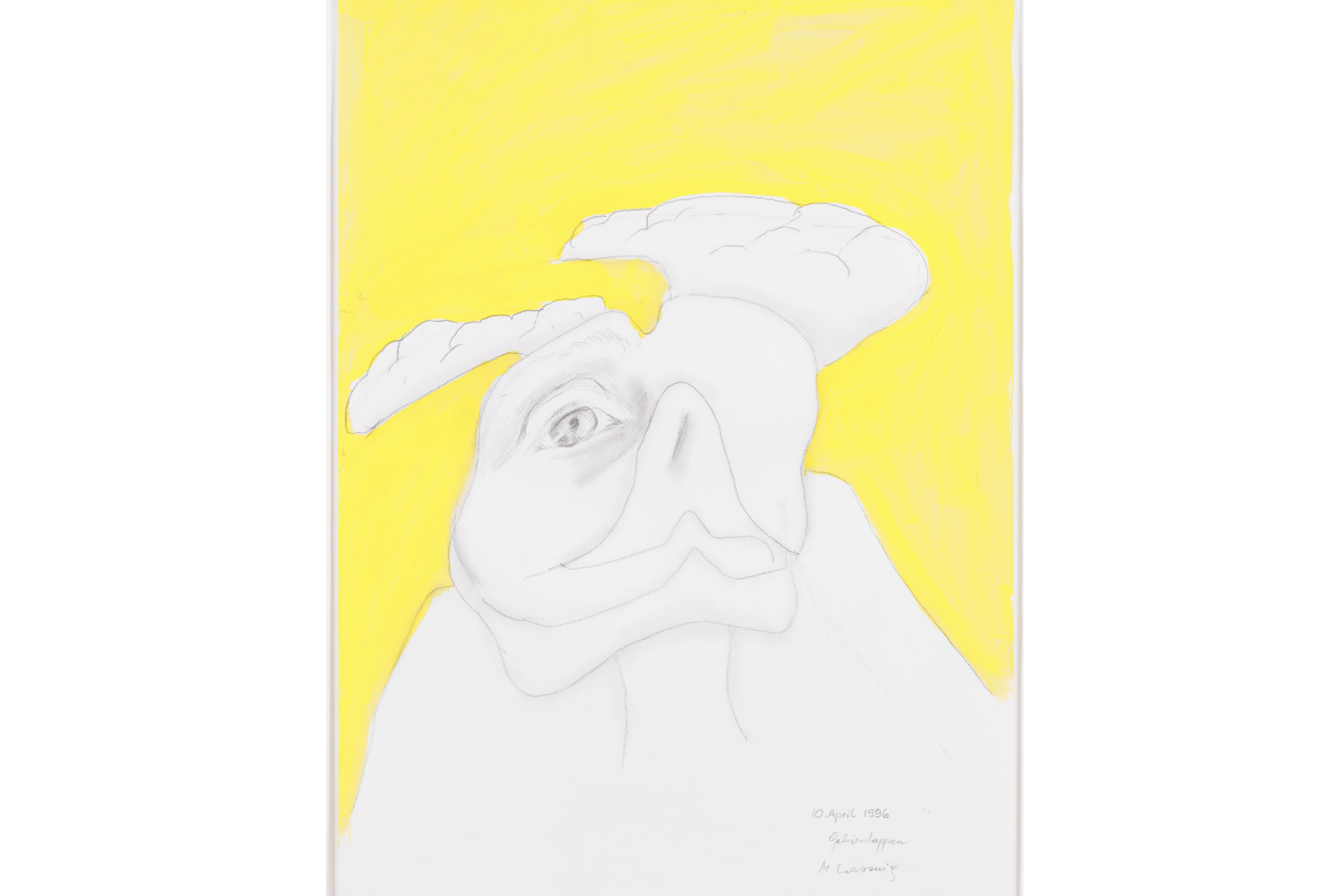

Anyway, still reading, I thought I saw Léger’s Mirror (1925), lazy-rock-non-rock-body-bits-shape-bits-frame-fugitive-heavy-ovular-quaf of a composition lay on its side and look up at me Lassnig’s Brain Lobe (1996). And anyway, speaking of that Lobe Frankenthaler has the inside of my eyelids if I produced chlorophyll, this mass of my chimera eye insides steadily wavers on the canvas, what this non painter will call cadmium exhales out into all canary, all cream, vaping me back to Jim Nutt, goading me to lay my back on Müller’s Some (2017), whose lines are happy to catch me. Smelling Müller’s baby blue curvature, becoming is the flattening and volumizing Fecteau and here we are reforming once more, an ovid mess slipping through Hesse’s No Title (1965) to Greene’s perfectly 2D Construction (1935) ping ponging around Oehlen’s Untitled (1989) and this reminds me to tell you how I was thinking the other day about how shape sometimes acts like a force of habit in one’s mind. We categorise and categorize and gloss over and gloss over until something taps us on the shoulder, all wavy and brazen and new enough to rattle us. I’ve been thinking recently that shapes and all the things that make a shape (light, the other shapes around the shape, shadow, darkness, the onlooker etc.) are bit unfixed, unhinged (leaky even), like dare I say it bodies and everything that might mean, all that slide of skin-ness. A good shape does and undoes the other shapes and we keep going within them and between them because it does feel very good to be undone while somehow remaining (done) like how I am lost in an Oehlen only to be rescued from the once luminous now near chaotic conversational Oehlen and I were having by Lucia Moholy’s Ladder Chair, sending me stepping upward to Gorky’s shapes praising one another in yellows and reds.

I am about to start reading this book whose hypothesis has already sent me down many a honey hole of intellectual stimulation, it is by Riccardo Manzotti and it is called The Spread Mind: Why Consciousness and the World are One. I mean of course this idea of oneness is present in what those white beard academics call eastern philosophy, but I just like the way that Manzotti describes it because it makes the conceit of art, especially art experienced in the 2d plane of not-being-able-to-be-touched somehow more rich and complex (if that was even possible). In BookForum, Michael Robbins, quotes from Spread Mind:

“Manzotti contends that we are mistaken to believe that objects ‘do not depend on our presence… Our bodies enable processes that change the ontology of the world. Our bodies bring into existence the physical objects with which our experience is identical. We are our experience. We are not our bodies.’ And later: ‘We are the world and the world is us— everything is physical.” This includes dreams, hallucinations, memories— all are imaged physical objects themselves… Manzotti impishly dubs this doctrine no-psychism.”

Hmm. Relevant somehow? Like in the bringing together of these works you have created for me a physical space to inhabit, a physical space where there are layers of imagined physical objects for me to see and watch flow in and out of each other through their shape, so the very perceived curvature of their perceived (or my imagined form of their) physicality. (Liquid is still physical right?)

Before I forget I wanted to tell you that I found myself reading side by side only to realize later that all the shapes fold in on themselves, flopping together in my memory till I cannot tell where I begin and the shapes end, I lose myself in them like an old lover, surprised to find myself here, emerging another self eventually.

Jordan comforting me about love tells me that love, like the world should be worn like a loose garment, ready to be abandoned only to be exchanged or worn again, later I thought this was a good lesson in looking. What I mean is just damn it I like Schnabel’s St. Sebastian (1979) despite the fact that I am surprised at myself for liking something by Schnabel, it is a very unfashionable thing to do but here I am liking. (Did my example undo my poetry?) This St. Sebastian was a clever decision, with that twisting torso (not to mention the echo of the the arrows, the martyr) and then to slide my eye downard, across Bonnard, then Munch and then Rodin’s quite frankly stunning, tiny, pins-and-needles, Reclining Woman (c. 1900 – 06). I have been meaning for weeks to ask you why you chose St. Sebastian, and instead I have spent the weeks trying to come up with answers only to realize that maybe there isn’t one, the shape was right, survive the arrows etc. etc.

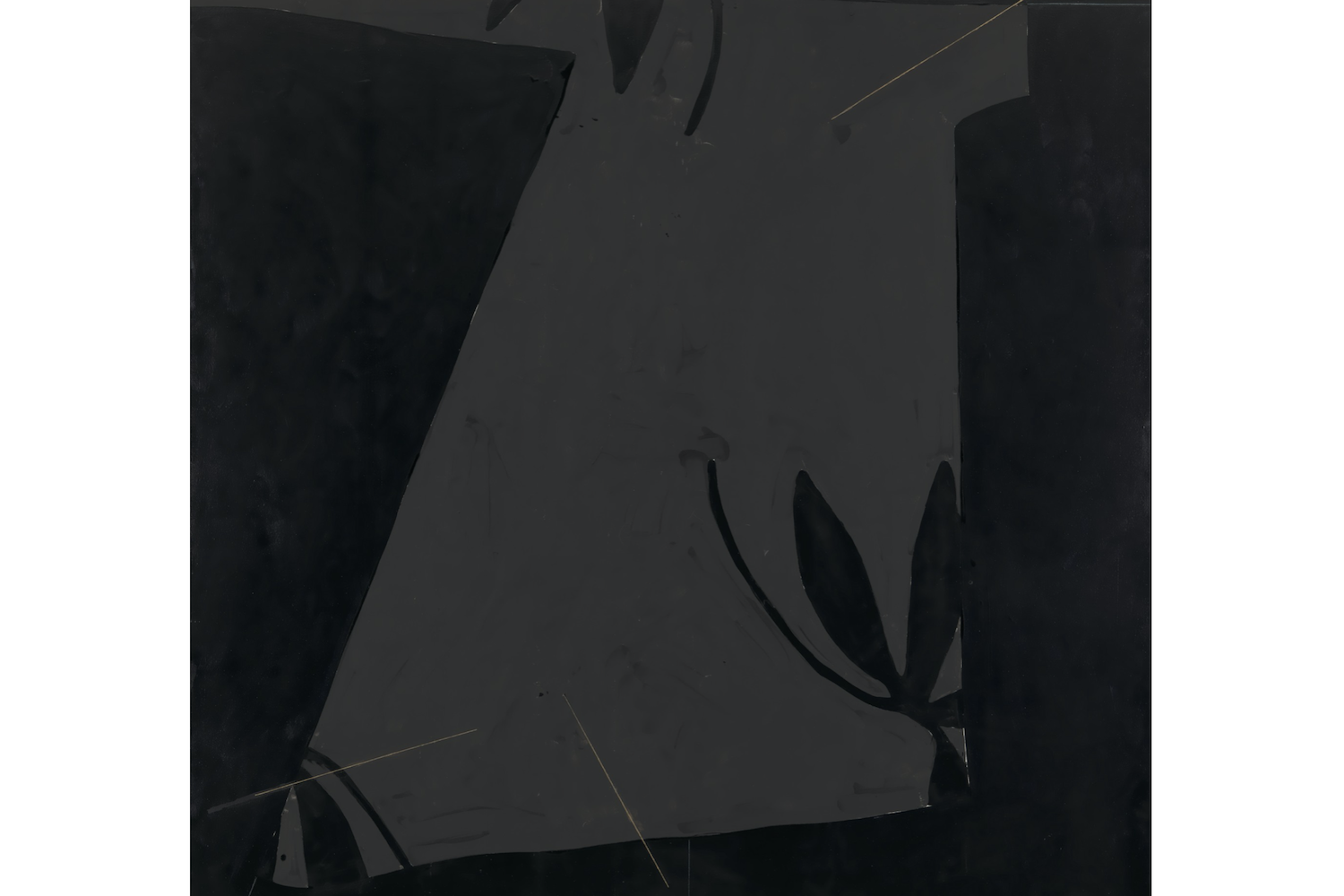

You know I love painting Amy, it’s embarrassing to love something so much. Coming down the stairs in my building today the fountain in our courtyard spun the neon yellow autumn leaves into a circle, it went leaves, water, leaves, water, leaves, water in the center, my landlord says it is broken and posts a notice apologizing. I spend the day thinking of Forrest Bess’ Number 40 (1949), the boundary of the shape that appears and reappears like little horizontal bits of water, featuring the only outline I can make out as I’m swimming, or like a drop of water on the floor. These two thin leaves sit just far enough from each other like a little spot to be cleaned up or licked up like a punishment for my adoration, or a cool shot of blissful black-bisecting-yellow water after swimming in all that blood. Then there’s Senga, fortified, within her Performance with “Inside/Outside” (1977), her shape sends somehow a peaceful liveness that feels like a tonal necessity, how they say that you should keep your muscles taut, prepared but also in the active state of nothing, subtle and controlled.

In this Calvino Story I’m obsessed with, Love Far from Home (1995), Calvino’s male protagonist describes a sort of cyclical endlessness, always he stays in the same place, always there is a landlady, always there is a woman whom he desires, sometimes she has a name, sometimes she does not. This woman, named at this time, Mariamirella, remarks looking at the man that he is both the bear and the cave; he is both the thing to run from and the thing to run to. I thought at first that this was funny because this seemed to me maybe not so much how a woman would see a man but how Calvino would see a woman seeing a man. Anyway, there is a point in the story where Calvino’s man draws a mammoth on a white piece of paper and remarks that it is a symbol but he is not sure what it means. I was thinking the mammoth, named or not became a shape as it has no designation not meaning really, it is mammoth and it can be redrawn over and over. Like the authority of this hand that shows up in Valie Export’s Cycle of Civilization. The Mythology of the Civilizing Processes (1972). That hand shows up too in its own way in Applebroog’s 12 part charcoal Couples I (1983). Choke the man who thinks he can know what the woman feels. Choke the man who thinks he can know what anybody feels. Too much hand there? Too much narrative?

So much is happening in Couples that I think I become part of the chaotic movement between the two of them, obscuring my own understanding of the blackness of what I suppose must be a darkness ascending upon the two of them. We’ll go back and forth like this me being the darkness and the two of them actually creating it until I am pulled onwards again, still reading, arriving at the watercolor Picabia, Conversation II (c. 1922), letting that fuse with Valie Export’s Encirclement from the series Body Configurations (1976) into this kind of swooping armature, that spins itself right into Edward Avedisian’s sweet acrylic freak, The Whole World Has Gone Surfing (1963) and it is here thinking about how insane it might feel to be surfing with the whole world, that I nearly stumble into Anne Truitt’s First Requiem (1977). This reminds me of this idea you were talking about the bursting room, that they (this crowd I’m talking about) had to do something together, all the things that I think are implied in this phrase “do something together.” There’s so much wound up in doing something together, the push and pull against one another, the kind of full throttle heavy breathing of rubbing up against another something… You said you did this fast and I’m glad you did because speed and fury feel like good little measuring tapes in my current life and living tool kit, I just have to make sure I don’t back into any sculptures. Whatever. I’m in a desire spiral, I desire and I push and I make and I keep going and if I take a breath it’s only to look at the sky or stumble into this tall calm Truitt, simple, floating, slipped in green or was it yellow (so hard to treat this shape in any dimension) Do you think maybe Truitt was looking to suggest another possibility for dimension, obviously in relation to painting but also in relation to the space where the painting is often viewed? Self-aware, complicit, complacent, is that a painting if when you look at it it feels flat but stays within itself as a 3 dimensional object and being (inhabiting two states at once visually and physically). Am I reaching? Where’s the shape? Is that what is actually happening, I’m hoping yes. Maybe your Arp is doing that too, at first blush, from that one centered angle all the masses in the Mess of the Arp leave it to inhabit the others in the crowd, or they left the others in the crowd to inhabit the Arp, whichever way these things swing at any given moment.

Within we do and re do, over and over until we cannot anymore, visit each other in a dream, see the color, the light, repeat. When the surface gets right inside your mouth, when it gets inside my mouth, I open up and the key is to swallow till you choke or I could say it another way. Sometimes when I’m making work, the work and I trade jobs holding each other, propping each other up or something like I make my own lovers and sometimes we quarrel or something like that… it makes it hard to have human lovers.

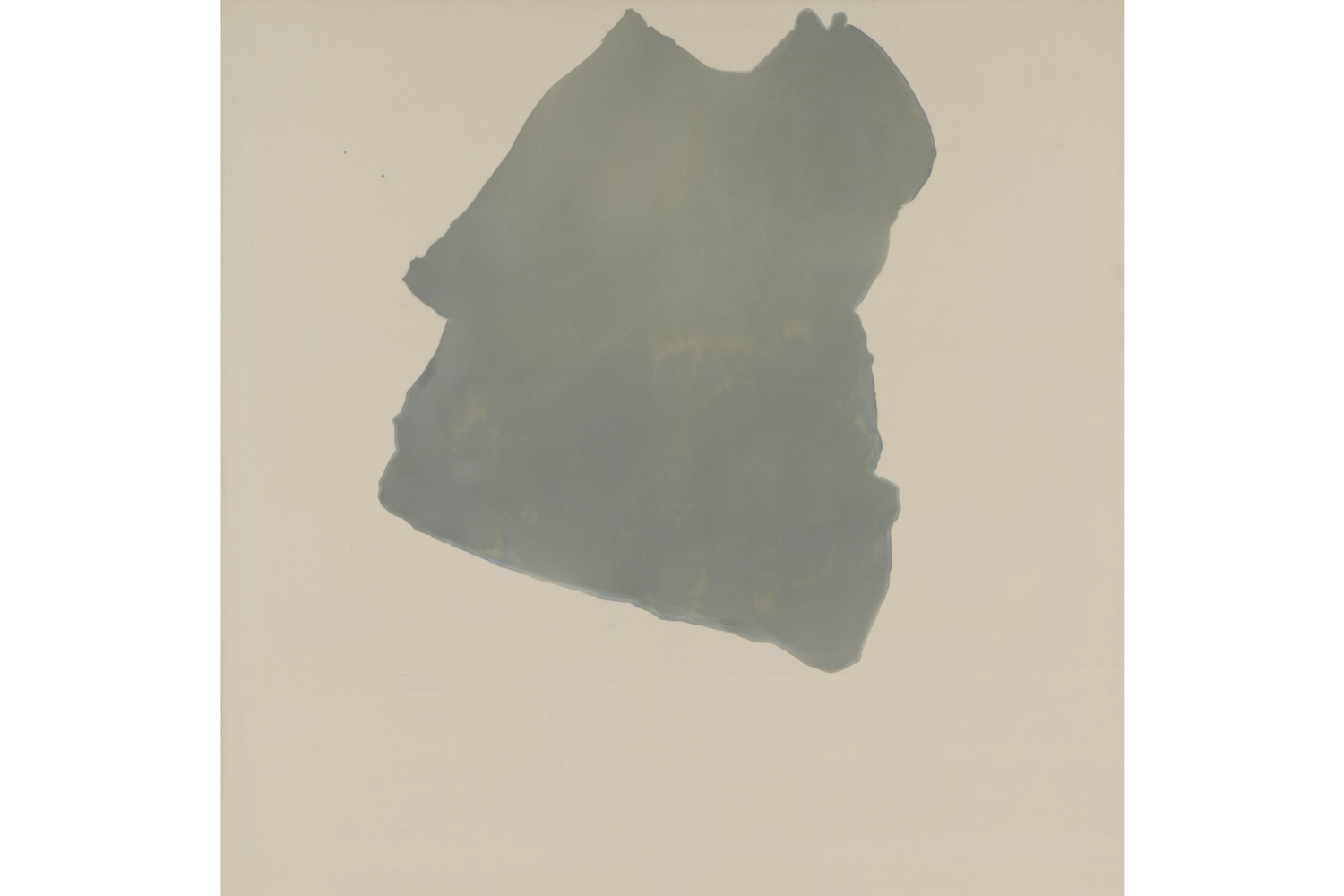

The way that Dove sits is like a lover in my mind, high and almost impossible. Impossible that a curvature. Saw in bliss can arrive again in Dove’s longing, undulating bulges. Willows he called it. The other morning, towards the end of last year, towards the end of that autumn that was essentially a continuation of summer, I woke up to see the sun hit hard the shocked itself to orange of the leaves in the trees in my window, with the sun they moved in such a way that they remained flat, grouping themselves together like a pack of spinning sardines and I laid down nude with my back on my wood floor looking upward and I thought about how these little moon shapes, these leaves-sardines, reminded me not just of the shadows during an eclipse but of Dove’s dialogue with that Gorchov you chose, Comet he called it and how Comet is the further point of the slow total inversion of Dove’s Willows, with Forrest Bess’ 40 listening in from just to the left, mining all the things between them into the sensible placement of that perfect blue that dare not be a fish and the garden sword prickly phallus that lays flaccid-erect and where was I, right yes balance. What is that Popova (Untitled 1916-17) doing up there in the corner? It’s “failed” square cross pointing me downward to the stalemate between the red oblong almost triangular spouts of Louise Bourgeois and Alexander Calder’s two Untitleds (1950 and 1943 respectively). Ignoring the aforementioned chronology, Bourgeois and Calder are making a chicken or the egg game out of their private shape conversation arguing a little while everybody else seems unphased. Meanwhile Kobayashi’s Three Plums 1984 (found pressed-tin and nails on wood) FOUND of course, well we all know what happened to the plums in the icebox. I turn again, stumbling around the Truitt. What shape is Truitt now? Barely there actually, flattening as if Ulrike’s Some has slipped into a flat, plane based embrace or; I am so close it is basically between my eyes and now here I am looking back at Frankenthaler, and that green now looks like the foggy haze of an English garden, manicured and landscape, very Connecticut, like the view from Johnson’s glass house which my 3 hour tour our guide informed us they would often have lunch parties where they lounged about the garden, making themselves pieces of the landscape. I took this to mean they were having orgies (probably), seeing bodies populating that big English garden landscape like a big sex filled near sided Rocco monster (Off with their heads! but their heads (queer? Are they? If so are they then also related to mine?).

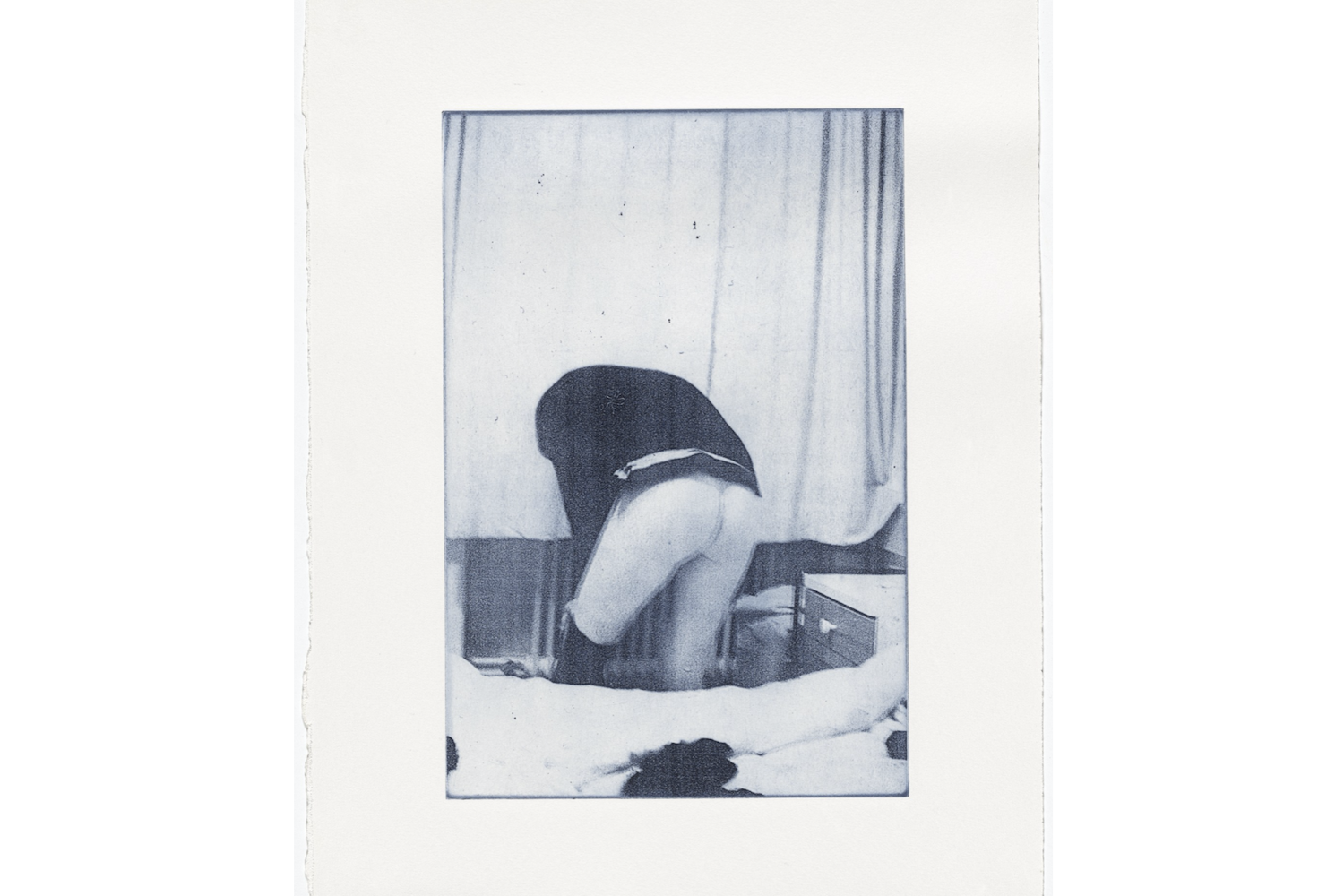

An orb reaching outward and now forcefully and purposefully I stand myself in front of Chris Ofili’s The Raising of Lazarus (2007). Is it the charcoal that is making this vibrate so intensely or is it the nearly nodal shapes that you’ve seen here within this Ofili, the hair skin sliding down the left of the canvas, the legs becoming other legs, or vines or plants or all of the above. The shapes inside of Ofili’s colors get me thinking again about the date I took myself on to the Prado when I found myself in Madrid a few months ago. In front of the Bronze Hermaphrodite that Velasquez had commissioned I remember thinking that their body was fluid and inky, slipping in and out the covering because their body was stone. Then as I’m thinking about it, I realize that the perfect mustard waterfall which hugs the purple ass of one of Ofili’s figures is a near inversion of Goya’s drowning dog and here I am again thinking of the way Goya painted skin, all orange and pink in tight curls, swathes of fussy pea greens amassed to make the color themselves, just thick enough to make a shape. And all asses and curls and fussy, here I am in the corner of butts, or asses or behinds or whatever. Eielson’s White Quipus (1964), a body on its side, pulled forward into being by that flat black separator which you’ve placed sensibly hovering over Matisse’s Bather (1909), which is inverted effortlessly in Christopher Wool’s photoetching Untitled (for Texte zur Kunst no.15) (1994) and all of this to be led to the echoing twins: Rothenberg’s distillation all void in center and everything, Untitled (1977) and Richard Tuttle’s New Mexico, New York D #13 (1998), together it is as though all the shapes in the corner went swimming losing their face paint.

Lois Lane’s Untitled (1979) somehow in this big aggregate feels like it could slide off the wall at any moment and when it does, it’ll make a sound that we won’t be able to hear. The same way I can barely hear that light line shaping through the Eielson, through Matta’s My Blind (1946 – 47) and straight into the shadow of Lane only to be picked up by Lane in a slightly more yellow (nearly the same jaundice of Mukarobgwa’s Dying) all to send one of her black frame inducing rectangles so askew I think “jeez fall down already” and all of this, the reliefs, the dying yellow lines inward (and outward), funny how these straight lines in Lane push me to feel a relief when I slip my eye over the gentle rolling black hillicks of Baziotes Pompeii (1955). Whitten said in his studio journal on May 17, 74 “The circle is my absolute.” I underlined this and thought about it before sleeping into my jet lag, falling asleep and then waking up in darkness only to fall right back asleep again, spinning myself into a wave in my partners arms, listening to the roar of my kid snoring-sleeping in the other room. I’ll do this again tomorrow I think. Funny skin can smell so many ways.

Here I am now caught between Elizabeth Murray’s Up Dog (1987-88) and Bearden’s Patchwork Quilt (1970). Murray’s almost magazine 3D seems already in motion, like it’s been going for so long we’ve given in and let the dog up on the couch only to find that that didn’t settle him down. Meanwhile, Bearden’s big blowing together of shape into a being, tenuous and fragile but solid and static behind that glass, lounging like a memory or a voice I’ve heard before but never actually heard (my mom swears she can tell when she is speaking to a black man on the phone).

(I guess you’re starting to gather that hanging out with this crowd you’ve assembled, all this looking at them is a total free fall for me, Amy.)

And here I am lapping up my own fall, diving into the plump-pushing-together of Prunella Clough’s Stone (1985) to get spat out right onto Charline von Heyl’s Igitur (2008) only to slide all right angles and big shoulders into Louise Nevelson’s That Silent Place, filled with painted wood, dense and heavy like a scotty dog.

I’ve been meaning to tell you this too: I went to Amsterdam where I read with my friend Riet she just released her newest book the correspondence to the artist Grace Crowley. Crowley threw out any letters she had written… her best friend called her smudge. Anyway, Riet and I read a conversation that Riet put together, Six Double Lines, where Crowley and the artist Marlow Moss discuss their lives through the categories that one might use to classify a life (friends, father, mother, schooling, pets, mentors, lovers). Do you know about Marlow Moss? About her life with her lover Netty Nijhoff and all those beautiful paintings that she made, an abstract artist sliding around Europe around World War 2, living next to Mondrian and becoming his closest companion for a time. Their work swelled and flowed into one another, but she thought about things distinctly differently from him. Anyway, I bring up Moss because Riet and I were discussing how can we speak about Moss without having to constantly put her in context as “the woman who is accused of being Mondrian’s plagiarist.” (She wasn’t and that was just one facet of her life and her painting). How do we explode the discourse while still acknowledging all this Mess? (By Mess I mean the fact that Matisse can really render the full complexities of a butt.) You wrote to me the other day something along those lines about this show, about saying of course, the canonical monsters are beautiful and fun and many things but what kind of vacuum has been created to sustain them as placeholders of enormous amounts of money, there is so much else we could be looking at too. My friend Rose told me the other day that a grouping of lizards is a mess and later I learned a grouping of cheetahs is a coalition.

In this whole thing it feels like your hand is squeezing the back of my neck, every now and then whipping me across the room or sending my eyes circling around themselves, letting me slide into the dizziness only to shake me up again. Asking me big questions like can you feel the ground beneath your feet? Can you feel what parts compose the ground?

I think so.

A ground on which one might plant themselves on,

If my mind is quiet and I look at one good work next to another good work, I can feel them crashing up against one another, the way I can feel a ram hit another ram by seeing the echo through their bodies, ripples of hair.

I don’t know, do you think this is relevant to the shapes: this thing happened to me on the plane to New York this last time where I found myself sitting next to someone who found me cute from the moment we sat next to each other and since it was the kind of flight where it is expected that you sleep on the flight we found ourselves faced with the opportunity of sleeping next to each other and after we were served what could have been called pasta and I drank a red wine at what my body believed was noon, they looked at me and very casually took the arm rest separating our two seats and lifted the armrest up, “is this ok?” “sure”, allowing our arms to touch and our knees to knock lightly against one another while simultaneously giving us both much more room than our economy plus seats advertised but to get all that room we had to be ok with touching one another and we were and we just did that, put on our noise canceling headphones, listened to whatever it was we were listening to, closed our eyes and rubbed up against one another in our sleep, grazing, touching, until exactly one hour before landing in Newark when the harsh house lights of the plane came on, revealing how deeply we had interwinged ourselves with one another and we had no shame about it, gently untangling, opening the shade to reveal daylight and I asked the steward for a coffee and they for a black tea and we both went through customs without issue and they didn’t have a checked bag and I watched them walk away as I waited for my bag to clunk out off the conveyor belt on to those familiar metal fans of the waiting baggage claim, pulling in and out of triangles, exhaling around each turn. I wondered briefly where they were headed and then remembered to text my mom to say that I’ve landed.

I’ve been around more babies recently and what I like about having babies around is that they are discovering always the phenomenological realities of being (excuse me for the art speak), the wind on your face, the difference between wet and dry, the way that lights moves through the trees. A baby I know, a calm baby with an easy demeanor whose ability to see was strong and so it was a pleasure to be around her, I watched her watch the light move through the leaves, she didn’t quite smile as if notate, raising her hand to see if the light would move through them as well.

I was talking to my friend Harry about a little of this, about how much I love painting about abstraction and why I demand of myself to continue to push every boundary of what that might mean in my painting, in my sculpture, in my films and why your dedication felt like an important call a reminder NOW RIN NOW NOW NOW! I am a painting guy but I don’t think we live in patient times (did we ever?) Shape prevails (like you say) because if we are uncertain and we are vulnerable we keep ourselves open, we chart, we mark, we make, we overlap, we double back, we look in the mirror, we pinch our fat, we wash our clothes, we talk to our dead friends, we ask them their opinions, we wake up tired, we wake up hungry, we don’t mind, we meander, we look at the leaves in the trees with the baby, we wake up every day and push paint around and we’ll do it again tomorrow and the next day, refract, refract, refract.

Anyway, thank you for always being up for the conversation. I hope I haven’t offended you with my extensive wanderings.

As ever and always, more soon,

Rin