Growing markets for life coaches and physical and mental hygiene apps suggest that today’s digitally dominated consumerist society is chasing an emphatic concept of life. Appropriating alternative modes of living, Ulla von Brandenburg’s latest installation seeks to provide an answer. Presented as something like an ethnographic fantasy, von Brandenburg’s show presents us with an imaginary community, evoking communal back-to-nature lifestyles promoted by Europe’s “life reform” movements at the dawn of the twentieth century.

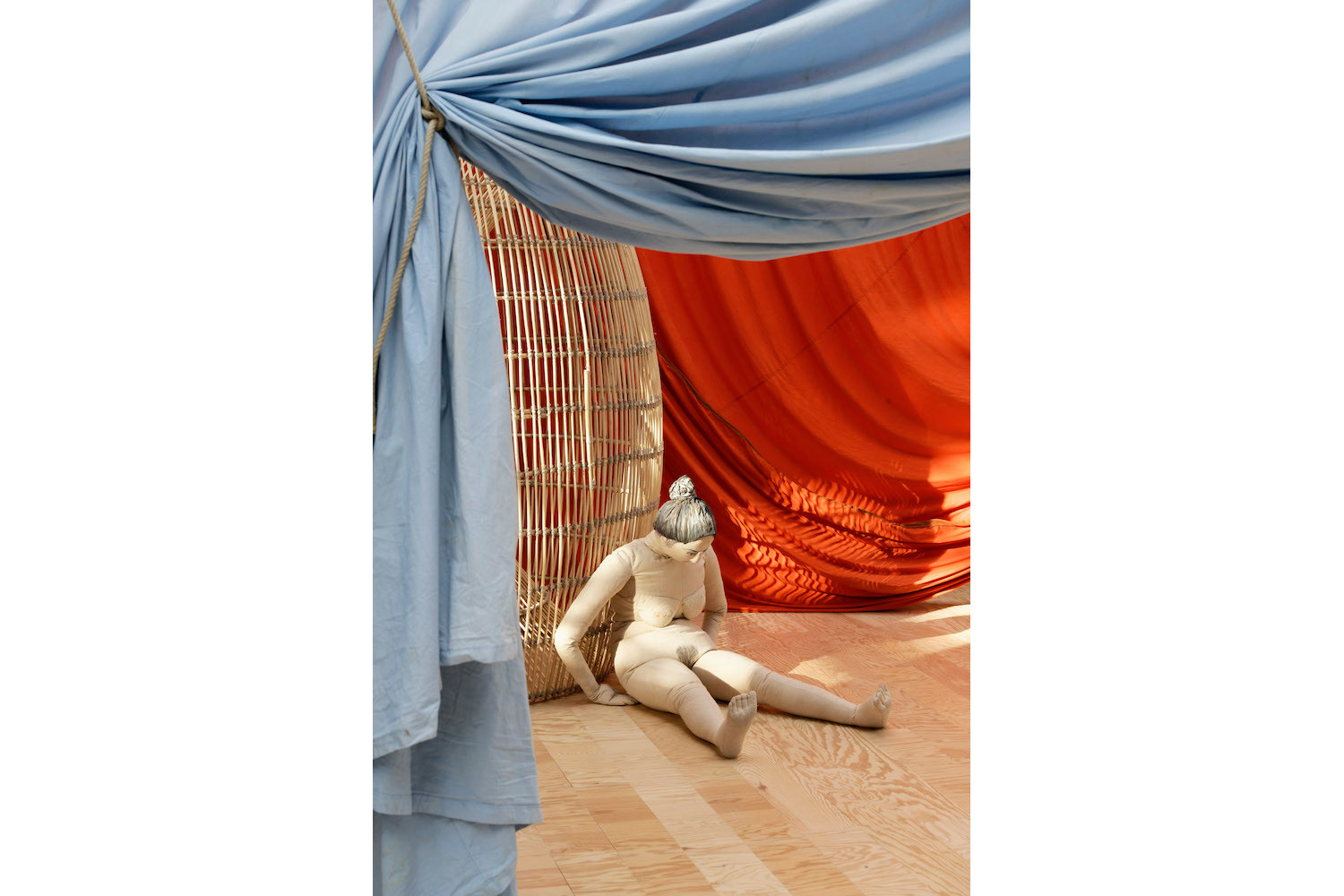

Carmine, lilac, indigo, and ocher, glowing in the museum’s abundant natural light. “Le milieu est bleu” (the middle is blue) above all is a harmonic system of colors. Upon entering the main hall, we pass arrays of monochrome curtains, monumental in scale and yet light and welcoming. A spatial metaphor, which in theater marks the threshold between reality and imagination, here orchestrates our encounter with a group of objects scattered around the installation’s wooden floors.

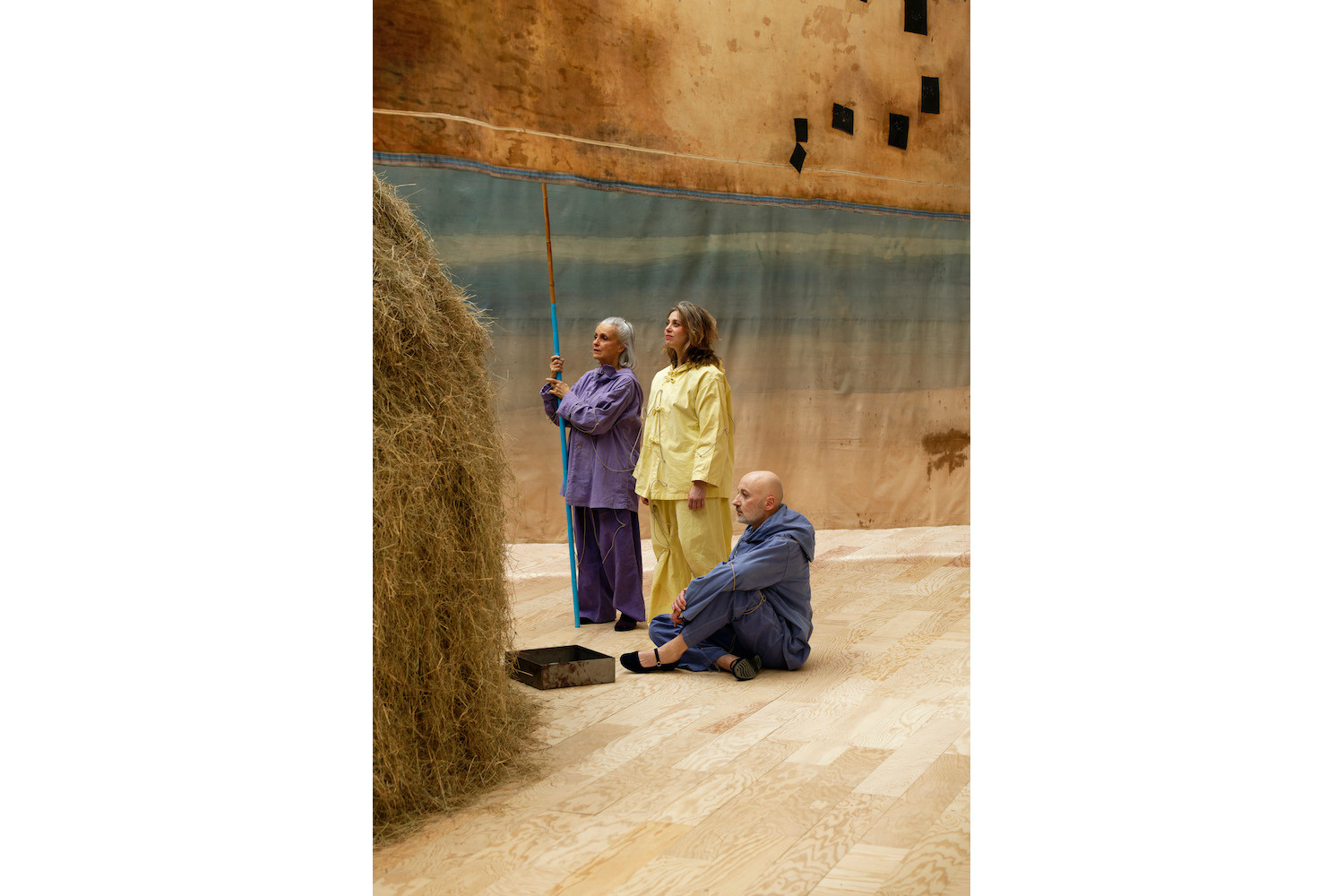

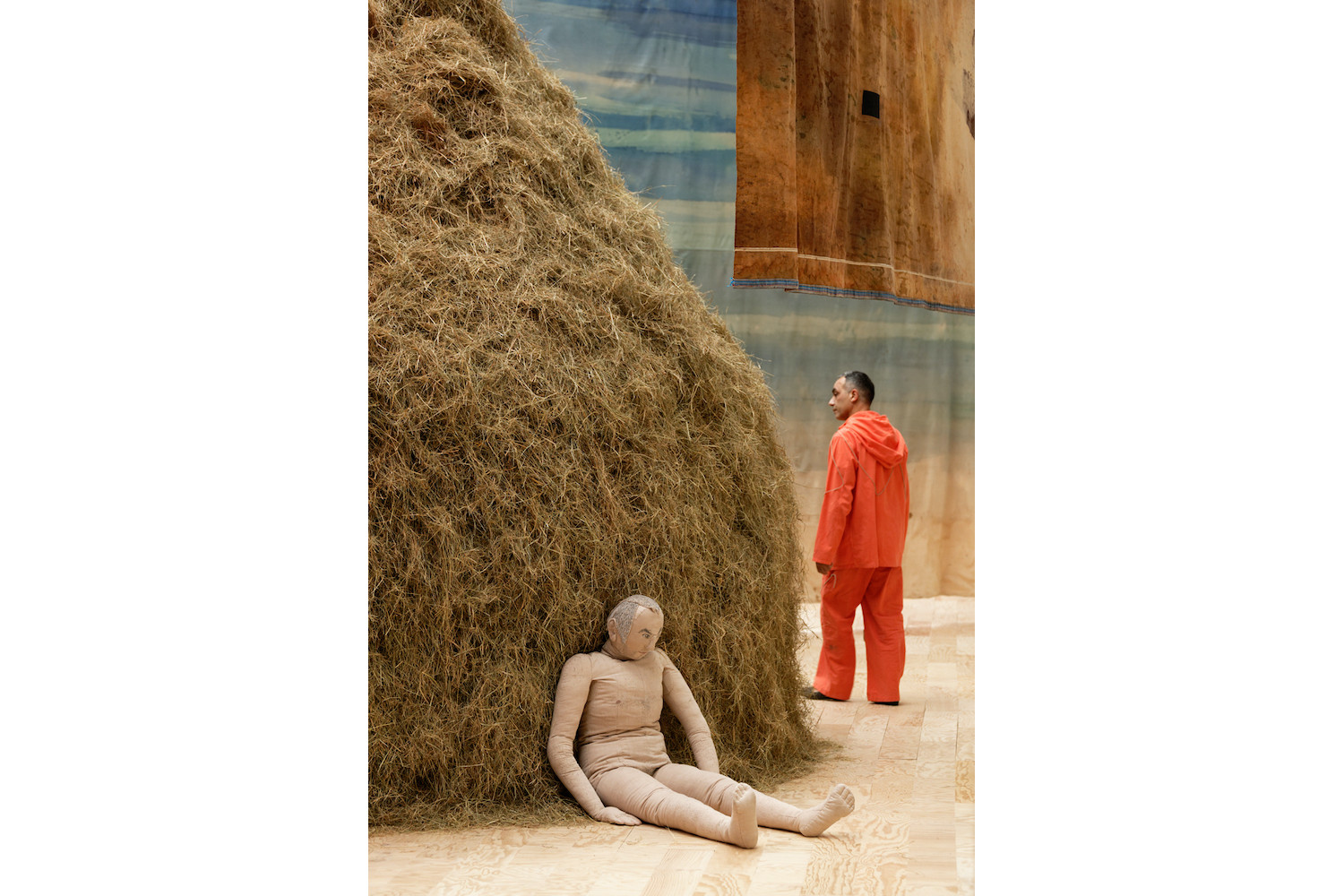

The first one I find — lured in by its hum — is an automated shruti box, surrounded by what looks like giant blackboard chalks. Adjacent to this first enclosure a haystack emits the exhilarating aroma of a rural idyll. An oversized wooden fish trap has life-size textile effigies of two naked women propped up against it. While objects such as colored sticks and sets of rolled-up ribbons suggest ritualistic use or play, these uncannily realistic dolls serve as placeholders for a group of performers who weekly rework the show’s spatial arrangements. The same characters appear in a video that marks the end point of von Brandenburg’s Gesamtkunstwerk and serves as a key to the ethnographic research that inspired it.

The video’s site is a popular theater founded in 1895 in the French Vosges. With its inclusive pedagogical concept and a stage opening onto the forest (conflating both stage play and nature), Bussang’s “Théâtre du Peuple” invokes the transformative power of art in the service of mankind’s emancipation. This is the setting in which von Brandenburg’s performers can be seen handling the same props we had just encountered in the installation, as if preparing for a festivity. Their bustling activities culminate in a dance ritual revolving around a blonde, radiant woman, dressed in yellow, cocooned within a fish trap. Everything appears arcanely symbolic. Their chants hardly help as clues: the artist has put cryptic German phrases into their mouths (“the donkey lied, the boy rose […] yes-no, yes-no, no-yes, no-yes”), pronounced as if spoken without any understanding of the language. What translates beyond von Brandenburg’s artistic encryption is her community’s different take on property and togetherness.

Recently, artists have been taking an interest in exploring less alienated ways of relating to the world, its objects, and each other. Berlin’s Martin-Gropius-Bau set off its 2020 program with “Rituals of Care,” a performance series featuring experimental choreography, healing practices, and collective gatherings. Concurrent with von Brandenburg’s show, Jeremy Shaw presented a fictional survey of cult-like modern dance movements at the nearby Centre Pompidou (“Phase Shifting Index”). In line with such efforts to turn “exhibition value” back into “cult value” (terms coined by Walter Benjamin), Ulla von Brandenburg continues an inherently modern quest: how to redeem art’s transformative power –– once stripped from its embeddedness into belief systems –– without fetishizing mere décor.