There are no sacred cows in art. Every practitioner follows a plan of sum totality while at the same time proffering sliding-scale rules that bend tautologies as they affirm them. The best formalists have a way of injecting life and idiosyncrasy into droll repetition and protracted serialism. They hunger for self-effacement as their ascetic labors quietly emit internalized eureka moments. That innocuous space between something and the seemingly nothing has been ably conveyed through the reductive spaces we’ve come to know through Minimalism. Emptiness is an imprint of the void, both as literal impression of negative space and the support and ground that transcribes its parameters. Artists far and wide have engaged with its mysterium, a culmination of the modernist project deconstructed and jerrybuilt with formal purity.

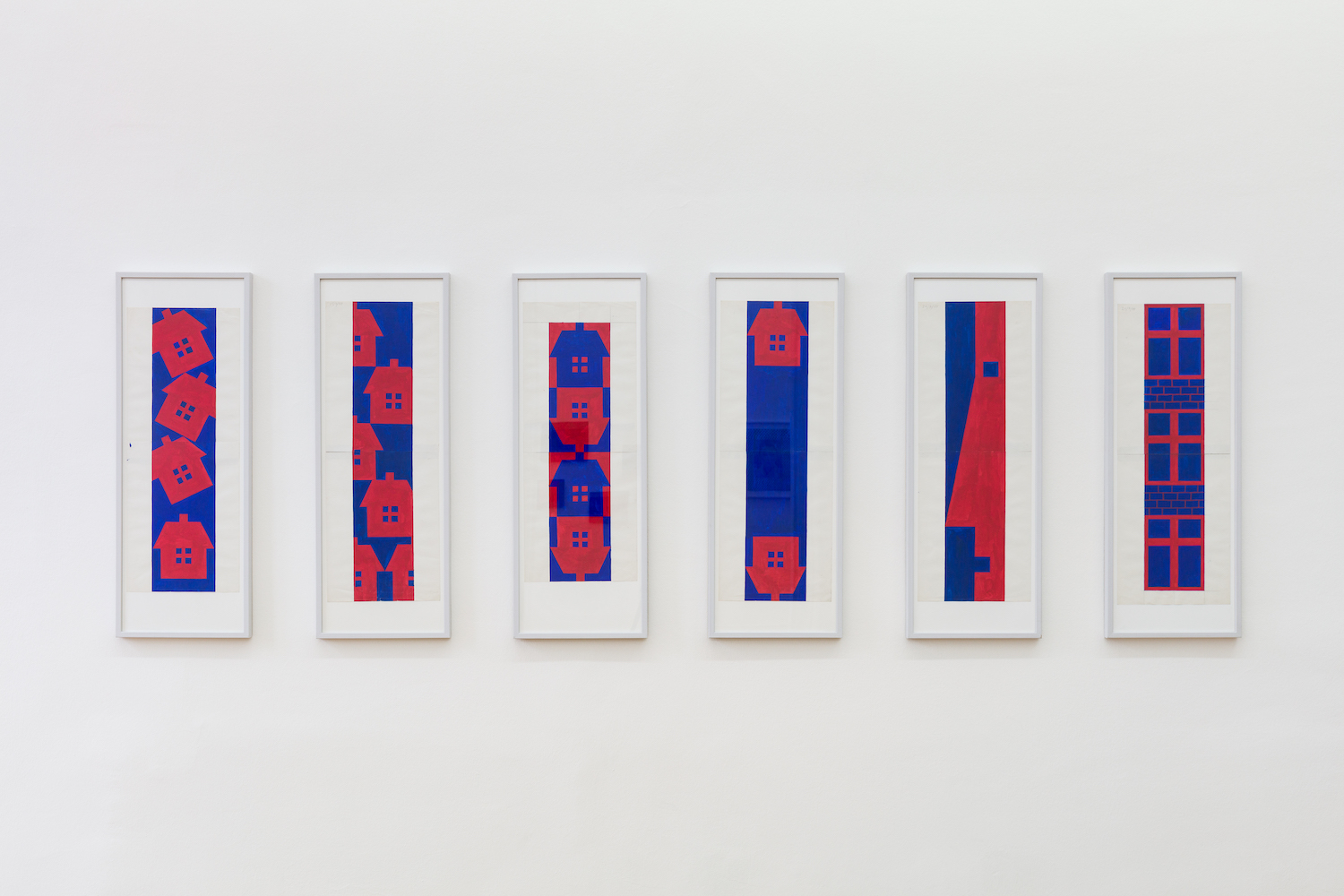

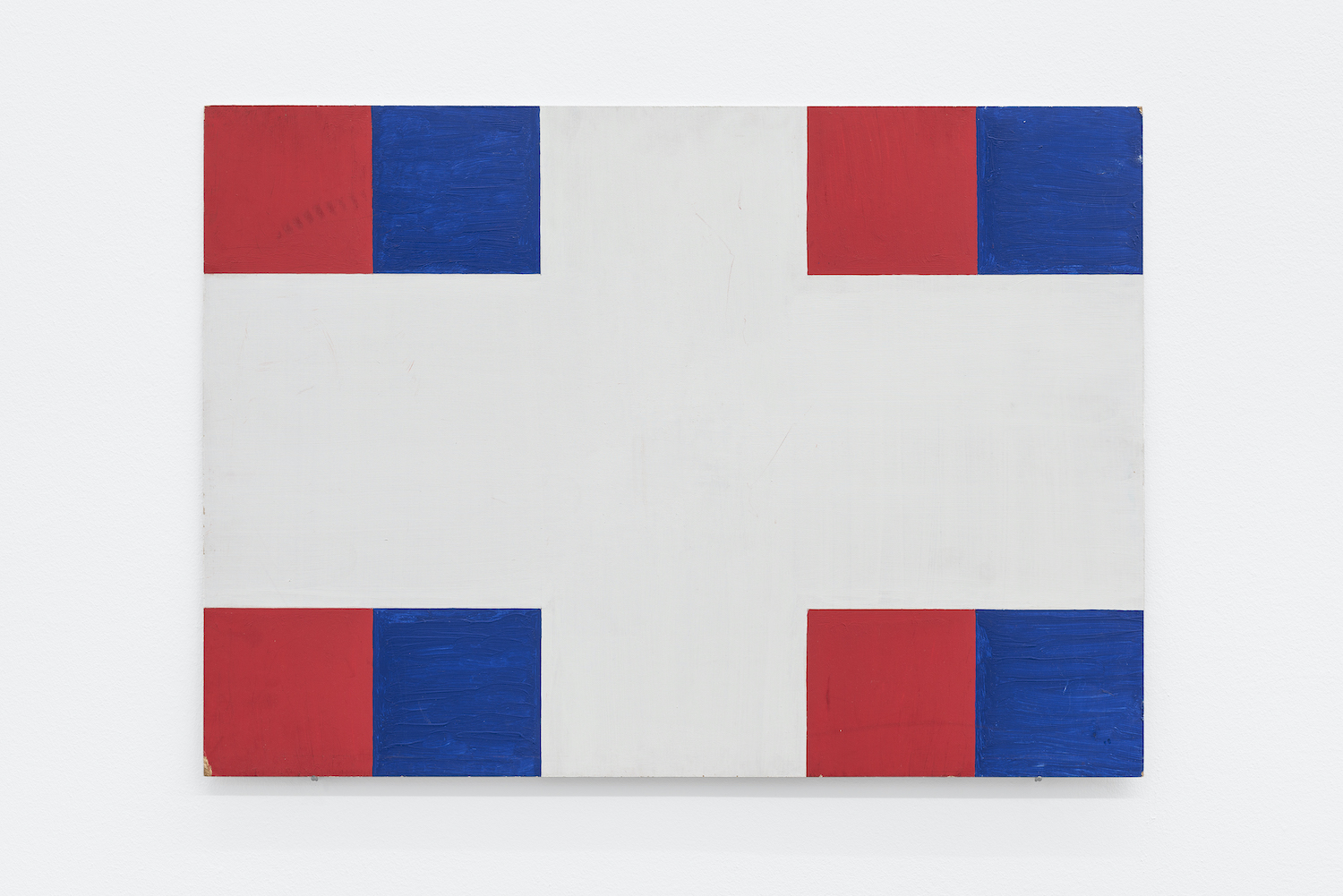

Simple materials are the poetics of artist lore: modest objects on the one hand, declarative ideas on the other. The young Albert Mertz matured in the milieu of the European avant-garde of the 1960s, interpreting the interstices of American Minimalism, Pop, and Fluxus. His oeuvre was a Nordic antithesis to Minimalism, cherry-picking its lingua franca for his own rational amalgamations that filled in minimal blank spaces with the white noise of information. These reconstitutions of graphic input and mirrored geometries are the muffled sounds and editing of illusionistic representation. The lines of De Stijl and Constructivism are co-opted with a snug domestic twist. Windows and houses are themes in the most rudimentary sense, like road signs signifying the dualism of interior/exterior. Face profiles make the case for human interaction and thought within a system of keyboard-style icons, which in Mertz’s case presages the emoticon. Groups of modular paintings are painted on the horizontal hard backside of drawing tablets that retain their spiral wire to offset the small hard squares within.

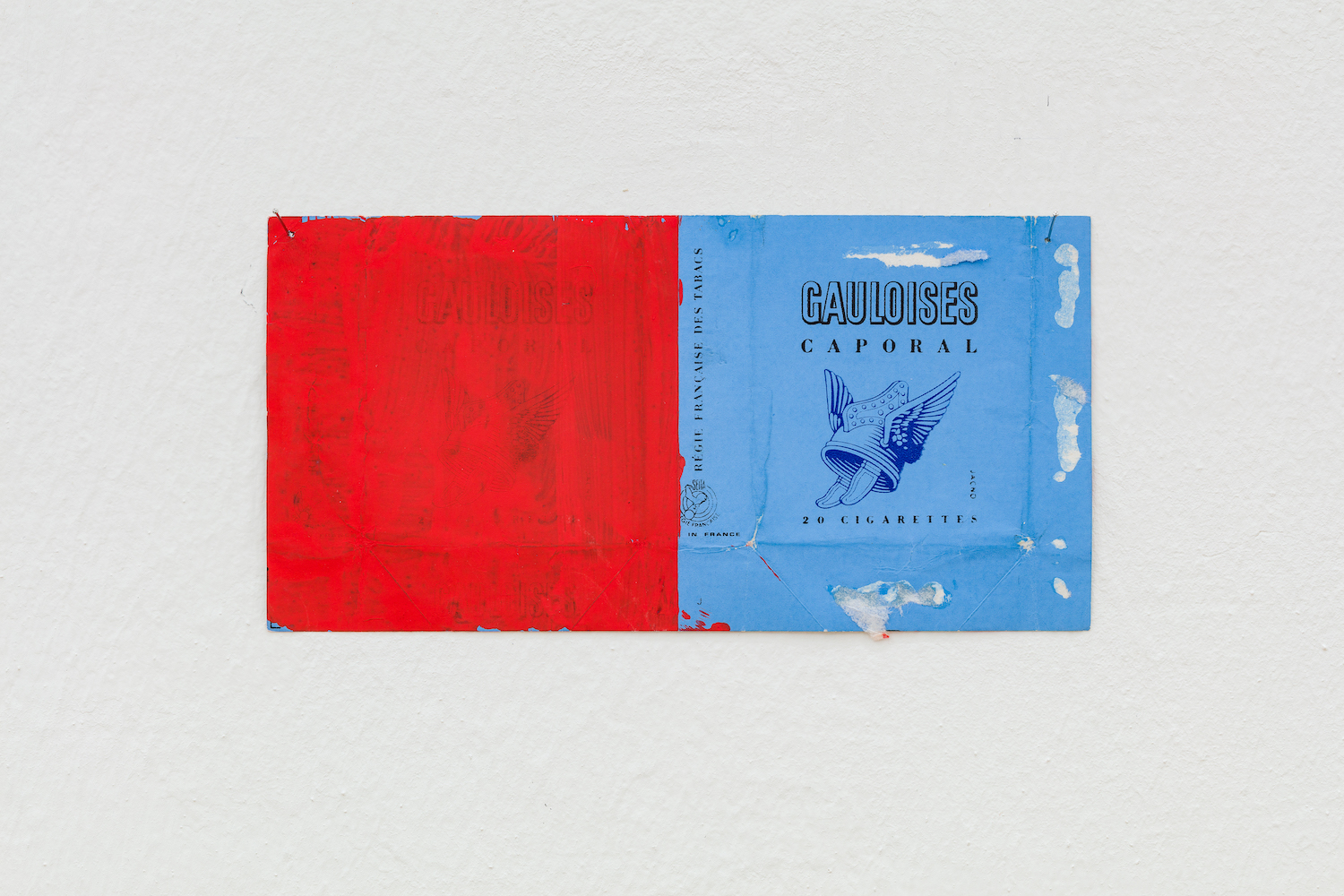

Using a limited palette of primary colors, most often reds, cerulean blues, and occasional punchy ochers, Mertz might be described as the brainy nonconformist cousin of Blinky Palermo in his use of signature forms to great affect and subtle variety. With this economy of style he marched to his own peculiar beat as the odd man out, a hiccup from ascetic Minimalism. More of a priest of the world, he retooled whatever suited his fancy and played with preset structures. A baby blue wrapper from his preferred brand of smoke, Gauloises, is unfolded and demarcated with translucent red gouache to its left. The unfolded and flattened paper is hung on the wall just so, like a painting.

Correspondences harmonize in the overall presentation. Repetitions take on an optic of rectilinear to-and-fro. Flatness is its god. Vitrines of graphic ephemera and catalogues attest to his output and long career, marking this revelatory survey exhibition on his hundredth birthday. The Mertz system of patterns and grids are not so much careful studies of color and form (in the manner of, say, Albers) so much as they are the haptic mentalism of a detached observer of the signs of the world. Two Nordic beauties culled from glossy magazine pages are collaged on paper with an array of Benday dots hand-painted across the surface. Faces and places, structures and supports, squares and rectangles, verticals and horizontals: all composed with an analogic lightness of touch.

That aforementioned domestication feels very at home here, as the gallery itself occupies the well-appointed spaces of an antique, high-ceilinged apartment, its baroque parquet floor of another era. Mertz (who passed away in 1990) lives in the lucid dream here. Without egoism the hallowed recollections have been faithfully set down through his cerebral apparatus. Life was anti-spectacle for him, its daily rhythms distilled into hieroglyphs resonant with the shorthand communication of today. This period of his career is fresh as a newborn, and reminds one that our time on terra firma is so brief, yet so indelible.