In She’ll (2013/2020) a room becomes a plinth; it is a replica of the internal dimensions from Ian Law’s bathroom of his childhood home — the only lockable room. She’ll forms negative space yet it lacks imposition; slim and sage green, it seems passive. Inverting the proportion of support/object, frame/content, She’ll hosts an imperceptible potpourri infused with bergamot, mandarin, and geranium oils. The practice of commemoration appears at work, and yet it moves on — the potpourri persists in the present.

Law’s tone is complex: restorative, ethereal, diffident, slightly melancholic. Here, Law deconstructs time to restore content from incidental dissolution, giving new forms to the process of remembrance. Events are eschewed; Law’s eye seems taken by absence, ephemera, the everything else. Lining three walls are Bath Text (i-xiv) (2020), a work built from accident: dropping a book in bathwater, staining 1,500 words in pink, cauliflowering mold, Law transcribed these lost words to form poems.

Remote and clouded, these texts are bruised by spectral, misaligned interaction, the quietude of whoever’s “self” might be positioned here marked by the unsaid, burnished by vacancy: “this effect holds to remoteness / as salvation / leaves like a fume / I ground this dream / and smell its vacuum.” Bodies are sites of possible exchange, but the “I” looks for an exit: “when my own existence seems unreal / a manifestation of his desire / I excuse myself”; amyl stirs pleasure, maneuvers energy between others and yet the subject is resigned to killing time. These little tests of intimacy are perpetually cushioned by evasion: “I journal into him … striking towards my loss of substance / humiliating silence / drips the room.”

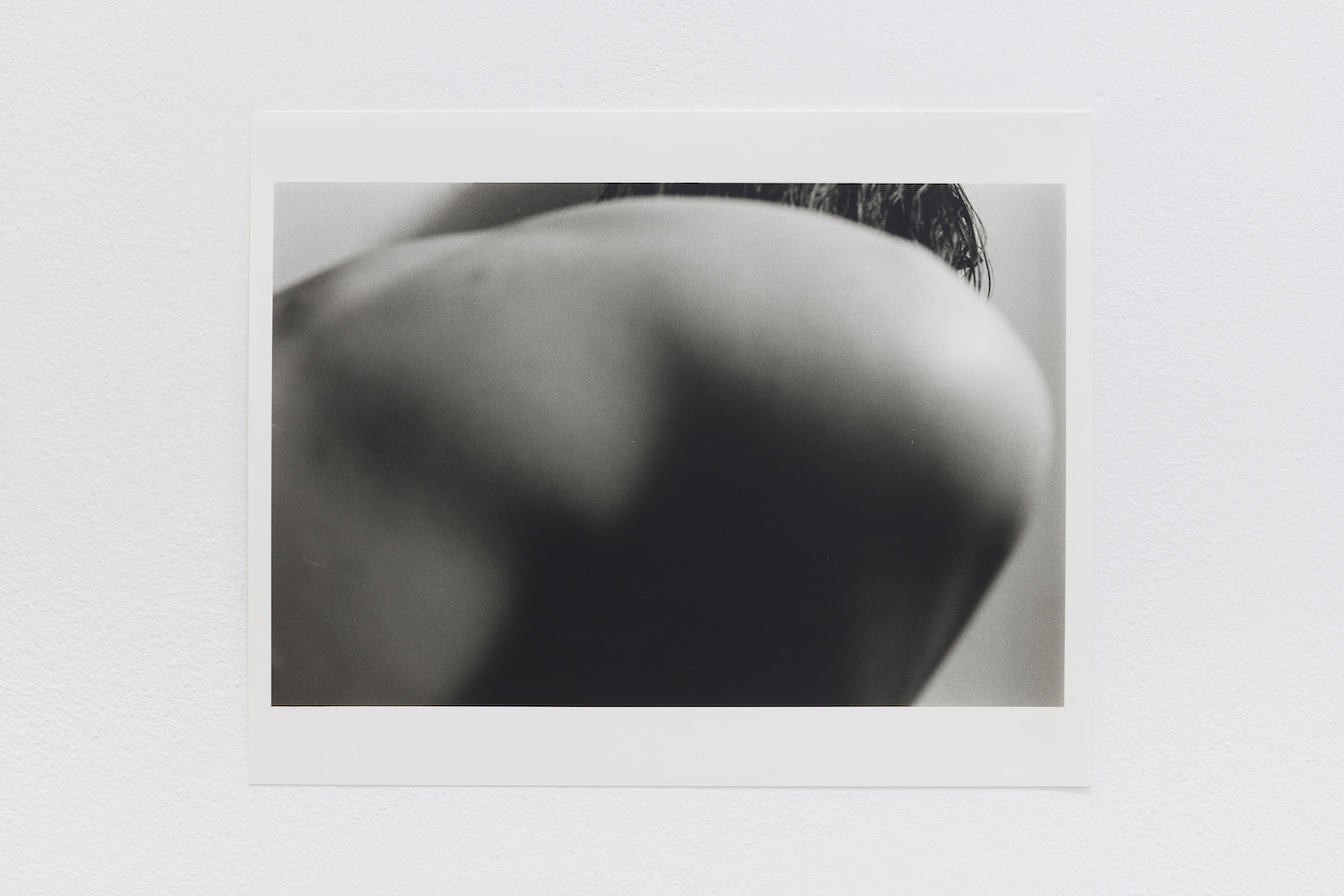

The gravity of interpersonal impressions is vague and when the body comes forth, its inferred infallibility is denied: “a prefiguration of desire / renders the tension in my body / armchair, taciturn.” Touch, rather, seems found in accidental recognition and reconciliation, the charmed moments that admit the feeling of time’s passing, like the shifts in consciousness summoned by mourning.

“Drips the room” detects the condensation within containment, the little furnishings that serve privacy as relief, whether sensorial or syntactical. Like the isolated bathroom, there is a collapse of time and space — things that remain dried upon the surface, speaking to the excess of else. The inability to repeat or see again is all desire, but Law’s treatment suggests something more studious over visceral compulsion. A chest of drawers filled with potting soil reveals a set of deconstructed T-shirts, their elasticated cuffs and collars cut and folded with meditative precision. One is placed alongside a ceramic by Law’s late sister; Law’s study of reconstitution leaves the fragment to take root, its room, here — the expression of care.