From the anthropomorphic urban spaces to the familiar fictional characters, Han Bing’s recent solo exhibition at Antenna Space, Shanghai indeed explores “a labile boundary at best.” The conundrum Han has built into the semantic play of the title articulates those ineffable, complicated, absurd, at times arbitrary, or even paradoxical experiences and projections – emotional and intellectual – the artist has conjured over time.

Unlike Georgia O’Keefe’s New York series spanning the 1920s, in which the artist projected her phantasmagoric impressions of a burgeoning modern metropolis through painting some of the most iconic skyscrapers and monuments of the city. Han Bing’s first encounter with New York and L.A. – the two contrasting urban areas she has resided in the U.S. – took place on the ground level. As depicted in her previous solo exhibitions, the artist focused on the layers and scraps of peeled off posters on the street, adding dollops of paint on newspapers as a kind of forceful if not awkward way of documenting a time through current events, and portraying the textures and patterns that are commonplace to the unruly fabrics of urban sprawls. In essence, all of these have been ways in which Han Bing tried to establish a relationship with these foreign places. This is also perhaps the reason for assigning place names to her paintings, for example, Mott Street (2017), to which the viewer may accord the visual representation with the artist, as much as one’s own experience and emotional projections.

In this sense, it is rare to find a “figurative” painting among Han Bing’s oeuvre. Yet, the head portrait of Peter Parker, a pop culture superhero, is an adroit addition to this exhibition. Although small in dimension, the work nevertheless magnifies Han Bing’s intention for this series of works – to tap into the psyche of American culture. A simple rendition of Peter Parker’s mask suffices to hint at its very iconic purposes. Not only its very iconography embodies the ultimate American spirit, that any individual can be empowered to fight injustice, but the character itself could also be conceived as the artist’s doubleganger. Who, like Parker, is an interface, translating reality into phantom visuality.

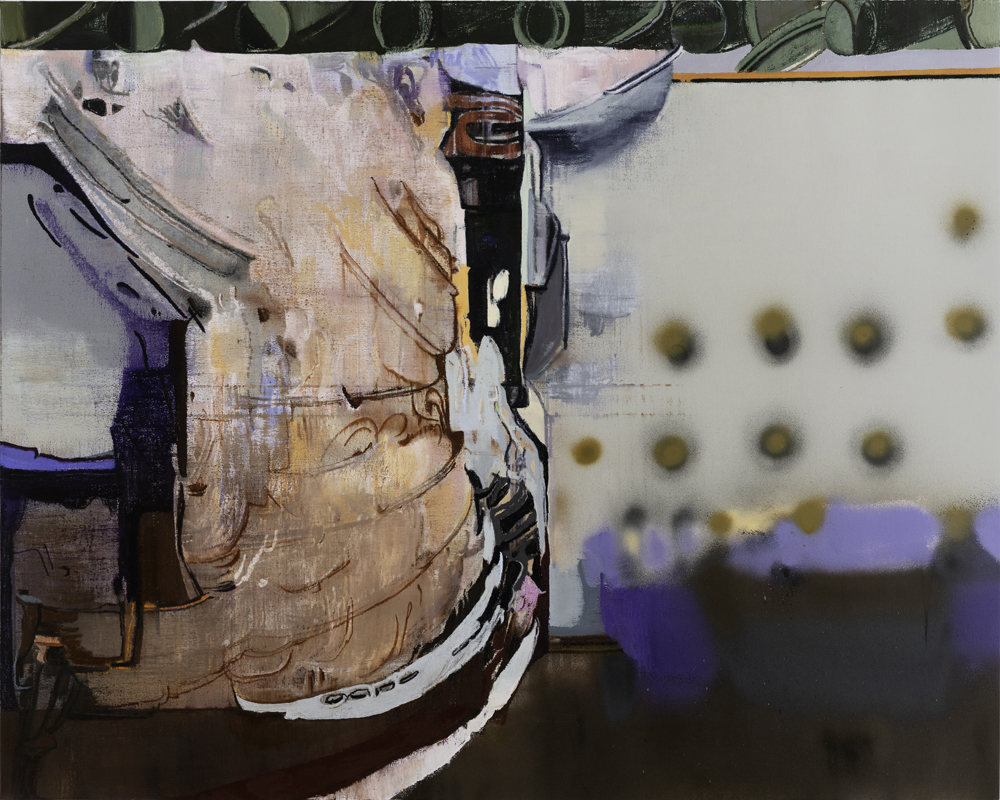

Likewise, many of the works in this exhibition can be traced back to a specific reference in modern American culture, works such as Silver Lining (2019), Angels in America (2019), I am not unaware of my reputation for self-seriousness (2019). At the same time, Han Bing’s tableaus hinder the viewer from making such an immediate visual association. The distinctive layers of color are often nestled with cursive lines and dysmorphic forms, that in some places, unfold into multiple picture planes. Executed in some of the most luscious colors one finds on canvas, the olive green, burgundy, teal, violet, among others, are often set within the same color range that appeals to emotional resonance, be it gloomy, fearful, precarious or hopeful.

To achieve such an ambiguous and compounded emotional response to her images, Han Bing has been adopting the approaches of collage and spray paint in her painting practice. These most iconic approaches of art in modern Americana, the former identifies with the picture generation and the latter with graffiti and street culture, are indeed the perfect registers for Han Bing’s indecipherable and often, uncanny images. The good, the tough and the complex (2019), Peaceful satire (2019), The hedonistic wound (2019) among others, even further removed from any specificity – both with regards to time and place, at the same time, their nearly life-size dimensions draw the viewer into the vertigos of complexity vested in them. These visual tropes, increasingly apparent on the artist’s canvases, shed light on Han Bing’s engagement with the cultures she has dived further into.

It would be too simple to appreciate Han Bing’s paintings under any set of dichotomous notions of this century-old medium – painting – be they figuration versus abstraction, fiction versus reality, natural landscape versus urban environment, or traditional versus virtual. While it is apparent that all inform her paintings of them, they equally attempt to defy the confines of their prescriptions. On each canvas, one finds the artist’s articulation of integrating and amalgamating the native and the foreign, the historical and the present, the classical and pop, the real and the fantastic. Her tableaus hence become the vessels through which Han Bing has channeled these cultural encounters, negotiations, and assimilations. As the artist carries on with her peripatetic experiences in these metropolitan centers, where Rem Koolhaas suggested in Delirious New York that, “Urban spaces are where the real and natural cease to exist,” her mesmerizing images are sights that allow the viewers to revel in fantasies.