Over the last several decades, spiritual themes seem to have been largely missing from contemporary art, replaced by the conceptual, the grandiose, the high-tech, and the monumental. But now a host of exhibitions suggest a new trend toward spiritually minded art and, perhaps, a more spiritually minded world. There’s no denying the fact that we are living during a time of upheaval. In addition to the climate emergency and the current state of geopolitics, mankind is presently facing what may be the most deadly pandemic of the past one hundred years: Covid-19. Indeed, times of woe inspire a search for alternative understandings of present-day reality.

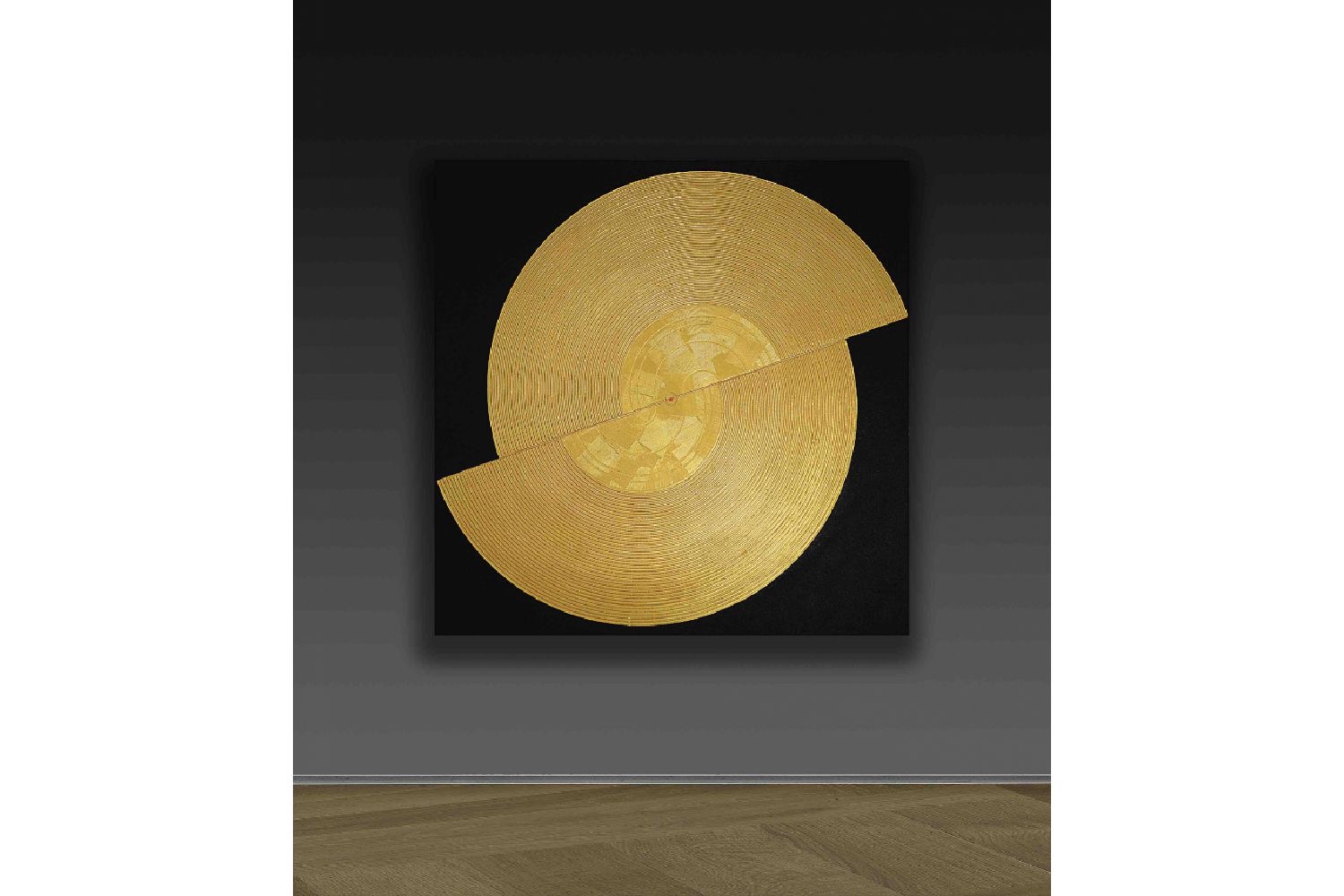

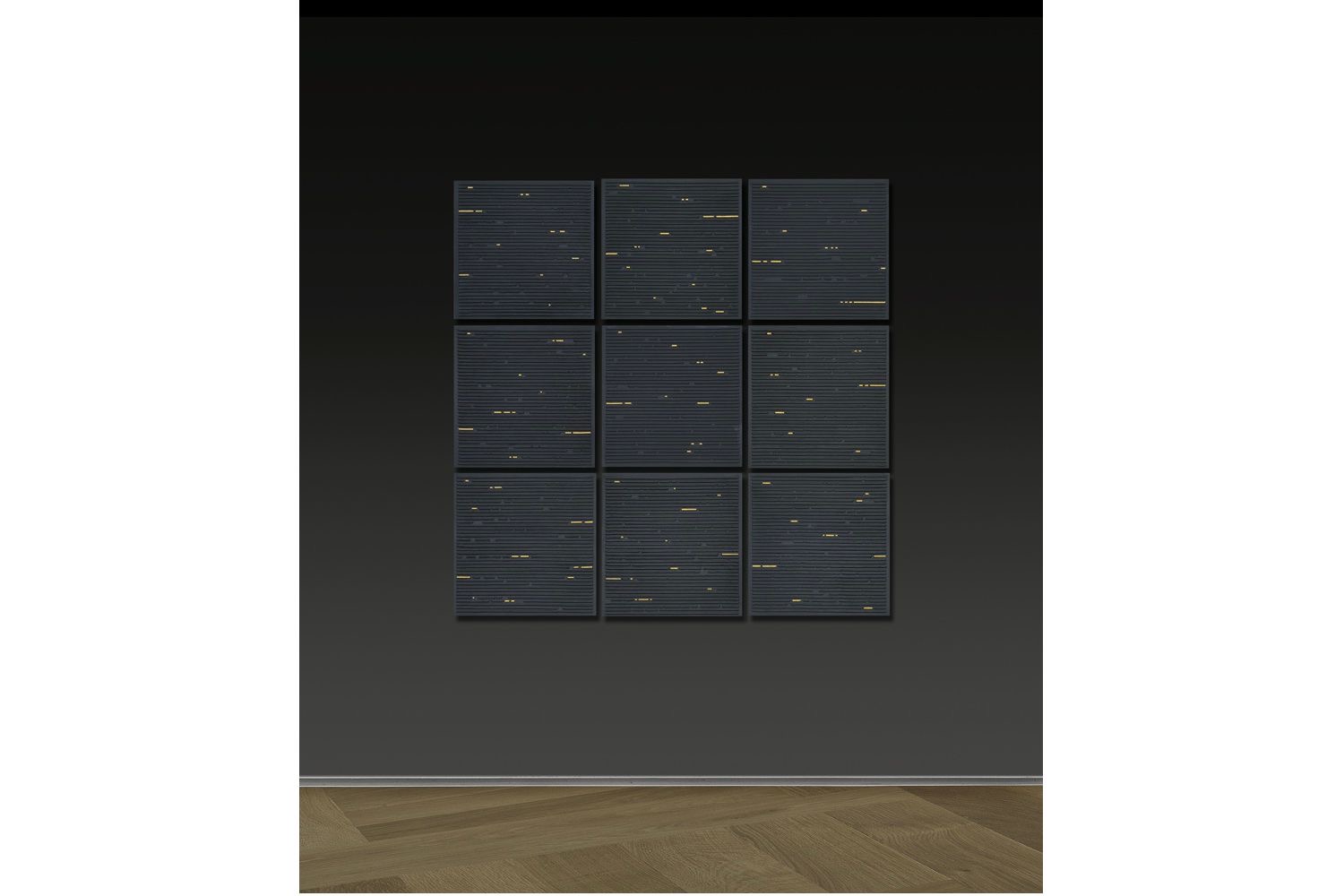

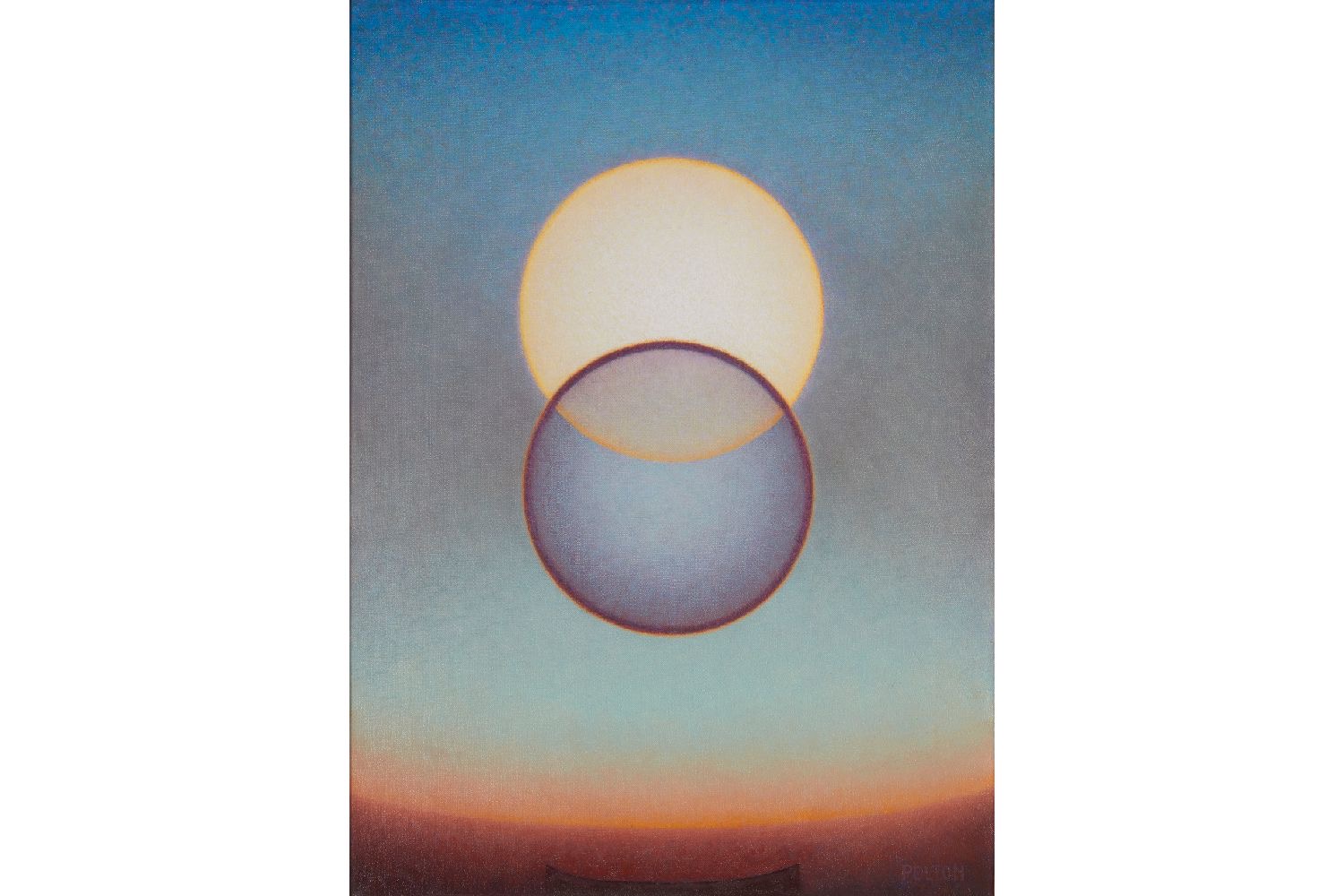

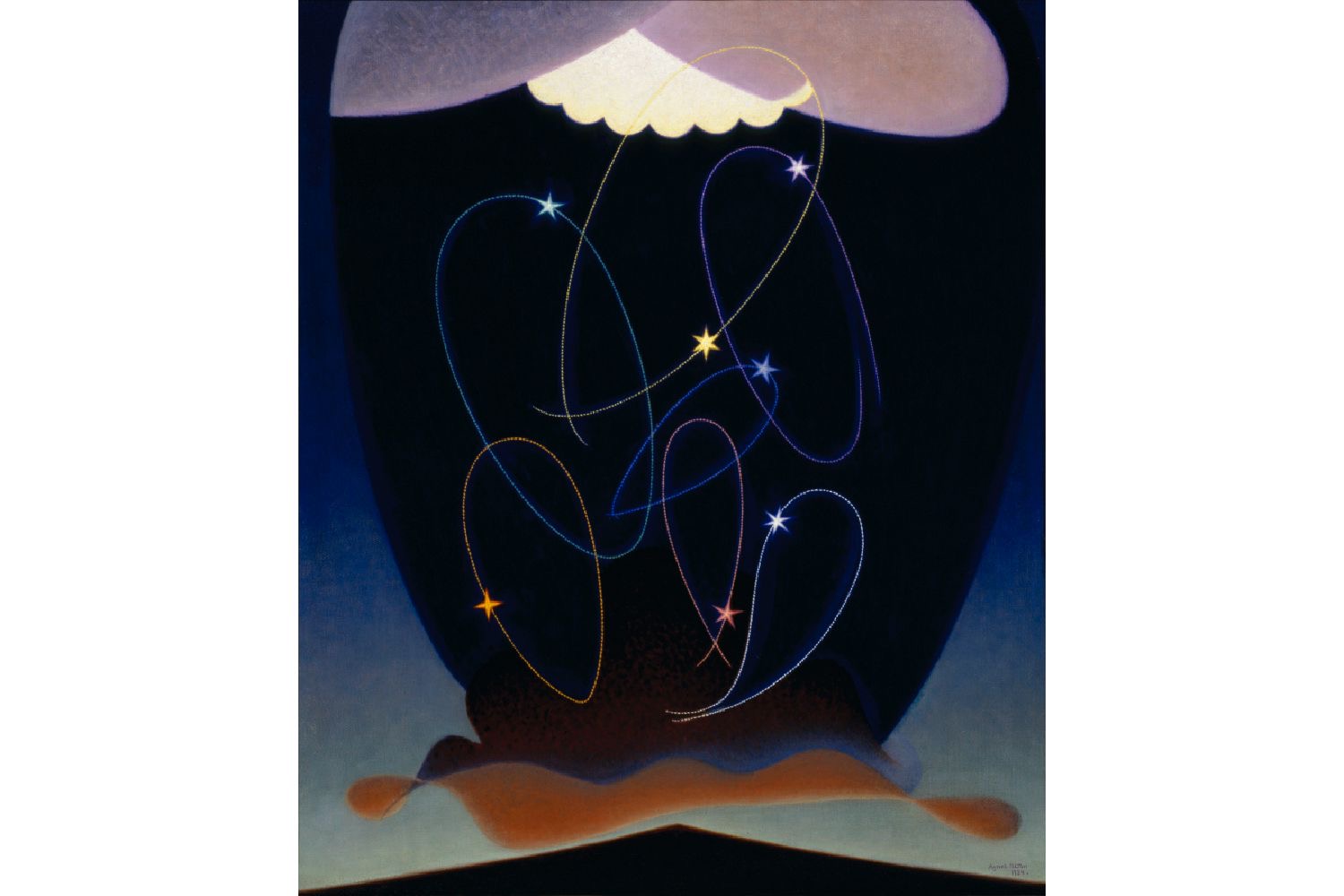

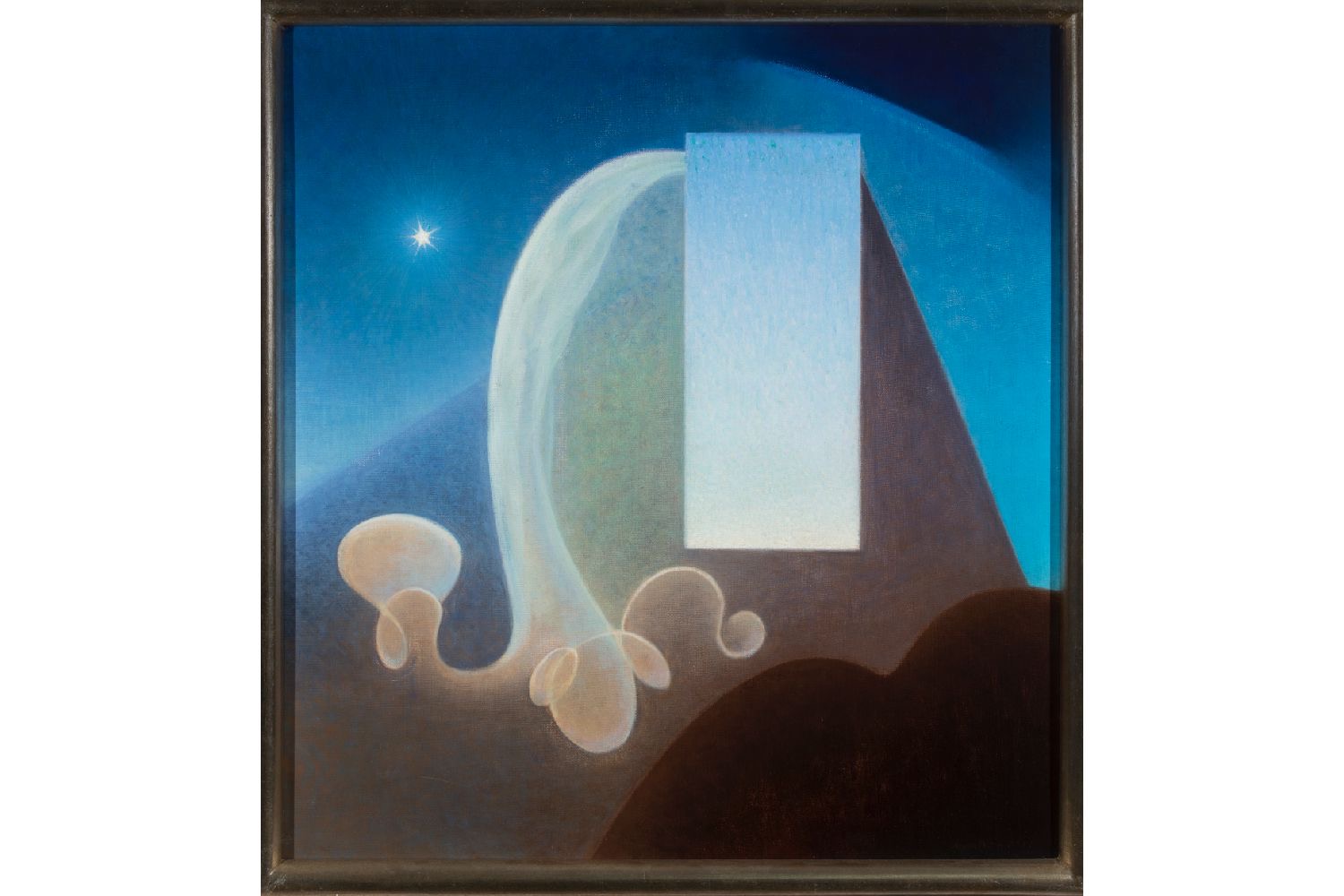

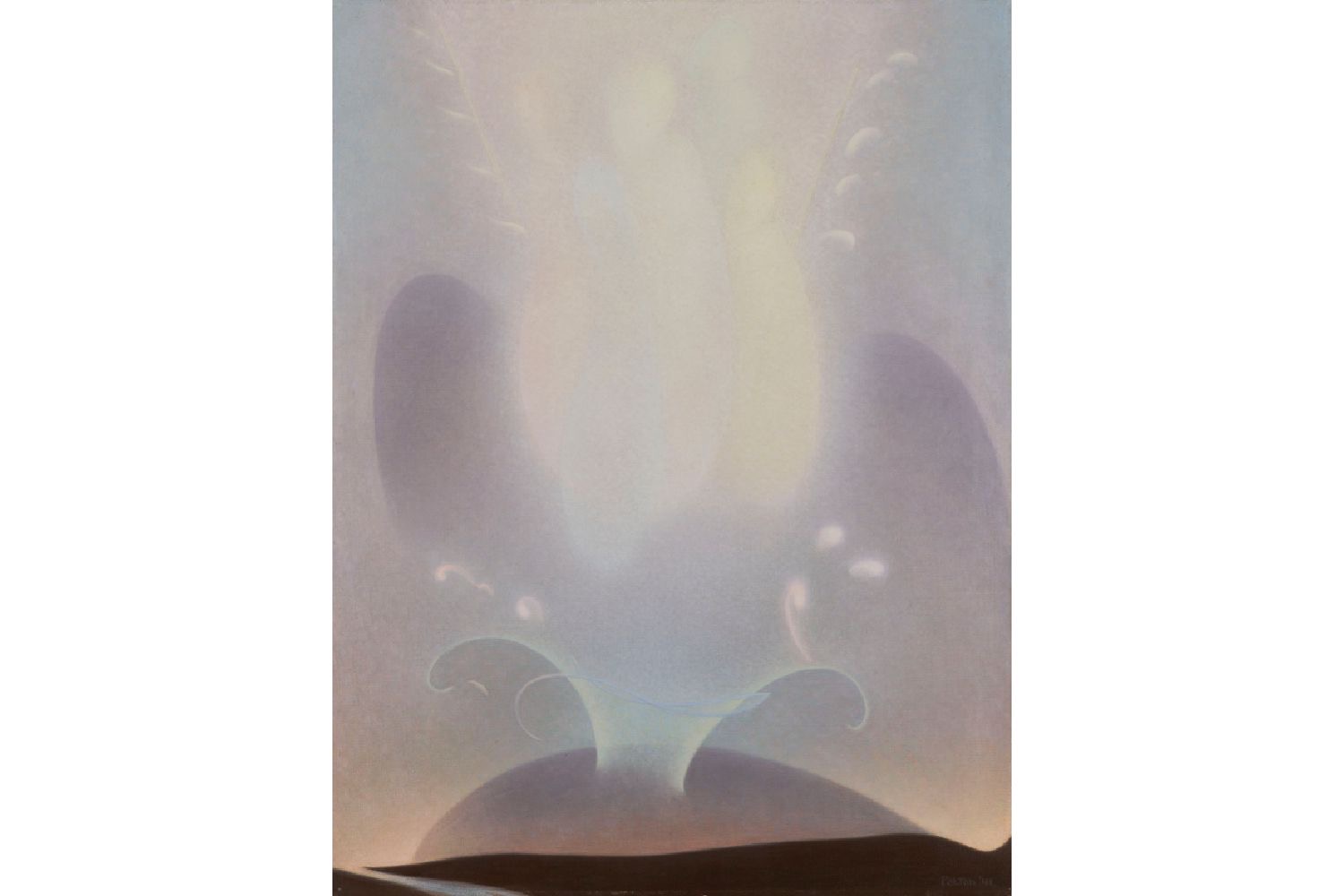

While we are certainly facing a pandemic disease, we are also facing a pandemic of fear. How apt, therefore, that a host of recent exhibitions have looked at how artists increasingly incorporate aspects of spirituality and alternative philosophies in order to better understand the hidden forces that shape our world. The first large-scale revisitation of the spiritual in art was Massimiliano Gioni’s “The Encyclopedic Palace,” held during the 2013 Venice Biennale. This year has already seen several exhibitions dedicated to artists who use their medium to explore the mystical realm. “Gianfranco Zappettini: The Golden Age” at Mazzoleni in London showcases the work of the Italian abstract painter (b. 1939) who co-founded the European Analytic Painting movement in the 1970s. During the 1980s Zappettini was introduced to the Eastern philosophies of Zen, Taoism, and Sufism — philosophies that have guided a quest for metaphysical perfection in his current body of work. Opening this month at the Whitney Museum of American Art is “Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist,” (until 28 June) which traces the work of the late visionary symbolist (1881–1961) who depicted the spiritual reality she experienced during moments of meditation.

Then there’s “on the spiritual matter of art,” which opened at MAXXI, the National Museum of XXI Century Arts in Rome, last October and culminates this month. Curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi, the exhibition features works by an all-star group of artists from around the world, including Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi, Shirin Neshat, Sean Scully, Hassan Khan, Haris Epaminonda, Jimmie Durham, Victor Mann, Abdoulaye Konaté, Tomás Saraceno, Jeremy Shaw, Elisabetta di Maggio, and Remo Salvadori. The exhibition investigates the spiritual through contemporary art as well as the history of ancient Rome. Works by artists from various nationalities and cultures are placed in juxtaposition to seventeen archaeological relics dating back to the Etruscans and Romans. In this sense the show’s scope is ambitious: it traces the spiritual across time and space, attempting to offer some sort of symbiotic understanding of the mystical in art from antiquity to the present.

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer believed art has the possibility to provide knowledge of the world in a way that is more profound than science or everyday experience. As Giovanna Melandri, president of the MAXXI Foundation writes, “I am convinced that the question of our spiritual nature, above and beyond any religious dogma, is a question that urgently needs to be asked of contemporary man.”

The show commences with Matilde Cassani’s Tutto (2019): two fabric curtains placed at the entrance of the exhibition that serve as a metaphor for a place of passage, an entry point into this otherworldly mix of objects from disparate time periods. The work was first shown as part of a performance during Manifesta 12 in Palermo. After walking through the portal we arrive in a room filled with various artworks, including Enzo Cucchi’s Idoli E Scopritori del Fuoco (Idols and Founders of Fire) (2010–14), a series of bronze sculptures installed on slender columns depicting figures that recall those of the ancient world: half-men, half-gods, wizards, vestals, symbols, icons.

Not far away is South Korean artist Kimsooja’s Mandala (2003), in which she reverts back to the form of the Buddhist mandala to explore ideas of the sacred and profane. A jukebox speaker within the work invokes Tibetan, Islamic, and Gregorian chants. Then there’s Abdoulaye Konaté’s serene, large-scale fabric work titled Ocean, Mother and Life (2015), which depicts a vibrant underwater scene filled with brightly colored and evocatively patterned fish. It’s an homage to water, a vital natural element that was sometimes hard for the artist to obtain when growing up in Mali.

These works appear amid numerous ancient votives and sculptures, such as a leontocephaline statue, the deity of Roman Mithraism, dating to the second century AD. There are also several sculptural crowns, such as the crown offered to Fortuna Primigenia, the deity of the sanctuary of Praeneste (now Palestrina); a pair of ancient hands in bronze; a gorgon; and ancient gemstones, some with carnelian stone intaglio illustrating scenes from antiquity.

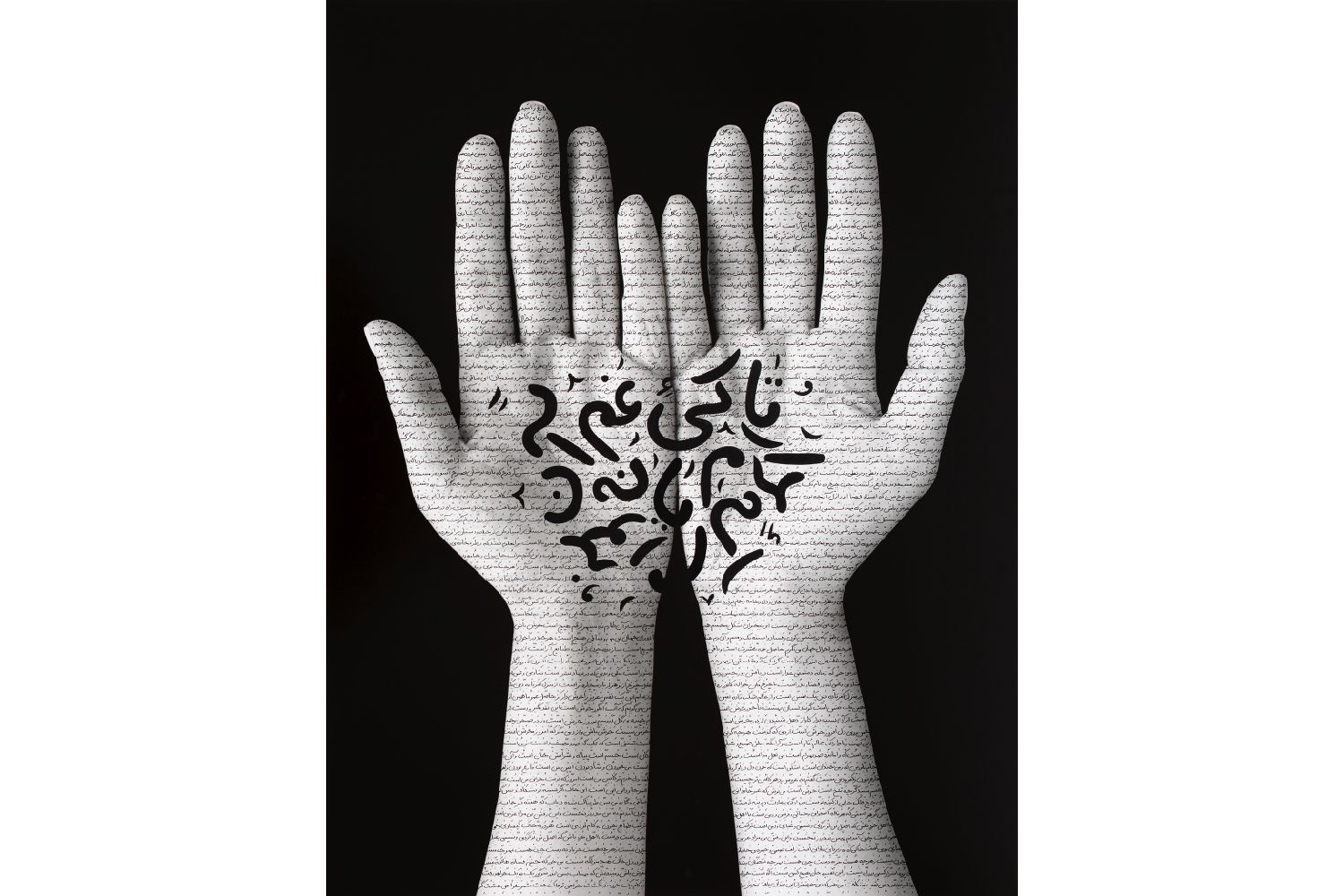

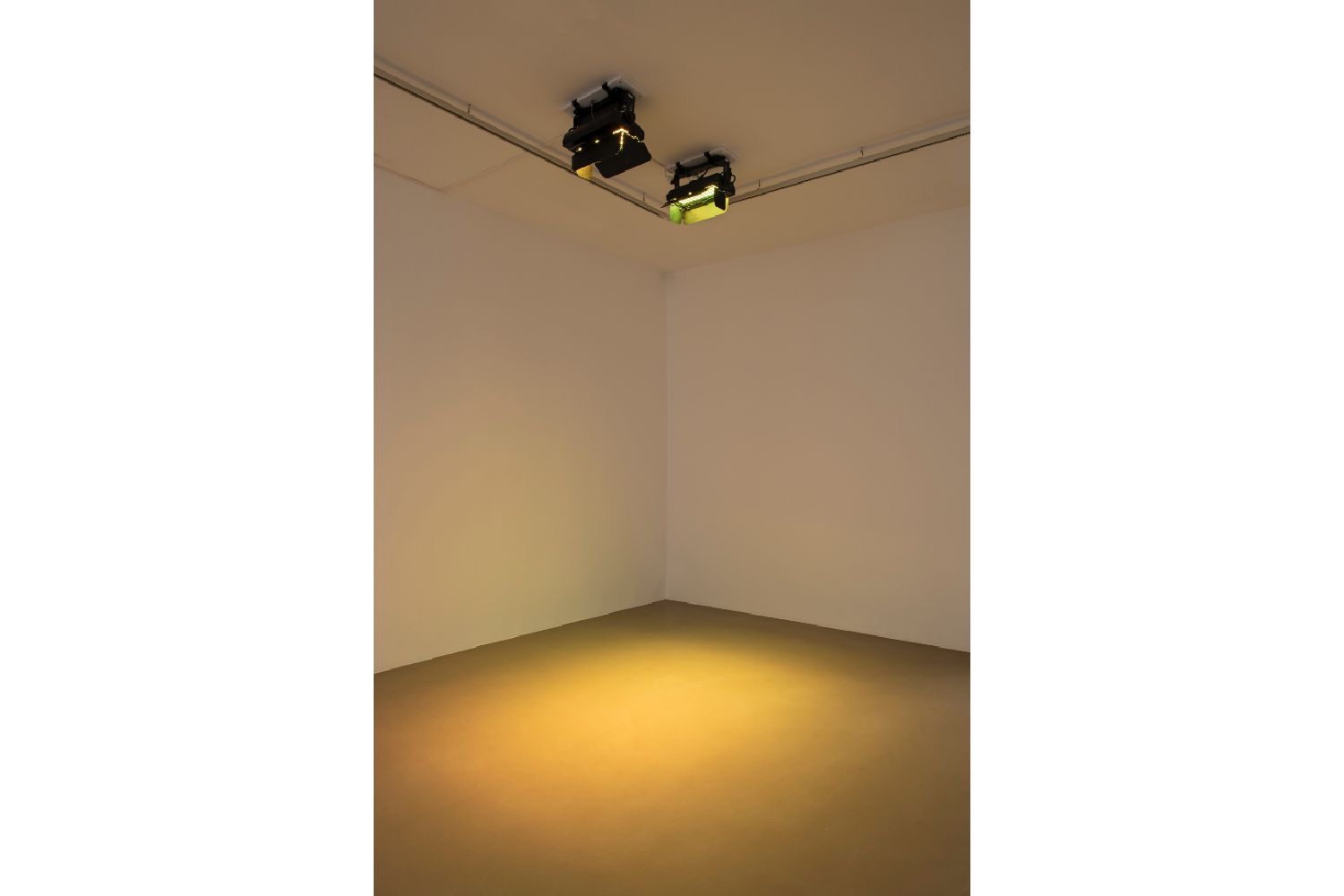

On a nearby wall are works from Shirin Neshat’s photographic series “Offerings” (2019). These images of henna-decorated hands recall her earlier series “Women of Allah” (1993–97), famous for its reflection on the complex nature of Islamic culture and its relationship to female identity. There is almost always an element of prayer in Neshat’s work, which expresses itself like a revelation. A few steps away are the throbbing techno sounds of Hassan Khan’s Live Ammunition! (2015), a four-channel sound installation that uses video, sound, and performance to pose existential questions. It creates a multisensory experience for the spectator — a kind of initiation or suspended space in which viewers temporarily pause before entering or exiting the show.

Yoko Ono’s participatory Add Color (Refugee Boat) (1960–2019) concludes the exhibition. Inside a room is a boat and a supply of paint with which visitors may add color, paintings, and messages to the wall, floor, and boat. The work explores universal concepts of freedom, hope, love, and peace, becoming a ritual in itself that offers a moment of collective contemplation.

“On the spiritual matter of art” reacquaints us with the intangible recesses that encircle our daily existence. As these artists so cleverly reveal, art is a vehicle to better grasp invisible realms that science still cannot. As Andrea Carandini, an Italian professor of archaeology specializing in ancient Rome, so rightly states in the catalogue: “We are made of a dark and burning energy and of a luminous and gelid thought.”