Maybe it’s the ebbtide of articles taking stock of the decade—the best-ofs, the what-did-it-all-means, the where-were-you-whens of last month—which makes us (I know you’re with me) want to tell a story about art in Los Angeles in the 2010s as the story of the Vanity. Oh, it writes itself. We open on Asha Schechter: it’s 2011, the renegade spirit that fueled the Chinatown art scene of the previous decade has been all but extinguished by the consolidated power of Culver City, and as our budding artist surveys this bleak landscape his attention turns to his own Miracle Mile apartment, down an interior hallway, to one of those charming features common to 1930s domestic architecture in LA, a built-in vanity closet, and he realizes that this nook slathered in countless coats of paint will be an exhibition space. In the shows that follow—Patricia L. Boyd, Olga Balema, Ian Cheng, Alisa Baremboym— flimsy, synthetic, and fissiparous materiality and imagery play against the intimacy of the alcove and the communing out in the living room. In 2014 the Vanity moves into a supply closet at 356 Mission Road, an exhibition and performance venue in a disused piano warehouse in Boyle Heights, which for five years offers the city’s most consistently compelling cultural programming. While the mainstage features Sturtevant or Michael Clark, the cramped quarters of the Vanity East presents an eccentric counterpoint—an exhibition of holograms, a congested memorial to the street fashion photographer Bill Cunningham. Suddenly, everyone, it seems, wants to be by the Vanity: more and more galleries open in this industrial zone called the Flats, and then just quickly begin to shutter or disperse in the face of a protest movement that sees the galleries as the spearhead of gentrification. It’s a story that eschews easy answers. A story of power and the place of art. Of tiny spaces in a sprawling city. Of humble beginnings, dizzying heights and finally the pitchforks and torches.

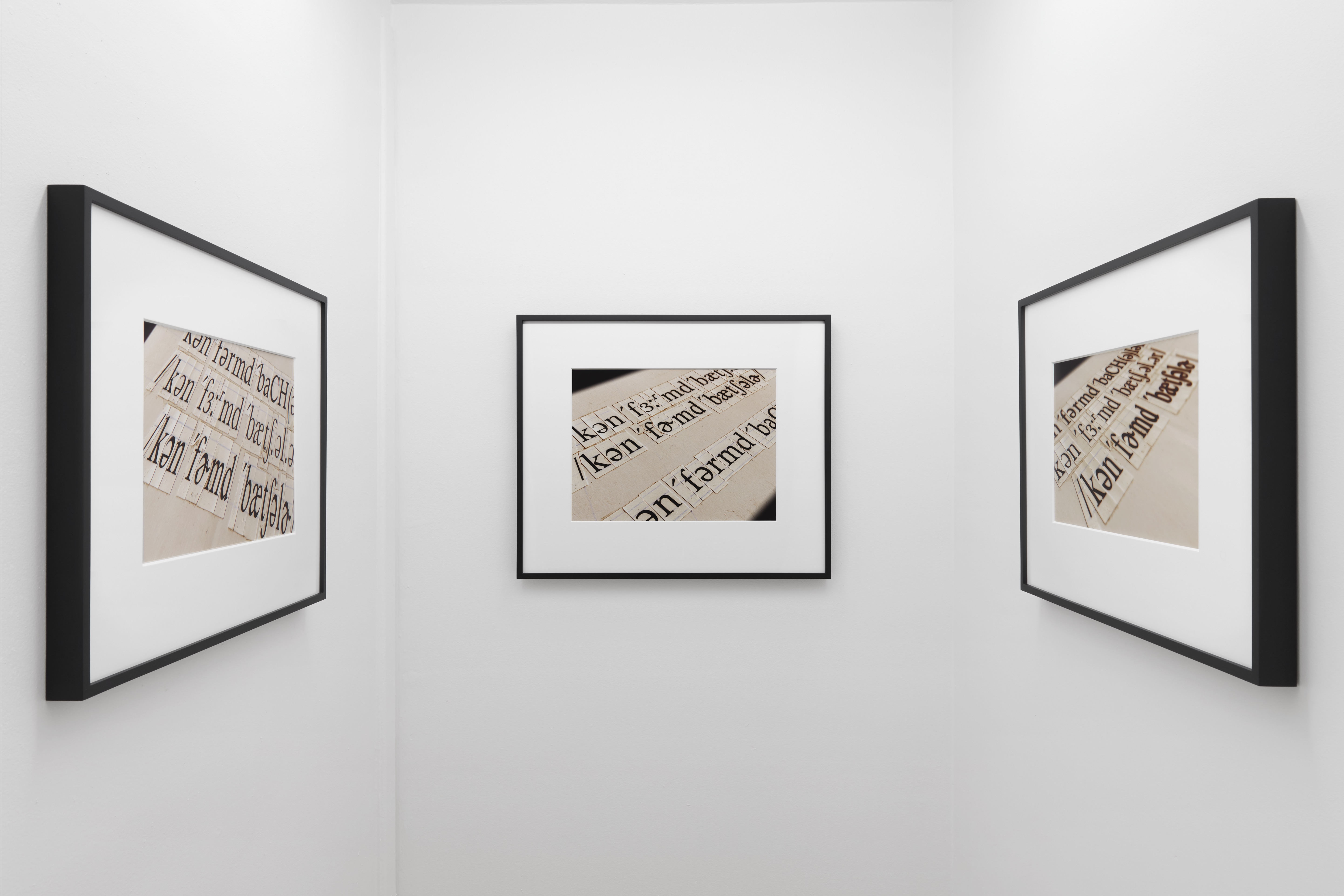

Having already shown itself adaptable to sequels (I never made it up to the Vanity Bakersfield myself, but some say it was the best of the bunch), Schechter’s little gallery managed to squeeze in one more appearance at decade’s end. He’d been talking with Larry Johnson about showing in the broom closet back in 2016, a plan brought to belated fruition with a reconstruction of the Vanity East as part of a two-man show at Jenny’s. The artists share some interests—graphic design, cartoons, the transubstantiation of media—and like a strabismic flashback, the resurrected Vanity made a peculiarly apt context to find Johnson, an artist closely associated with Los Angeles of the 90s and early 2000s, who has sometimes made the city his subject, and whom we haven’t seen much of since his retrospective at the Hammer in 2009. Johnson took his longstanding focus on encoding and decoding—of media, desire, and gay signification—into Schechter’s closet, with a trio of photographs depicting text laid out in the old paste-up method of preparing pages for publication, spelling, in three different lexicographical pronunciation systems, the phrase confirmed bachelor (Untitled (Image #1-3), 2019). Have your pick: whichever system you prefer to un-translate, to turn orthography into utterance. Even if we have no need of a definition, the question is how this antique euphemism sounds now, when apparently nothing is hidden, and how much our simplistic preoccupations with history leave unsaid.

On the wall opposite the Vanity: a cartoon mirror of concealment and disclosure in a pair of framed prints hung cockeyed—flat fields of light brown, interrupted in one case by a jagged crack revealing illustrational red brick, and in the other by a cute polka dot patch (Untitled (Straight to Hell, Details), 2019). The wall beneath was covered entirely in a toile wallpaper entitled Flaming Big Top (for Charles Nelson Reilly), 2015. The dedicatee, who has a very informative Wikipedia page, was a Broadway actor and fixture of 60s and 70s television, where “he gave signals on-camera of a campy persona” and later “revealed his homosexuality in his theatrical one-man show Save It for the Stage: The Life of Reilly.” Also on his resume: at thirteen he survived the Hartford circus fire of 1944, “one of the worst fire disasters in American history,” commemorated in the pattern’s gauzy depictions of elephants and balloons and old-timey firetrucks interspersed with the images of the Hartford fire that come up when you Google it. The archaizing decorative motif speaks to the domestication of queerness—quaint circus spectacle and unthreatening little blaze admitted into the fabled bourgeois interior.

If, as we’ve read in Walter Benjamin and his numerous disciples, the appurtenances of the domestic retreat both reflected and forged nineteenth-century bourgeois subjectivity, Schechter seizes on the difficulty of updating this relationship between objects and interiority today, when consumer commodities are more numerous, vociferous, and yet harder to hear as shibboleths. He scrutinizes taste, banality, and product design, the ways that objects and subjectivity both glint across the surfaces of screens. Here he presented a pair eight-foot-tall vinyl stickers of drinking straws, hyperreal 3D models made flat as flat can (Paper Straw (Yippee); Ecostraw (Elephant), both 2019). They are mundane curios of (literally) heightened specificity, and their titles let us know that these two are kosher in the context of the California plastic straw ban, a half measure that has nonetheless been a flashpoint in the culture wars. The repeating patterns (“yippee” and an agreeable cartoon elephant) sound a whimsical echo of emptiness, like an instrument plucked from a vanitas.