Saturation occurs once again, the city drenched in expos, events, and itinerant first-timers. Given the slight period in which to encounter the vast array on offer, I’ll start with the broad rubric of time itself. While some things deteriorate, others resist time’s effects by way of relationality, reconciliation, or the favoring of capricious notions of community. Such is the modus for Palais de Tokyo’s “Future, Former, Fugitive,” which pools together forty-four intergenerational artists and collectives as a marker of “a French scene” — nearly ten years since its similarly monumental show “Dynasty.” In Oliver Cadiot’s 1993 novel Future, Former, Fugitive, he sets an inventory of tactics in the event of exile. In this same story, Cadiot invents Robinson, a vehicular character through which sensations and perceptions are processed at accelerated rates. Evolving from Cadiot’s early cut-up poetry, Robinson’s narrative “I” becomes an empty site for the heterogeneous language of the contemporary world, provoking a hallucinatory proliferation of linguistic excess. Though a marker of a scene (one of many we shall see), Palais de Tokyo’s approach is in a similar vein, reconstituting a place for games of language, excess, and doubt.

Contagion seeps through even the most solitary expressions: Nils Alix-Tabeling’s wooden reptilian hybrids queer mythological narratives to confront the apocalyptic present in sculptures featuring, among many crossbreeds, a two-faced arachnid vase and a nimble throne adorned with carved dragonfly wings, a lolling cock, and clawing hand. Corentin Grossmann’s crayon, pastel, and graphite drawings perk the attention with their woozy vistas, untroubled nudes, and rolling landscapes. The marzipan-smooth scenery is populated with de-stoned avocados, hovering planets, botanical phalluses ejaculating foamy toothpaste, and sushi traveling downstream while yellow tang fish float above. Renaud Jerez presents burlesque characters inspired in part by Orwell’s 1984 and the recurring sex workers throughout Otto Dix’s oeuvre. Industrial pipes create interconnected exoskeletons as a figure guards a mirrored tomb; the room is bookended by two canvases featuring a dissolving grim-reaper and a bewitched ode to John Everett Millais’s Ophelia.

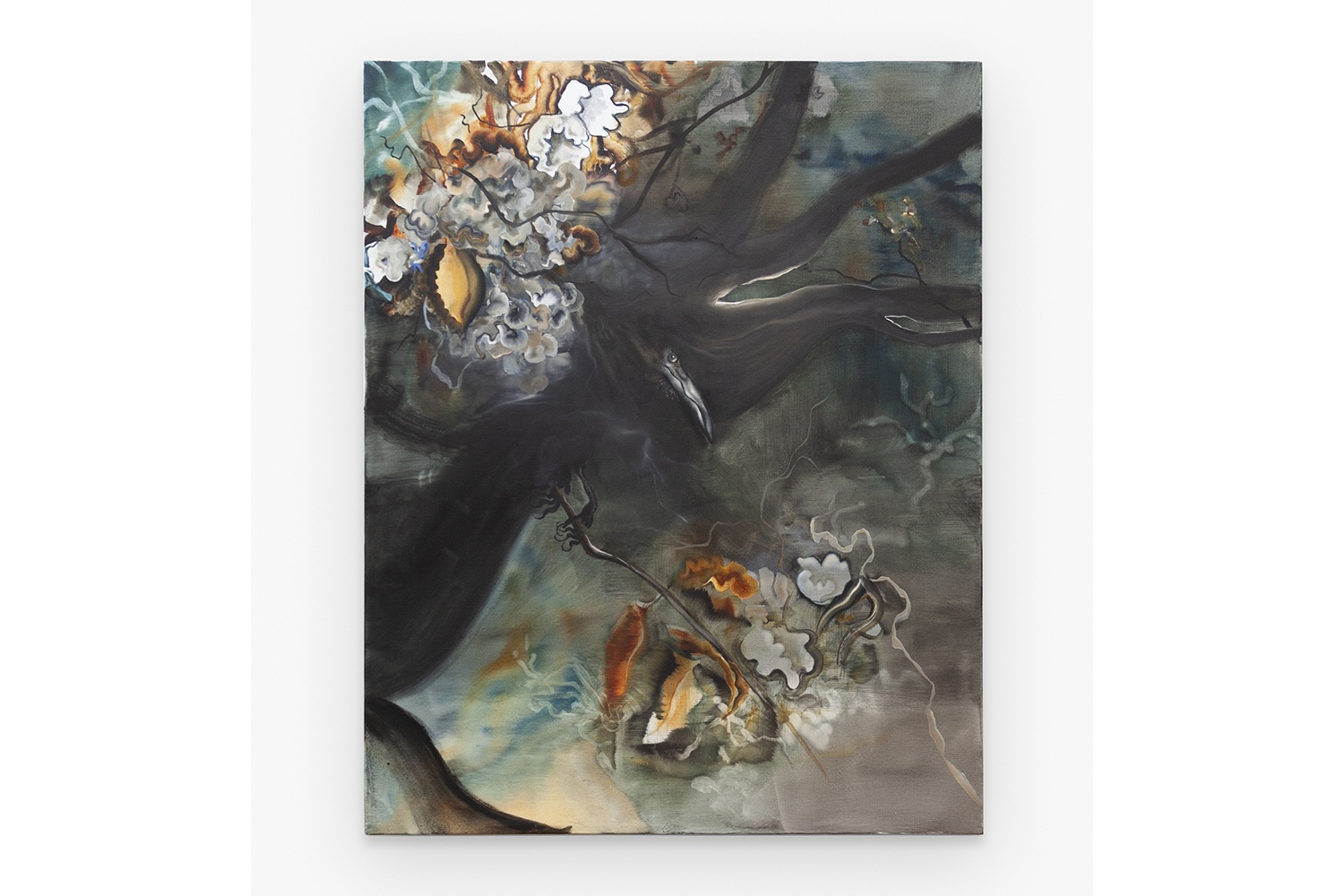

To the volcanic center of it all and with no thematic spine in mind, I stumble into booths weeping in white light under the Grand Palais, gunning for more fine flakes of excess. In a queasy head rush, best to start with decapitation. Picture: slurry of verdant greens; picture: an abattoir-picnic of Cicero’s rotting head strung to a tree; picture: eyes, whole abscesses, pustular and galactic in sparkling putrefaction; picture: a snake twirling into the fleshy envelope, feasting on its contents inside out. Kye Christensen-Knowles’s The Silence of Cicero (2019), on show with LOMEX at this year’s Lafayette Sector in FIAC, was a welcome contusion in the system.

Thirsty for more hot proclivities, masochistic practice, or profuse materiality I reach Galerie Joseph Tang’s presentation of work by Daiga Grantina: magnificent quenelles rolled into craquelure-like hardened caramel in tones of toffee, peach, and blood orange, the latter’s lower curve dipped in a smattering of feathers. A central assemblage composed of hulking shards of foam and silicone in licorice-red and rosewater reads disarticulated nest, while the discrete wall clusters are neatly gelled, feeling like more assertive endnotes for a faintly folkloric and rich plastic lexicon.

Making up a small portion of works at Anton Kern Gallery are paintings by David Byrd (1926–2013), who formerly worked for thirty years in the Veterans Administration facility in Montrose, New York, before retiring to paint. In his bleached pastel palette, figures, landscapes, and at times the softening unity of the two, are sensitive renderings of his time spent working in the VA where the most distressing forces are often invisible. In Man In Bed (1973) a figure appears awash in liquid flurries of cotton, the body scarcely distinct from the mattress. In another, Byrd traces the medicalized mind in solitary extremis via a male figure holding only a string.

Other stroboscopic notices came in quick succession: a painting of one luminescent citron cocktail served like a lambent candle by Dike Blair at Karma; equally radiant were the extreme cropped talismans of Alexandra Noel’s paintings at Freedman Fitzpatrick, including an injured horse, and retro American houses — their roofs illuminated like razor blades. For a bigger splash I ogled Louisa Gagliardi’s silky paintings of metallic phantasms and oily reflections at David Radziszewski: black symbolist felines, hollow bodies, and golden globes where faces slip and slide onto other bodies, onto cherries, or bust into pure steam.

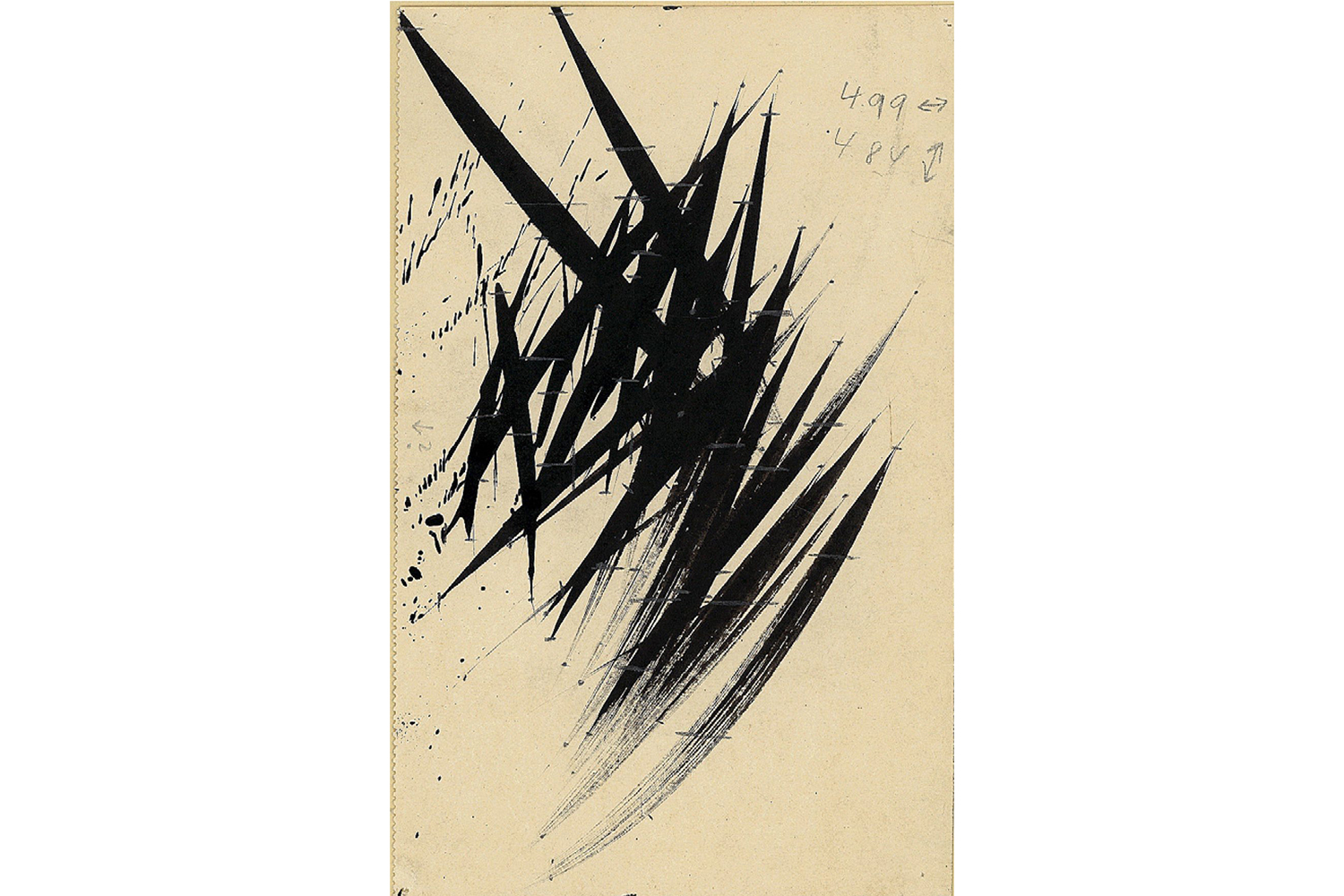

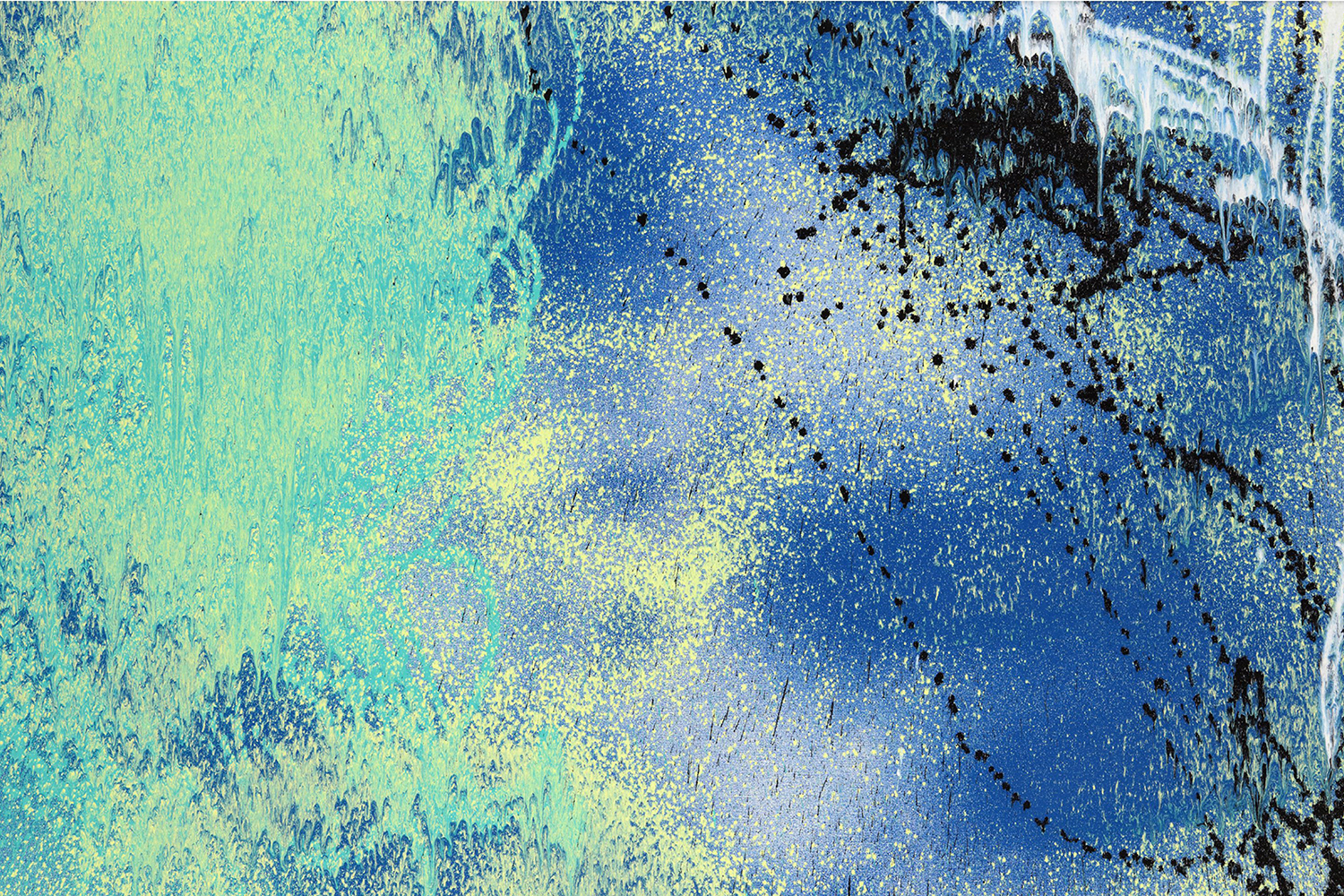

Pivoting from diaphanous cacophony to infatuated authorial mark, I visit Hans Hartung. At Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, his gestural and abstract style, so promiscuous with scrawl, is more radiant and scathing than I anticipated. Almost libidinal with tricks of something machinic in his handling of sprays and aerosols, Hartung’s paintings, pastels, and lithographs are hatch marked close to oblivion, swirled and lyrically erased in great unctuous waves. His swathes of black, bronze, and navy evoke the graphic fluster of ruffled plumage. Representations of hallucinogenic wind, a cockatoo’s shock, or bizarre weaponry: Hartung could suggest them all.

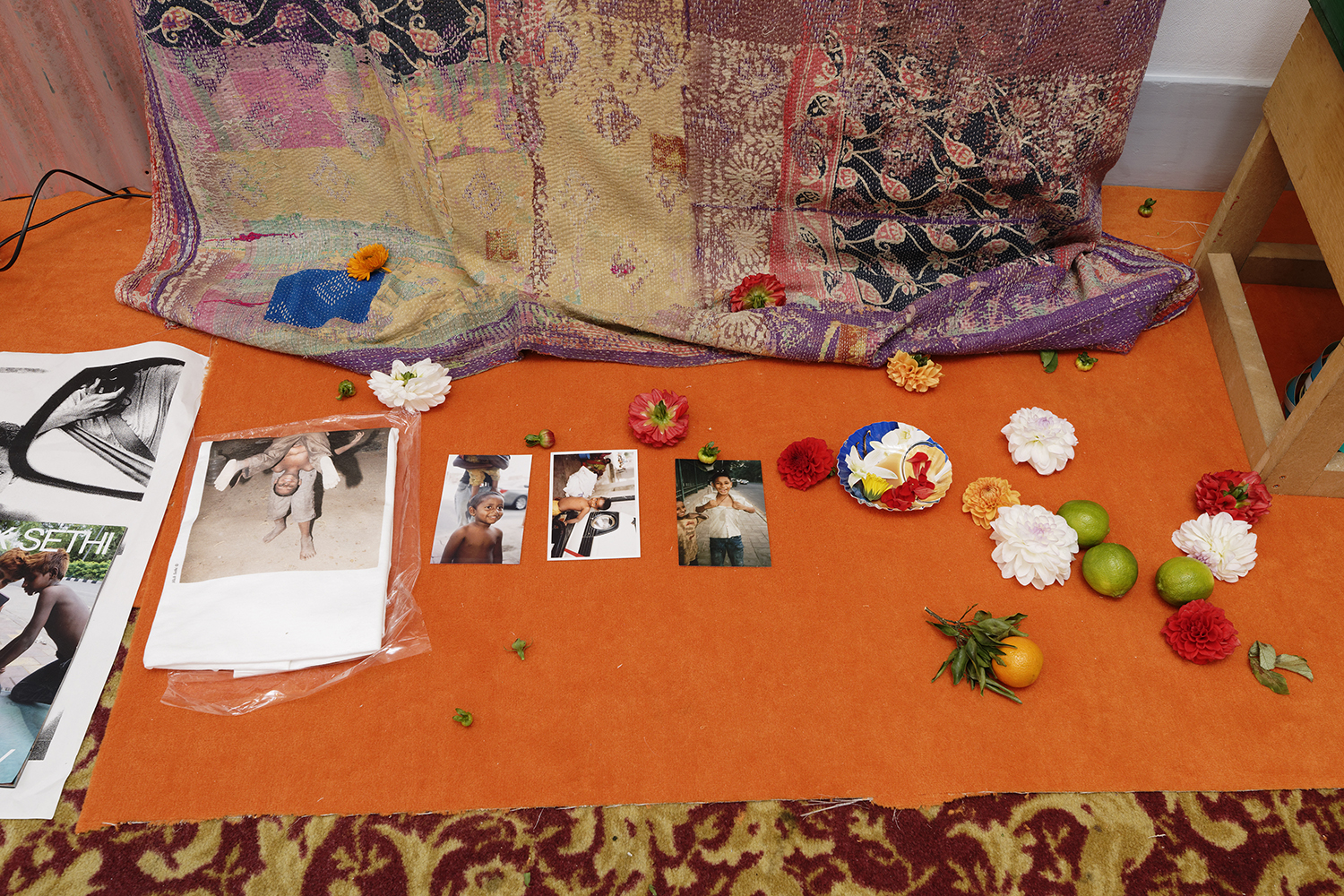

More transient and site-specific was the program for the inaugural Salon de Normandy, housed at Le Grand Hotel de Normandie in the shadow of the Louvre. Curated by multidisciplinary collective The Community, the project is a playful destabilizing satire on the conservative nineteenth-century salon. Given its context, participating galleries and nomadic collectives embed display within setting, leaving objects, commodities, and atmospheric installations interpenetrating hotel facilities. Orgiastic and bacterial in scope, the hotel summons a portalist methodology with each room a peephole. However, precarious form and rudimentary application is its connective tissue, clear in Nick Sethi’s live, site-specific ode to India; Alison Lloyd’s introspective sequence of photographic self-documentation; or Michael Iveson’s manipulation of space through painted bubble-wrap vestibules.

Of less wild and more discrete fashion continues Paris Internationale. Enjoyments include Autumn Ramsey’s interspecies bacchanalia at Crèvecœur, including an eagle with overinflated talons and a runaway satyr. Similarly, silhouettes of smooching heads by Robert Brambora at Sans titre show trans-species relations both animal and botanical; or Koppe Astner’s presentation of New Realist works by the late Miguel Cardenas, displaying psychedelic sentient cacti razed like modernist sculptural icons. At Paris Internationale, the Performance Agency’s live TV studio, orchestrating events, tours, talks, and performance, is a dizzying feat in itself.

At Sultana, botanical bodies sit behind glass cabinets dripping in condensation for Jesse Darling’s “Selva Oscura.” In partial reference to Dante’s dark forest, the plants are desynchronized from seasonal time, stripped from the period of dormancy for further root entanglement. Bookbinders and toilet brushes adorn a forest of crutches, the binder of elaborate ideas become undone. I capture Louis Fratino’s new ceramics and sculptures at Antoine Levi, his intimate paintings rendered in three dimensions. I crop them further at a forearm’s shelter or a twisting embrace, inventing their subliminal passion and pulse.

For calm, I stop by “Speed of Life” by Peter Hujar at Jeu de Paume. Consistent documenter of the downtown New York avant-garde, Hujar recorded a multitude of queer subjects including Candy Darling and Quentin Crisp. “Speed of Life” is also sheltered, lonely, and gentle. Hujar crops a leg to linger on the veins touring down the fundamental foundation of the foot. In others: a lone road is made suede by rain, its surface supple with the pressure of petrichor; Skippy the python creates curlicues in a labyrinth atop a varnished chair; lipping the wind, the Hudson river is frozen as a sheet of slate; Stephen Varble sports Christmas-tree netting, festooned with faux dollar bills. Pausing for the act of looking itself, I’ll close this heady walkthrough of the many constructions of value.