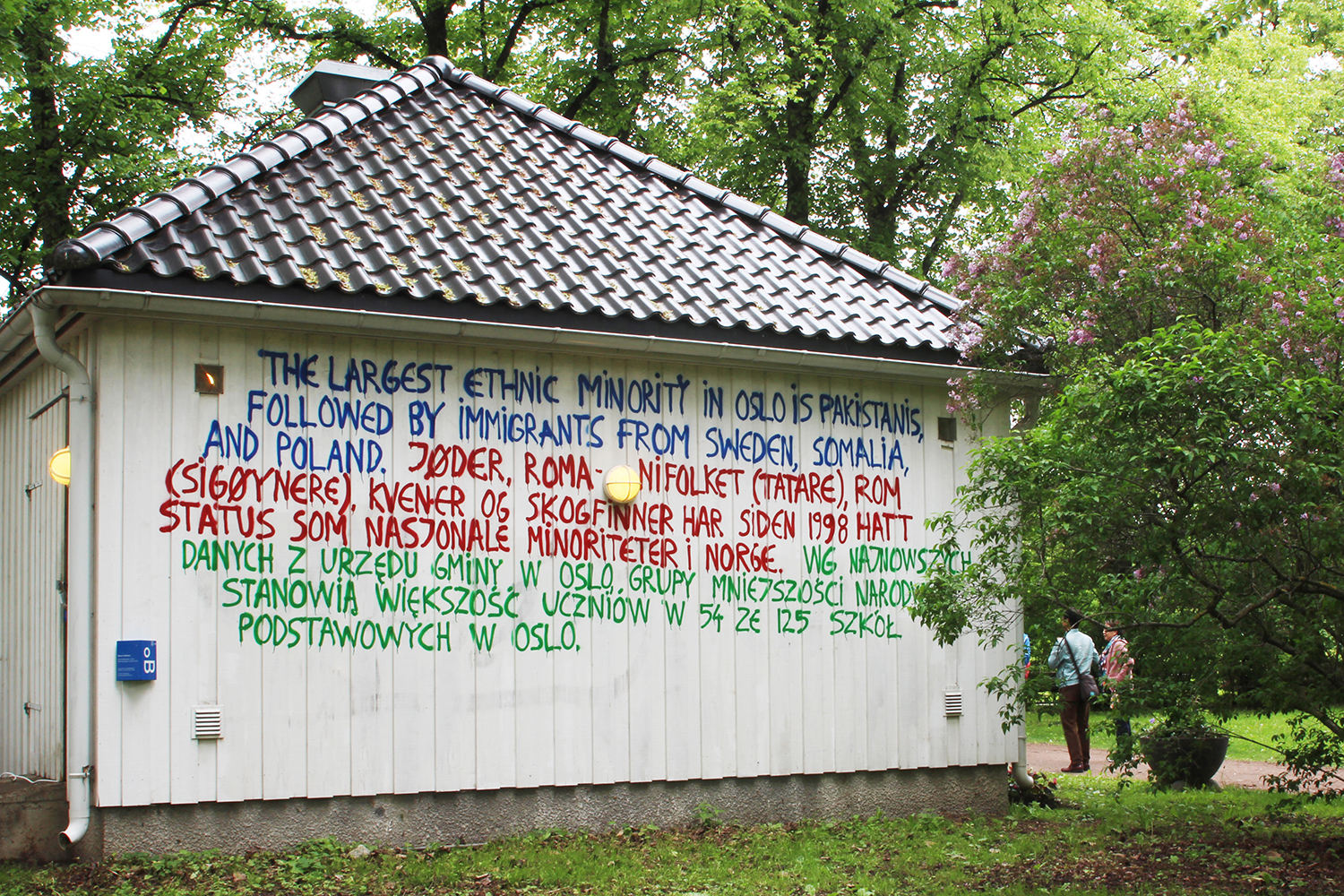

The Venice Biennale opened in the same week as the first edition of the OsloBiennalen. But while the former will be closing within a few weeks, the latter, dubbed “the anti-Venice” by one critic, will remain open for another four and a half years. This is the opportunity — and also the dilemma — that curators Per Gunnar Eeg-Tverbaak and Eva González-Sancho Bodero have created for themselves. To understand the project in its entirety, one should probably consider it along four coordinates: site, duration, artwork, and audience. The show covers the whole expanse of the city of Oslo, where most artworks are installed in public sites — a few in the city center, but some quite far off the grid. Yet the biggest challenge has to do with the timespan and the curators’ decision to keep things open-ended — to not focus on a specific result. This has required everyone involved to rethink the fundamentals of such an endeavor, affecting not only the institution and the invited artists but also the show’s audience — the largest part of it being the people of Oslo, who are also the project’s main funder.

The city of Oslo has set aside a substantial amount of money for the project, not from its Ministry of Culture but from infrastructure development funds. This may have inspired the trio of artist Jan Freuchen, architect Jonas Høgil Major, and writer Sigurd Tenningen to include a large concrete sewage pipe as part of their sculpture pavilion close to Økern Senter, on the fringes of Oslo. The empty plot of land, dominated by traffic on intersecting highways and train lines, commercial buildings and building sites, provides a surprising setting to display sculptures from the collection of the city of Oslo, among others a life-size bronze cast of an ancient Greek sculpture of a wild boar; a huge concrete snail from a public playground, with a bright orange, nearly psychedelic shell; and a contemporary sculpture by Knut Henrik Henriksen, based on architectural elements of the town hall of Bergen, the country’s second largest city. Over time their project will grow and may cover the whole plot by the end of the show.

But how will works change over five years? And how does one involve viewers, locals and visitors, over such a long period? Certainly there are precedents, not least Skulptur Projekte Münster, that could suggest answers. But the curators want to find their own. In an initial two-and-a-half-year research phase they decided on a five-year program without a distinct plan — a premeditated jump into the void as a fundamental challenge not only to existing structures and conventions of the art world, but also the methodologies of public art and artists.

Carole Douillard responded with her performance The Viewers (2019), which consists of a group of performers seemingly doing nothing for a duration of two hours. Standing together in silence, a mixed group of people appear to hold a vigil or a demonstration, transformed by their solemn presence into a temporary everyday monument of magnetic intensity, an image of solidarity. I saw the piece in front of the Y-Blokka, the disused y-shaped government building, considered a modernist landmark, that still bears traces of the terrorist bomb attack, in Oslo and on the island of Utoya in 2011, that left sixty-nine dead and hundreds injured. Viewing the work, I am convinced it speaks to the difficult business of loss and memory. Meanwhile, an old lady shuffles by and, after briefly registering the presence of the group, mutters to herself: “Must be the climate.” The interruption of my thinking is most welcome; it reminds me that the work is a manifestation of neither. It stands for itself, and changes with every viewer in every one of its twelve locations.

Still, the intense public debate about keeping or demolishing the Y-Blokka, and the ways of remembering a devastating terrorist attack, inform several works in the show, thereby creating a strong thematic undercurrent. Katja Høst presented a black-and-white photo series on revolving postcard stands, intending for the works to be taken away and mailed to friends. In her photographs she explores the formal language of the heavy concrete building, designed by Erling Viksjø and featuring figurative decorations by Carl Nesjar and Pablo Picasso. By celebrating its formal, somewhat obsolete beauty, typical for the early era of social democratic reforms, Høst’s photos also trace the unlikely layering of memories associated with them, from the idea of the welfare state, which speaks of the country’s humble beginnings and current riches, to its current art-historical and cultural significance — including the traces of the atrocious attack on liberal Norwegian society.

However, in this exhibition, the national trauma is most precisely reflected in a new film by Jonas Dahlberg, which reveals the artistic and personal processes that lead him to submit the proposal for the memorial he designed for the victims on the island of Utøya. The striking proposal, with a harsh, three-and-a-half-meter-wide cut into the peninsula facing the island, went viral almost instantly, initiating an intense public discussion around the design of the monument, and ultimately what is an appropriate format for mourning. The discussion lead to the government’s undemocratic decision to cancel all contracts and replace the artist’s proposal with a more conventional site for mourning. Dahlberg comes across as an impressive personality who, rather than dwelling on his wounded ego or forcing his project into life in his film, focuses on the need to memorize the event. In essence, the film reflects on individual grief as a personal issue, but it also shows that there is such a thing as shared mourning and public memory, which are political entities. It may be that this time-consuming project of understanding the differences between private affectations — as sincere as they may be — and public responsibilities, will play out as one of the exhibition’s strengths: as a force for good, a healing power, but also one that raises unforeseen questions.