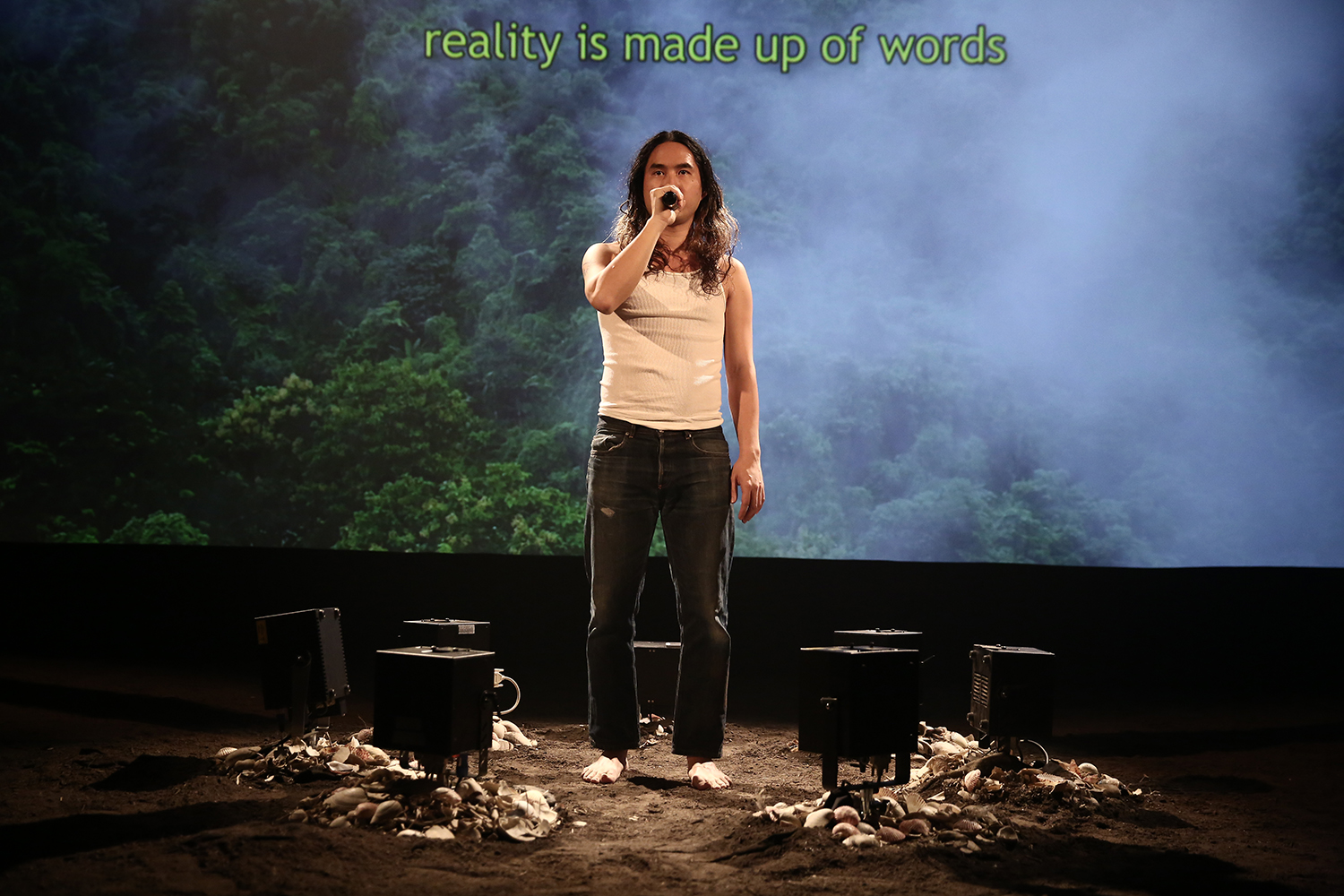

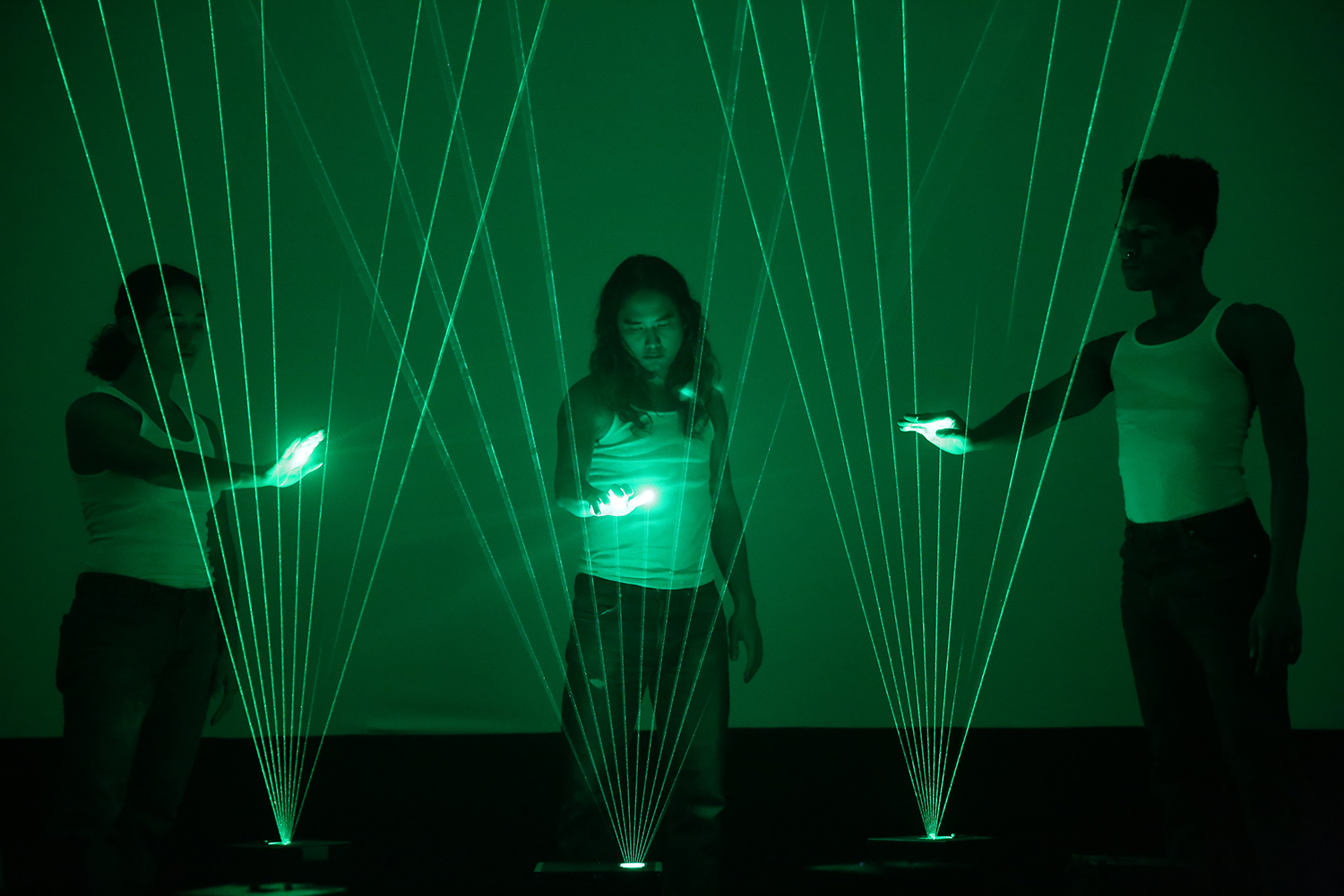

Korakrit Arunanondchai’s Together, created in collaboration with boychild and Alex Gvojic, is a live cinematic installation that calls itself a performance in an “outdoor cinema.” The work, commissioned by Performa 19, emergedfrom Arunanondchai’s long-held interest in thinking storytelling as a strain of animism. Together spatializes a work of “ghost cinema,” a post-Vietnam War phenomenon, but also interweaves the 2018 Tham Luang cave rescue — read as a parable of citizenship conferred to four stateless rescuees — alongside histories of American military occupation, into a complex, lived mythography. This cinematic catharsis is inhabited less from within the screen than from without: at one point, performers paint themselves a thick white, from animal ashes, ghosting themselves into proto-cinematic projective surfaces. Boychild presences herself in silhouette from behind the screen, and Arunanondchai, spell-teller, floats throughout.

Emma McCormick Goodhart: Can you unfold the spirit that possesses Together through poetic, choral conjuration?

Korakrit Arunanondchai: In my videos prior to Together, I was researching an animistic Buddhist god concept called the nāga, a mystical snake. It’s very common in Southeast Asia, and it’s sort of Hindu but it also exists in Buddhism. It’s almost like a mascot, for Thailand at least, to the temple. Sometimes you can take certain grand narratives, then explode them apart and see which parts of them remain real — which parts aren’t constructed for propaganda or state purposes. I was trying to think about the nāga outside of Buddhism. Buddhism in Thailand has always been a statecraft mechanism to build or pool power in the center, and to define borders. The nāga, for me, feels like an anarchic force, because it’s like magic — like trying to govern magic. I went to this region in northeast Thailand, where there is a really strong belief in the nāga, almost like Buddhism, but with more belief in ghosts, magic, and mysticism. The region was interesting to me, because it has this strong mysticism towards the Naga, but it also has ties to the military: the biggest American military air force base in Southeast Asia used to be there during the Vietnam War. There’s also a secret prison that the current head of the CIA used to run. I’ve gone back to this one area three or four times to shoot videos.

EMG: A highly haunted geography, then? How did you come to manifest your notion of an “outdoor cinema” at Harlem Parish?

KA: Haunted, or rather, historically rich — and maybe still active. When I went to this nāga worship place, I found there was a famous story about an outdoor cinema, where ghosts hire outdoor projectionists to show a film. People show up wearing all white to watch the film; the projectionists fall asleep, and when they wake up, they’re in the middle of nowhere, the people are gone, and the money they received has turned into leaves. This happened about thirty or fortyyears ago, but the projection company is still there and shows a film every weekend. You can think about ghost stories as advertisements for magic. That a place is somehow strengthened by stories or myths about supernatural things, regardless of whether they actually happened or not. The origin of ghost cinema is based on a tradition where monks would project movies on temple walls. The audience or the projection was, essentially, a ghost, and people would come to sit with ghosts and watch a movie, reenacting, in simplified form, what a ritual is. A communion of ghosts. A communion that begins through the projection: the story that’s outside of the body. A ghost being a story that’s embodied in a body that’s a nonhuman body. There’s this whole ghost-host — a process of possession — which film becomes the perfect medium for.I wanted to set up the installation as a cinema, but also to use the screen as a character. That’s why boychild, who plays the nāga or the ghost, sometimes appears from behind the screen. I think that, together, the dirt and the screen created a confusing enough space.

EMG: How does sound function in this expansive configuration? I was struck by how voices emerge from all sides of the screen: from you, from the film, from behind the screen. How were you thinking about staging voice — and about your in-person presence as oracle-storyteller in contrast to the “voice of America,” or voice of news footage, voiced in absentia?

KA: I worked with two musicians, Aaron David Ross and Bonaventure, on this piece, and we put a lot of effort into making sound surround-ish. Specific things only came from specific speakers. Boychild’s voice of the ghost only came from the top, the drone only came from the bottom, and my voice only came from the front. We were thinking about what my performance would be if the screen disappears, or if I appear out of the screen. About what would happen if the story starts to possess these different sites of expression or storytelling — moving into the thirteen dancers, or into me, or into boychild. Essentially, it’s like an expanded cinema: a cinema that expands out and into the space. The screen’s another character in the room. I was thinking about this piece in relation to the video; how it could almost be like a video flipped backwards. The first scene in the video is about an outdoor ghost cinema in a nāga worshipping place. I wanted to unfold actions in the video in the performance, so that in the end, the audience and the performers turn, together, into this scene, watching people watching.