How do pictures work? This question resonates throughout Francesco Zucconi’s book Displacing Caravaggio. It is a question whose tone is in line with the intellectual tenacity of Aby Warburg’s iconology. Also, its framework seems to indicate a need to distinguish what is at stake here from other interpretive domains; for example, those belonging to ontology (what pictures are) or semiology (what pictures mean).

How do pictures work? This question resonates throughout Francesco Zucconi’s book Displacing Caravaggio. It is a question whose tone is in line with the intellectual tenacity of Aby Warburg’s iconology. Also, its framework seems to indicate a need to distinguish what is at stake here from other interpretive domains; for example, those belonging to ontology (what pictures are) or semiology (what pictures mean).

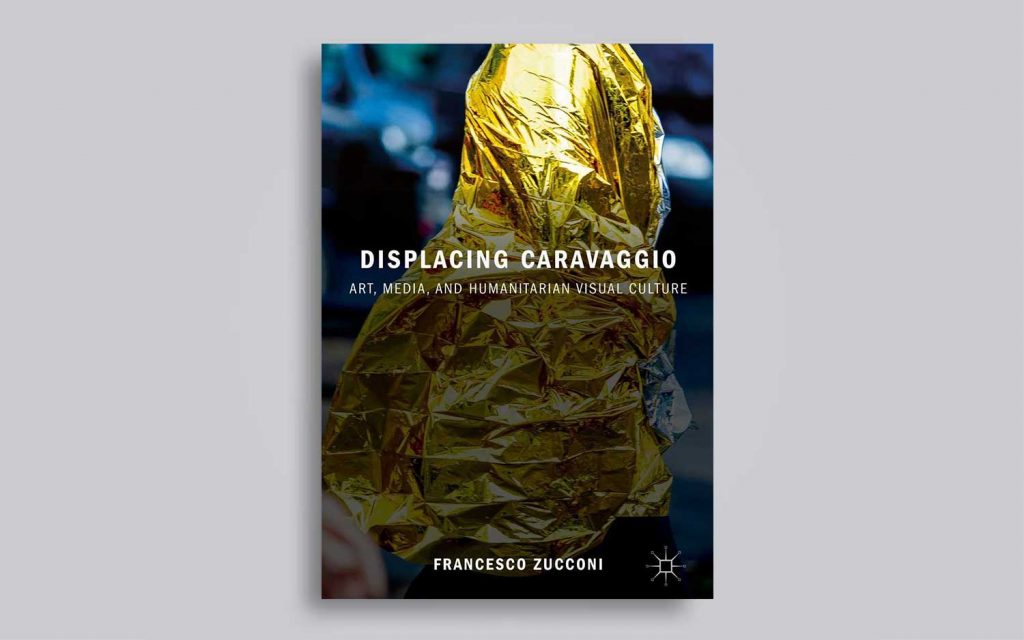

Given this premise, we might consider this book as a kind of cultural symptomatology — a discourse committed to investigating a palimpsest of specific signs. That is, those “forms of visual manifestation of the gestures through which the values of mercy and humanitarian assistance have been regenerated over the centuries.” All this from Caravaggio’s paintings as seen via different and intertwined vantages.

After a necessary introduction on so-called “humanitarian archeology,” in which Zucconi draws attention to three main topics in his reading (passion, mercy, and the dispositive of the person), the following sections open up a gradual anti-essentialist approach in his thinking.

First, he explores “the problematic tension introduced by the painter between the immanence of gestures and the transcendence of iconographic models” in comparison with contemporary cases of humanitarian art, e.g., NGO campaigns and World Press Photo contests.

Second, he delves into virtual reality and, specifically, into some of its applications. In this regard, it is worth mentioning the link between the Italian artist and VR cinema that the author identifies with the gyroscope’s functionality.

Third, by taking into account a recent episode, inscribed within the current migrant crisis in Italy — the exhibition “Towards the Museum of Trust and Dialogue for the Mediterranean,” which took place in Lampedusa, 2016 — as an occasion “for questioning the limits and aporias of humanitarian discourse.”

In the final chapter, “On Displacing,” Zucconi proposes a theoretical standpoint through which a specific iconological use of Caravaggio, from art criticism to visual literacy, may help to analyze the current mediasphere of suffering and, therefore, those media images that inform our perception of traumatic events.

By embracing “the notion of displacing as a theoretical and methodological paradigm for the humanities,” the author wisely points out one of the central themes in politics nowadays. Namely, the necessity to rethink the idea of borders, a task in which the contingency of art may work “to innovate and interrupt the performance of the present.”