Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

Arriving in Sweden in the 1980s, having fled Palestine in the 1970s, Tarik Kiswanson’s father presented himself at an immigration office to register for work. Upon inspecting his application, an immigration secretary suggested that his family surname, Kiswani, originating from Jerusalem, could become a problem when looking for jobs. At the time unmarried and childless, far away from his country and family, she conferred him a seemingly miraculous solution. Changing his surname by adding the suffix “–son” would introduce him to an etymological linage at the root of Scandinavian society. And so he was marked — like many others were at the beginning of life in modern-day diaspora — as being in a permanent state of in-between.

Born a Kiswanson — a child of exiled Palestinian parents in a small community in southern Sweden — this Swedish-, Paris-, and Amman-based artist operates within an inherited condition: a feeling that he describes as “being neither of here nor there, but in a constant state of floating, oscillating somewhere between the past and the future.” Though perhaps mostly known for his painstaking sculptural works — where, for example, he polishes sheets of stainless steel until they become gleaming mirror surfaces to be used for various structures — the artist has been employing performativity at the core of his practice. Whether through an object or live event, Kiswanson facilitates encounters with the in-between. In the process, the artist troubles the political, social, and affective realities associated with notions of identity and belonging, particularly how these can be determined by multigenerational experiences of migration and embodied cultural heritage.

Looking at the cut-up, at times woven, surfaces that comprise many of the artist’s wall works, viewers are faced with a shattered version of themselves and their surrounding environment. Reflections move from one surface to another across works that are placed in oppositional locations in a room. This feeling of displacement — of seeing oneself multiple times, in multiple places — is a recurring technique in Kiswanson’s work, one that perhaps has more to do with his efforts to unpack complex processes of perception than with materializing an experience of geographical dislocation.

The artist pushes away from any simplistic trope of self-representation, instead making formal choices that place experiential details at the core of his work, entangling the viewer in a process of facing their own phenomenologies. In doing so, Kiswanson manages to render himself visible and invisible, appearing through the movement he choreographs in other people’s bodies while simultaneously managing to disappear his own.

Entering one of his works from the series “Vestibules” — dome-shaped structures formed of long polished steel and brass strips that hang from the ceiling — can induce a dizzy spell. A vestibule is both an organ in the ear that regulates balance (vestibular system) and, from Roman and Middle Eastern architecture, a space that you pass through to arrive somewhere else: an “in-between.” Inside one of them, the movement of the viewer determines the experience of the work, shifting it from kinetic sculpture to a site that facilitates an intensified engagement with the self, not only through a myriad of reflections but through a process of disorientation.

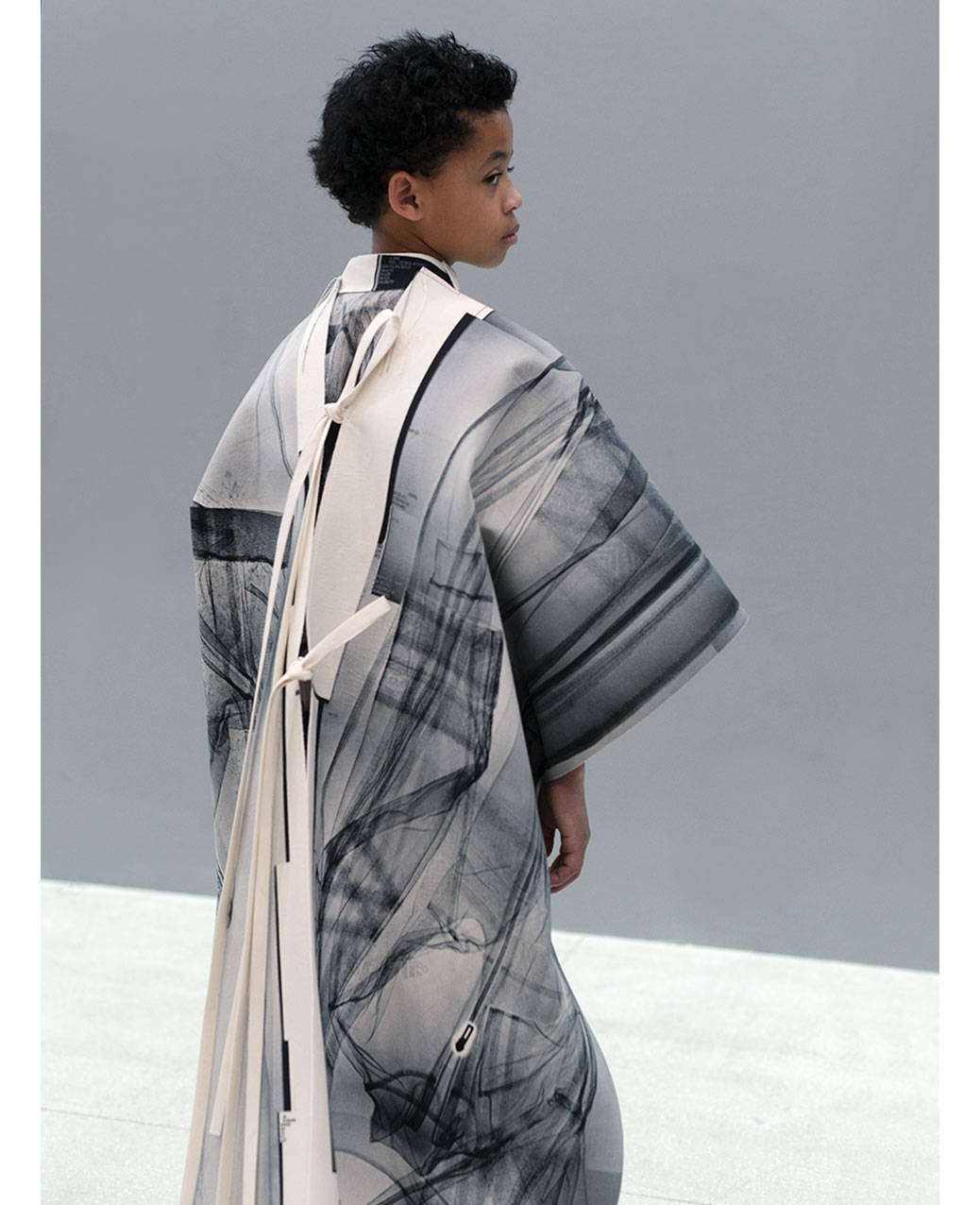

Pulled from the movement in Sufism practice — a strand of Islam defined as “Islamic mysticism” — whereby whirling incessantly is a form of physically active meditation, Kiswanson later introduced a pair of young boys, Haytham and Emil, as performative activators of the “Vestibules.” The children, dressed in bespoke canvas cloaks, would come into the space, mostly unannounced, enter the sculptures and start turning, slowly opening up the metal strips like cloth in the motion of wind.

The experience of working with these eleven-to-thirteen-year-old boys — who were intentionally cast for their mixed cultural identities, shared between Europe and North Africa — opened a new choreographic field for Kiswanson, one where preadolescence became a point of departure for exploring the liminal space between childhood and adulthood — a temporary state during which the body and mind are unburdened by the transformations that will soon render them “in puberty,” provoking a heightened sense of self-awareness in relation to others around them. This research — a continuation of the artist’s probing of the experience of being “in suspension” — has over the past few years taken the form of performances, poetry, drawings, sculpture, and sound, much of which was recently brought together in one of Kiswanson’s largest performance commissions to date.

Dust is the title of the artist’s installation and roughly thirty-minute live work that was presented at Centre Pompidou in Paris as part of “MOVE 2019,” the institution’s annual (since 2017) live festival, curated by Pompidou’s own Caroline Ferreira. Here, Kiswanson took over a large passageway space in the museum, able to be entered by audiences from different points, to construct a sculptural and sonic environment that was intermittently activated by three preadolescent performers.

Keryan, Tidyan, and Noa live within the suburbs of Paris and, like Kiswanson, they are all third-culture kids: children who have grown up in a culture other than their parent’s own. In this way they are French, but they are also Ukrainian, Congolese, Algerian, Swiss, and Haitian. Through recorded and spoken-word deliveries by the performers, which reflect on the human condition in relation to thresholds, borders, and states of being that may initially appear to be at polar opposites, Kiswanson compels the listener to reflect on the construction of identity in a state of social and bodily in-between: one where memory, both one’s own and that which is passed on, exists far beyond lived experience.

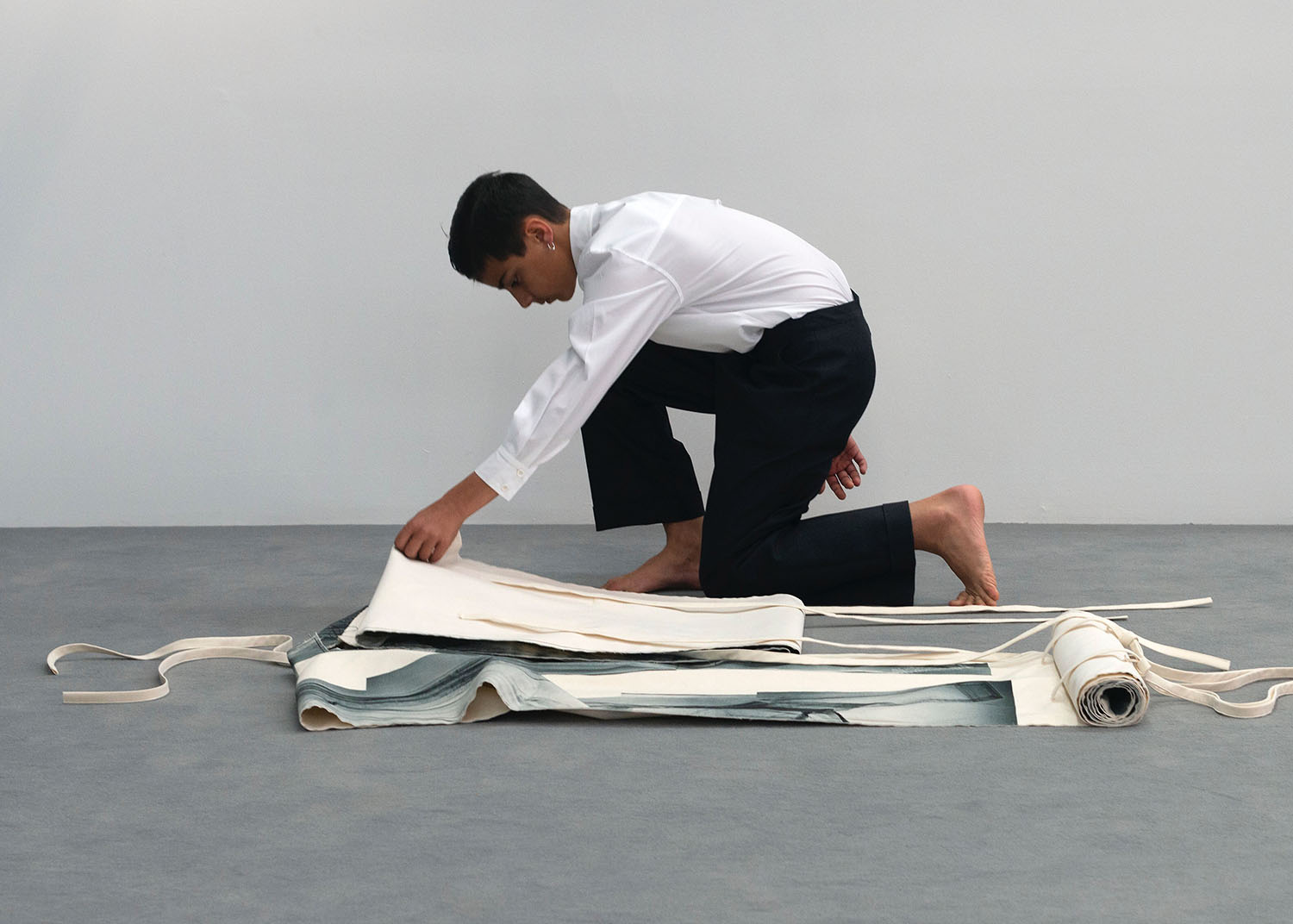

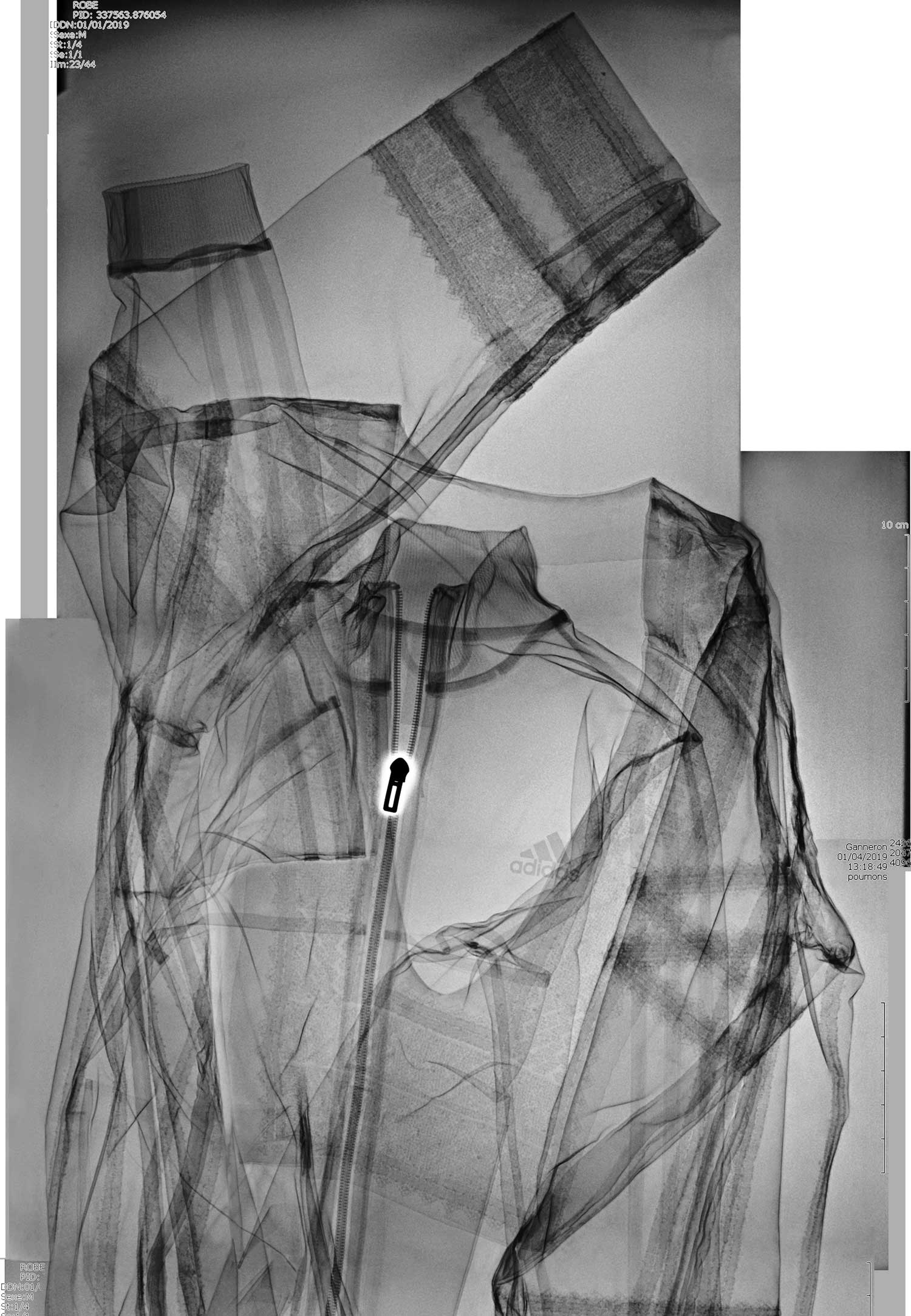

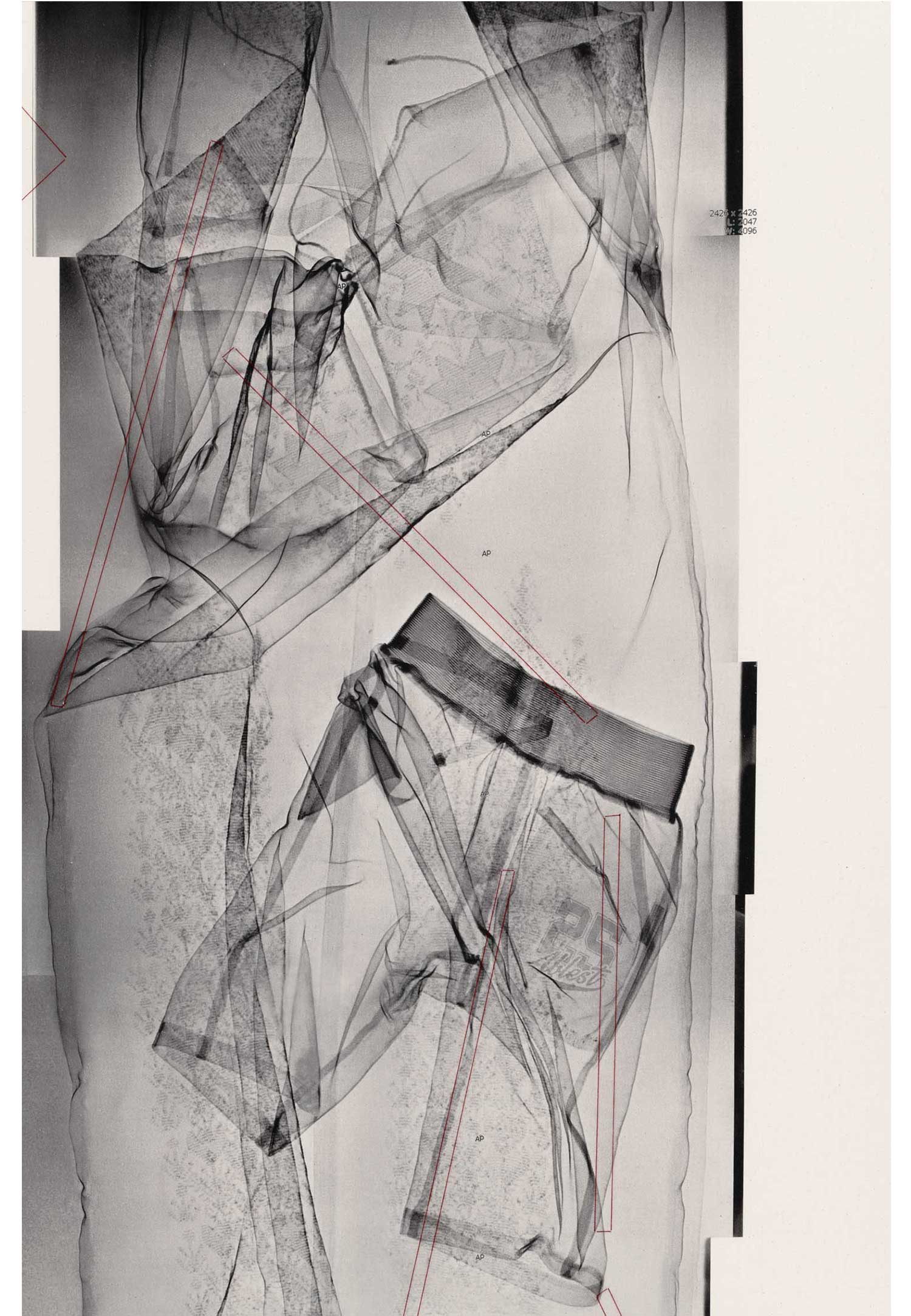

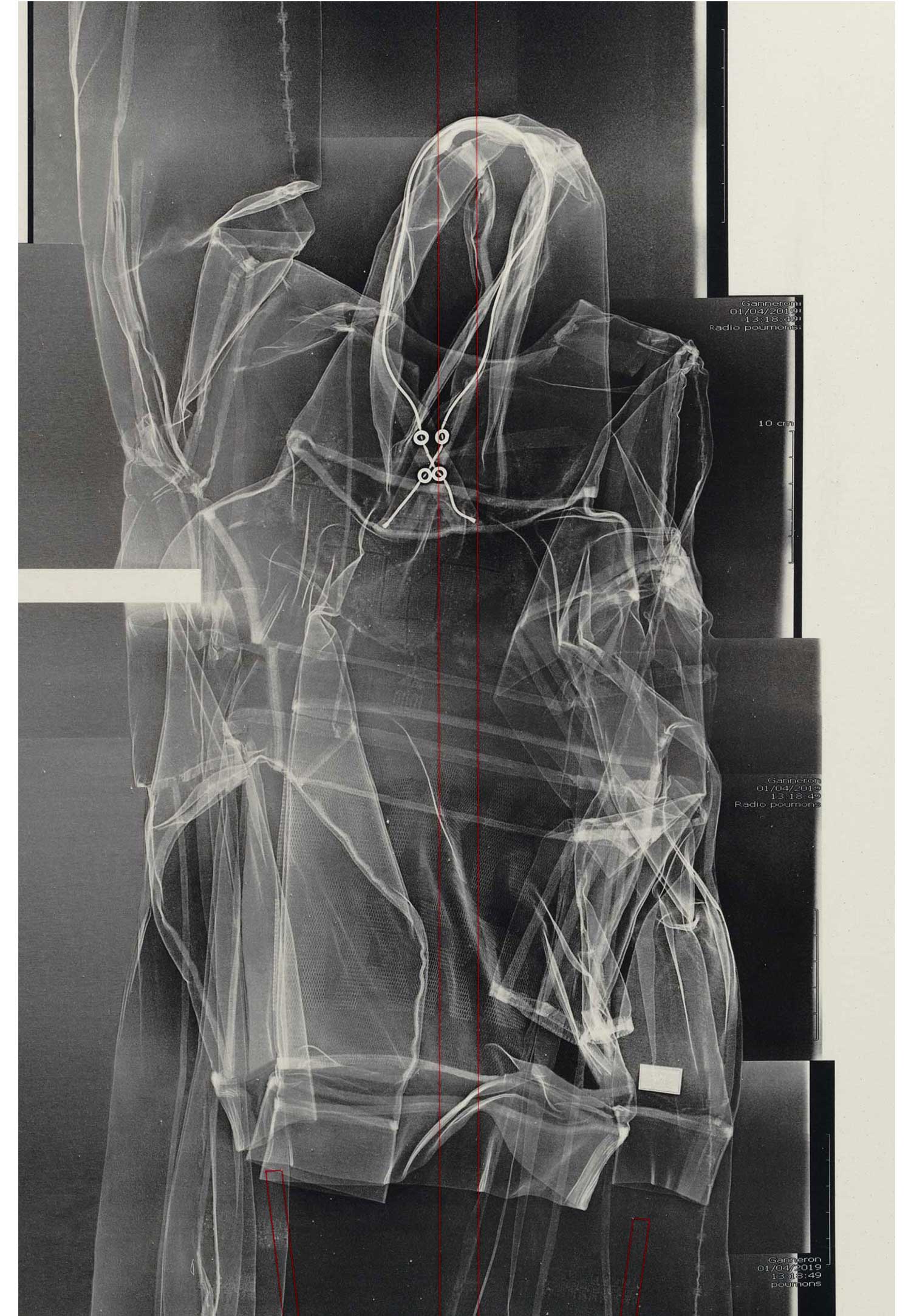

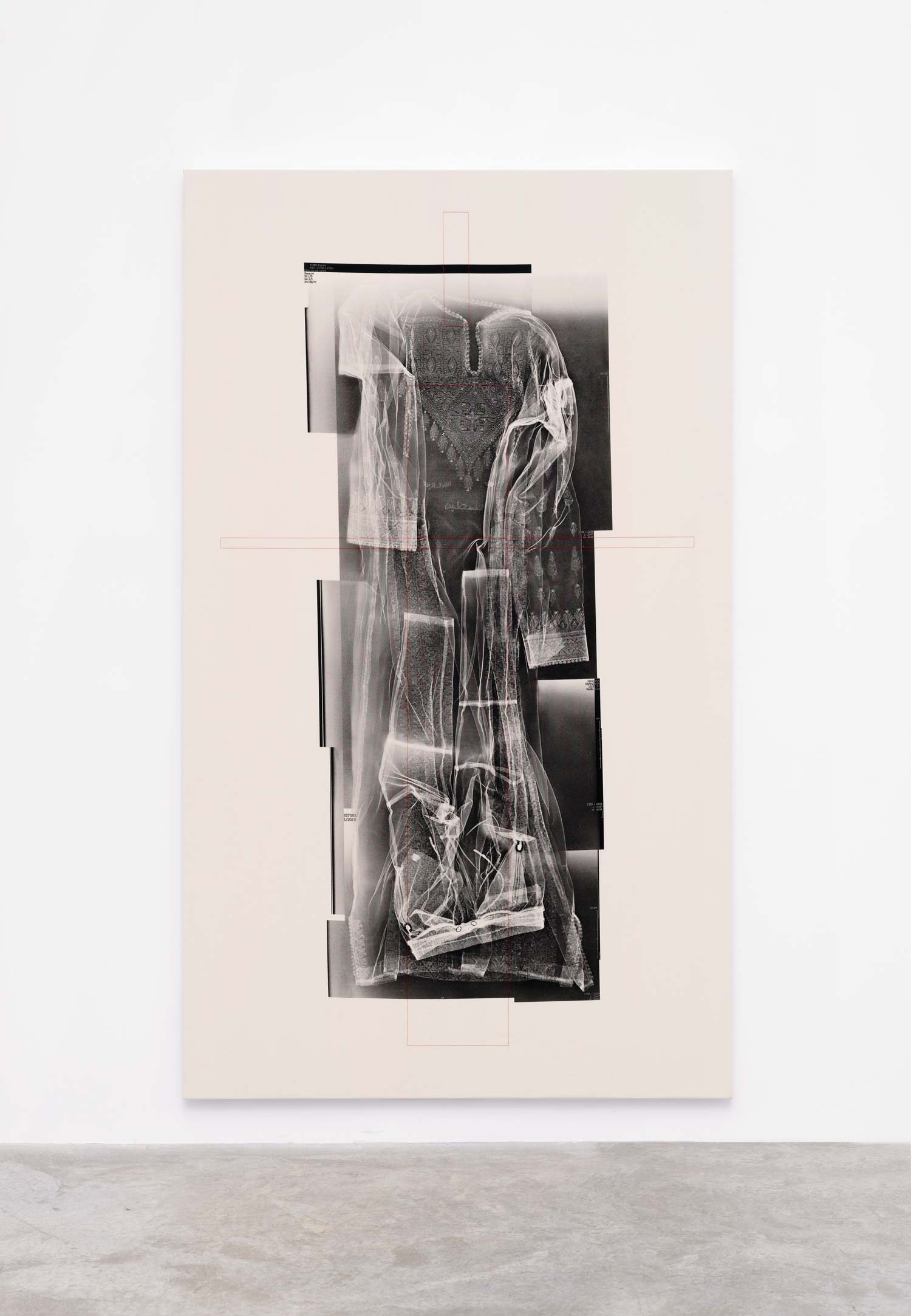

Alluding to this process of identity formation as multiple, but also as a constant state of renewal and regeneration, Kiswanson dressed the performers in several layers of clothing that were revealed and carefully shed as part of the performance. Printed on the first layer — comprising a purpose-made canvas cloak, similar to the ones previously used by the artist — were printed images of ghostly X-ray compositions. The artist’s Passings were sown together by hand by a borrowed atelier from the Parisian fashion house of Lanvin, and feature a composite of radiological scans depicting an assemblage of pieces of clothing. Here, various dresses from the Arab region — loaned from the Tiraz Foundation in Jordan, home to more than two thousand Arab costumes from the nineteenth and twentieth century, much of which would have otherwise disappeared — are arranged with pieces of contemporary clothing belonging to each of the performers. In one of the compositions, Noa’s Adidas sports jacket meets the complex embroidery of a Jordanian robe, its metal zip conjoining them as one garment. In another, a pair of Keryan’s sweatpants and a Syrian dress meet to form a hybrid, nongendered piece, obfuscating its original design and purpose.

Kiswanson’s archaeology of dress is as much an effort of resurfacing cultural pasts as it is of transforming and bringing them into the present, creating a physical and spiritual connection between the performers and their — and the artist’s — generational predecessors. The artist’s gesture is that of re-inserting these histories within affective and visual proximity to contemporary life, subtly nodding toward the ways in which Western culture so often seeks to erase difference.

Entering the space with these charged costumes, the performers unfolded a choreographic structure that was as much built around movement as on states of being, perceiving, and looking. Though a performer may come into the room, giving away the perception of a beginning, he may stand next to an audience member for an indefinite period of time, at some point directing their gaze to someone, unannounced, only to remove it seconds later. This effort to create a suspension of time, which is particularly remarkable because of the performer’s skill in holding the attention of a room full with people, most of whom are adults, facilitates a strange situation in which this child is not really a child, but a commanding force of presence akin to an otherworldly being.

To achieve such situations, Kiswanson creates an environment in which his young performers retain a belief in their ability to have control over what is happening, something that is undoubtedly palpable in the confidence of their deliveries. Such control was also afforded by pulling from the performer’s own strengths, in particular their backgrounds as dancers across the disciplines of hip-hop and dancehall, choreographic cultures developed within the suburbs in the city. Kiswanson, who for the first time purposefully sought to work with these skillsets, sampled movements from each of the performer’s dance vocabularies and extended them, both in duration and form, to create new deliveries that strangered their potentially familiar reception.

Here, a performer lifts his body with his hands on the floor, subsequently dropping to the ground; the action is repeated multiple times in a state of alienation. Another performer may appear to begin to slowly dance, only to return to their starting position, and then shortly begin the same action again. Running, faltering, falling, lifting: all are actions encountered throughout a choreography in which the performers appear to be going somewhere. But when reaching a point of arrival their bodies seemingly give in, never fully arriving. Throughout, Keryan, Tidyan, and Noa engage with one another in tender and generous ways, holding each other’s bodies, shielding their eyes, touching their fingertips, and embracing each other with filial care, furthering a feeling of their journey as shared.

This impossibility of reaching an end, or feeling captured by a feeling of resolution, rendered the performers in a constant state of motion, one with rapidly changing effects. It is a question of the passing of time — both choreographic time as well as real time. The inclusion of a curtain composed of thin strips of polished metal in the middle of the space and the setting of the performance in the cusp of the afternoon’s sunset created a situation in which light — in its movement through the room’s windows — bounced off of the mirrored surfaces and created a myriad of changing reflections throughout the space and the performance. What you might see in one particular moment would be different in the next; what you might encounter on one day would be nonexistent on another. Toying with ephemerality as a condition of the work, Kiswanson further alludes to the malleable nature of identity formation at this stage in the performer’s lives. They are unable to be fully defined.

Kiswanson will present a final iteration of this body of work as part of the Performa 19 Biennial, taking place November 1–24 across New York, but he will likely never be able to restate this performance again; at least not in its same configuration. Keryan, Tidyan, and Noa will soon enter new phases of development. Even a year from now, the performers will have grown up. Their sense of self might be different, and their bodies will have changed. They might be taller, broader; their costumes will no longer fit. For those who witnessed their performance over these days in Paris, Kiswanson facilitated an encounter with something at the brink of disappearance: as fleeting and ungraspable as dust.