“My mission is to spark joy in the world through tidying,” says a smiling Marie Kondo — the pop-culture tidying guru whose mission is to get rid of all negative things — in the trailer for the show Tidying Up with Marie Kondo. Her method of decluttering involves asking whether a given object sparks joy; if not, it should be discarded. Out of sight, out of mind. Landfills around the world are overflowing with things that don’t spark enough joy and don’t fulfill our expectations for a “good life,” to put it in the words of Lauren Berlant. Indeed, in her pivotal essay Cruel Optimism (Duke University Press, North Carolina 2011), Berlant reveals the injurious attachments we have formed to fantasies of the good life that are no longer sustainable in the present.

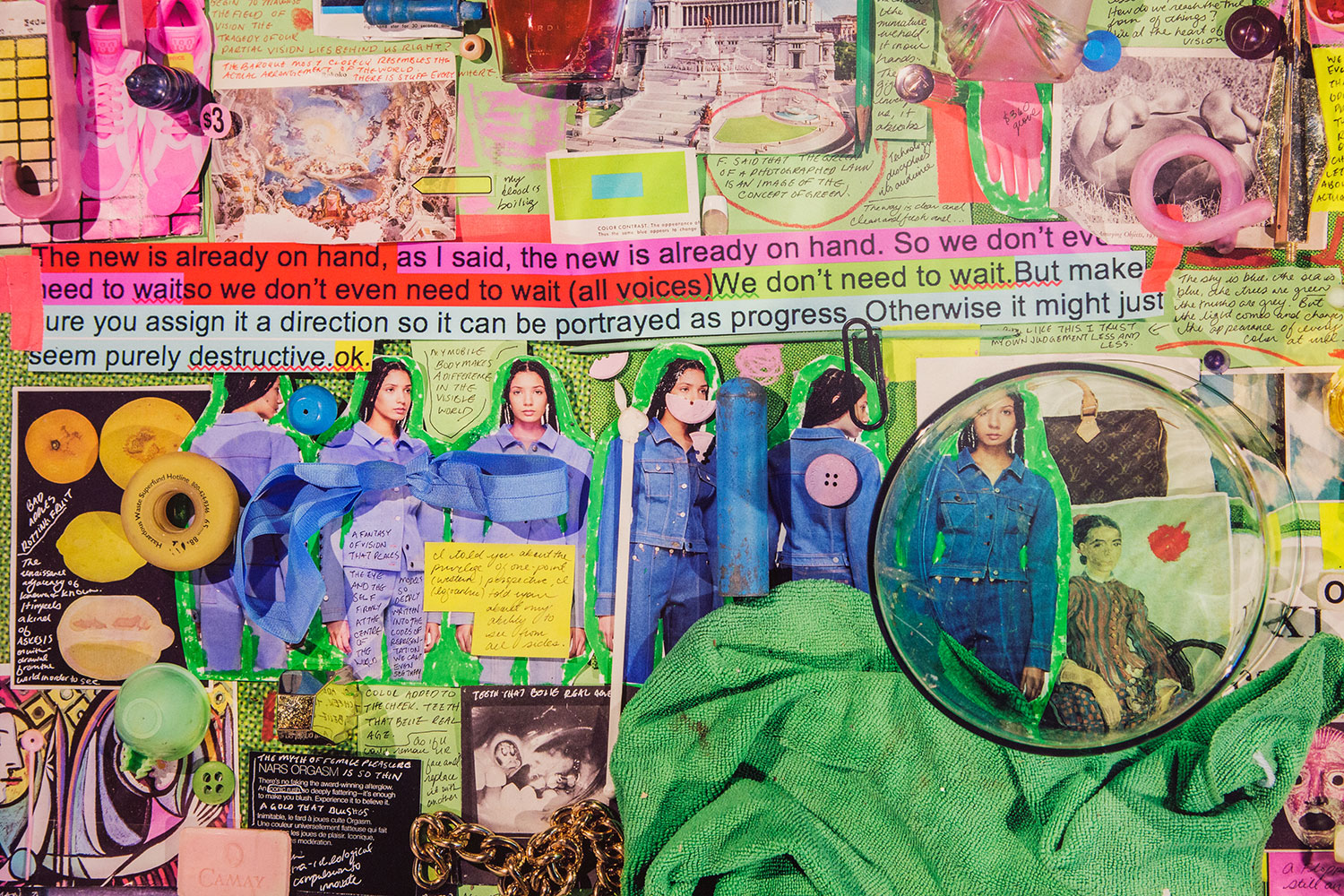

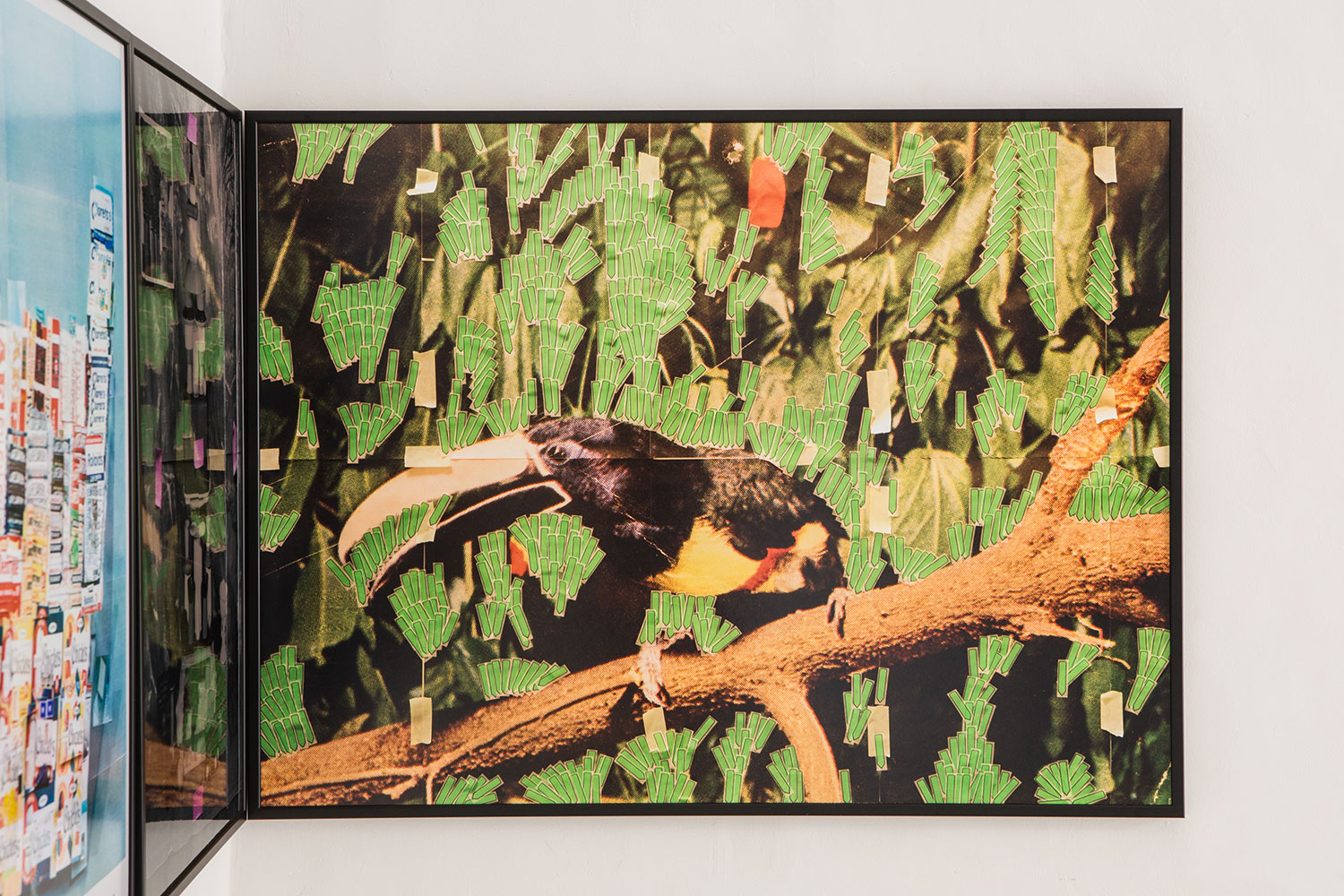

Titled “Good Life,” Sara Cwynar’s exhibition at Blitz in Valletta, Malta, unpacks this ideal, dismantling stereotypes under the hegemonic nature of images. The exhibition surveys her practice since 2013, showing Cwynar’s multifaceted approach to the languages of photography, collage, and filmmaking. Found objects and images play a vital role in her compositions, which suggest modern trompe-l’oeils. Her prints, from Toucan in Nature (post it notes) (2013) to A Rococo Base (2018), are a result of a process of re-photographing printed images, on which found objects, transparencies, and archival images are superimposed. The tension between two and three dimensions is tangible. These multilayered pictures, which combine elements of photography, sculpture, and collage, reveal their fictional status to the viewer and “tackle the critical concept of visual truth” (to quote Dolfi Agostini in her curatorial essay).

But it is in video that Cwynar perfectly reflects the iconic bombardment to which we are subjected every day. Exploring the notion of standardization, she shows what it means and how it influences our user experience. In Cover Girl (2018) she examines how standards of beauty are imposed on women, intertwining images of Tracy (a model and friend of the artist) with footage of a make-up company. Her first video work, Soft Film (2016), addresses the “soft misogyny” that dominated the news at the time she was making it. Here, an overlapping voice-over presents a taxonomy of personal objects.

Cleanfluencers, lifestyle masters, and fitness gurus are retooling our cognitive biases, stuffing our Instagram feeds with yoga exercises, healthy food, and clever ways of cleaning the closet. This unending display of living life to its fullest is meanwhile tainting our notion of reality. In this sense, Cwynar’s exhibition offers itself as a keen inquiry on the economy of images and their circulatory power. Red Rose (2017), Magenta Rose (2017), and Pink Rose (2017) are three macro photographs of roses with perfect colors — so perfect they seem artificial. Today, as Steven Shaviro has observed, “the opposition between reality-based and image-based modes of presentation breaks down, and the most intense and vivid reality is precisely the reality of images” (Post-Cinematic Affect, O Books, 2010). Are Cwynar’s roses real or synthetic? The answer is that it doesn’t matter in an era of simulation.