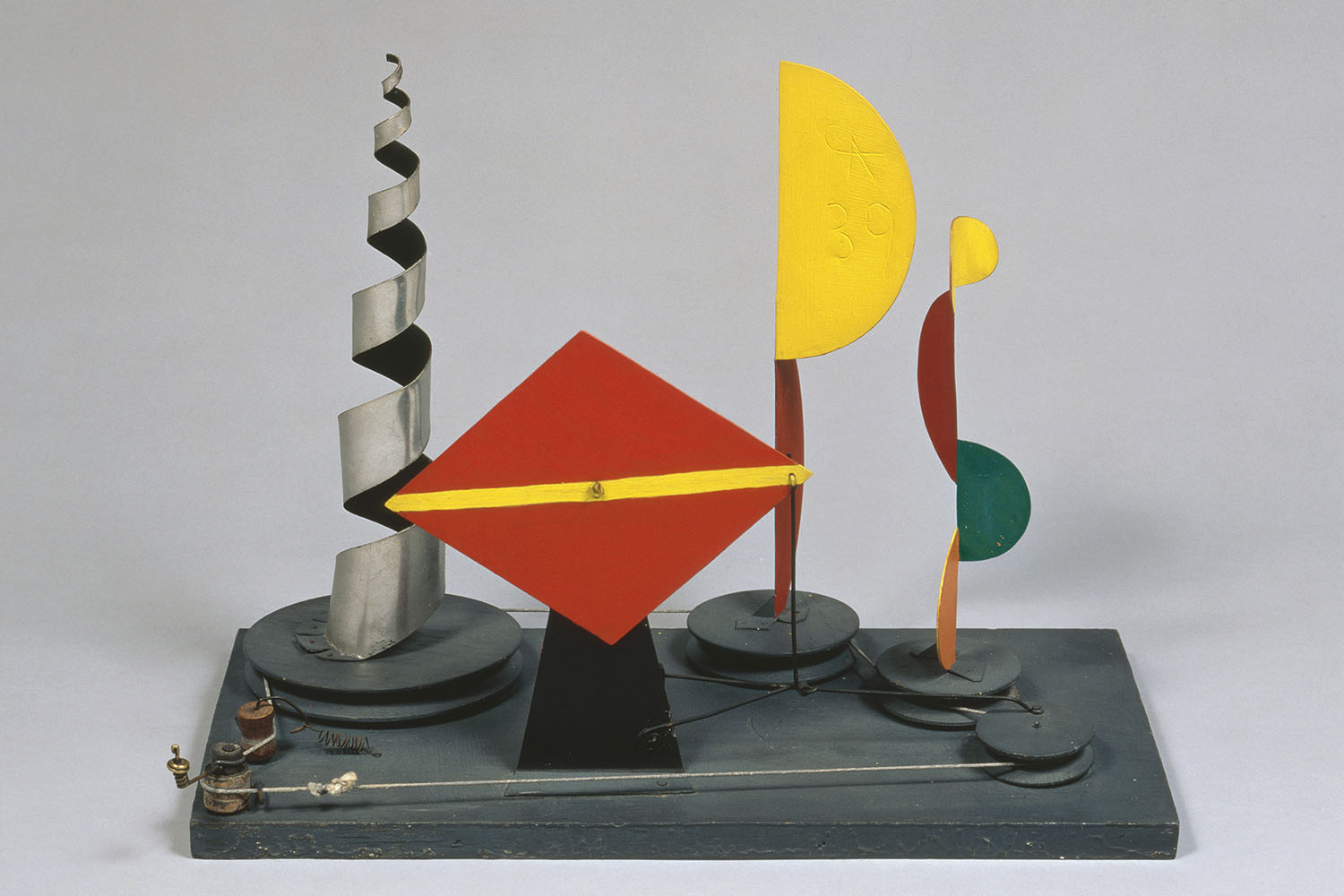

Each “Calder Story” at Centro Botín is an untold one. More than eighty mobiles, maquettes, and architectural projects are on display, all beautiful attempts that never arrived at a final destination. These objects, studies, sculptures, and collaborations connect the dots between Calder’s personal relationships, obsessions, and frustrations; one such important and “beautiful mistake” was the Chase Bank commission in Manhattan, which ultimately went to Jean Dubuffet.

Director Benjamin Weil explains how the curator of the exhibition, Hans-Ulrich Obrist, has studied the Calder archives since 1990. With the help of the Calder Foundation and the artist’s grandson, Sandy, Obrist was able to view previously inaccessible materials, where he found an extensive selection of unrealized projects.

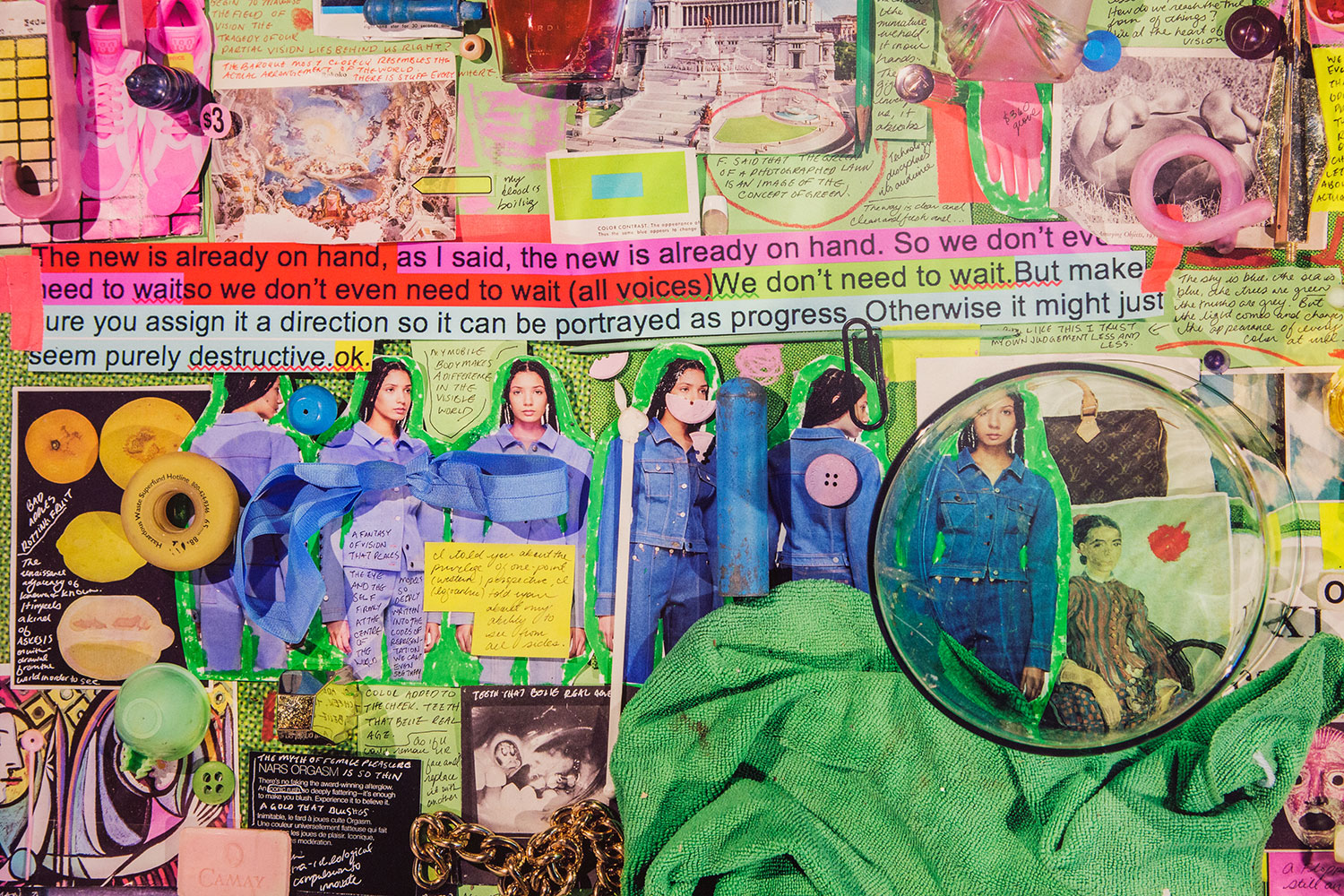

“Do you remember when I started my curatorial activity in my kitchen? Every couple of years I think it’s important to go back to that format, both physically and metaphorically, and focus on very intimate shows.” Hans-Ulrich Obrist introduces the exhibition with these words.

Obrist recalls his first visit to Calder’s studio in Roxbury, where he could see all “the main ingredients to his projects: from metals to tools, his inks, and papers, exactly as he left them.” Originally, “Calder Stories” was envisioned for a place such as the studio, but then the invitation from Centro Botín in Santander came and, as Calder probably would have hoped (his studio was too much of fragile place), the show was then built in the Santander museum. As viewers take in various mobiles, they learn that one project was intended for Beirut, another for India or Guatemala. In this way, Calder embraced the idea of globalization back in the 1950s. He would work in other countries with the existing materials of the place, immersing himself in other cultures. His presence abroad, as Obrist describes it, was always soft, almost as floating.

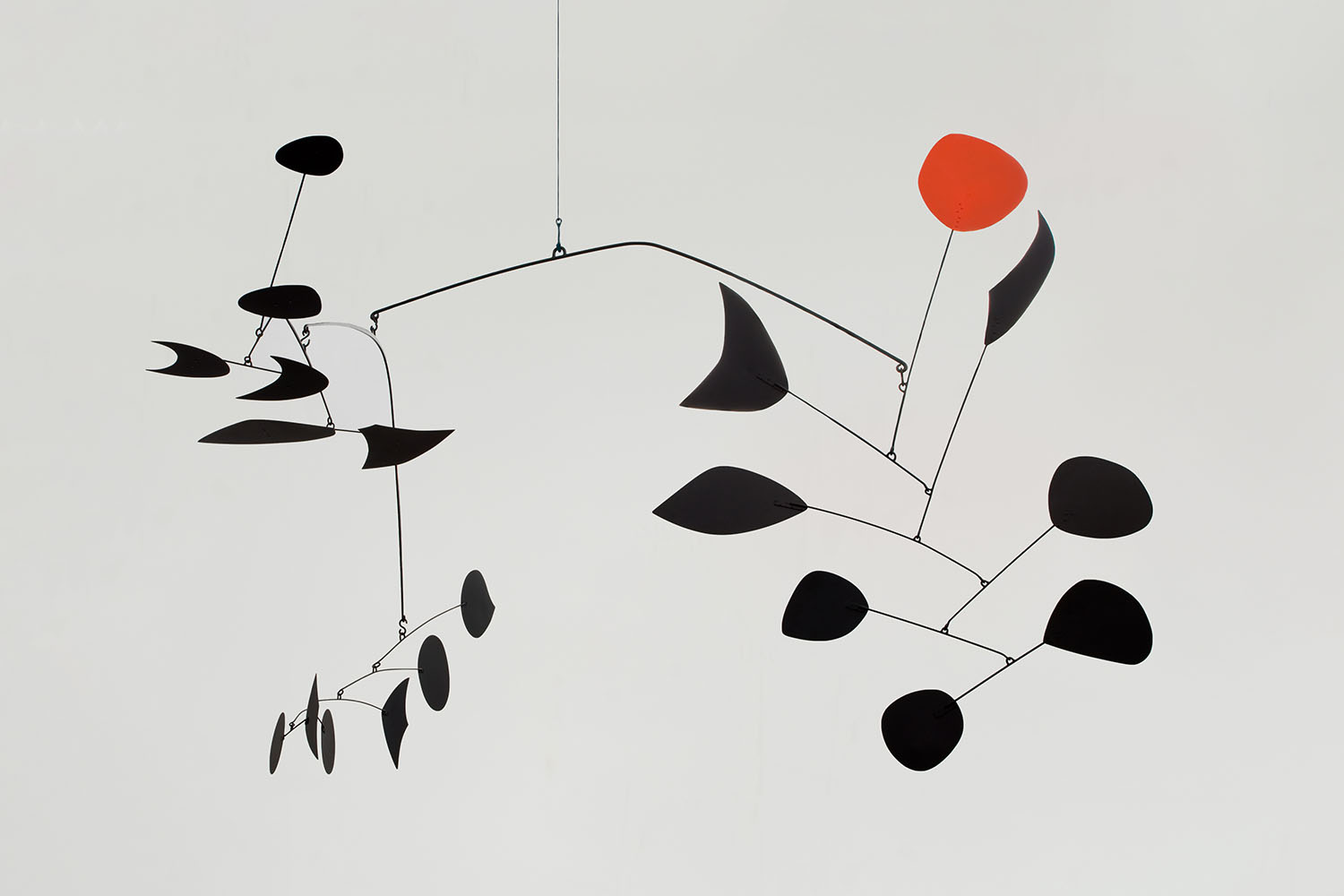

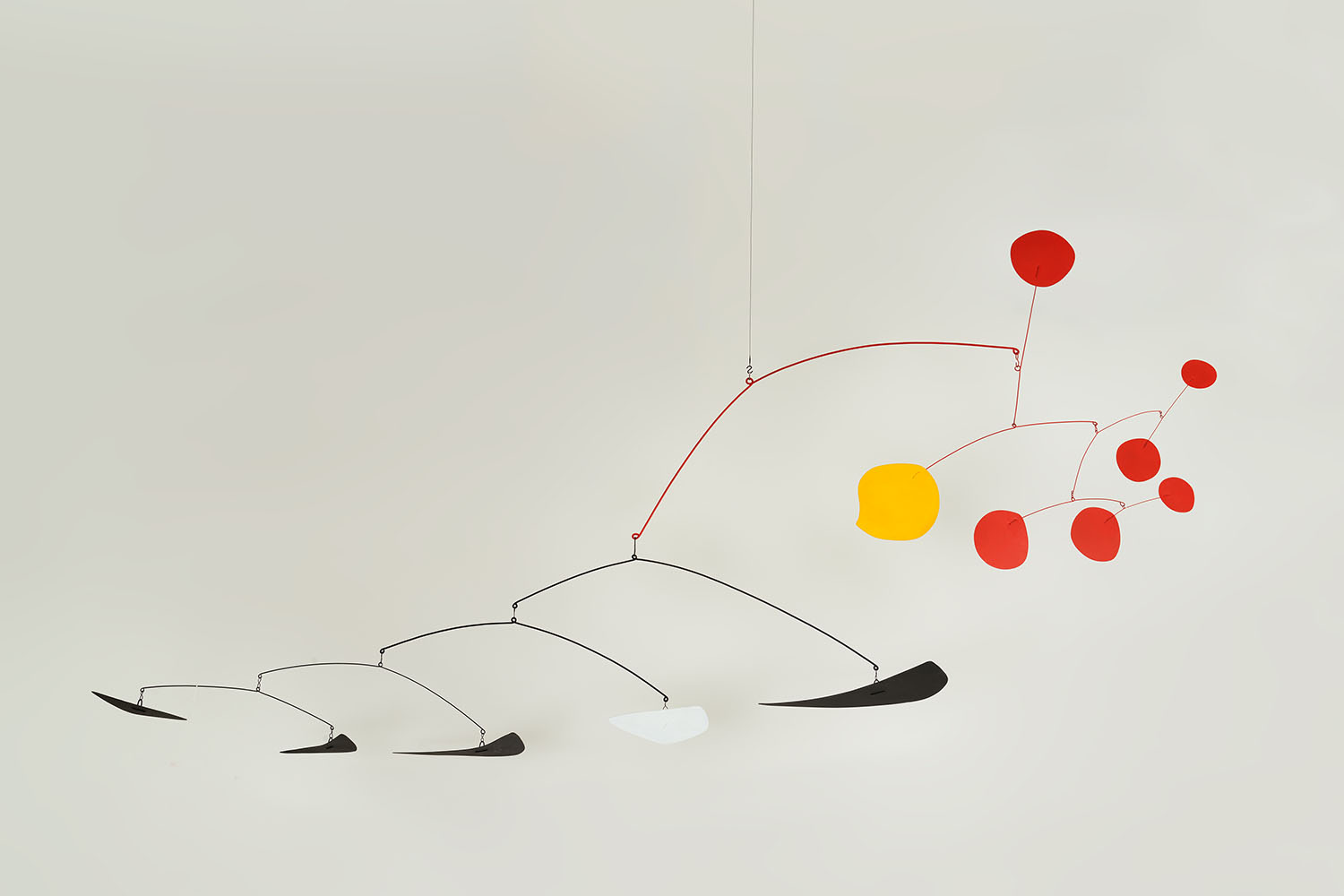

The main room of Centro Botín, lit naturally on long summer days, brings even more life to Calder’s works. They take on a human appearance, as if part of an ongoing interaction, ready to give birth to something bigger. The floating structures, designed by Centro Botín’s architect, Renzo Piano, function as elegant and noninvasive platforms. There are no walls, no claustrophobic rooms: everything, from the objects to the installation itself, floats. Piano echoes the structure of the building and projects it into the rooms. The sense of floating is tripled: the floating of the building, the floating of Calder’s stories, and that of the platforms.

This exhibition somehow provides a new perspective on an artist and body of work that has been extensively studied and exhibited. Both the idea and the installation are unexpected, offering an as-yet-undiscovered side of Calder. As Obrist remarks, “I am always interested in adding light to blind spots.”

Calder Stories is open to the public until November 3rd, 2019