In her 1992 novel The Secret History, author Donna Tartt details the story of a group of youths studying the classics who, in their zeal for the subject, set out to recreate a bacchanal. “One mustn’t underestimate the primal appeal,” a character insists in regard to their goal, “to lose one’s self, lose it utterly.” Such ambitions imply that the bacchanal, in its hedonistic ecstasy, is a dead activity, lost to the realm of antiquity. In her work—which spans performance, video, ceramics, drawing, and photography—London-based artist Zoe Williams restages these feasts of excess, as seen in performances such as Ruffles (2019) in Monte Carlo or Ceremony of the Void at London’s David Roberts Art Foundation in 2017, both of which included an artist-led ensemble participating in what could be described as a Dionysian, lascivious affair. That audience members in Monaco took the content of Rufflesas an affront, going so far as to ask Williams if the work “was about them,” proves that these lavish gatherings are not, in fact, obsolete, but rather very much alive.

In my exchange with Williams, we spoke of Carnage UK, the highly popular event series designed for university students across the United Kingdom, in which partygoers drink to excess during a seven-hour pub crawl, leading to “uncivilized behaviors” including public urination, copulation, vomiting, passing out, and general belligerence. A 2013 University of Kent study on the impact of Carnage UK gatherings reported increasing moral panic over such excess, and described the growing attention to the “uncivilized body” as “ill-disciplined, grotesque, or unrestrained.”1 The same could be said of the bodies and behaviors in Williams’s work. Ruffles, at the artmonte-carlo 2019 art fair, was an iteration of the aforementioned 2017 Ceremony of the Void, originally performed in London. As with the majority of the artist’s presentations, an elaborate, chimeric installation laid the groundwork for audience immersion. (Furthermore, Ruffles was shown in Monte Carlo’s historic Riva Tunnel, which houses highly coveted and steeply priced race boats.) During the performance, a banquet setting saw veiled, semi-nude female performers cram, throw, smear, and sit upon ornately decorated cakes— the kind one imagines might have been served to Marie Antoinette. The all-female cast is of note, as Williams remarked, “The woman who drinks excessively can seem an ultimate act of transgression, behaving in an unruly and unmediated way which is at odds with socially acceptable representations of the feminine.”

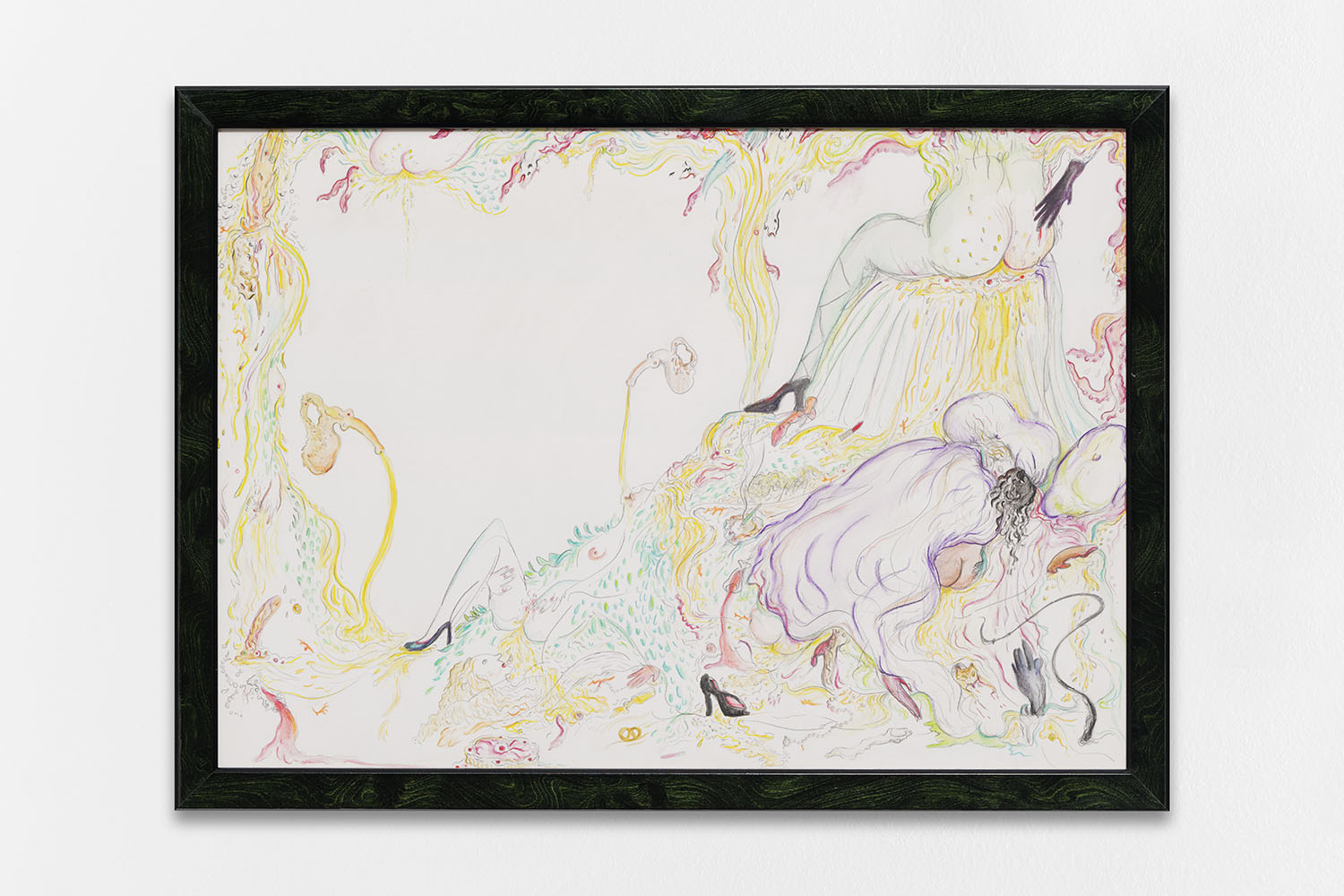

Though the work is contemporary, it also demonstrates Williams’s exploration of behavior that harks back throughout Western history. In discussing Carnage UK, she says, “This carnivalesque behavior also seems to be a mirroring or carrying-on of the traditions of ‘sanctioned’ chaos allowed at carnivals and feast days by the state across Europe in Medieval times.” Other historical references include the obvious Greek and Roman orgies and, as Williams describes, the “Baroque-like” qualities of the performances. Williams also cites interest in the ancient Greek goddess Baubo, who exposed her enlarged genitalia to Demeter as a source of humor during the latter’s mourning over the loss of daughter Persephone to Hades; Baubo’s name also refers to baubon, the ancient Greek term for dildo. (It is worth mentioning that Williams did her Masters dissertation at the Glasgow School of Art on the history of the dildo, further underscoring her ongoing engagement with the histories of objects and behaviors they serve.)

Excess is a tricky word. Like acrobats walking a tightrope, we attempt to maintain a delicate balance between extravagance and self-control, all in order to adhere to societal standards. Williams, on the other hand, rejects this socially constructed definition of civility by directly exploring the act of indulgence. Through her work, she looks at the very human feelings of desire and disgust, thinking “more about the dissolve” between the two “as existing within each other and therefore not always being diametrically opposed (at least on a subconscious level).” As such, one might then consider desire and disgust to be closely aligned cousins on the scale of human emotion, acting as reflections for both our most intimate compulsions as well as what feeds our sense of shame or repulsion.

Shame plays a large role within the scope of Williams’s research. It is no secret that sex has long been associated with shame: “Sexual fantasy is one of the ways we try to undo shame, to reverse our life experiences of shame at the hands of others.”2 Thus, sex is both the source of shame as well as a mode in which one is able to overcome it. This plays out in the artist’s latest exhibition, “Sunday Fantasy,” at Mimosa House in London. The central work, from which the exhibition draws its title, is a new video (produced in collaboration with Amy Gwatkin) surrounding protagonist Veronica Malaise. Played by four different women, including Williams herself, Veronica encounters an ancient, shell-shaped glass bottle, possessed by the spirit of a fictional lesbian priestess from the Roman empire. When used, the object realizes one’s sexual or erotic fantasies. The four actresses are interchangeable, emphasizing that Veronica is a woman that inhabits all of us, despite differing details in our erotic fantasies— be they in the form of eel-like figurations or group massages.

Because the affect and emotion of shame is spurred “any time desire outruns fulfillment,”3 one might consider sexual fantasy as an empowering antidote to the experience of self-loathing. Embracing one’s sexual proclivities might serve to dispel shame, and Veronica reclaims any sense of shame in sexuality through use of the bottle to reach sexual fulfillment. Indeed, this ties into the same theme of excess upon which Williams bases much of her practice. She explains, “Being overwhelmed is a kind of excess— also similar to being overwhelmed in orgasm, say shame after orgasm.” Her 2015 exhibition “Pel,” mounted at Galerie Antoine Levi in Paris, also touched upon similar notions: pel is the Old French diminutive for “skin,” and, per the press release, the video and exhibition were “meant to operate as a troubling texture of sensual experience, conveying a sensuality that is at once voluptuous and tinged with anxiety and a kind of sickness.”

Like Ruffles and Ceremony of the Void, “Sunday Fantasy” and “Pel” also orchestrated an atmospheric installation of sorts: the spaces were transformed into environments with pink lighting, producing a heightened affect, and objects from the video(s) and other ceramic works were on view in both exhibitions. These objects too are a key factor in Williams’s practice. In the “Sunday Fantasy” moving-image work, Veronica discovers the bottle near the mouth of the Thames Estuary; in reality, Williams came across the artifact —a Roman perfume bottle—in the British Museum. Concerned with the manner in which histories of museum artifacts are told from a patriarchal Western viewpoint, the artist aimed to subvert this narrative by imbuing it with the history of the Roman lesbian priestess.

This captivation with objects translates to Williams’s extensive work in ceramics; she describes the process by which they are produced as “performative, meditative, and sensual,” and elaborates on how ceramics can “almost look like bodily fluids, or extensions of the bodies sometimes.” Here, the body again becomes a facet of the artist’s interests, circling back to the excess of the “uncivilized body.” Women have historically been taught to be ashamed of their basic anatomy and sexual organs—over which they have no control—as well as the functions of the body that also cannot be controlled. This begins even before puberty or adulthood with vaginal discharge:

For many girls, the vagina first calls attention to itself by leaking some sort

of discharge. Stained underpants call to mind the shame of urinary dyscontrol […]

With the leakage of fluid also comes odor—thus a woman is subject to both

self-dissmell and self-disgust merely because she is female. These affects,

of course, keep company with shame.4

Regarding fluids, Williams discusses urine in particular, saying, “Bodily fluids are something traditionally related to disgust, but also could be taken as a sacred golden liquid or a fetishized bodily waste item. Then the fetish language somewhat flips this on its head.” (This remark should be taken in consideration of the fact that decanters filled with honey-colored liqueur were among the array of victuals featured in her orgiastic performances.)

The body, then, is arguably at the center of Williams’s investigations, playing a key role in all phases of the process: first through indulgence in sex, substances, food, or myriad other vices, then through repulsion caused by shame. Williams expounds: “I suppose I am thinking more about the compulsion to expose the body or to indulge in the excessive and then the purging or shame of this. There is this kind of hinterland of exchange between abjection and desire that I am interested in capturing.”