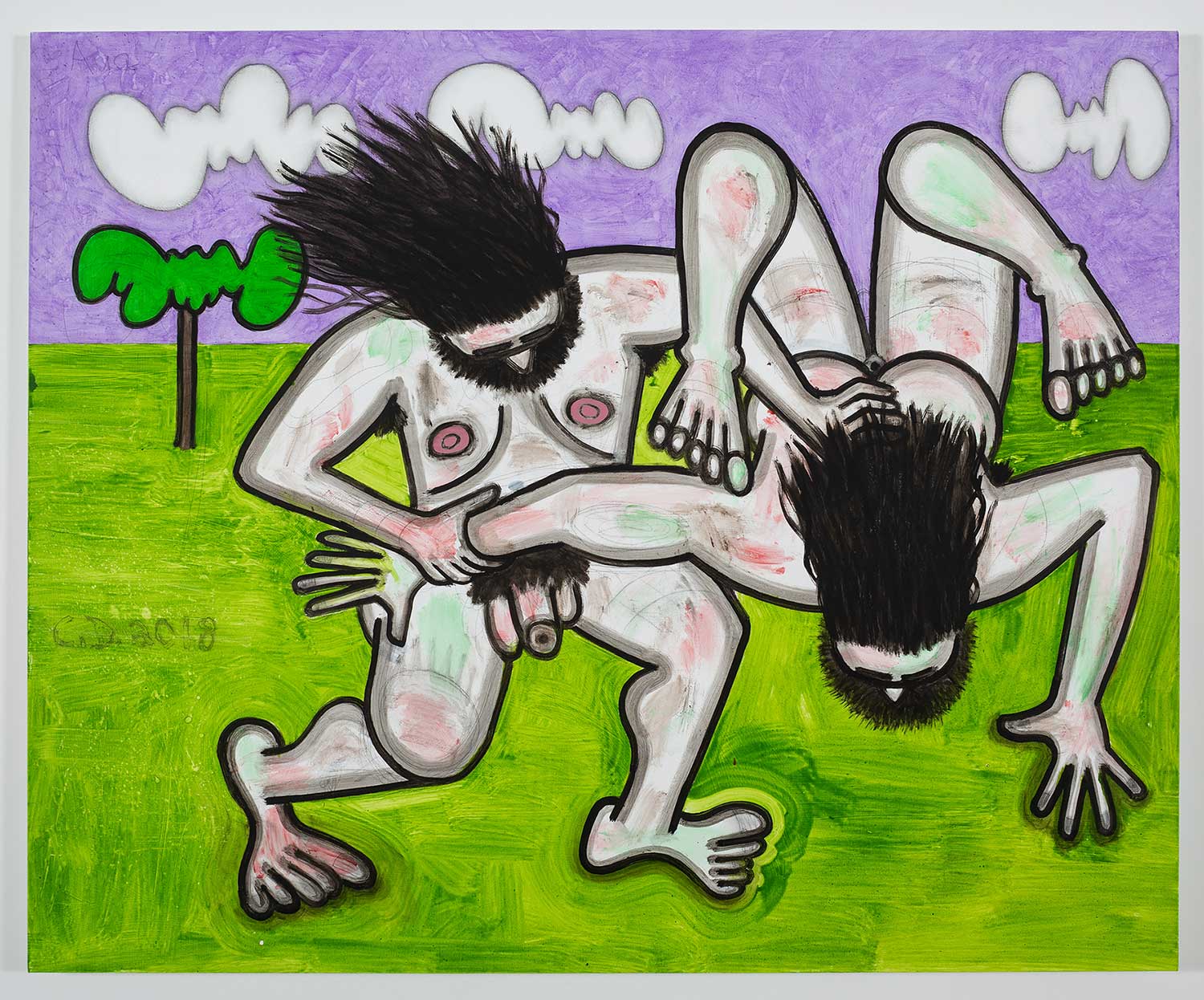

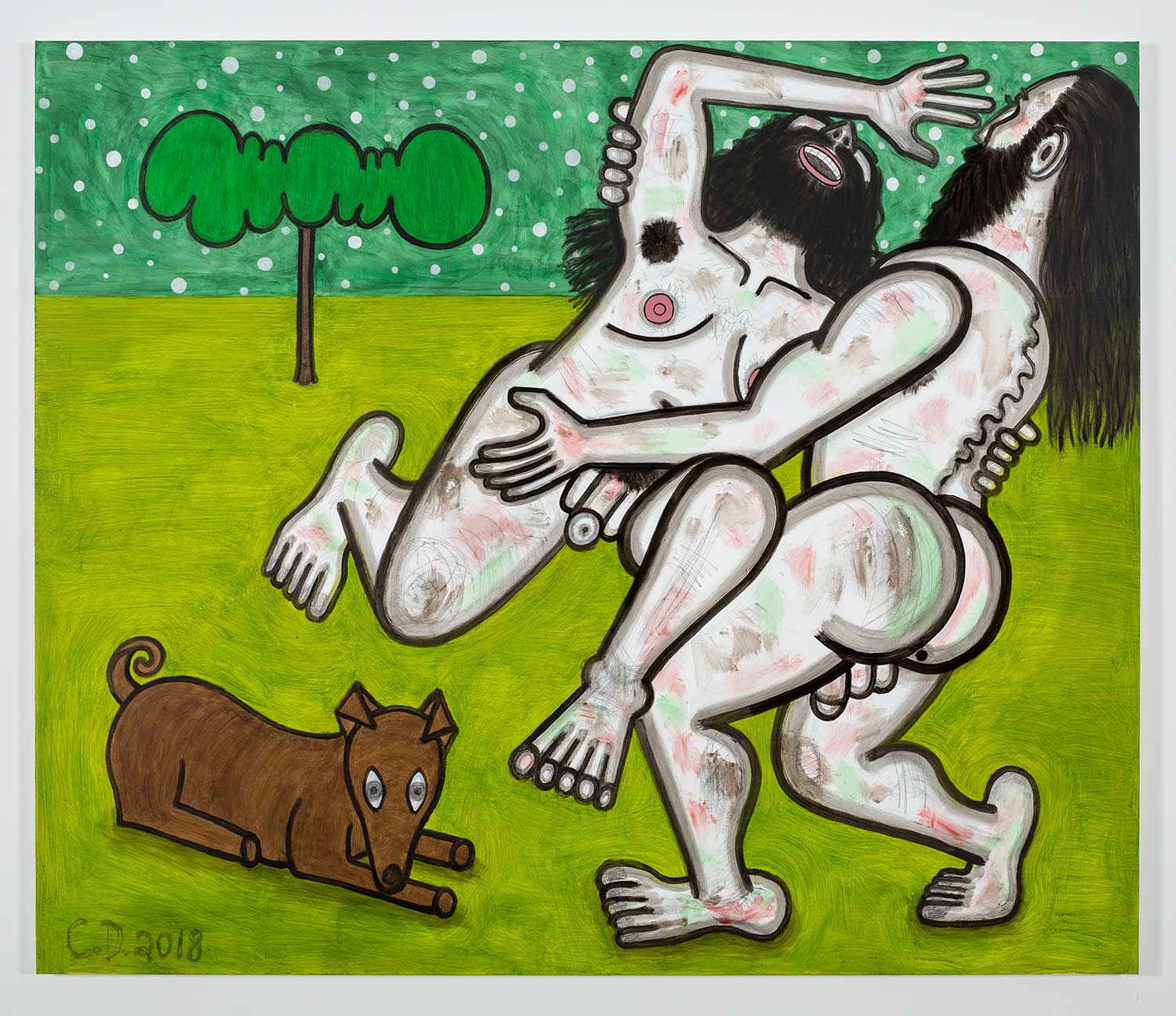

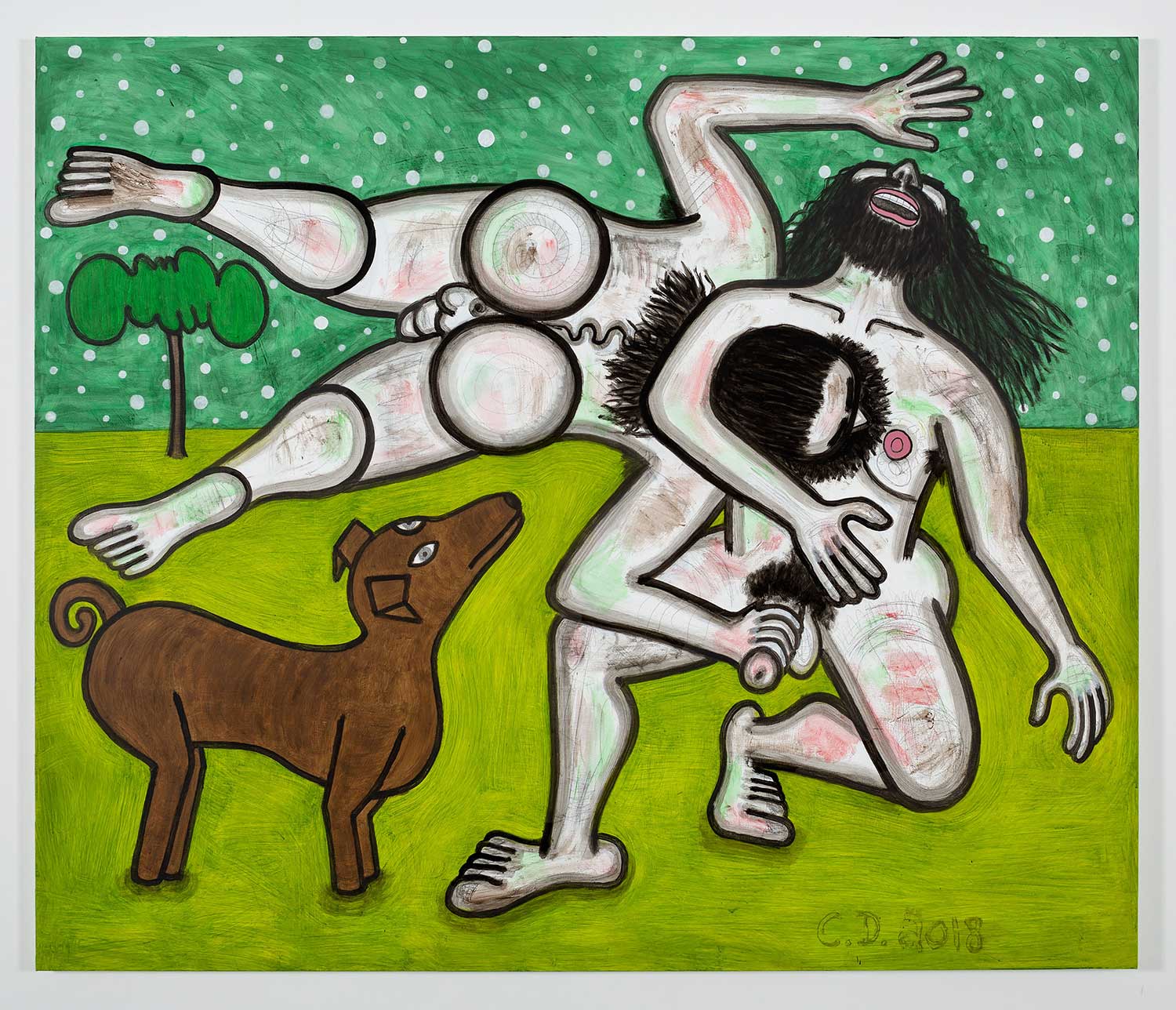

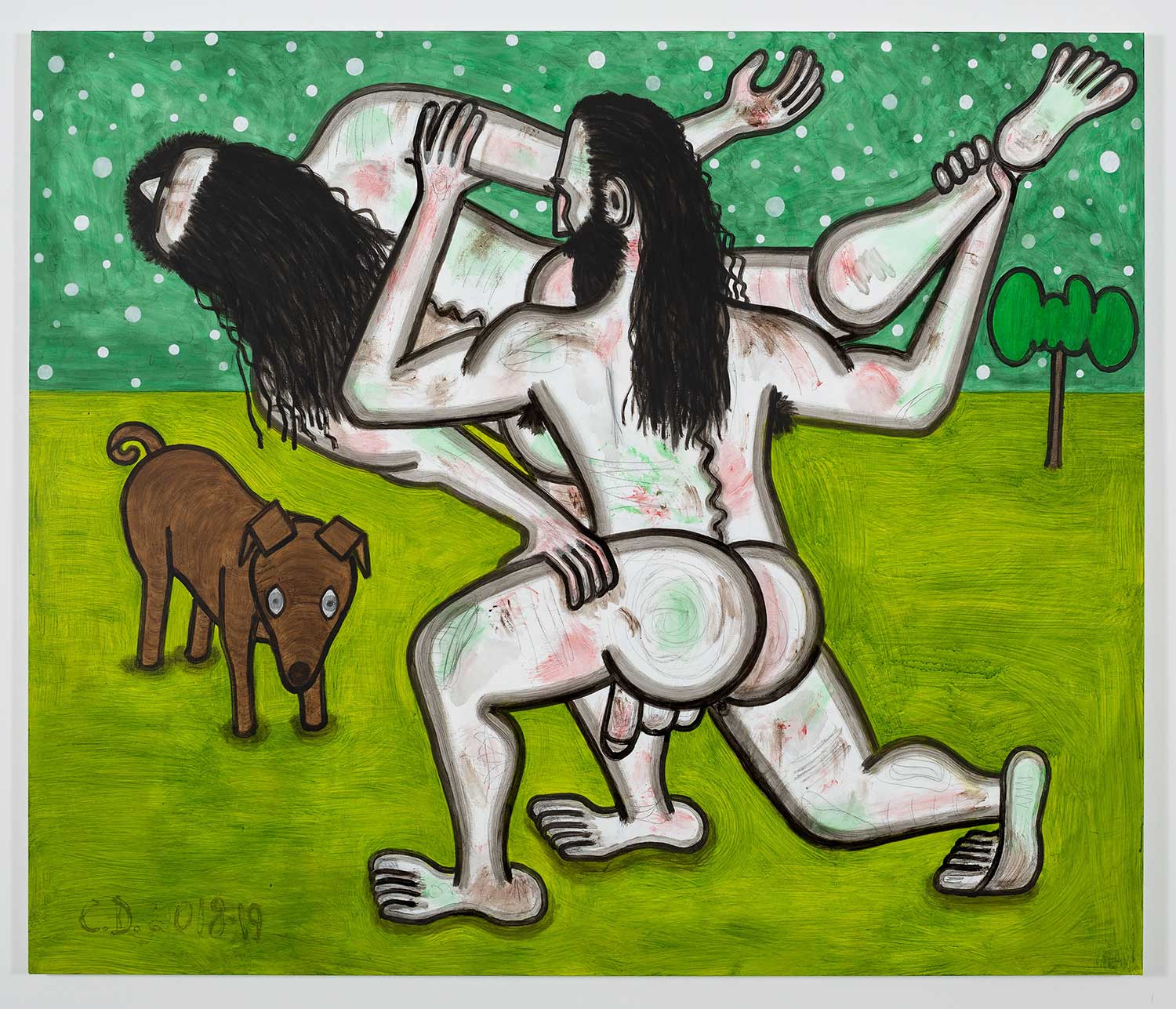

Body parts are also abstract shapes in Carroll Dunham’s “Recent Paintings,” the figure playfully winking at geometry. His mid-scale canvases depict two longhaired men wrestling naked in grassy landscapes and barren scrubland — or perhaps they are dancing, practicing yoga, or are in the midst of tantric eroticism. Their buttocks, heavily outlined in black, are two perfect circles; their nipples, seen from the front, are concentric rings of bubble-gum pink or, from the side, are stacked as little rectangles; anuses and belly buttons are dense black dots; likewise the urinary meatus is akin to a huge dilated pupil. In some paintings the men could be smiling, screaming, or wincing; in others they grab each other mid throw or vinyasa.

Orange Sky (3) (2018–19) sees one man picking up or dropping the other beneath a burning orange sky and pulsing yellow sun. At the center of the composition, testicles and toes combine in a tangle of swollen oblongs. Skin is stained with scrubby brush marks of pink and brown, a mix of bruises and mud alongside finger marks where flesh has been slapped.

The effect leaves us in limbo: these works cannot be pinned down, which feels strangely unnerving. They are neither violent nor sexy; the figuration suggests both abstraction and caricature. Given their cartoonish depiction of flesh, they should somehow be lighthearted or funny. Dunham is known for such semantics: the voluptuous women of his “Bathers” series channel the joie de vivre of Henri Matisse or André Derain — all sun, skin, and sea. Dunham has described the works in this exhibition as “self-aware, somewhat problematized natural history paintings” — problematized denoting, perhaps, the disconnection of the figures from their immediate environment, their self-absorption as the world watches on.

Stranger still, we never see these men’s eyes. Their faces are always turned. The only direct gaze comes from a little brown dog and bat-like creatures in the background, specimens of natural history that seem poised and wise: symbolic soothsayers overseeing this lusty tussle. In one of the show’s two closing paintings, Red Ending (2018), a man straddles the other, his bloodied hands raised, holding two eyes. Are they his or the opponent’s? Are they an animal’s, or even the all-knowing eyes of the sky? And, moreover, have they been fighting or fucking? Unlike Sophocles’s Oedipus, who gouges out his own eyes in despair when the truth of his story emerges (father murdered, mother bedded) — the tale of these two remains ever mysterious. They are at once satirical characters engrossed in their own game and a formal exercise in exaggerating the abstraction that underpins life; a push and pull that perhaps, in the end, tells a lonely tale about mankind’s simple savage strangeness.