The task of representing Finland, Norway, and Sweden — or the Nordic countries — at the 58th International Art Exhibition of the 2019 Venice Biennale has been entrusted to the Museum of Modern Art Kiasma in Helsinki, in collaboration with the Moderna Museet in Stockholm and the Office for Contemporary Art Norway (OCA) in Oslo. “Weather Report: Forecasting Future” is the title chosen by curators Leevi Haapala and Piia Oksanen (director and senior curator of Kiasma, respectively), who aim to address the issues of climate change and shrinking biodiversity through an exhibition of works that draw attention to the interdependence of humanity upon other nonhuman species.

In Finnish, November is marraskuu.

In Finnish folklore, “marras” means one who is dead or dying.

After a short period of below-zero temperatures, the world stops,

when the damp topsoil freezes for a while into an immobile carapace.

—nabbteeri

At the core of the project “Weather Report: Forecasting Future” is an acknowledgment of the harmful effects produced by the current geological era, the Anthropocene, by highlighting how the human body is a holobiont — an assemblage of symbiotic organisms — in contrast to the concept of the individual as a separate unit. In this spirit the entire show is imbued with an open and proactive approach.

The artists chosen to represent the Nordic countries, here presenting newly commissioned works, have already been investigating these themes for many years. They include Norwegian artist Ane Graff (b. 1974), Swedish artist Ingela Ihrman (b. 1985), and the Finnish duo nabbteeri, composed of Janne Nabb (b. 1984) and Maria Teeri (b. 1985).

Trained as painters, Nabb and Teeri started collaborating in 2008. Working as an artist duo, sharing their life and work, they began to reflect upon and ironize the concept of having a combined identity — sometimes in explicit ways, for example with the title of their 2010 show “Artist Couple: Doubling the misery has never been this fun” at GalleriaKONE in Hämeenlinna. This focus was made explicit by the name they chose for themselves and used for years: Nabb + Teeri. Today, however, the twosome has become a single entity — nabbteeri — suggesting something more akin to the world of bacteria than to the ego of the individual subject — a world where male and female are united in androgynous fusion.¹

They were noteworthy participants in the project “Frontiers in Retreat: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Ecology in Contemporary Art” which, from 2013 to 2018, oversaw the cooperation of eight international institutions dedicated to artist residencies. Thanks to interventions such as Sticklikes, completed upon their residency at Viafarini in Milan in 2014 — the same year they were nominated for Finnish Young Artist of the Year — nabbteeri gained recognition from audiences in Italy. Sticklikes, still in the Viafarini collection, is exemplary in its use of recycled material, typically collected from the very gallery space that exhibits the work or from warehouses filled with scraps and discarded packaging. The impoverished, blemished, and provisional aspect is combined with yet another type of reuse: the reworking of past installations and still lifes, often in watercolor or 3-D animation, based on an inventory of objects and images scattered throughout the everyday life of nabbteeri.

The need to bring order to chaos — to observe it, index it, and make it into art — is the subject of Table of Contents (2011) from the Kiasma collection. The work consists of forty-six watercolors and as many audio files that are the result of a long process divided into five separate phases: searching for objects in garages, garbage containers, online auctions, and flea markets; storing these items in plastic, paper, and canvas bags, cardboard boxes, and buckets; planning an inventory of 3496 words; creating watercolor renderings of each container and an audio recording naming all of the objects stored inside; and returning all the found material to the places (or similar places when necessary) from which it was taken.

This meticulous operation of collecting, organizing, cataloguing, creating, and restituting betrays an attitude that is completely at odds with humanity’s current rush toward self-destruction. Rather, their approach advocates a quiet, rejuvenating means of observing the (human and nonhuman) world, almost as a discipline, exactly as suggested by the philosophers Antti Salminen and Tere Vadén in Energy and Experience: An Essay in Nafthology (MCM’, 2015). With these exercises in principle, nabbteeri show us that it is possible to resist the destruction of local realities via the widespread use of nonrenewable energies, practicing instead a transgenerational application of a manner of living and working that they first explored during a 2015 residency in Farrera, in Catalonia, Spain.

This interdependence between life and work, between man and nature, between the organism that is us and the approximately 160 species of bacteria that we host, dissolves boundaries and replaces them with one continuous cycle of creation and destruction. This cycle is clearly evident in the works themselves, which are the result of the interplay between the artists and the things surrounding them, and in the way their combined creative process functions as a state of continuous flux, always in progress. Thingness (2013), at the Poriginal Galleria in Pori, in which nabbteeri were present and worked during the gallery’s opening hours, serves an example of how the duo characteristically break down boundaries. Another example is mesh /mɛʃ/ (2015) at the Areena of the Espoo Museum of Modern Art EMMA, in which the space was filled with material either scavenged from the museum’s warehouse or else brought along by the artists who, in their everyday creating and dismantling of structures, at times blurred the distinction between these two opposing processes.

A topic of increasing interest to nabbteeri is the world of living beings that inhabits our bodies — a world that has been considered separate from ours, if only because it is invisible to the naked eye. Such entities appear in the domestic setting of the 2016 video animation Blind Spot as unassuming, biomorphic forms that are vaguely alien but also disturbingly real, somehow recalling tumor cells. These invertebrate creatures become the visual equivalent of a narrative voice in the longer and more elaborate piece Thinking of Invertebrates, 2017. The work tells a story with a diaristic tone, making minute observations about insects and animals as well as pseudo-apocalyptic animated forms; altogether, it confounds and never satiates the longing for meaning.

There is only the presentation of facts, the mise-en-scène of reality, as in Ethnographies of a homespun spinelessness cult and other neighbourly relations (2019), the title of their intervention created for the Nordic Pavilion in Venice. The work consists of three parts, two of which are found outside of the pavilion: Compost and Dead hedge. The former is placed where a sick tree once grew and has since disappeared; the compost is made with nitrogen-rich plants, organic surplus from the Biennale gardens, and Venetian briccole (wooden structures built along the lagoon for navigation, which are no longer used due to infestations of the mollusk Teredo navalis). The latter, Dead hedge, is an aluminum geodetic sphere that contains fallen branches collected from the surrounding environment, transformed into a habitat for birds and invertebrates that now blocks the passage for visitors in the elevated area behind the pavilion.

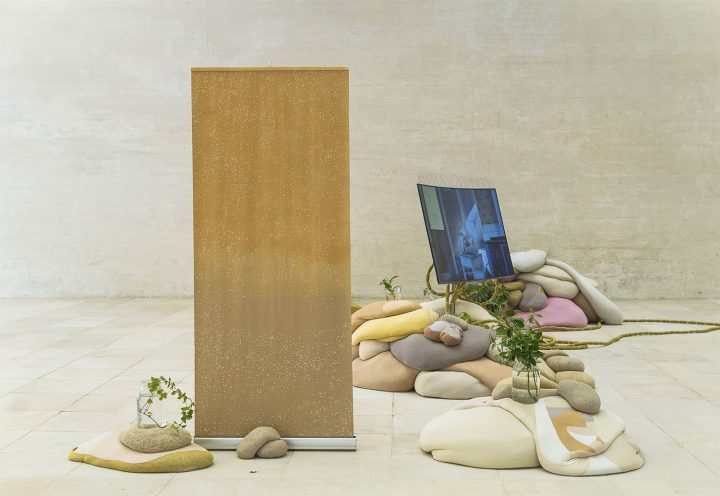

Finally, the interior environment, titled Gingerbread house, is comprised of different elements: a new two-channel video installation; “anti-pigeon spikes” located at eye-level; sandbags, handmade from recycled textiles and filled with Venetian sand that will be returned to the lagoon by local gardeners at the end of the biennial; cuttings of local flowers placed in water; building paper used for air barriers in houses; watercolors depicting wood samples marked by the woodboring beetle Anobium punctatum; and the residual powder of ash trees made by woodworms from nabbteeri’s house. Although these last three elements (in addition to the sandbags) derive from Finland and were carried by the artists on their long and eco-friendly journey to Venice, the other elements were found on location or else arrived via transport from Kiasma.

Ethnographies of a homespun spinelessness cult and other neighbourly relations, like other works by nabbteeri, is “an environment that is to be experienced from the inside and internally rather than admired from a distance.”² Just as a forest or a snowy landscape cannot only be admired from the window of a comfortable, heated apartment, neither can our gaze become so virtual that we can no longer appreciate the porosity of the world. As peculiar spokespersons of neo-materialism³, nabbteeri present us with a tactile view of the microscopic world of invertebrates that they move through constantly, leaving behind an imprint of their work.

These traces cannot be avoided; rather, they are simply observed and rendered visible. After all, it is through an analysis of facts, as British director Adam Curtis aptly suggests, that we can understand who we are and how we are constructed — before subzero temperatures cause everything to lose its color forever.