In his recent sculpture and photographic works, Kayode Ojo ruminates on the contemporaneous nature of consumer desire and social performativity. Small-scale polished items, such as surgical instruments and stainless-steel shaving apparatuses, have been fastidiously organized atop several customized shop display cases, such that their mirror-clad surfaces seem to merge with the chrome-plated objects.

Might the cold, even austere aesthetic of these arrangements intentionally refer to the plot device in the 2002 film Equilibrium — with which Ojo’s show shares it title — predicated on the medicinal suppression of emotions through daily injections of a drug (familiarly) called Prozium? Certainly the ominous looking syringes in I’m Fine (all works 2018) hint at this connection.

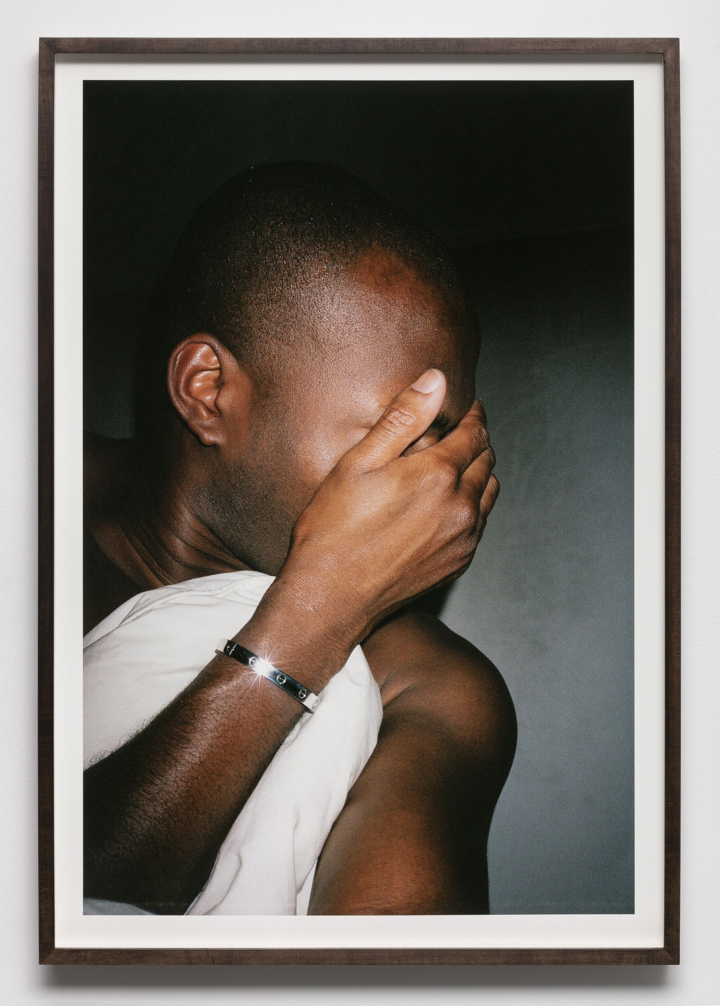

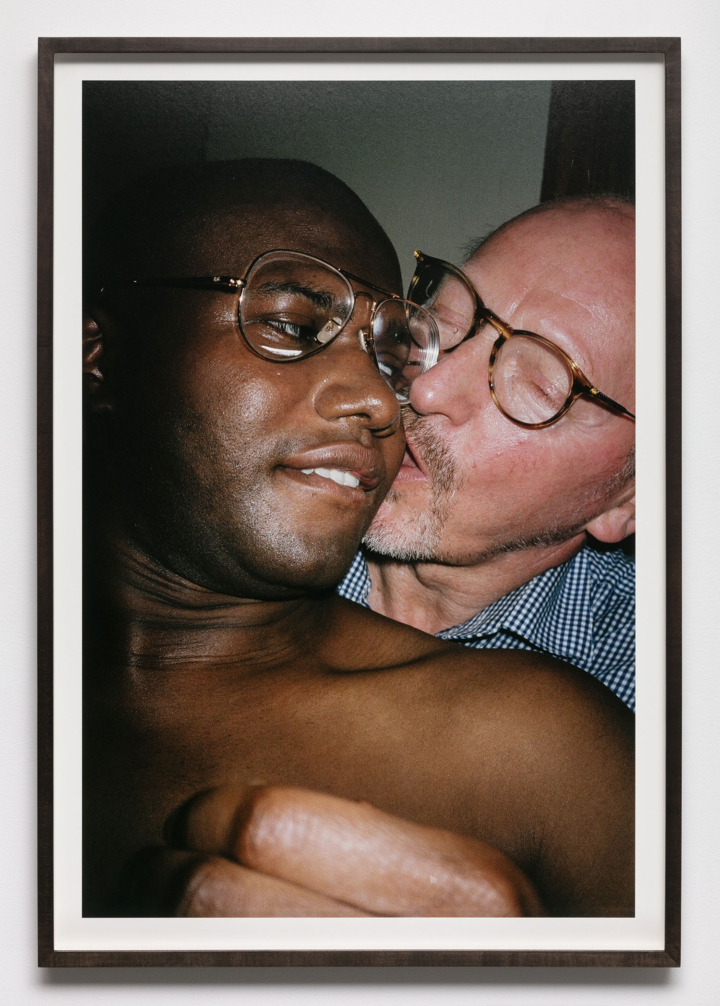

The clinical, dispassionate commerciality of these retail products are shown in close proximity to a series of staged photographs in which the artist’s own body is explicitly subject. In these images, Ojo postures, appears in drag, and yet is hedonistically self-conscious, often shying from the camera. Visual clues can be found between the paired mediums: the artist shields his face in the photograph Scorched Bedroom, Paris (Cartier), while the camera picks up the glint of a Cartier bracelet, a knocked-off version of which appears in Echo (Cartier Love Silver), described in the listed materials as “Men Women Love Fashion Screwdriver Bangle Bracelet.”

By relating the commercialized object with self-portraiture, Ojo equates consumer desire with capitalism’s pursuit of unrequited love and fetishism — further exemplified in A Very Unusual but Very Elegant Gesture, a film loop shown on two back-to-back projection screens in the middle of the space. In it, a Belgian antique dealer caresses a nineteenth-century Nigerian object, enthusing over it with such lines as, “This is a gem of an item.” Ojo’s work speaks to the fetishization of commodity via objectification; for instance, the artist’s photographs more closely echo the stylization of a fashion photo shoot than performance documentation. In this subtle balancing act of assemblage and imagemaking, where does one then place House Call, a serving cart parked in the entrance to the gallery, replete with an antiquated oil lamp and a rectal speculum? Projecting notions of servitude, treatment, and inspection, its presence intentionally disturbs the equilibrium that Ojo has created throughout the rest of this thoughtfully composed show.