A Vogue Idea is a column by Matthew Linde exploring contemporary fashion practice.

As Caroline Evans discussed in her rigorous book “The Mechanical Smile,” the origins of the fashion show reveal a constellation where the body, commerce, and modernity converge. Described as a theater without narrative, fashion’s runway illuminates the paradox of irrational mutability and mechanical standardization.

The “first” runway could be understood as the practice of couturiers sending living mannequins (what we now call models) into the public boulevard sporting new designs, eliciting shock and photographic dissemination. This animation of bodies performing novelty in urban life foregrounded the format we know today: models passing along a strip flanked by their consuming onlookers. Runways express the formaldehyde of a culture in flux. While technological treatments of the runway have modified since its emergence at the turn of the nineteenth century, its underlying edifice has remained largely intact. Despite this ongoing scenographic sameness, various designers have explored the runway as a discursive site to interrogate the mechanics of fashion’s circulation. These runway experiments reconfigure the relations between audiences, arrangements of space, the carnivalesque body and the haunting of its commodity form. Leaping from Paul Poiret’s epic 1911 “A Thousand and Second Night,” the designers exhibited at Kunsthalle Bern have approached the runway-as-medium to extend and challenge ideas within their own practice as well as the fashion system at large.

Passageways curates videos of runway shows by designers that have reimagined the catwalk as an exploratory performative tool to produce fashion. Also exhibited are outfits by some of those fashion designers alongside a series of commissioned replicas that rewrite new histories of the runway as a suspension of fashion-time.

BLESS, N°0-4, Alexanderplatz, 1998

Commissioned for the Berlin Biennale, Desiree Heiss and Ines Kaag of BLESS staged a “living commercial” in Berlin’s large public square, Alexanderplatz. Everyday people as models walked past an inconspicuous CCTV camera wearing pieces from collections N°0-4.

BLESS, N°25, Uniseasoners – Life vs. Consumption, 2005

For N°25, Uniseasoners – Life vs. Consumption guests were invited to a restaurant on rue Portefoin, Paris, to enjoy a light meal served by waiters wearing their latest collection. In a convivial and discursive setting, the waiter-models explained the pieces they were wearing to their guests, foregrounding the relational and everyday codes of their clothing.

BLESS, N°32, Frustverderber, 2007

Taking the form of a soccer match, BLESS left the show’s unraveling completely up to chance. Friends were invited to take part, some more active than others. Delicate objects were placed in one goal, and whether or not these would be hit and subsequently broken was not choreographed or planned.

Helmut Lang, Séance de Travail FW93/94, 1993

“I called the presentations seances de travail instead of fashion shows, as I really wanted to stress another reality on the runway and also allow myself to sometimes transfer an element from one show to the next, leading to something new in a more elaborate manner. The séance de travail concept made sense to me, as it was set up for the press, buyers, and other attendees. I introduced it by eliminating the elevated runway, promoting all age groups of models, supermodels, and friends, sending them on a ground-level runway that, rather than being center stage, had a square-shaped path with two extensions and different exits. This allowed a fast and interactive flow similar to a public space, where some models rotated one time and others walked the circuit two or three times. It was always at random and a decision I took the second I sent them out. I consider these sessions as performances because I did not only want to convey modern clothes, but also a feeling and mood of a moment in time, which, in combination with men, women, speed, and the unpredictable synergy, created a different dimension for most spectators. I consider this approach a countermovement to posing, and the press in a way defined the events at Rue des Commines as cult-like events (for lack of a better word).” — Helmut Lang quoted in Not in Fashion: Photography and Fashion in the 90s, 2011

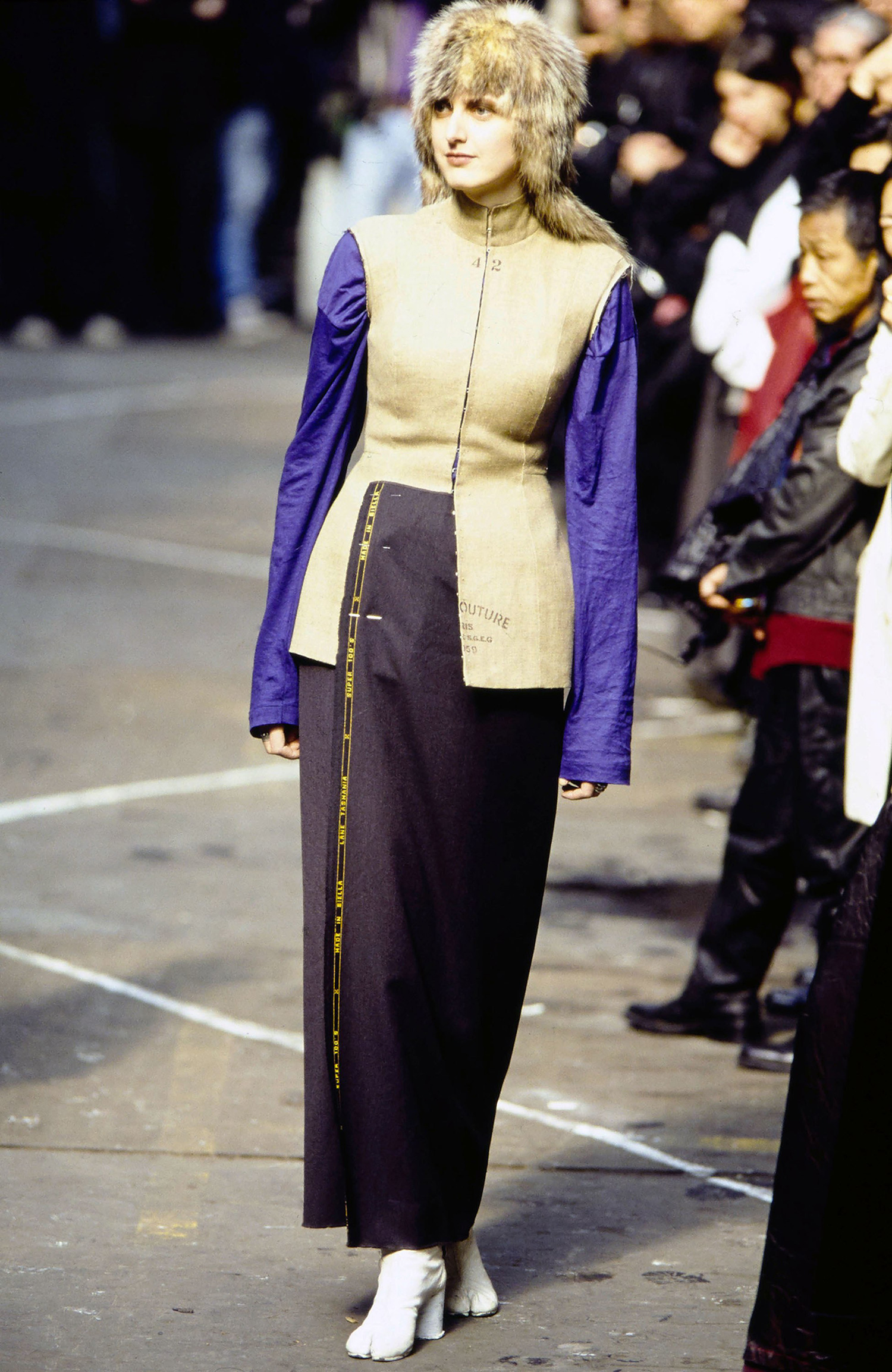

Maison Martin Margiela, FW97/98, 1997

“For his Autumn-Winter 1997–78 collection, free promotional maps of Paris with three locations and times for the show were sent to journalists, many of whom threw them out, thinking they were junk mail rather than fashion show invitations. At 05.00 hours on the morning of the show, a bus carrying thirty-five brass band players left Brussels for Paris where it met another bus that carried thirty-five models to their first destination. This was an abandoned covered market, La Java, at Belville, at 10.30 hours. The second, at 11.45 hours, was a glass-covered loading bay of the huge Le Gibus building at Republique. The third, at 15.00 hours, was a 1930s dance school, Le Menagerie de Jerre, at Parmentier. At each venue the audience watched the models and band get out and then followed them into the show space as the band played a slow march. At the third, however, instead of going into the building the models simply paraded through the streets mingling with the public. They were accompanied throughout by Margiela’s assistants clad in white laboratory coats, a tradition borrowed from the couture ateliers. By departing from his pre-planned itinerary and allowing his models to ‘drift’ through the city streets rather than model on the more conventional catwalk, Margiela evoked two related tropes from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: the flux of the crowd that was central to Baudelaire’s city imagery and the Situationist concept of dérive.” — Caroline Evans, Fashion at the Edge, 2005

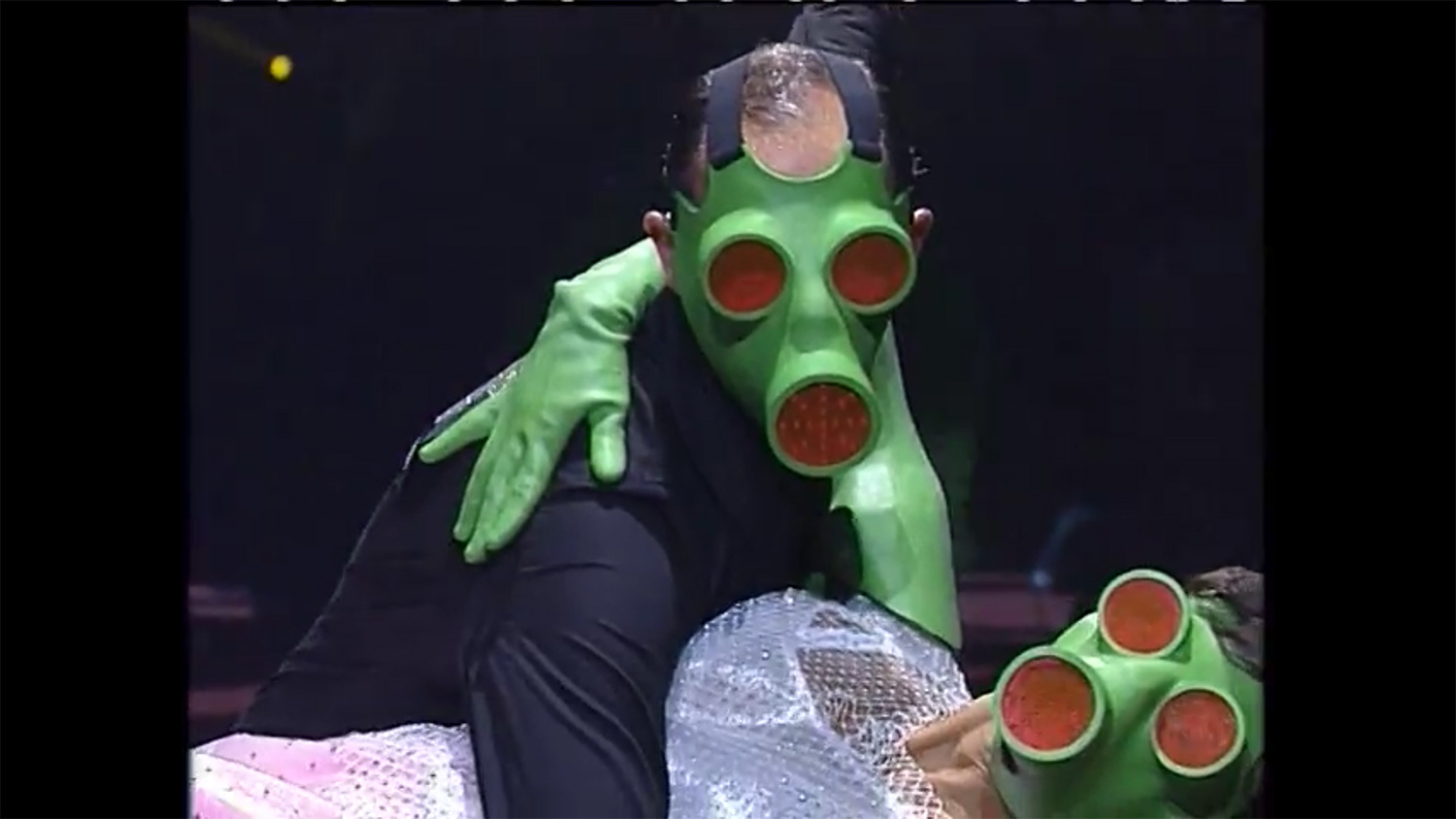

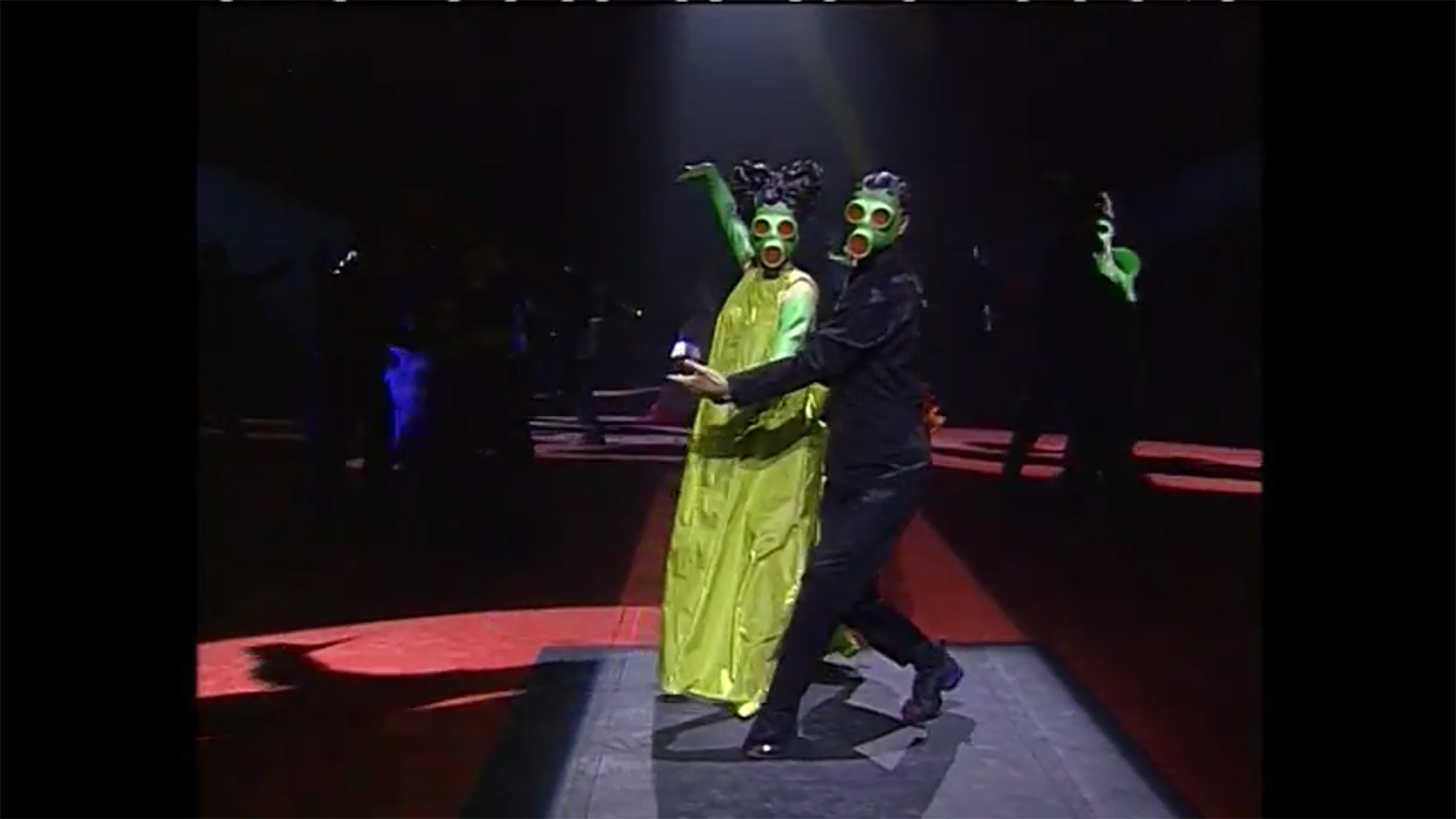

Walter van Beirendonck, W< SS98, 1997

This show, titled “A Fetish for Beauty,” explored the carnivalesque nature of gender roles, commencing with a humorously camp male line dance and ending with a dystopic re-imagining of a 1950s ball.

writtenafterwards, SS18, 2017

The two runways exhibited by writtenafterwards use the runway for narrative storytelling more than showcasing discrete collections. In these lengthy shows, makeshift props and ad hoc costumes are used in performances orchestrated by acts. The designer, Yoshikazu Yamagata, also runs an alternative open-ended fashion school, Coconogacco, which, similar to these runways, focuses on fashion as an expression for performance.