A Vogue Idea is a column by Matthew Linde exploring contemporary fashion practice.

Last year the Parsons MFA Fashion Design and Society program withdrew from the Business of Fashion’s Global School Fashion Rankings. They sited conflicts of interest, namely its combative commodification of education, BoF’s dubious initiation of their own online courses, and the ranking’s lack of geopolitical and socioeconomic variables. And yet ranking is perfectly reasonable in a world where universities are increasingly public-relations businesses.

London’s Central Saint Martins, arguably the world’s top fashion university, consistently produces impressive MA showcases. This year, two graduate collections in particular sparked intense interest: Liam Johnson and Edwin Mohney. While it’s an easy, if not lazy, task to buttress the already elite-ranked institution, I was gripped by the two designer’s distinctive approaches in reimagining the application of dress through reduction and the found object. They were also, maybe for those reasons, the bookends of the graduate runway.

Liam: The idea for the collection was to create a graphic statement with an emotional reaction. It was about reducing or exaggerating the line of the body to create direct vision. I approached this by using primary geometric shapes as the starting point. It’s about trying to capture a fleeting moment and most importantly offering a new visual language.

Matthew: I thought this “reduction” in your work was mesmerizing. It reminded me of Adolf Loos’s Ornament and Crime in how you were framing the body entirely through severe primary shapes. I doubt Loos would have approved of your collection, but it was certainly modernist in its mathematical approach to silhouette. Did your pieces using the spectacular transparent ductile fabric require much toiling to achieve those lines? The precision is vivid.

Liam: I can’t say Loos was a huge inspiration, but it’s funny that you made that connection. I guess it’s a kind of paradox, the conflict of something looking so clean and functional yet being totally unrealistic. The pieces themselves took a while to create. A lot of toiling was involved to get the right tension, because no stretch fabric was the same. Everything had to be created from the final fabric. Everything needed to be pitched and balanced, working with the drape of the fabric to find that middle point between the stretch and the tension. There are also other factors involved such as height. All the hoops where custom made, and things wouldn’t be able to be toiled in till last minute. I reprinted and remade the final dress twice, two days before the show, because a seam was twisted. It needed to be as pristine as possible.

Matthew: This idea of effacing excess was discussed a lot in modernist architecture in that it cleansed forms of representation. As a strange inversion you used the “smooth object” as a type of ornament when you had some models simply holding these large geometric forms in front of them. Reading your work through the flat runway image, I thought these modernist architectural shapes were almost a new form of dress, “attached” only via the wearer’s grasp.

Liam: The shapes symbolize baggage. Yes, they were very primary and very flat, but they needed to be harsh. The idea to have them carried was something I came up with early on, and originally I had five more in the collection. I liked the way they felt strong and confrontational, almost like huge boulders, yet had this contradicting factor — you could hide behind these shapes. The idea for this was never meant to be a new way of dress. It was about saying: This is what I am carrying! This is how I feel! All that was conveyed through scale, color, and texture. They look flat on images but they have a very specific fuzzy texture in reality. The triangle was made of linen. This was important, as it needed to feel like dead space amid the sharp colors. It needed to feel older and yet just as clean, almost ancient.

Matthew: Can you explain the prints?

Liam: I had created about twenty posters of different gradients, colors, and compositions. I created them as a response to some music I was creating at the time. I liked this idea of them feeling like a series of spiritual posters, the way an album cover says everything about the album before you listen to it and sometimes nothing at all. For me, they hold some familiar quality, be it a hazed zebra, skulls, something nuclear, or a saturated colorful spot. I find it hard to articulate the journey of finding all of this, as it hasn’t been a very liner journey at all. It somehow is a romanticized personal manifestation of things, situations, and characters in my life that I love, hate, admire, and find challenging. The main thing that I try to convey in the work and challenge people with is honesty and unknown familiarity.

Edwin: The collection was inspired by my own angst for the seriousness of fashion. I can’t stand the thought of taking a hem or sleeve too seriously. I take craftsmanship very seriously, but the aesthetic value of tradition places meaning in something I don’t measure. I take a more nihilistic approach to my work. To measure something in terms of nihilism is to give it less value, using craft to justify something flippant.

Further, fashion often demands the representation of commercial success as its context. I was interested in creating a late-capitalist representation of fashion through the integration of failing structures and outdated tastes. The collection is based in couture, the most unprofitable sector of the fashion industry, and is incredibly focused on craft but through the use of readymades. Can Duchamp be fashion? This is what I’m interested in.

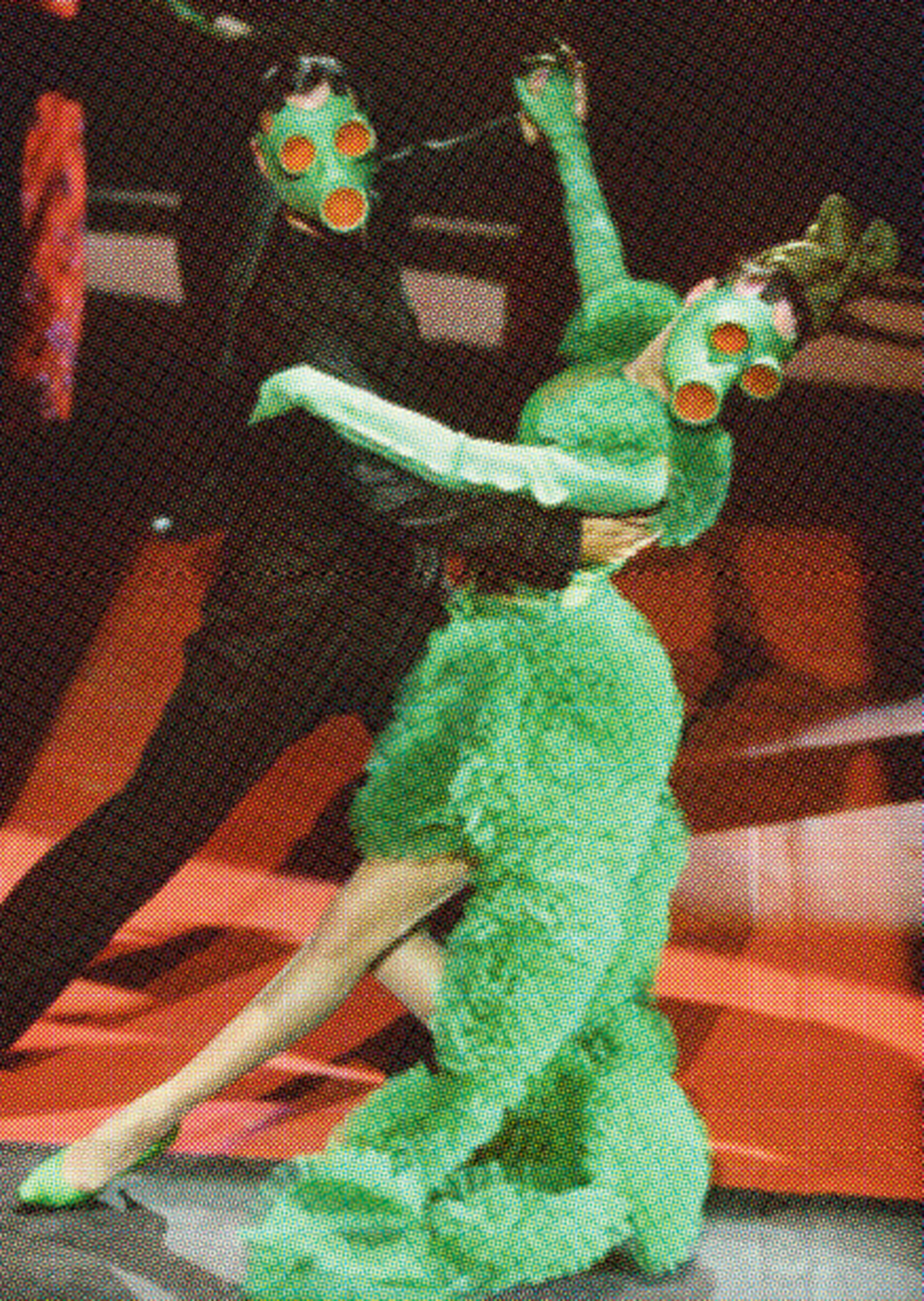

Aesthetically, the only thread through the collection was to balance colors which were taken from products that represented freshness. For example, Evian water bottles and tide pods. This was used to counter the staleness of old-fashioned couture shapes.

Matthew: Right, I like your take on nihilism as value reversal. I would also agree that craft is historically specific. Coco Chanel reportedly spent hours laboring over the exactitude of a sleeve head — it can be funny to think sometimes how this affected, highfalutin gesture is insisted upon as virtuosity. Then again, why not vindicate the absurd? Couture is often encountered on the red carpet. Do you have a favourite outfit from the collection you would like seen there?

Edwin: Yes! I completely agree. Laboring over a sleeve head is futile in comparison to open-heart surgery, but I enjoy the idea that the consumer is paying for that attention to detail with every stitch. It points to clothing as objects of beauty. I appreciate someone’s persistence in their vision of beauty if that is incredibly pristine or an absurd conundrum.

Specifically, I would love the see the simple white ruffle dress with red socks on the runway. I would die to see the chicken sister dresses be worn, but that simple dress maintains a real sense of being a cocktail dress while being just a ruffled piece of fabric. I would like to think that piece would really ride the line between the red carpet best and worst dressed — depending on the accessories of course.

Matthew: “Represented freshness” could be a great WGSN trend report on the color palette of late capitalism. It also explains the alienation of some of your outfits. I found the tandem outfits worn by the Maybury sisters the most eerie — they somehow felt more plastic than the polyurethane of the pool. What drew you to pools as fashion objects? Did you work with other bought readymades?

Edwin: Thank you! It’s something I’ve become obsessed with. Shampoo bottles, water bottles, detergents — the colors are so yummy. The pool was born out of that same obsession. I loved the color of the blue vinyl and the matte white. The pool evolved from the air mattress skirt worn underneath the mountain look. I was making understructures that would function as crinolines, but through a late-capitalist lens. I played with balloons for a long time to build volume underneath fabric. The pool was a natural progression, and I loved how impossible the idea of having a pool on a runway felt. The intention wasn’t to invoke any specific meaning other than creating a moment that focused on expectation and form.

Matthew: One of the reasons why I was so drawn to Liam and yourself is how you both speculated new concepts for the application of dress. In many ways, our imagination of fashion is still constrained by nineteenth-century industrial technologies. Until we have malleable, advanced, user-friendly 3-D printing or virtual reality, where clothes can essentially be sprayed on as readymades, we’re liable to particular hierarchies of “wearability.” You’ve worked a lot with tape in previous work, as well as in your MA collection, which is an exciting proposal for sculpting or assembling dress. Could you explain the process of making these taped fashions?

Edwin: The taped pieces are casts. I wrap objects/people and then reinforce the pieces with more tape from the inside. The casting of an object/person represents an imagined outfit or form that surrounds the body, which is then worn on another person. It came from a question of how can you wear someone else?