Liberty means different things to different people.

I have never liked lying in bed in the morning.

Law did.

My mother does. [1]

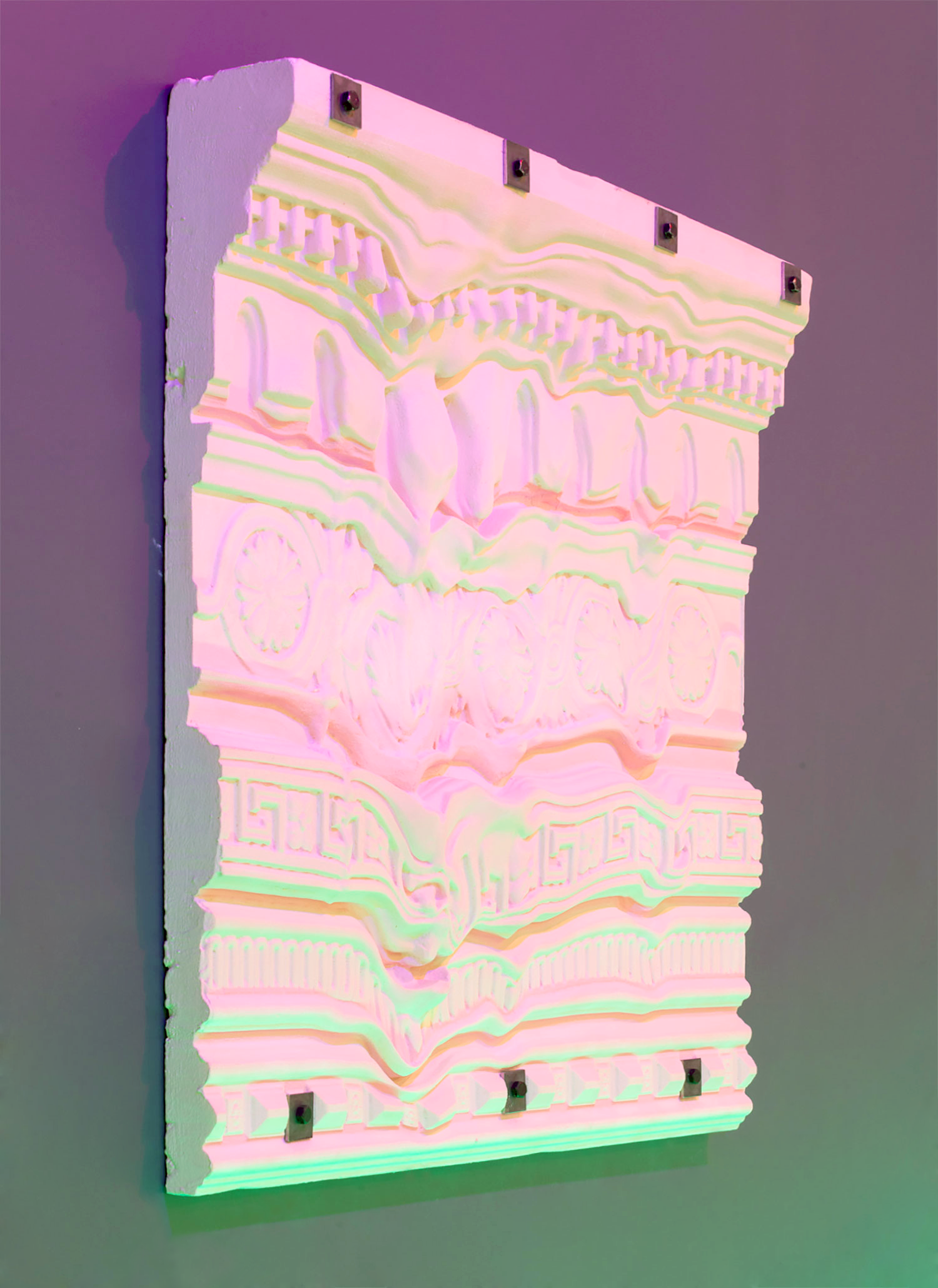

George tells me in a letter that the beds he makes make a rhythm of recesses, and that they set a tempo to work with. That during one summer spent in a grad-school induced June gloom reading novels like Madame Bovary, Two Serious Ladies, Wuthering Heights, i.e., stories about those who abscond between the sheets when shit gets real, he started to appreciate the bed as a site for self-actualization. The idea, or the dream, was that the perspectives of the sprawled-out and the horizontal, the half-dressed and the lethargic could be productive ones, as the pressures of participation — be they from colonialism thinly veiled as tourism, capitalism as sex and shopping, or more plainly art as a “scene” — are done away with. What is left is time, lots of time, to do like James Schuyler might and sit, stare blankly at stuff, and step inside that space of boredom and deadness to prod at it and find its form. Or at least vicissitudes of form, form’s pastimes. “I started to make these beds, one per day,” George writes to me, “because I needed something to ‘realize.’”

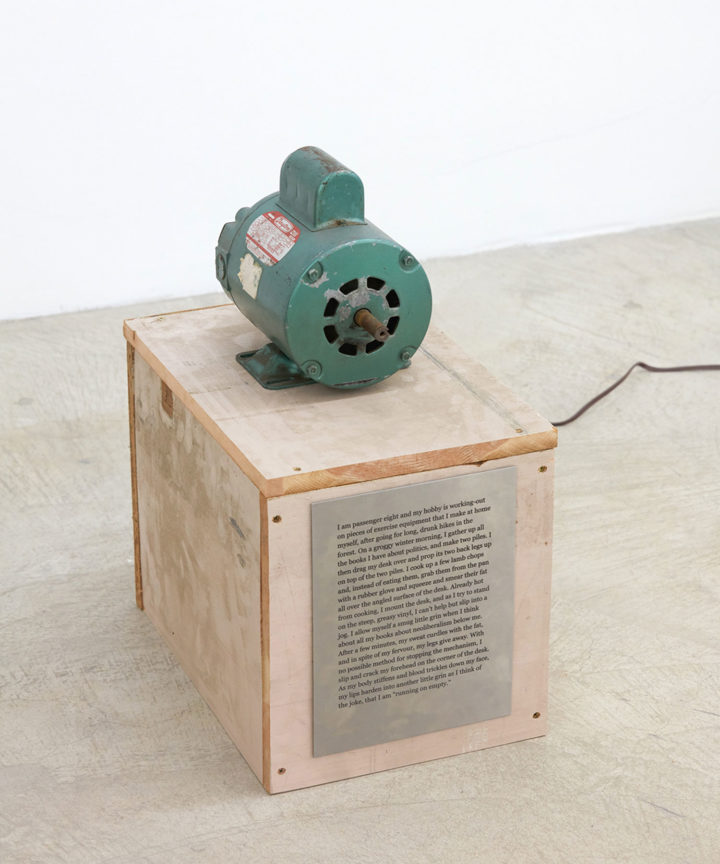

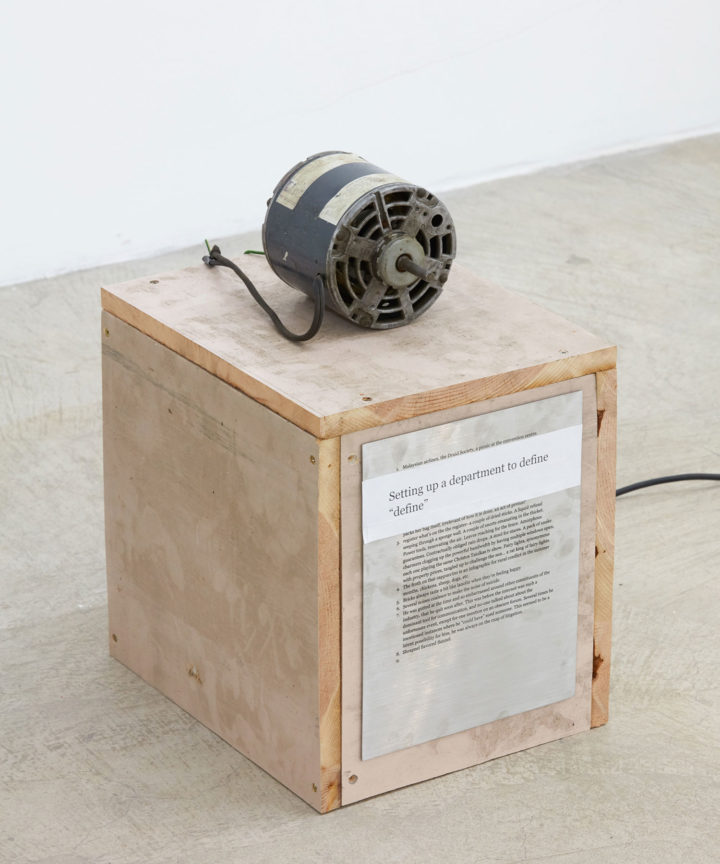

George’s exhibition at Chateau Shatto, “English,” might be about language, and how it foams, like all things redundant. That would certainly be the easy way to read the rote groan of motors in the space, running on empty, unattached to anything useful except maybe conceptually the William Carlos Williams dictum that “a poem is a machine made of words.” But nahhh. If the brain’s word-machine is invoked in these, or anywhere in the exhibition, it is to signal some systemic breakdown. (Getting in bed, staying in bed.) The motors sit atop cardboard plinths, each “labeled” with a copper plaque respectively etched with invoices, one-liners, and flash fiction. Here, language slurs like speech in a dream, or like it might after three martinis and some ketamine taken for calm, or the sake of composition. Instead of asking to be interpreted, the words become bodies, with weights and measures, a materiality. The trick is to treat the purring sounds and concrete poetry as proportionate to the other textures present in the exhibition, understanding that it all fits, as one plaque reads, “somewhere between a kōan and a groan.”

In the grō-an, if I may, the body is recuperated, but also its waste. The language of George’s materials is excess, surplus, spill. The bright fuchsia foam that spouts out of a Rube Goldberg-esque machine into a fun and toxic kiddie pool, the dog poop wedged into framed photographs of sweet-snouted truffle pigs, and the beds, the rote hum, all have in common the featherweight feeling of total precariousness. Anecdotes like being in bed too long, all summer, or taking equanimous, drunk walks through a forest to sober up before going home, or working as a garbage man in the zenith of your sexuality; all dredge up the glut of youth and its laconic, irreverent, and maybe poetic acts. George’s “English” is a paradox between dredging up, say, the scent of sex from the earth and having its association come back to you through the whiff of dog shit. This movement is a game in which nothing imitates or represents “life,” but points to where words resemble things, sculptures read like verse.