In 1967 Germano Celant observed how Luciano Fabro (1936–2007) “reproposes the rediscovery of a pavement, a corner, or the axis that unites the floor and ceiling of a room. He’s not worried about satisfying the system, and intends instead to disembowel it.”

In their elegant austerity, these early works explain why the artist required a separate stanza of the Arte Povera manifesto. Instead of attempting to expose the prevailing aesthetic structure through poverty of materials, Fabro sought to pare down the intellectual scaffolding with which the viewer approached works of art.

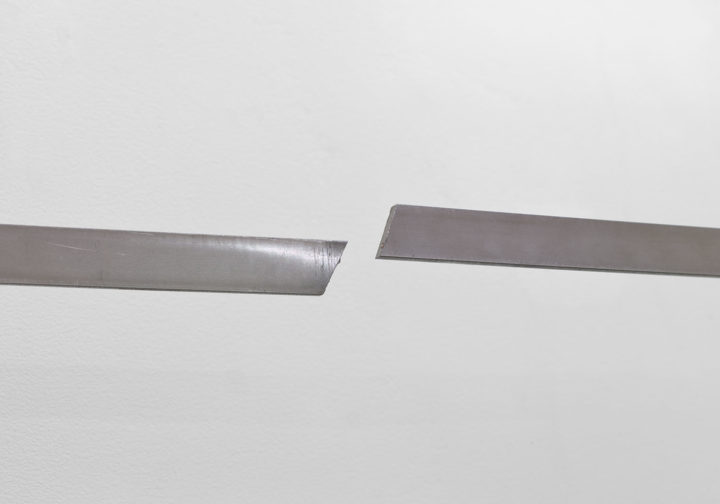

All of the pieces here use metal or glass to dislocate the situation in which they are encountered, both by the body and by the eye. Exposing their surrounding spatial — and therefore institutional — limitations, works such as Croce (1965–2001), a large stainless steel cross, and Asta (1965–2001), whose pole hangs from ceiling to just above the floor, blocking an exit, occupy as much space as possible with the minimum material necessary. Visitor throughflow is routed via a series of works: Tondo e rettangolo (1964–2004), Mezzo specchiato mezzo trasparente and Tutto trasparente (both 1965–2007), and Buco (1963-2005), partitions of cold metal, glass and mirror whose clinical designs target the gallery as a transparently corporate entity — all white walls and potted plants — in a prescient reflection on our own late-capitalist reality.

Other, more playful constructions seem nonetheless to be stress testing the space. Mounted to the wall at one end, Ruota (1964–2001) and Squadra (1965–2001) flex and bend under gravity’s weight, in so doing softening the sculptures’ hard design in a way that reflects the artist’s historical role as a bridge between developments in Italy and post-Minimalist narratives abroad. As the artist once proclaimed: “I need to know how my hands function on something which remains static. The form of Italy is static, immobile, I measure my hands’ mobility against its stillness.” Fifty years on from the manifesto, Fabro’s original scenography reveals the immobility of our fabricated selves.