Il Collezionista is a column curated by Gea Politi and Giulia Gregnanin. Structured around a series of interviews with crucial figures in Italian collecting, the column surveys the attitudes, tastes and outlooks that have shaped a wide range of unique collections.

Giulia Gregnanin: You’ve stated on various occasions that art was a refuge for you, a free zone in which you could get away from the stress of work challenges. Does it still fulfill that need for you?

Giuseppe Iannaccone: I have to be honest: art played a crucial role when I was a young lawyer. At the time, I was entrusted with certain very important cases, but I was just a young man without a mentor. And in that context art was my soul’s “crutch.” I can’t say as much anymore: my work has given me a lot of rewards, and economic balance. But art is still a complement to my personality; art is me, it’s what I’m like. Now I couldn’t recognize my life without it.

GG: How was your collection born?

GI: I think it was the result of a chain of events. At first, I was a young man with a passion for art but without the financial means to collect it. I used to buy lots of art history books; at the Hoepli bookstore there were these enormous shelves that just drew me in. That led me to study art and art history. Then I fell in love with the interwar period and that whole group of artists, who were so spontaneous, direct, warm, emotional, passionate. I felt like I’d found myself. So when I had the possibility to collect, I started with them; I liked to think that one day I would put together a collection that included at least some of these artists. I thought, maybe I could have ten. Then things went differently, and today there’s ninety-seven of them, collected as though they were a single work.

Gea Politi: In 1989 you bought your first work, Sirena Ferita (1987) by Claudio Bonichi. I’d like to know more about that experience.

GI: I would have started collecting sooner. I started off young as a lawyer but had the luck to be assigned some very important cases. When I was twenty-seven I opened my own firm and got married. So my first concern was to buy a place to live, and after that I started collecting, in accordance with my means. After which my work graced me and I was able to devote more and more attention to my passions.

GP: You seem very tied to Milan.

GI: Very much so. I dedicated my first book to Milan, because the city has given me much more than I deserved; a non-Milanese person like me could understand that better. Milan helped me, it never caused me any problems. How could I not be grateful to it?

GG: “Italia 1920–1945. Una nuova figurazione e il racconto del sé,” which took place at the Triennale last February, was the first public exhibition of your collection of works dating between 1920 and 1945. It wasn’t just a show but a truly scientific undertaking, a study of a history that has never been deeply explored and perhaps not even widely collected.

GI: In the interview for the catalogue, Alberto Salvadori paid me a big compliment, saying: “Nobody’s ever told this story, the museums haven’t told it, other collectors haven’t told it.” But it’s a true story and I’m proud to have told it. It’s a story that has to stay intact, so that it can be available to people who want to reflect on the artistic reality of our country in those years.

GP: You’ve mentioned several times that you don’t collect Sironi or Casorati. How come they’re part of this story?

GI: I greatly admire Sironi, Casorati, Morandi and the Italian artists of the twentieth century, and of the Magical Realism period, and whenever there’s an opportunity to see them in a museum I jump at it. But it’s one thing to love art history and to love an artist, and another thing to buy them. I buy what resembles me, and Sironi doesn’t. What he dealt with doesn’t correspond to what was going on in the country. For me art is freedom! My artists don’t have limits; they looked to Europe, they had freedom of color. I wanted to tell a different story.

GP: The Tracey Emin piece you own (I’ve Got It All, 2000) is one of the artist’s most important works. That image helped initiate Emin into the art world.

GI: Buying that piece was a stroke of luck. I won it at an auction; there it’s a matter of seconds. You see, I subscribe to all of the contemporary art auction catalogues in the world. I look through all of them, from the first to the last, and when I see a piece that wins me over I don’t let it get away. The only limit is your buying capacity, but if you have the possibility then you have to take the work home. You said something very important when you mentioned Emin’s initiation. I am, in fact, very attentive to the early phase of an artist’s work, because the poetic inspiration that they have at the beginning usually isn’t comparable to what comes later.

GP: And what do you think of contemporary painting?

GI: Various critics have declared that “painting is over, out with painting.” In my view, painting is the history of art. It’s obvious that whoever paints today exposes themselves to more criticism, because it’s easier to make something that’s already been seen and difficult, instead of adding a new page to art history. But obviously there are people who manage it anyway, and who are admirable precisely because despite using a traditional method they’re able to innovate and make new poetry. Women in particular. There are a lot of things that pertain to the female gender that have never been said and that art history has never dealt with. For example, Wangechi Mutu makes work that’s completely unprecedented. I have a portrait of hers that’s an absolute masterpiece. Everyone in art history has made portraits, so how do you make a revolutionary one? Well, Wangechi Mutu did it. That means painting will never end.

GP: Do you buy a lot at auctions?

GI: No, it’s not my priority. I prefer to buy in galleries, so as to forge a solid relationship with the gallerists. When I started my collection I had some trouble with that, because the gallerists who represent highly valued young artists tend to place them within the best collections. One thing I can tell you is that I’d never be a gallerist.

GP: Have you been realizing projects that involve young artists for a long time?

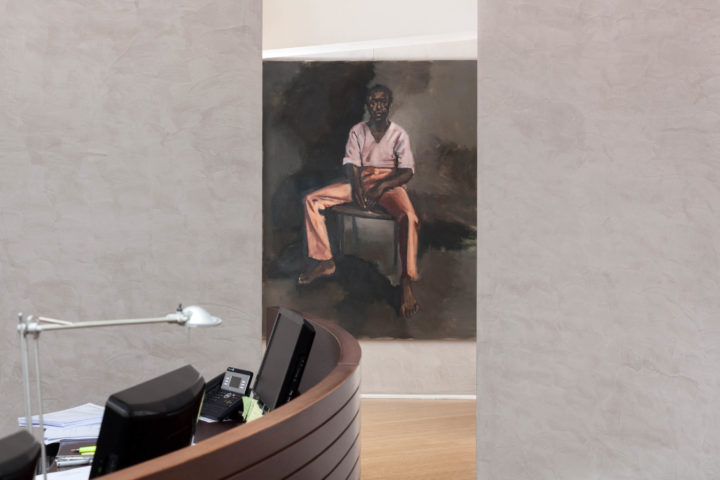

GI: No, not very long, since 2015. We’re on our third exhibition now. Davide Monaldi and Luca De Leva were the first two, and now Andrea Romano. I already have two of his works. I really love his expressive language, the marked contrast in his work between fragility and hardness, and particularly the ambiguity and innovation with which he approaches a classic medium like pencil drawing. He’s an extraordinary portraitist but his works go well beyond formal beauty. This aspect is evident throughout his project at my firm: more than figuration in itself, the artist is interested in the subjects he chooses, their physiognomy or their character, and the way in which he depicts them. He chooses to work the marble that “encloses” the pieces — presented at my firm for the first time — with his own hands. That emphasizes all the more the sense of alienation you often get from forms and materials that simultaneously attract and repel each other, which is characteristic of his work.

GG: How do you see the future of the collection?

GI: I hope to always have the strength to keep going forward. Right now I have various projects in development, for both the 1930s collection and the contemporary one. And for me, in a certain sense, it’s a single collection. My dream is to create an exhibition that stages a confrontation between the blood of Scipione and the blood of Qureshi, to show that the human soul is always the same.