Manifesto, Julian Rosefeldt’s film project that aspires to historical grandeur, landed in Buenos Aires as an overconstructed exhibition at Fundación Proa. Three rooms host twelve films starring Cate Blanchett, who performs a kind of textual survey of the twentieth-century avant-garde.

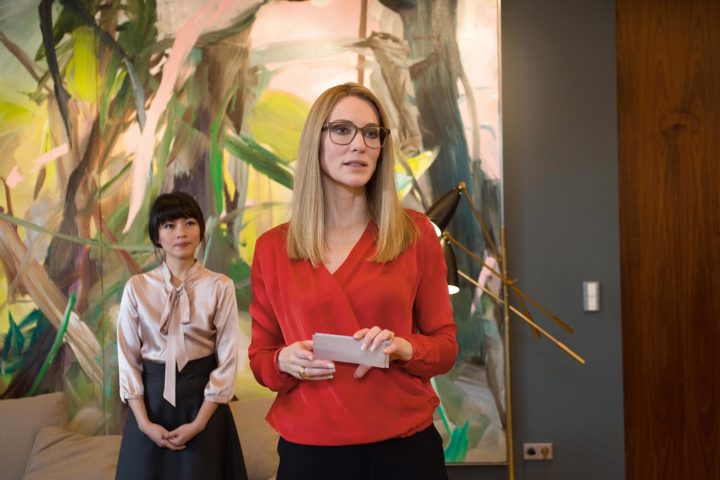

The actor, playing such diverse characters as a firm’s CEO, a news reporter and a stockbroker, recites the seminal texts of various art movements. The screenplay allows for small affinities in the coupling of character and text: Marinetti’s accelerationist emphasis and a financial employee; the Russian avant-garde and a scientist who finds, in a research complex, a black rectangular object. For the texts of Bruno Taut, Antonio Sant’Elia and Robert Venturi, Blanchett is a worker in a trash-incinerating facility, hinting at relationships between architecture, economic growth and environmental sustainability. With remarkable precision, the actor brings an emotional range to disparate artistic ideas, conveying in turn authority (a fancy choreographer), warmth (a first-grade teacher) and exaltation (a young punk lady in a bar).

Character development, nevertheless, gives way to synchronized lecturing via the primerisimo plano of Blanchett’s face and her simultaneous reciting, on all the screens, of discourses that can have an authoritarian undertone. This climatic synchronization shifts the viewer’s attention from the individual films to what occurs in the entirety of the room.

It’s a bit off-putting that Proa’s show doesn’t end with Rosefeldt’s work. A subtle pedagogical quality is already embedded in the virtues of Manifesto (the viewer, in a specific moment, confronts six of Blanchett’s giant faces reciting texts fundamental to the Western art canon) but, in addition to the films, the institution filled an extra floor with information (photos and texts) further explaining the characters, their manifestos and, more generally, what the avant-gardes of the past century were. It is a gesture more akin to the anti-avant-garde wooden donkey Bertold Brecht kept on his desktop with the famous lemma: “Even I must understand it.” Or at least, be lectured.