The paneled double doors of the neo-classical mansion-cum-gallery open onto a dark curtain, beyond which seems to lay great promise; the draped velour entices the viewer (over an unfortunate, shin-high black step) into a world populated by projectors and their compatriot screens.

Kahlil Joseph’s varied audiovisual works to date, from a haunting black-and-white video for FKA twigs, Video Girl (2014), to a dark commercial for a Maldives resort, The Mirror Between Us (2013), have revealed a heterogeneity and signature poignancy. Although it’s exciting that Joseph is exhibiting in Athens, it seems a world away from his primary foci (often Los Angeles, usually black culture).

This exhibition, a slow-motion meditation on mortality with a hip-hop backing track, immediately raises questions about the nature of video in the gallery context. One of the three works on view, Until the Quiet Comes (2012), ostensibly a music video for the songs from the album of the same name by fellow Californian and similarly necro-obsessed electronic producer Flying Lotus, has been viewed online several million times. Here it is displayed on loop without an obvious beginning or end point. Portraying the journey to the afterlife of two recently deceased Angelenos, through abstract dance moves (played in reverse) and creeping lowriders, its unsettling atmosphere successfully elicits a feeling of terror for The End. Its stuttering soundtrack, however, was unfortunately audible over the dual-screen projection of Nooksie & Janet (2016) in an adjacent room. The latter video, continuing Joseph’s collaboration with FlyLo, utilizes a more ambient sound palette to bathe lingering images of well-dressed children amid the prolonged tension of an Oklahoma rodeo. It makes for a melancholy seven-minute short, though one here somewhat interrupted by the inadequate auditory presentation.

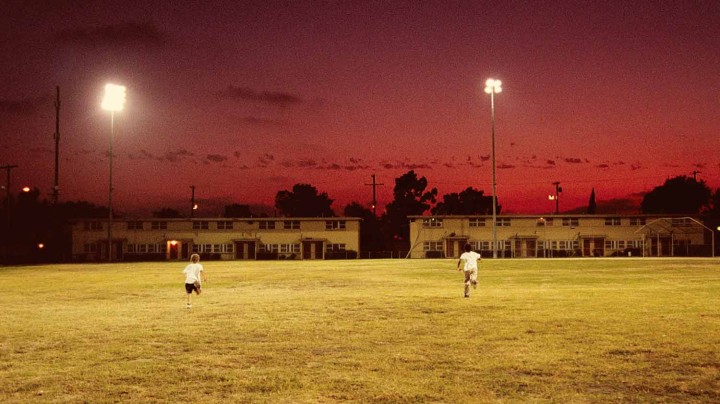

m.A.A.d. (2014), originally conceived as the backing tour visuals for hip-hop artist Kendrick Lamar, comprises a series of affecting slow pans. Portraits of downtrodden figures, set to Lamar’s vocal “Promise that you will sing about me… when the lights shut off and it’s my turn to settle down”; a shot of a lone tissue box on a bench in a funeral home; and faceless characters hanging like predatory bats from lampposts and shop fronts, are all difficult viewing, notwithstanding their rootedness in both Lamar and Joseph’s lives.

Despite being decontextualized from their origins on laptop screens and gig venues, and their transposition from small screens to the sometimes-awkward formality of the gallery, these short works remain successful contemplations on the fragility of life, and they cement Joseph’s standing as a master of the subtly distressing.