American artist Cory Arcangel talks with Flash Art about his technological exploration of obsession, obsolescence and the vernacular.

What’s the #CurrentMood?

How do I even answer that? Maybe #CelebritiesOnDrugs?

At Lisson Gallery in London you recently showed a selection of wall-based works, presented in the same format, in carpeted rooms together with a new audio piece. Can you tell me how the exhibition originated?

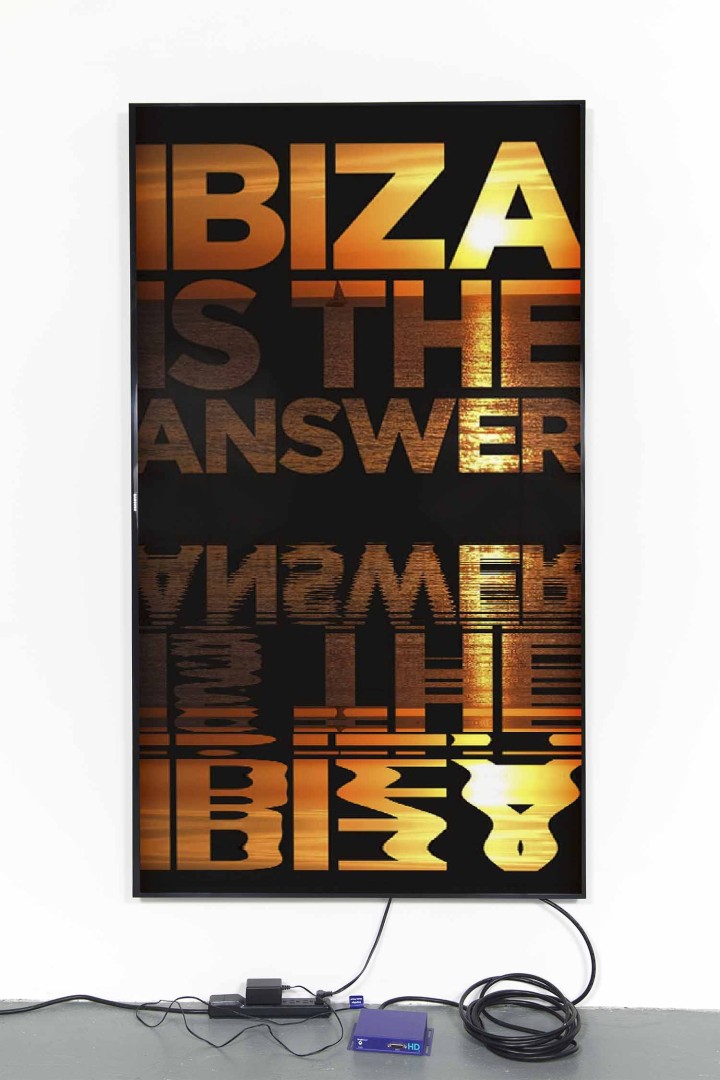

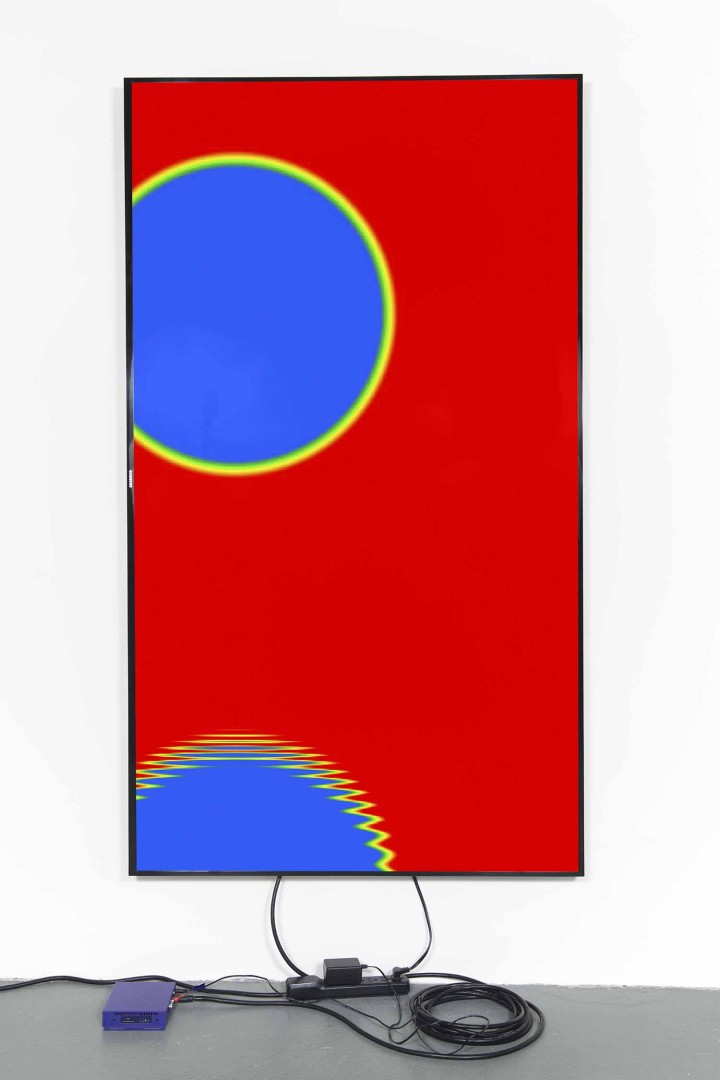

I’m a digital pack rat. I have every file I made or downloaded off the Internet since I was a teen. And a couple of years ago I finally collected everything — about 750,000 files — in once place. This show came out of that process. More specifically, it came from clicking around in all that stuff. So in the show there are tons of different series I have been working on over the last ten years — “Scanner Paintings,” “Photoshop Gradient Demonstrations,” and “Lakes” — as well as things which were on my drives but not exactly “art” — things like old cell phone photos and random images I downloaded off the net.

Several elements in the exhibition either reactivate existing material or appropriate it for a different purpose. How do you see the notion of the archive in relation to reworking visual imagery you produced and collected over all these years?

I can just talk specifics, as I am sitting here in front of my computer. My archive is literally a twenty-four-terabyte hard drive, and it is fairly organized. I am able to see all the different works I made since the 1990s, and all the research that went into them. When making the show, pretty easily, in an hour or two, I was able to pull up thousands of images and put them into a folder. I started off with a thousand or more images and then I narrowed it down to five hundred, then I narrowed that down to two hundred, then one hundred, then fifty, then thirty and then twenty. Then I made some new things depending on the twenty.

It’s kind of as if I turned my hard drive upside down, dumped everything on the floor, and sifted through the pile until I came up with twenty things I felt represented something.

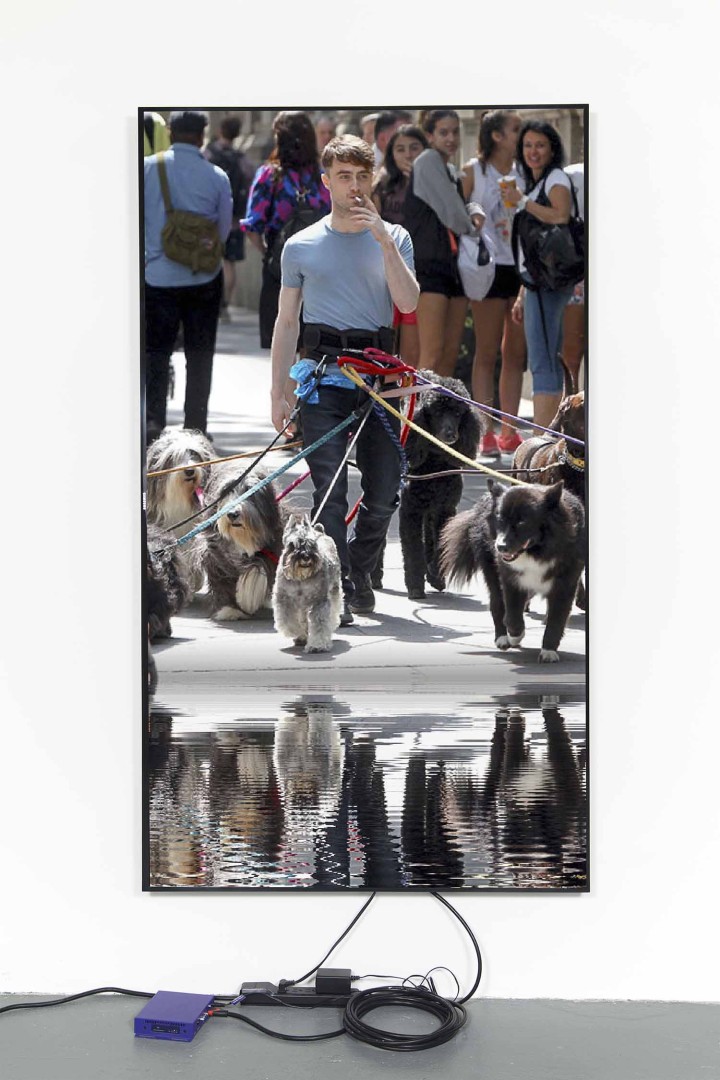

Some of these images relate back to the clickbait campaign you are running alongside the exhibition. What would you say is your relationship to the vernacular?

It’s about shifting context. By taking images from the show and running them in a clickbait campaign — the really trashy articles that you often see at the end of articles on some websites — it’s just playing around with Lisson, dispersion and context. Is an image more important on the wall of Lisson than next to celebrity trash online? Can it resonate in both spaces? Questions like this.

Your work is often discussed in relation to the obsolescence of technology. I am interested in the way you are appropriating your own work and translating it into an upgraded technological output. I think it’s a very ingenious way of keeping it relevant.

It keeps the work alive. In the show, there is a work from 2005, Mig 29 Soviet Fighter Plane, Clouds, originally a Nintendo game hack, which is now running on a Nintendo emulator on a Macintosh OSX desktop with some other Macintosh programs. It’s quite modern looking. I understand the original work is historically relevant, but it’s important to me to give it some energy and to keep it floating around. Not to mention it’s so easy to pull this stuff off my hard drive and play around with it.

I have been following your work over the years and I’m fascinated by how the context in which you are operating has changed dramatically.

I wouldn’t have been able to do an exhibition like “currentmood” at Lisson ten years ago. I wouldn’t have had the knowledge, and I wouldn’t have had the nerve and it wouldn’t have made sense — which is a lot to do with the context. It would have been completely impossible to understand. When I first showed the “Photoshop Gradient Demonstrations” in 2006–07, people had no way to read that, and when I first showed the Nintendo stuff in galleries, again people had trouble reading it.

I have been thinking about the diagram that Guthrie Lonegan made, “Hacking vs. Defaults,” in relation to your “Photoshop Gradient Demonstrations” series in which you relinquish any knowledge about digital technology by using a default mode.

Guthrie is one of my favorite artists of all time! At a certain point vernacular use of technology was absolutely not a part of my work. Though, it was around 2000, when I first saw Paper Rad’s website, that my thoughts on all that changed. Paper Rad’s website was the first convincing work I saw that dealt with vernacular technology – armature homepages, low rez flash animations, and stuff like that. That site was a masterpiece. I would definitely credit them for opening up that part of my work. And it was through collaborating with them that my work started to move away from coding. Guthrie’s chart is very good in the way it divides those two ways of thinking about technology, which I think is split on a generational line.

Your work is particularly relevant today because it came from within a context of early digital art but it crosses over into post-Internet. I think many younger artists see your work as a point of reference. How do you see that?

The post-Internet question! That word gets used a lot, and everyone has a different meaning for it so it’s hard to talk about it. When I was in school in the late ’90s, art students hated computers. If you were on a computer, you were not making art, and art that did use computers was called “media art” and was seen as techy. I think what happened was, a few generations later, you had kids who were in art school when computers finally became okay, and they graduated and started doing shows.

What would you say it means to be a media artist today?

I think the way that I use the term is old-fashioned — to denote an artist who makes medium-specific, experimental electronic work. There have to be new words because everything has changed, you know? I am clearly tied to early digital work, when there was a clear division between digital and fine art. Things didn’t cross back and forth, and I still consider myself part of that earlier era even though my work ended up crossing over. Even my Lisson show is split down the middle between wall works and real-time software performances. But I don’t know what it means to be a media artist today.