While state-run art institutions in Russia experience uncertain times due to funding cuts and the dismantling of existing infrastructures, the fifth Moscow International Biennale for Young Art opened in all its glory, reflecting a reshuffling of the ruling elite.

The main show features almost ninety artists from more than thirty countries, but the number of participants in collateral events scattered all around the city is practically uncountable. There is the sense that the whole of Moscow, like the town of Gatlin in Children of the Corn, has been occupied by youth. The “reverse ageism” of this edition has reached a parricidal peak: not only is “young art” exclusively promoted, but curators, commissioners and designers were also hired based on their biological age (they must be under thirty-five). It also differs from previous Biennales in that the two so-called “strategic projects” that accompany the main exhibition are tailored by foreign curators. Although they foster little dialogue with the local art scene, these three components successfully showcase three popular philosophical approaches to art making and curating.

With its manifesto-like tone, curator Joao Laia’s “Hyperconnected” refers both to object-oriented ontology and theories of the Anthropocene as two ways of decentralizing the primacy of human subjectivity. Proposing a conflation of culture with nature, it also privileges relations over entities — something that modern philosophy since Descartes has strongly rejected. Colorful, bright and kitschy, this exhibition stuffs all four floors of MMOMA at Ermolaevsky Lane with different hybrids and assemblages in which the digital becomes coextensive with the natural. Neringa Černiauskaitė (aka Pakui Hardware)’s eccentric structures give these ideas a proper aesthetic expression: she puts anthropomorphic elements onto rolls of real lawn, adding LED lamps, epoxy, food dyes and microcontrollers. In somato-, techno- or biocapitalism the body is no longer integral, but is fragmented and penetrated by new technologies that, in Preciado’s parlance, are “soft, featherweight, viscous, gelatinous.” However, such a flat ontology as proposed by Laia, in which causal relations become wanton and promiscuous, undoes the idiosyncrasy of the arrangement. Proposing attitudes rather than subject matter, and echoing the last Documenta, it does not subsume them under an authorial voice.

By contrast, “Time of Reasonable Doubts” (curated by Silvia Franceschini with Valeria Mancinelli at NCCA) remains within continental tradition — its very title alludes to Cartesian skepticism. One could say the whole show spatializes “the transcendentals,” rendering them palpable and solid. Following in the tradition of Foucault, it imposes the Kantian notion of “conditions of possibility” onto the field of discourse and knowledge, foregrounding the way perception is structured by “the protocols that govern the present moment.” Compared to the more loose and open-ended “Hyperconnected,” this austere and rigorous show prefers traditional mediums, achromatic colors and endless texts. Selected artworks interrogate documents and fictions in all possible ways: juxtaposing original and remake (Urok Shirhan’s Remake of Paul Chan’s “Baghdad in No Particular Order”, 2012); erasing faces and personalities (Basma Alsharif’s The Story of Milk and Honey, 2011); or applying photo-etching techniques onto digital images (Mikhail Tolmachev, Line of Site, 2015). But a generally sterile and highly aestheticized atmosphere negates the political acuteness of the latter piece, which is perhaps the only one in the whole Biennale that tackles issues around hybrid warfare in Ukraine.

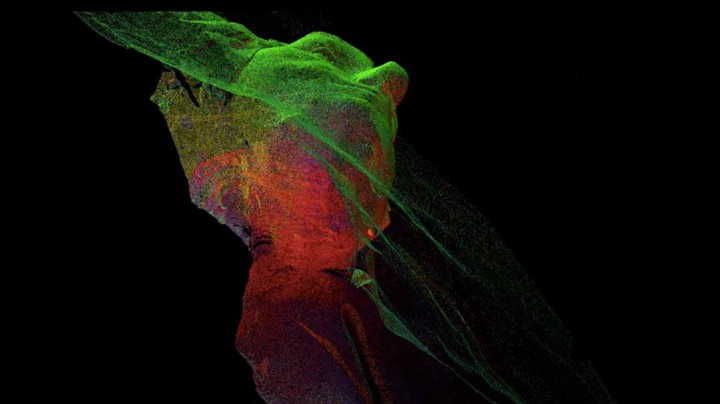

The main project, “Deep Inside,” curated by Nadim Samman from an open call for entries, is situated somewhere in between these two antithetical approaches. With all his eloquence, Samman speaks of the same problems that were raised by Laia — namely how today’s discrete entities and fixed borders are being penetrated — but with anthropomorphic lenses discarded. At the same time, he goes back on his words, emphasizing that scientific knowledge allows new forms of “deep” control that may manipulate what until now remained untouchable. Nevertheless, this new political regime, like Franceschini and Mancinelli’s project, contains fractures that artists can occupy and actualize through different modes of resistance. To emphasize his statement, this huge blockbuster exhibition finds spatial analogies within the interiors of Trekhgornaya Manufaktura. For instance, Alvaro Urbano pierces a hole in a wall (Untitled, 2015) that opens onto a fictional landscape, while Rustan Söderling’s film Eternal September (2015), with its quasi-Tarkovskian manner, drowns in the darkness of deindustrialized chambers. Still, despite reflecting new modes of surveillance, synthetic technologies and data trajectories, none of the works take into account the disposition of power that lies right on the surface.

Trekhgornaya Manufaktura, the textile factory that played an important role in the 1905 Revolution, was recently bought by oligarch Oleg Deripaska and then violently purged of its workers and tenants. By hosting an international biennial, it hopes to attract potential developers and renters to make another creative cluster of young cultural prosumers. Of course, this lack of dialogue with the local context is not a drawback of any of the shows in particular, which, one must admit, differ advantageously from previous editions; it is, however, a structural problem with the “Young Biennale” itself, which since its inception has been more about networking, self-presentation and CV development.