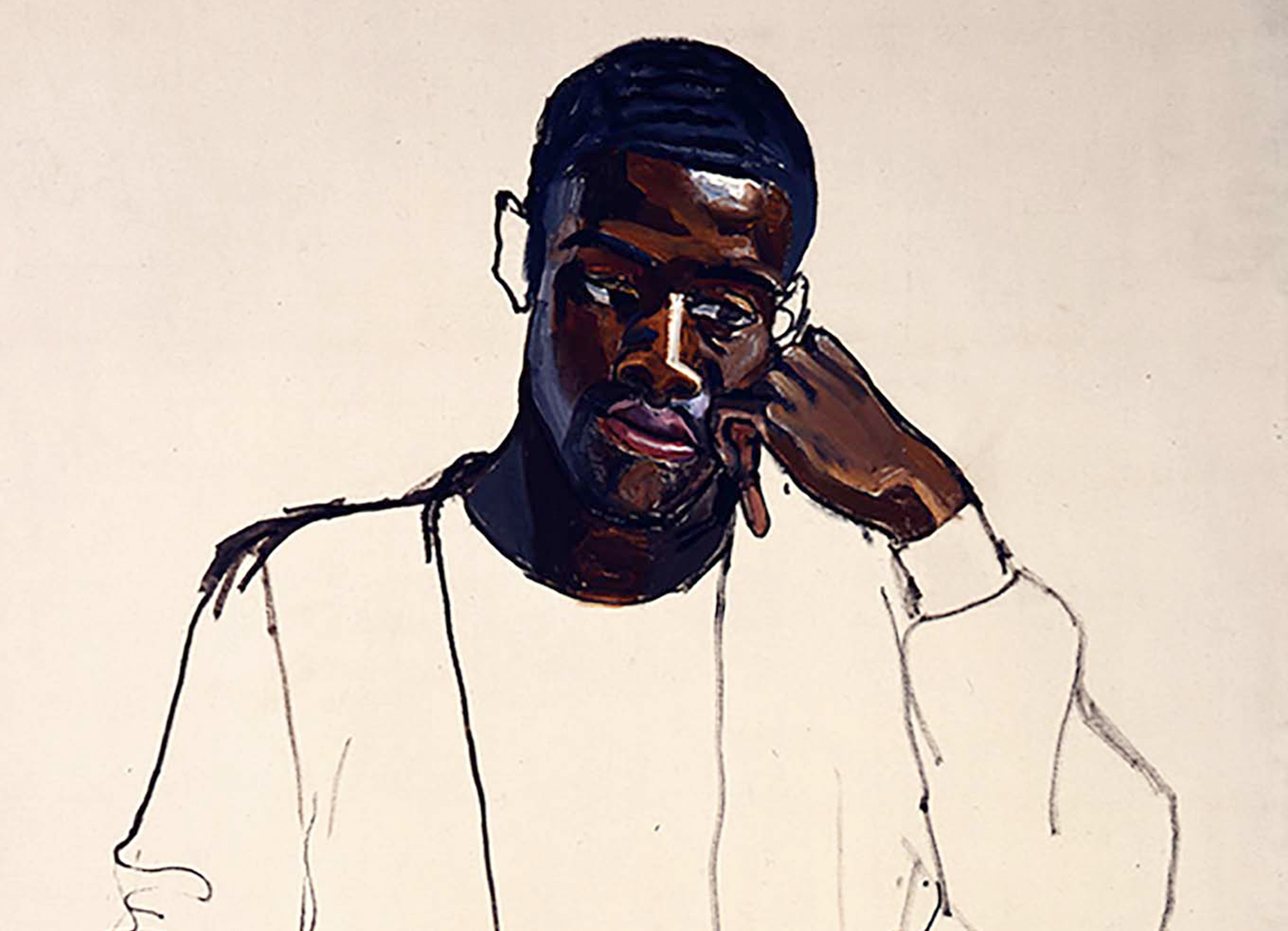

In his first exhibition at Galerie Perrotin, New York, Japanese artist Izumi Kato presented a series of paintings along with several sculptures. The sculptures — bulbous-headed figures, waif-like bodies with wide, staring eyes — almost mirror the paintings, portraying characters from an unspoken narrative, as if they have just stepped out of the two-dimensional surfaces.

There is something very human, if also otherworldly, about Kato’s work — a sense that the artist has merged his dreams, fantasies and personal life into a visual reality that he has inhabited for years. An element of obsession dominates the work; his fragile figures stand, individually or in pairs, in darkened landscapes. Has a thin layer of transparent skin been peeled away to reveal strata of muscles, veins and brain matter? There is no recognizable likeness in the figures, despite the familiar features that make up faces (eyes, nose, mouth) and bodies (torso, arms, legs). They could almost be considered abstract were it not for our own associations and identifications when looking at these bizarre bodies. The figures speak to a mystical reality, existing somewhere between pleasant dream state and nightmare.

There seems to be a highly psychological element to the figures and the darkness of the landscapes. Are the works informed by dreams or the subconscious?

Whoever makes paintings, his or her subconscious comes through. So that is first. I am, however, very conscious of my color palette and compositional choices with the intention to be evocative.

The first floor of Galerie Perrotin is filled with paintings, but also features two freestanding sculptures. Can you talk about the sculptural process in relation to your painting?

I am a painter first and foremost, and I have worked this way for some time. Eventually I wanted to refresh [my practice] and first started making carved, wooden sculptures using the same type of wood that is used to make traditional Buddhist statues. Then I was introduced to vinyl through a friend who owns a company in Japan that specializes in making toys, such as the Power Rangers. It’s not a traditional material, but for Japanese children from our generation, it is quite familiar because of the toys we played with. There are two molds: one for the upper head and neck as well as a mold for the body. The factory that makes the vinyl sculptures also makes Kewpie dolls. Once the mold is made, everything is painted by hand.

Your work seems to have an African influence as well, specifically African masks. Can you speak on that?

I look at African sculptures, Venus sculptures and toys in Japan from the viewpoint of one even plane and choose not to differentiate. I grew up in a rural town in Japan outside of Tokyo where they believe that everything — even objects like rocks and wood — contains a spirit.

Knowing this, do people from your hometown appreciate your work or find it problematic due to the spiritual nature of the materials you are using?

Since it is the countryside of Japan, where my artwork is concerned, the local people have told me, “We don’t understand contemporary art,” which is typical.