“I keep nothing clean,” Albert Oehlen has said. That’s an understatement. The German painter’s 1988 move to abstraction, a transition incubated in an Andalusian retreat shared with friend and collaborator Martin Kippenberger, catapulted him into the muck — of degenerated fragments of figuration, bruisey hues, garish advertisements and other “selected abominations” — in which he has been happily swimming ever since.

Oehlen’s first New York museum exhibition reveals his perversely systematic approach to abstraction through twenty-seven works suspended between improvisation and deliberation. They are at once fluid and frozen, earnest and ridiculous.

Spread over two floors of the New Museum, “Home and Garden” takes a cue from the artist in eschewing a neat organizing principle — the chronological — in favor of something more chaotic: juxtaposition within and among groups of paintings, gathered under a title that nods to shelter magazines and sales circulars while preserving the tension of inside versus outside. The contrasts commence with two massive monochromes yoked by their daubed and smudged grays: Interior (1998) and Bad (2003), the former refusing pictorial representation while the latter frustrates its seeking with morsels of portraiture and a zeppelin-like bathtub floating atop crude, extruded claw feet.

The surrounding canvases span nearly three decades, from early self-portraits (and an underwhelming 2005 installation piece that tucks a portrait of the artist into a tiny bed) and roiling abstracts that find Oehlen experimenting with density and testing the limits of hues sordid and saturated to two explosive works, both from 2009–11, rooted in pasted advertisements. Borrowed from billboards, the collaged elements flicker through Oehlen’s signature haze of brushwork, rag-blurred plumes and finger-painted gestures that evoke a sky mottled by the dregs of a fireworks display.

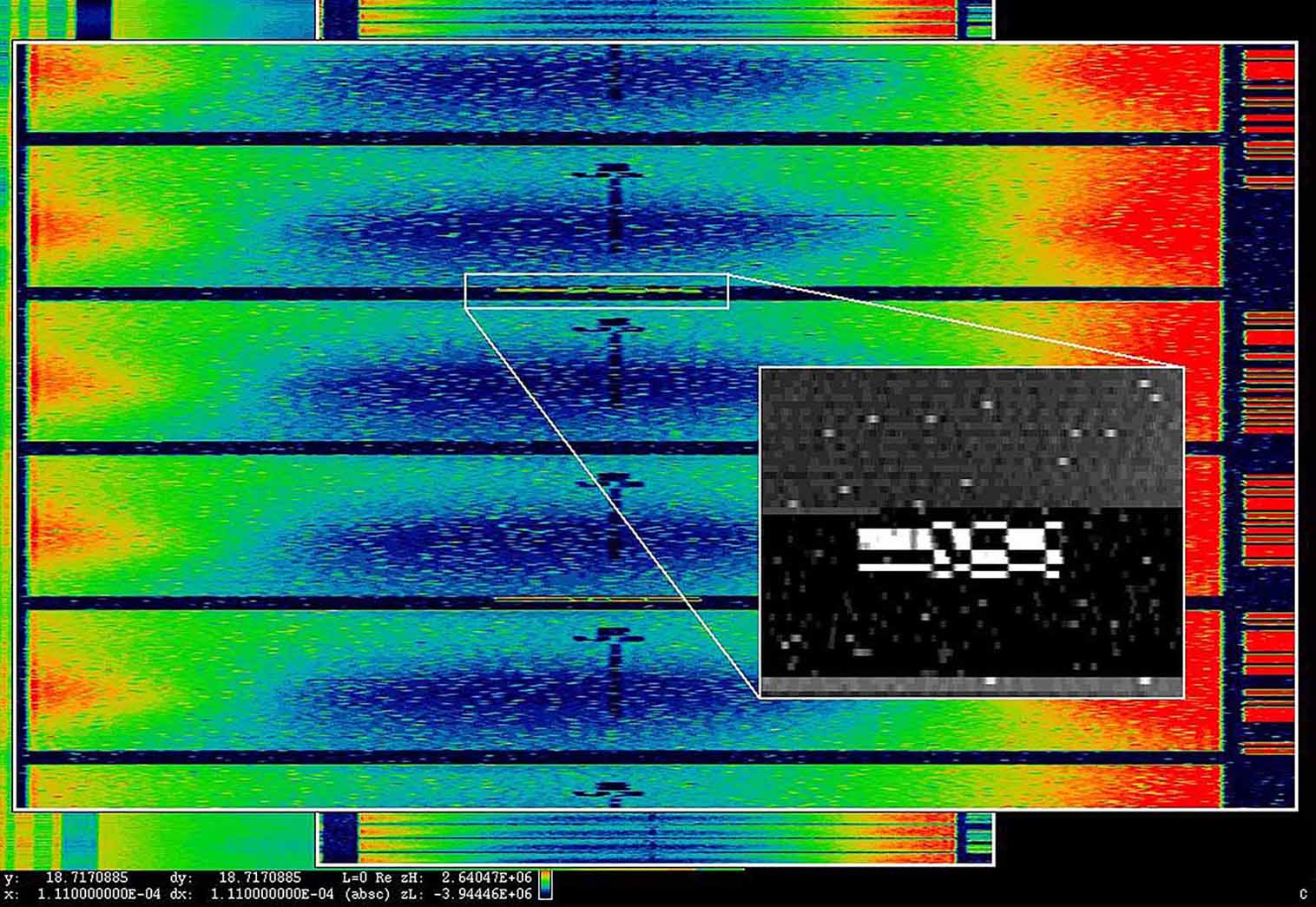

At the center of the exhibition are five of Oehlen’s “computer paintings,” a series initiated in the early 1990s that evolved into the brightly colored “Switch” paintings that get a floor to themselves. Combining pixelated thickets with snaking painted marks, the black-and-white works succeed in eliciting Gustonian levels of repulsion in anyone who dabbled in clunky precursors to MS Paint. They are deliberately awkward creations made with dumbly precise tools, and by masking the limits and practical rules that Oehlen imposes on his work, these lo-fidelity all-over paintings are invitations to leave behind the world of right angles and three dimensions and to get down and dirty in the electric mud.